Jurassic Park: When Dinosaurs Rule the Box Office

You can't measure the expectations for the film version of Jurassic Park in ordinary terms, because the level of anticipation is way off the charts.

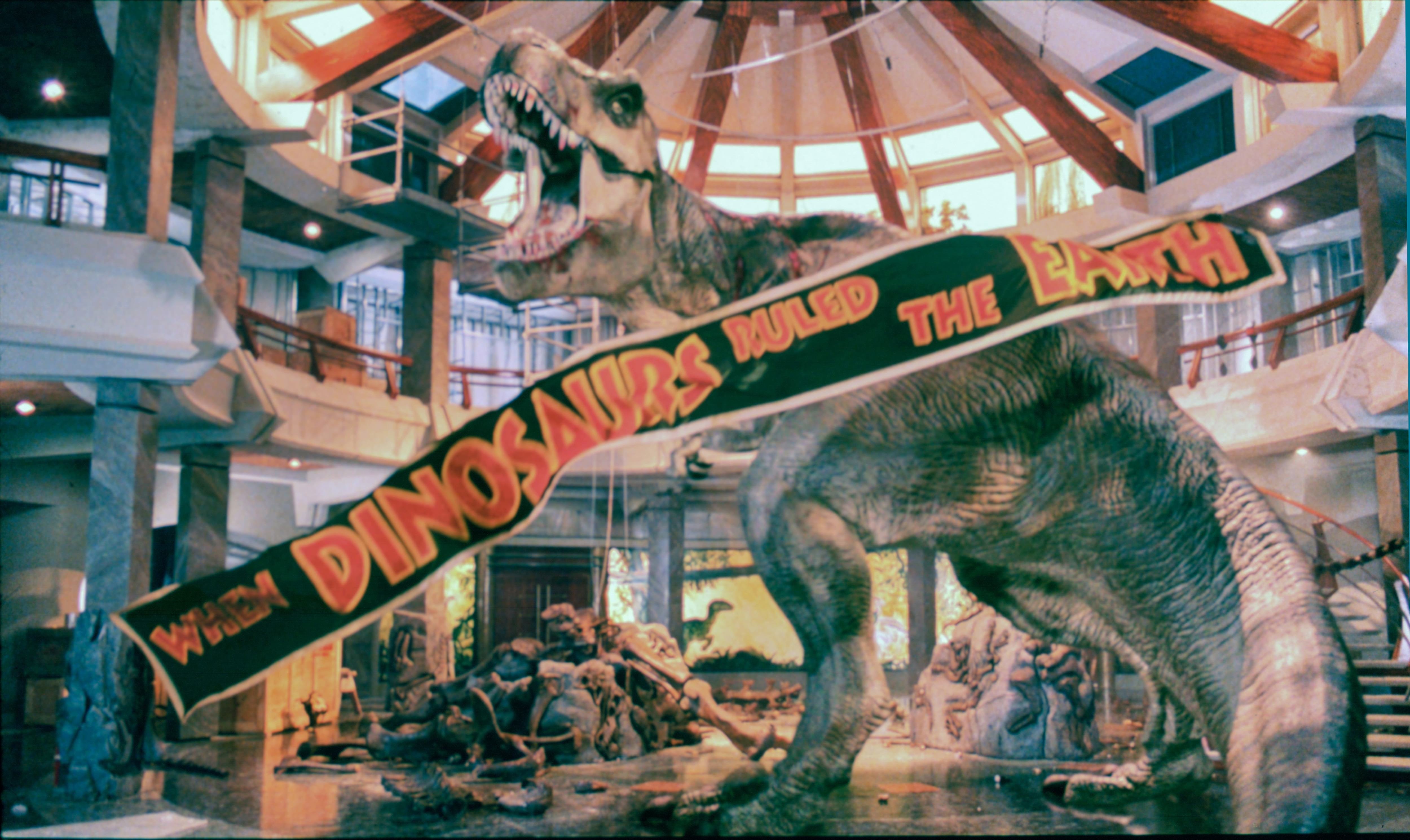

Unit photography by Murray Close

Countless millions of people have read Michael Crichton's bestselling book, in which scientifically created dinosaurs run amok on the grounds of a poorly planned theme park. Three million paperback copies were sold during the last few months alone. Most readers have already seen the movie in the theaters of their minds.

Industry entrepreneurs, meanwhile, are responding to Jurassic Park like a pack of tyrannosaurs tracking their dinner. At last count, more than 140 licenses had been issued to companies planning to merchandise everything from baseball caps and T-shirts to fast food and cereal. Keep in mind that this feeding frenzy took place before one ticket had been sold.

Much of this unrestrained enthusiasm, of course, can be attributed to the public's enduring fascination with prehistoric creatures with tongue-twisting names. Many of us first learned about dinosaurs in preschool picture books. They are typically portrayed as benign, bumbling, downright lovable creatures. One of the most popular contemporary television characters, for example, is a soft and cuddly tyrannosaurus named Barney, portrayed by an actor in a purple dinosaur suit. Most of Barney's fans are two to four years old, and they love him dearly.

But, like humans, dinosaurs came in all varieties, including some particularly vicious carnivores called velociraptors, which, in Crichton's tale, make the worst of Freddie Krueger's nightmares on Elm Street seem like pleasant daydreams. These nasty creatures are particularly well represented in the film.

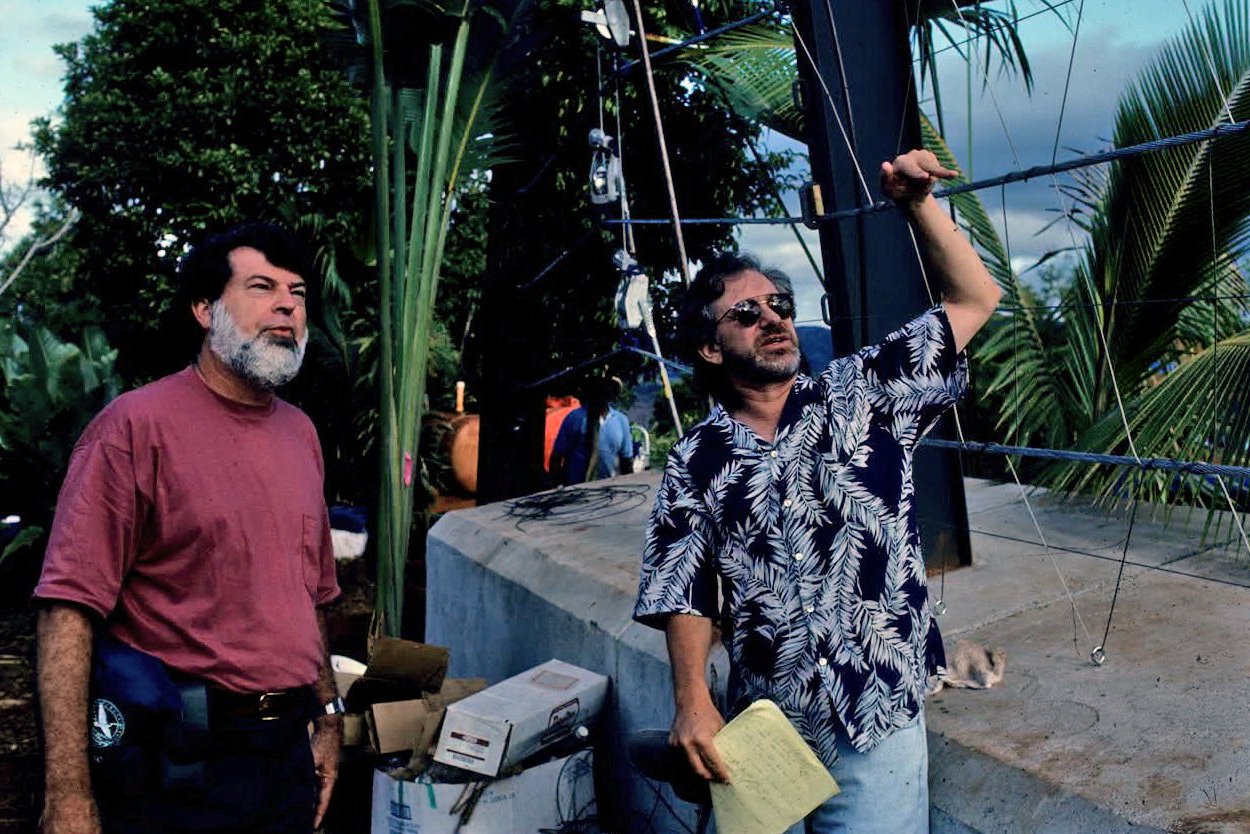

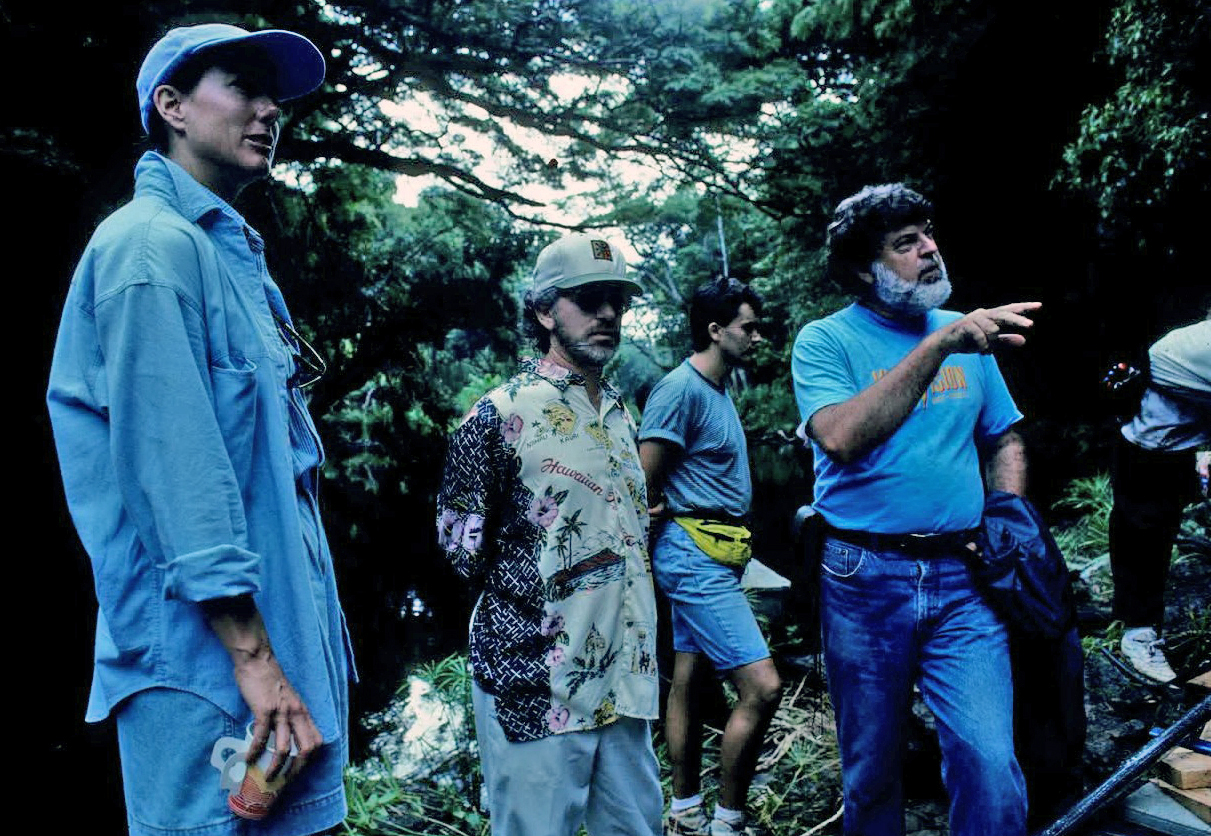

The look of Jurassic Park is in familiar hands. Dean Cundey, ASC had just finished shooting Hook for Steven Spielberg when the director asked if he was interested in translating Crichton's book into the language of film. Cundey had a pretty good idea of what to expect. "Steven was involved with the script for maybe two or three years," he says. "He'd talk about it sometimes while I was shooting Hook. Production designer Rick Carter, with whom I had worked on Back to the Future, was already working on the sets.

“You have to visualize what it would look like if the creatures were there, and plan to shoot the film as though they were actors.”

— Dean Cundey, ASC

“I got interested in what he was doing, the concept paintings and the research. While we were working on Hook, he'd come around with the latest drawings for Steven to look at or approve. I got involved as an observer very early in the project. Steven eventually asked if I wanted to shoot the film after we finished Hook.”

Cundey says that he and Spielberg tried to make the camera into another character in the film. The continuous movement and the choice of interesting and sometimes extreme angles generate a high level of emotional energy. This tactic is naturally intended to keep audience members white-knuckled and gripping the arms of their seats.

Describing a sequence in which the film's characters tour the dinosaur park in a tram, Cundey says, "It's like [the viewers] are along for the ride." People watching the film sway with the visual twists and turns, craning their necks as if they are looking for predators lurking in the shadows.

"This is a signature technique with Steven," Cundey says. "He brings the audience right into a character's face, so they can see what's in his or her eyes. It's a way of developing empathy. The camera is always moving, gradually getting closer to the point of danger."

With Jurassic Park, Crichton, whose other novels-turned-films include The Andromeda Strain and the upcoming Rising Sun, crafted a vivid action-adventure story revolving around the themes of greed and science gone awry. In Crichton's tale, a rich investor builds a theme park set in the Jurassic Age on an island off the coast of Costa Rica. Instead of populating the park with make-believe dinosaurs, he commissions a scientist to clone the real things from DNA samples. In order to test the validity and safety of this experiment, the investor invites a few guests to visit the island before it opens. Naturally, prehistoric mayhem ensues.

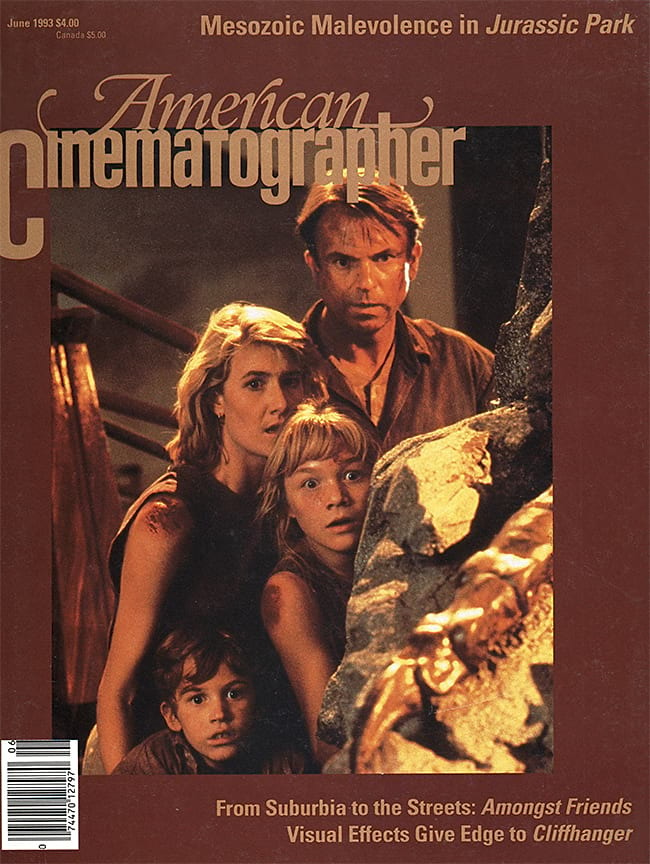

Although Jurassic Park will feature accomplished actors Jeff Goldblum, Sam Neill and Laura Dern (as well as director Richard Attenborough as the island investor), the real stars of the show may well be mechanical puppets and computer-generated-images (CGI). In order for the film to be believable, the digitally created dinosaurs have to blend seamlessly with the live-action footage. As those who have seen the creatures Godzilla, Rodan and Mothra in action can attest, the difference between a snicker and a gasp is slight.

Cundey's phone tends to ring when directors are making bigtime visual effects films. He has already collaborated with Bob Zemeckis on five such films, including Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, the Back to the Future trilogy, and Death Becomes Her. Cundey earned an Oscar nomination for Roger Rabbit, which smoothly integrated a cast of animated characters with live-action film. In Hook, Peter Pan flew with reckless abandon, thanks to the magic of digital compositing and wire removal.

Even with these experiences behind him, Cundey found that Jurassic Park presented a slew of technical questions. How do you light a mechanical puppet so it looks and feels real? How do you make the light falling on the digital creatures look as if it is motivated by believable sources? How does the compositing of digital characters affect the overall mood and texture of lighting, the way the camera moves, and the way images are composed? What about the shadows cast by digital characters?

"You have to visualize what it would look like if the creatures were there, and plan to shoot the film as though they were actors," Cundey says by way of answer. "ILM has done a fabulous job. It's not just wire animation with some texture mapping. They have stretched and squashed the skin. There are moving wrinkles. There are details that you take for granted when you look at something in the real world. All of these things add to the illusion."

Cundey handled the casting of shadows in a variety of ways. Sometimes it was as simple as having a grip hold a flag or a cutout of the right shape in front of a light. These methods took some practice and had to be choreographed like a stage production, with the timing and angles executed perfectly. At other times, shadows were computer-generated and composited digitally.

"We usually made that decision on the spot," he says. "There is a quality to a real shadow that is difficult to replicate in a computer. But sometimes it wasn't possible because of the position and angle of light. So we asked the animators for help."

One of the Hollywood trade dailies recently dubbed Cundey "Hollywood's master effects lensman." He doesn't mind being stereotyped, however; after all, it's happened before. For a while, he was categorized as a specialist in horror films. Then it was comedies. But the truth is that there is a world of difference between Cundey's other visual effects films and Jurassic Park. All of his previous films in the visual effects genre were wrapped in an aura of fantasy. The key to Jurassic Park, on the other hand, is hyper-reality.

"The audience has to believe the unbelievable," says Cundey. "You have to give them as much reality and recognizable truth as you can. They have to walk in the shoes of the characters. They have to feel the terror when the experiment goes wrong and a handful of people isolated on an island become prey for the dinosaurs."

Some of the predators are literally bigger than life, such as the mechanical tyrannosaurus, which towered 18 feet in the air. These oversized props translated into a lot of problem-solving. One important sequence, in which the visual perspective of the actors is simulated in a fairly extreme upwards angle, was shot on a stage. The angle meant that the stage ceiling would be in view. Ideally, Cundey would have simply blacked it out, but doing so would have given him some serious problems with the fire marshal.

"The grip department at Universal came up with some black louvers which we were able to funnel lights through" he says. "When we needed to, we could angle them to create a black background. At night, we opened them up, and that satisfied the requirements of the fire department."

One of the reasons Spielberg opted to shoot Jurassic Park in the Academy standard 1.85:1 aspect ratio, instead of widescreen anamorphic, was to give visual emphasis to the huge size and bulk of the biggest dinosaurs.

"In Hook we had scenes with rows of people," Cundey says. "An anamorphic frame gave us the scope we needed to capture that side to side dimension. In Jurassic Park, you get a better sense of the sheer size of tyrannosaurus rex compared to the people in the 1.85:1 format." The large amount of digital compositing in the film was another convincing reason to stick with the smaller image area.

In addition to his big-budget effects films, there are other frames of reference in Cundey's career for Jurassic Park. Halloween, his breakthrough film with John Carpenter, and Escape from New York are among a series of features he shot during the late 1970s and early '80s which helped define a genre of reality-based horror movies made on shoestring budgets. Those films relied heavily upon the power of the images in evoking emotions in audience members.

It's not a new idea. "I heard it first from James Wong Howe, ASC (Hud) when he was about 70 years old," Cundey recalls. Howe was teaching a class at UCLA while he was preparing to shoot The Molly McGuires. Cundey was a student with a split major in film and architecture. After class, Howe would move to a nearby coffee shop, where he talked with some of the students. "He said as he got older, he learned to simplify by working with less light. I always remembered that when I was being challenged to do more with less. [Low-budget films] taught me to think about how to solve lighting problems without making things more complicated. I learned how to improve a scene by subtracting light, and how I could get two or three shots out of one setup."

That method is apparent in Jurassic Park, where shadows are used to conceal just as light is used to reveal. It's one key to the feeling of anticipation which builds throughout the film. "I think he (Spielberg) used the dinosaurs very wisely," Cundey says. "He shows just little quick pieces of them in the beginning. There is a sense of mystery, and gradually we reveal more and more."

"The idea is to show enough for the audience to understand the moment," Cundey says. "But not so much so that they are sitting there trying to figure out how we did it."

In terms of showing effects, how long is too long? "It's getting longer, because the effects are getting more sophisticated," Cundey points out. "But so is the audience, at least on a subconscious level." In other words, there are no rules that you could put into a textbook with impunity. Success is ultimately based upon the filmmaker's innate instincts.

Cundey is a bit more resolute, though, when he notes that a film's characters are of the utmost importance. If viewers don't care about the characters, they won't care if a few of them become lunch for a hungry velociraptor.

The cameraman further credits his low-budget film days with teaching him that there is more to cinematography than artistry and craftsmanship. He learned how to get along with the cast and how to organize and motivate his crew to give him a little more than they thought they had.

"I don't care what the budget is, if you don't have good chemistry, you can't make a good film," he insists. His camera operator, Ray Stella, SOC, has been with him for 18 years. Others have been on his crew for 15 years, and even the newest people have been working together for seven or eight years.

Jurassic Park represents a logistical triumph. Production stretched over some six months of original photography, mainly on four big soundstages at Universal Studios. The stages were packed with elegantly detailed sets, from the control room at the park to elaborate jungle exteriors.

"We shot many of the jungle night exteriors, visual effects and action sequences on stages, because it was easier to control lighting," Cundey says. The interiors were mainly captured on the 500 ASA Eastman EXR 5296 film. The big daylight exteriors, designed to give the audience a sense of the scope of the park, were filmed on Kauai, which doubled for the island which served as the book's setting.

These exteriors provide an interesting example of how the art and craft of filmmaking converge. In Back to the Future III, Cundey opted to shoot daylight exteriors with the Eastman EXR 50 ASA daylight film. He knew he would be shooting in bright sunlight and he wanted the richest possible imagery, with deeply saturated colors devoid of the slightest hint of grain. In Jurassic Park, however, there are daylight scenes in which the audience gets glimpses of one or more dinosaurs in the background. The latter has to be in sharp focus, because the image of the dinosaur is going to draw the audience's eye to that area of the frame.

Cundey never knew when clouds would float by and block the sun, creating dark shadows. He anticipated shifts in sunlight by using the 100 ASA EXR 5248 film to photograph exteriors, because it gave him the edge he needed to pull a deeper stop, usually within the range of T2.8 to 4.

"Steven likes to storyboard," Cundey says. "It helps organize his thinking." At the same time, Spielberg is an intuitive director who will often modify or throw away the blueprint at the moment of photography. Not this time. "He stuck pretty close to the boards because of the schedule, and because we were going to be doing so much digital compositing."

Cundey shot most of the plates for scenes destined for digital compositing in the VistaVision format, using VistaFlex camera ILM developed for Roger Rabbit. "You usually work with a larger format camera for plate work, because you inevitably lose some image quality as you go through each generation of optical compositing," he says.

"However, since compositing was done digitally at ILM, it gave us the opportunity to try something new. I shot some of the outside exterior plates in 35mm film format using the 5245 film. That saved us some precious time. The image quality was pristine, and the composites made with the 35mm film plates are transparent."

From the beginning, Cundey says, everyone on the project was in touch with the fact that the audience is going to have their eyes on the dinosaurs.

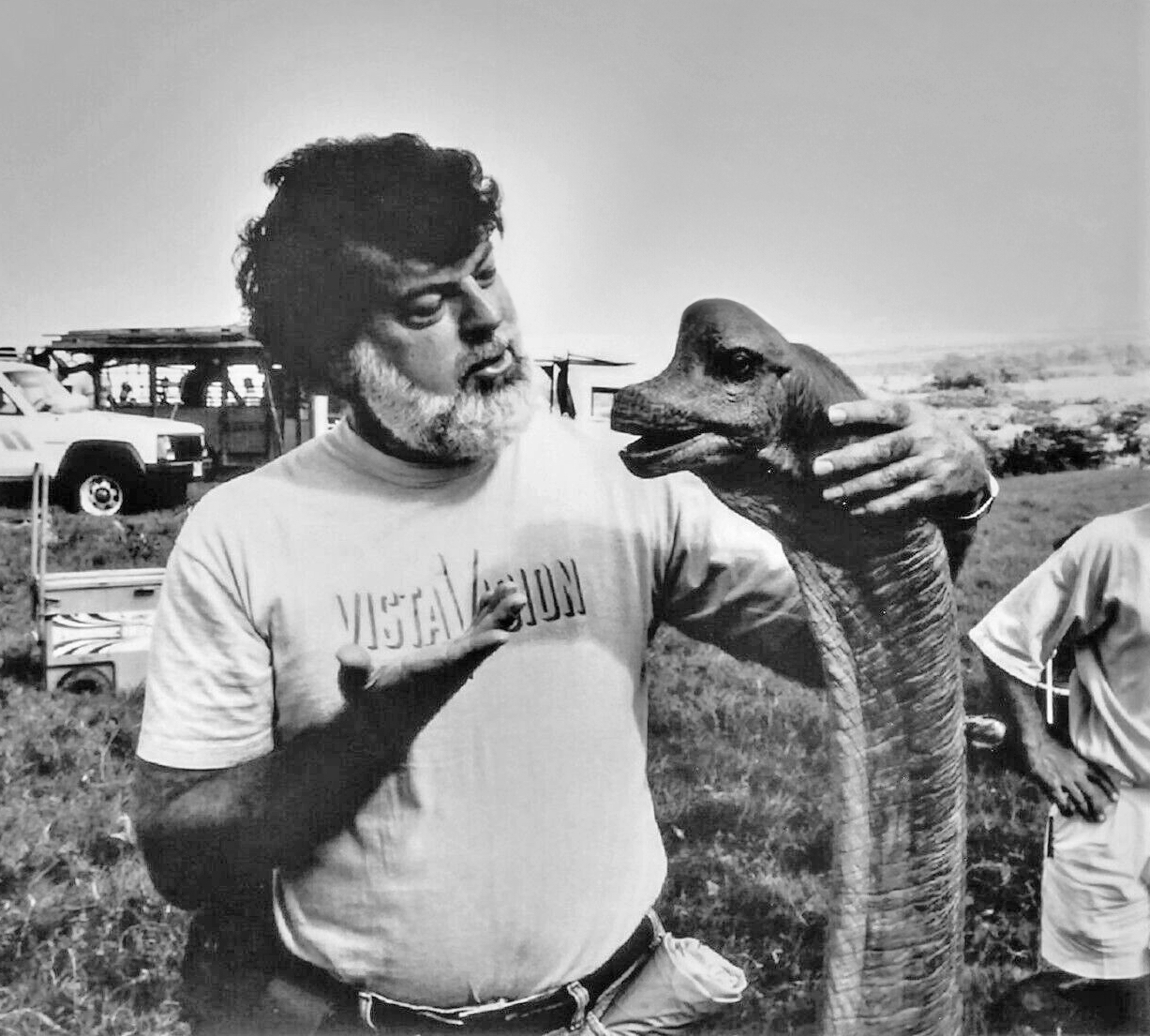

"I don't think you can fool them with people in rubber suits, or conventional stop-motion," Cundey says. "Audiences have become too sophisticated to be fooled by our old tricks. But I think they are going to be startled. It's not just the digital dinosaurs. The mechanical puppets are the best I've seen. The 18-foot tyrannosaurus rex is based on the same flight simulator used for training F-14 pilots. It's all computer-controlled, with very sophisticated hydraulics. Its movements are so realistic that it is easy to start feeling like you are out there with a real dinosaur."

Even with top-notch props, however, the ultimate success of a project boils down to capturing the action on film. Except for some action sequences, where Cundey used a second camera for coverage, Jurassic Park was a one-camera shoot. He used a Panaflex Platinum camera with Primo lenses for interiors, and usually a Primo zoom for variable focus on exteriors. No diffusion or filters were used to alter the quality of the image. The movie has a straightforward, clean look which Cundey describes as "heightened reality.”

"Steven believes in visual storytelling," Cundey says. "He understands the importance of setting the mood with light and creating arresting images for the audience. That made it easy for me to say, 'It would look really interesting if all the light came through that window, and the guy is in silhouette, and then he steps into a pool of light. You can say something like that, and he understands exactly why. Other times, he'll come up to you and describe a look he wants to see."

In one sequence, the characters portrayed by Attenborough, Neill, Dern and Goldblum have retreated to a bunker which had been built in case of a mishap. Spielberg wanted a dramatic look, dark but still in daylight. "We decided that all of the light sources should come from some very small windows," Cundey says. "We looked for angles where we could backlight. We put a little smoke in the room. That allows the audience to see shafts of warm light slicing through the darkness. Once we did that, we were able to block the scene and move the actors around. We framed a window between two people, and used some rim light. It's a very dramatic setting which helps establish the mood. The characters realize that everything has gone wrong, and they have to come to terms with that reality."

Cundey used just about every device there is for holding and moving cameras, including tripods, camera cars, PeeWee and Fisher dollies, a Chapman crane, a Steadicam and a Matthews crane with a CamRemote head. "I used the Cam-Remote a lot to put the camera in places we couldn't get to with a regular dolly," he says.

That same versatility applied to the lighting. Just a few years ago, Musco lights were revolutionary. On Jurassic Park, Cundey used just about all of the mobile lighting tools available, including Night Sun and Night Light, for both daylight and night exteriors on the jungle set and in Hawaii.

"We had a big 20K incandescent light," he says. "It gave us a single source, and a single shadow. It gave us a believable source of sunlight, which meant that we didn't have to open up the camera lens too much. So we were pulling a deeper stop. Those are all of the tilings which tell the audience at some subconscious level whether your are really outside or not.”

Cundey also made occasional use of the new slant-focus Panavision lens, which can be adjusted to move the field of focus from side-to-side to front-to-back. “We used to have to struggle with a split diopter in front of the lens, to hold focus from the foreground to the background," he says. “This lens makes it a lot easier." The slant-focus work can be seen in a brief scene in which one of the film's two youngsters occupies the foreground while a dinosaur looms in the background. Cundey wanted to hold them both in crisp focus to make the threat more immediate and menacing. If one of the figures had gone soft, the feeling of imminent danger would have been weakened.

In another scene, Cundey used the slant-focus lens to show a character working at a computer console. He wanted the actor in sharp focus, with all of the labels on the console readable. “It helps the audience understand a key story point," he explains. These aren't the types of shots that movie critics write about. They tend to be taken with landscapes, sunrises and sunsets. But it is this attention to detail that draws the audience into a film, and keeps them involved in the story.

“One of the things which intrigues me about filmmaking is the ability it gives you to create an illusion by getting the audience to believe something you have invented," says Cundey. “It must be the same for actors, writers and directors. I don't mind being stereotyped, because right now, I'm enjoying the films I'm shooting. But I'll admit, there are times when I dream about shooting a film with two actors in one room.”

You’ll find much more on the groundbreaking digital and practical effects created for the film here.