The Man in My Basement: Capturing a Psychological Unraveling

Cinematographer Ula Pontikos, BSC details her visual strategy to transform this thriller's main setting into a metaphor for mental deterioration.

When director Nadia Latif first approached me to shoot The Man in My Basement, her adaptation of Walter Mosley's acclaimed 2004 novel, I knew I was in for a captivating ride. Nadia had written a powerful script based on the book, and the task of translating this psychological drama to the screen immediately compelled me. The story centers on Charles Blakey (Corey Hawkins), an African-American man stagnating in a personal and financial rut, who decides to allow a strange white businessman, Anniston Bennet (Willem Dafoe), to rent out the basement of his home for the summer. Charles’ anchor, and his burden, is the large house he can no longer afford — a structure that functions as a metaphor for his own personal wounds.

From the outset, we worked with our incredible production designer, Kathrin Eder, to design Charles' house as a character, and a representation of his psyche. Kathrin’s attention to detail imbued the space with a sense of faded grandeur and a slow decay creeping in every corner; her approach created an environment in which every floorboard and strip of peeling paint effectively conveyed a legacy in ruin. We also collaborated closely with composer Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe, whose work helped translate this visual decay into a haunting soundscape, in our efforts to make the set "breathe."

Consequently, my use of light and color was never incidental; these elements were designed as psychological cues. The sickly sodium glow of street lamps, for instance, washes over the frame whenever Charles' paranoia or shame surfaces, as if the outside world is violently echoing his inner turmoil.

Throughout the film, we built an emotional palette for Charles' journey: the cold cyan of nightmare sequences, the green-tinged unease of gas stations and bank lobbies, and persistent sodium vapor — all building toward a violent climax steeped in red. Color, in this way, became the visual language of his memories, fears and unraveling sense of self, as well as the burden he carries within him.

This is the challenge of an adaptation. Whereas a writer can devote chapters to develop a character's interiority, the filmmaker’s job is to build that emotional authenticity into the very space the character inhabits. We must manufacture the atmosphere that generates that interiority, using light, color and space to make the audience feel what the character feels without a single word of explanation.

In a scene in which Charles runs home from a party, our heightening of the character's perception and sense of overwhelm reaches an inflection point. Here, the line between his drunken point of view and his terrifying reality — that Anniston’s presence has now become a wholly oppressive force — is dissolved. The scene is saturated in an orange hue — a color that feels at once warm and sickly, intimate and threatening. This dissonant orange becomes the light of his paranoia; we aimed to immerse the audience in his subjective, unraveling state, and to highlight his feelings of fear, isolation and disorientation.

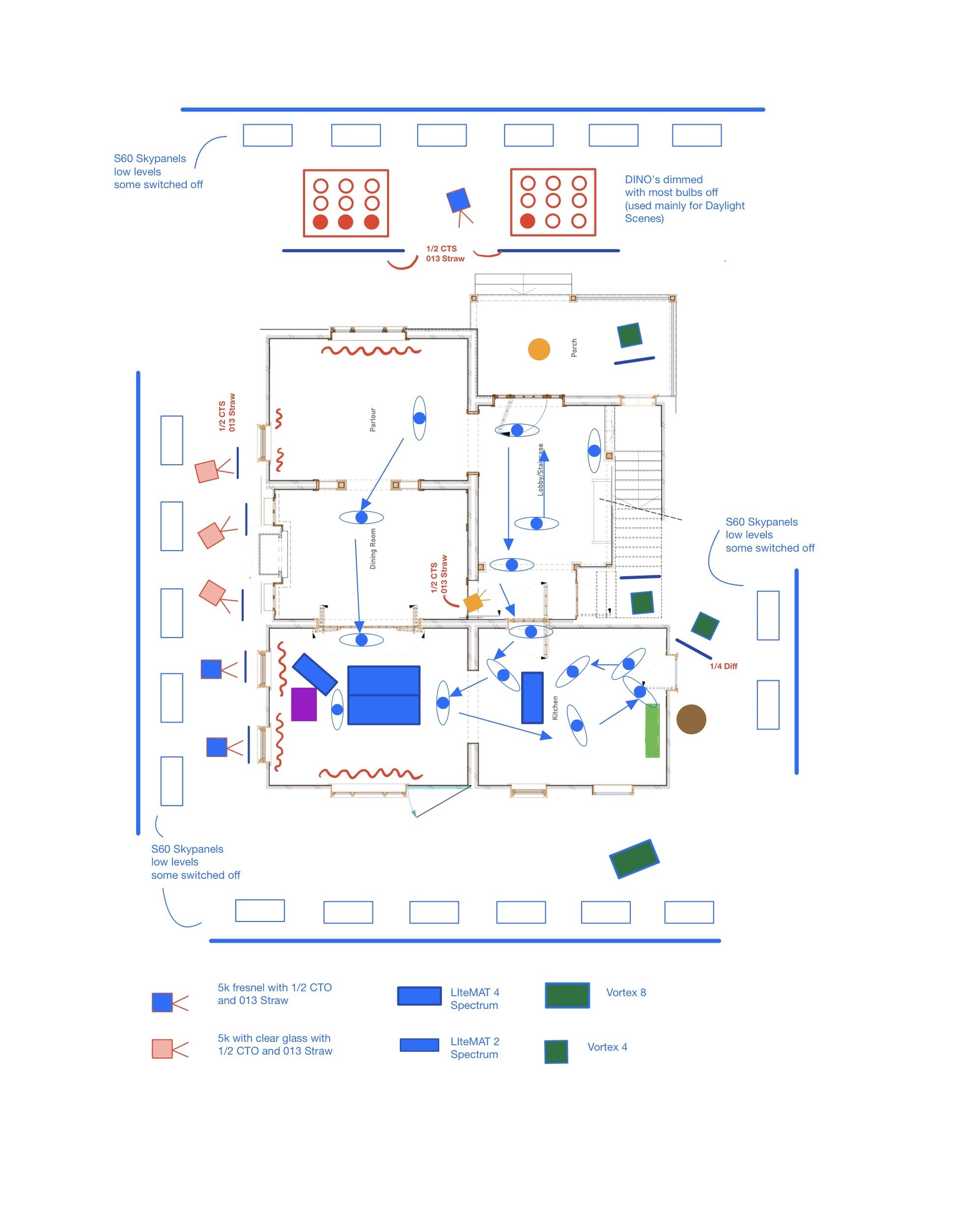

The scene presented some unique challenges. Our house set was built on a stage at Dragon Studio in Wales and would include a number of shots in which its front door would be open, and we needed to make the nighttime woodlands visible through the open door. We also had to light the whole house as one continuous set, with the lighting building up to a crescendo of strobes. (See our lighting plan in the diagram and corresponding key below.)

To establish the street lighting outside of Charles' house, gaffer Peter Chester and I sourced real sodium-vapor lights, which were mounted on nearby trees. The street outside the house set was given its own practical lighting as part of the set design. We wanted the space to feel sickly and exaggerated; to achieve this, we positioned our sodium-vapor lights off in the distance, which allowed them to later serve as our main lighting source for moments in which Charles is alone inside the house.

We leaned into chiaroscuro, motivated by a single, dissonant orange light source. This helped carve Charles out of the darkness, sculpting his fear with sharp light and deeper shadows and making the environment itself feel as sickly and threatening as his paranoia.

To make the light harsh and create shapes on the walls and floor, we used 5K Tungsten lights with clear glass; Kathrin also sourced beautiful fabrics, which further enabled us to create patterns on the walls. To match the light color of our sodium-vapor exterior, I used Lee's 1/2 CTO Lighting Gel Sheet and 013 Straw Tint filter.

To help blend our stage-built house with the exterior world as seamlessly as possible, we employed a strategic two-shot approach for our open-door sequence. The first shot is a POV shot from Charles' perspective, filmed on location to capture the authentic, immersive texture of the night. The second shot is a wider master shot from inside the house, which required the use of greenscreen; this allowed us to carefully composite the interior set with a background plate of the woodland, which was shot on location to ensure visual continuity.

Our overarching goal was to make the house set feel like a real location, and this was especially important for all of our scenes in which characters converse through the house's open door. It was a fun and rewarding challenge to minimize our use of greenscreen and composite plates and strive for in-camera authenticity whenever possible. In fact, only about one or two shots of the basement and one from our POV sequence made use of greenscreen.

Perhaps more than for any other reason, our entire house set was designed to serve the choreography of what we'll call "the television moment." In this moment, the action of the story unfolds as part of a continuous thread of mounting tension: Charles enters the living room, switches on the television, hears a noise and subsequently discovers that his basement door is open. His panic is palpable as he grabs a shovel, surveys the hallway, discovers that the front door has been opened, and moves methodically through the parlor and into the living room, looking to confirm whether or not the house is empty.

The catalyst for this moment of action is the television, which Charles has left on and is flickering as it broadcasts disturbing footage of the Rwandan genocide. Rather than only relying on the TV screen’s glow and composting the footage later in post, we preselected the Rwanda footage and filmed it playing on a CRT TV, to capture all of its screen's inherent imperfections — scan lines, flicker and subtle noise. This approach was crucial, as the images on the TV screen aren't there simply to be watched by Charles, but to give the impression that they are consuming him, and that his psyche is merging with the broadcast's haunting content. This sense of immersion — accentuated by our use of aggressive strobe lighting from Creamsource Vortex8 units and LiteMat Spectrum 4 units mounted to the ceiling — was created to further dissolve the line between his reality and the TV screen's traumatic imagery.

The CRT TV itself never was bright enough to give us our desired exposure, so it was very important that we synced the broadcast footage to our Vortex units to keep the color and flicker in sync. For our intensified strobe section, we hid Vortex8s throughout the downstairs portion of the house set, to give the entire space a chaotic, flickering light that would "chase" Charles up the stairs.

We chose to shoot The Man in My Basement on the Sony Venice 2, which was paired with Panavision H Series lenses. Spherical lenses felt like the right choice to ground the film in a tangible reality, and frankly, we were both eager to move away from the now-ubiquitous anamorphic look that dominates contemporary cinema.

I often mixed and matched lenses to achieve the perfect focal length for the emotional tone of a scene. For many of our intense close-ups, I relied on Arri’s close-focus 21mm Master Prime. Its unique ability to bring the camera extremely close to the actor's face without compromising the image allowed us to create a deeply intimate and sometimes uncomfortably close perspective on Charles. This combination offered us tremendous flexibility with depth of field and, crucially, exceptional close-focus capabilities. Sometimes I kept the lens so close to Corey’s face that I was almost able to touch him.

Cinematography, at its best, is a form of empathy. It’s the art of transforming a character’s emotional state into a landscape the audience can inhabit. Through the palette we built, the shadows we carved and the closeness we achieved with our lenses, we sought to create that empathy for Charles Blakey. This was all achieved through the power of collaboration, with every department working in unison to craft an experience that lingers not just as a memory of a story, but as a feeling — a haunting, visceral echo of a man confronting the ghosts in his own home, and within himself.