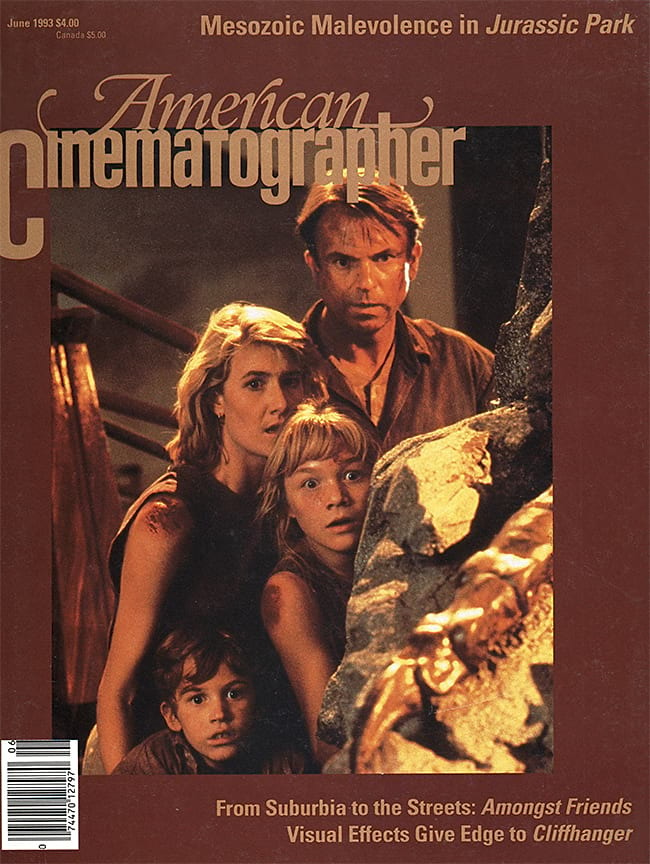

Jurassic Park: Effects Team Brings Dinosaurs Back from Extinction

Stan Winston and Michael Lantieri detail their real-world practical solutions to creating the film’s huge stars.

The jeep heads right for us, the driver so terrified he smashes into a log, shearing the windows and the seat backs clean off as the vehicle skids under, spinning almost out of control. A roar echoes from the dense grove behind the jeep; trees shudder, toppling down, crushed by some monstrous weight. Then it appears, its vast body supported by two powerful legs, its voracious jaws filled with teeth the size of daggers — a living Tyrannosaurus rex. The huge creature gives chase, careening through the mud. The T-rex smashes through the log, reducing it to kindling, then crashes into the jeep, denting its side and upending it into the mud. The driver and his companions stumble from the wreckage as the fearsome beast, more terrifying than any dragon of legend, chases them deep into the dense jungle of Jurassic Park.

This startling sequence, filmed in a single breathless shot, is one of dozens of collaborations between full-scale dinosaur creator Stan Winston and mechanical effects supervisor Michael Lantieri on Steven Spielberg's long-awaited adventure epic. Along with stop-motion animator Phil Tippett and ILM visual-effects supervisor Dennis Muren, ASC [whose contributions are further detailed in AC July, 1993], Lantieri and Winston round out Jurassic Park's revolutionary dinosaur-design team.

Using every known effects technique, and some they created out of necessity specifically for Jurassic Park, they may well have done the impossible: given convincing life to an unholy menagerie of creatures who haven't walked the earth in millions of years. It’s an achievement that may well change forever the way we look at effects films.

Lantieri and Winston's work was used almost exclusively for the live-action dinosaur effects during principal photography. Together, they helped one another solve problems that have plagued effects experts such as Willis O'Brien from the prehistoric era of cinematic illusion — the silent The Lost Continent and the legendary King Kong — to the present day. “We really worked as one crew," Lantieri marvels. “Early on, our four-person design team took this pie, which represented all of the effects in Jurassic Park, and cut it up. We figured who could best do each effect, and then one or the other would say, 'We can go so far with this; can you pick up from here and run with it?'"

In the beginning there was Stan Winston. As the multi-Academy Award-winning makeup effects artist will tell you, every dinosaur created for Jurassic Park began on the drawing boards at his Stan Winston Studio in Van Nuys. The bearded makeup impresario is a cagey fox, dazzling his audience with reams of techno-jargon, but the man has undeniably produced some of the most remarkable creations in screen history: the xenomorph queen of Aliens, the Pumpkinhead demon (from the film he also directed), the robotic cyborg of The Terminator and the shape-shifting T-1000 in Mark 'Crash' McCreary.

What gives Winston's mechanical marvels their edge seems to be a philosophy stemming from his own humble beginnings as a struggling actor who fell into the field he now dominates almost by accident. "I got involved in a makeup apprenticeship program while I was waiting to be a star," he admits. "I was a big Lon Chaney fan and I was inspired by him to create wonderful, bizarre and incredible fantasy and real characters for film. When I realized a prosthetic makeup on an actor's face wouldn't allow me to fully realize the characters I was asked to create, I began using special effects technology to create fantasy characters that were completely animatronic puppets. I haven't gone from makeup to special effects; I have increased my palette with more colors that allow me to create characters using all the technology available, be it a makeup, a prosthetic, or dinosaurs for Jurassic Park." Unlike others in Winston's field, he sees his creations as characters who have to perform, on cue, like any other actor. This makes his task more demanding, and more rewarding.

“I haven’t gone from makeup to special effects; I have increased my

palette with more colors that allow me to create characters using all

the technology available, be it a makeup, a prosthetic, or dinosaurs for

Jurassic Park.”

— Stan Winston

One and a half of Winston's two years on Jurassic Park were spent designing the creatures who populate fictional billionaire John Hammond's bizarre island amusement park. All told, Winston's crew visualized nine different species of dinosaurs, most prominent of which were two-legged predators such as the Tyrannosaurus rex, velociraptors [above], and "spitters," [the dilophosaurus] along with four-footed vegetarians such as triceratops and the mammoth brachiosaurus. "Steven felt that there should be a consistent dinosaur design," Winston explains, "so even dinosaurs that were only realized in the computer at ILM, such as the ostrich-like gallimimus, were designed here. The approach is very simple and it's what we do on every project: artistically, everything starts on the drawing boards. We're certainly not going to throw two tons of clay at an armature and start sculpting a full-sized Tyrannosaurus rex and hope that it looks great! On Jurassic Park, our concept artist was Mark 'Crash' McCreary, who did all the final renderings of the dinosaurs. The creatures' skin coloring was created by Shane Mahan and John Rosengrant, among many others."

Once the designs were finalized on paper, Winston's crew created 1/5th-scale sculptures of each dinosaur, except for the brachiosaurus, which was so huge in life that Winston opted to do him as a 1/19th-scale model. These clay maquettes were molded, cast in fiberglass and painted not only to show Spielberg what the creatures would look like in three dimensions, but also to serve as the models for the computer-generated dinosaur effects created by Phil Tippett in conjunction with ILM and Dennis Muren. Winston's crew also fabricated 1/5th-scale mechanical versions of each character destined to become a full-scale animatronic puppet.

Winston says it was a brainstorm in the middle of the night that led him to devise a system for exactly translating his miniature dinosaurs into their full-scale counterparts: using cross-sections taken at precise intervals from his 1/5th-scale dinosaurs, he had them blown up five times and made into wooden patterns which were then strung along metal spines. "We covered the wooden patterns with fiberglass to create a smooth solid surface, then started putting clay on it to make our finished sculpture," Winston boasts, "and that became our sculpting armature. It ended up looking exactly like a very large version of those wooden dinosaur skeleton toys you can buy! The form of the dinosaur was done virtually by mechanical drawing, so our full-scale creations were identical to our 1/5th-scale maquettes. All we had to do then was to sculpt the skin and the detail. Later I learned this was exactly the way the Statue of Liberty was built!"

Each of the full-scale dinosaurs, which included the Tyrannosaurus rex, the spitters, the velociraptors, a triceratops and an insert brachiosaurus head and neck, took teams of sculptors months to craft to Winston and Spielberg's satisfaction. The sculptures were then molded, and from these molds flexible skins were cast which were then fitted over graphite and metal skeletons laden with all manner of mechanical devices: air bladders to simulate breathing, cable-actuated systems to perform certain body movements, radio-controlled servo motors to control facial motion. The creatures were all designed to operate in real time.

Meanwhile, mechanical effects supervisor Michael Lantieri was hard at work creating what the four man design team laughingly called “dinosaur interfaces,” mechanical systems that would help these full-scale behemoths to stand, walk and perform in scenes. "We always joked that Stan got the glamorous end of it," Lantieri says, "but the behind the-camera work turned out to be really important and Stan was great about including us. We really worked together. If he'd made a creature that was only there from the waist up, we built out of our special 'dinosaur interface' things that could be attached to the creature to move it. Stan and I talked about where we could attach our interfaces, how we would move them and the speed [we would use]. We built a lot of different rigs that would accommodate Stan's puppeteers, underground cranes and dollies, as well as pneumatic cranes that would assist with the broad movements. In addition, my guys would be involved in the shoving and pushing needed to give the full range of motion."

Of all the life-size dinosaurs, the velociraptors embody the most controversial blending of techniques: at the core of several of the various effects models are human beings. Given the dubious legacy of el cheapo productions such as Unknown Island, The Land Unknown, and Japan's legendary contribution to the genre, the Godzilla series, the idea of man-in-a-suit dinosaurs has been reviled by cineastes from time immemorial. Today, the man-in-a-suit approach has become state-of-the-art, and Winston is almost single-handedly responsible for the public's dramatic change in attitude. "If there was a man inside a dinosaur, there was a great deal of technology inside that dinosaur, too," Winston observes.

"For Jurassic Park, we designed and built full-sized, performing, live-action dinosaurs. The methods we used involved whatever technology was required to create the performance needed. We built two man-in-suit raptors and two fully animatronic, no-human-being puppet raptors utilizing a combination of cable and servo control. We also made a set of walking legs and a set of running legs from the waist down. For certain shots, we created insert hands which could, for example, open doors. Then we fabricated our stunt raptors, full-sized floppy puppets and poseable puppets. All told, we built 8 to 10 full-sized raptors that did different things. We also built a baby raptor splitting out of its shell [seen featured image at top of page], which was totally real-time using cable control."

Winston's goal was to create fluid, believable dinosaurs that bore no trace of the mechanics which gave them life. Specifically, he wanted to conquer the phenomenon he refers to as "waga-waga," which he scientifically defines as the jolt that occurs when a large moving mass comes to a stop. Such jolts, which mimes employ to simulate robotic movement, work fine for machines like in The Terminator, but they would have seriously undermined Winston's attempt to bring his dinosaurs to convincing life. Through the careful application of some unusual, though strangely related technologies, the raptors and some of Winston's other dinosaur creations, most dramatically the full-scale Tyrannosaurus rex, employed a breakthrough "anti-waga" system. They were dubbed "Steadi-Dinos" because their movements were based on neutral buoyancy, the same principal which is integral to the Steadicam. This concept was envisioned by Craig Caton, one of Winston's key mechanical designers.

"I saw the relationship between a person having a hard time trying to hold a camera at the end of his arm and the need to hold up a head mechanically on a long neck," Winston beams, "and I realized that the same wonderful system of counterspringing the camera so the weight load becomes neutral could help us mechanically. We realized that this could work very well for us in terms of certain head and neck movements, to make everything fluid. The actual infrastructures of our dinosaurs were countersprung just like a Steadicam, which made our creatures' movements totally fluid and organic. That technology went into the spitters and the velociraptors, two of our most active dinosaurs."

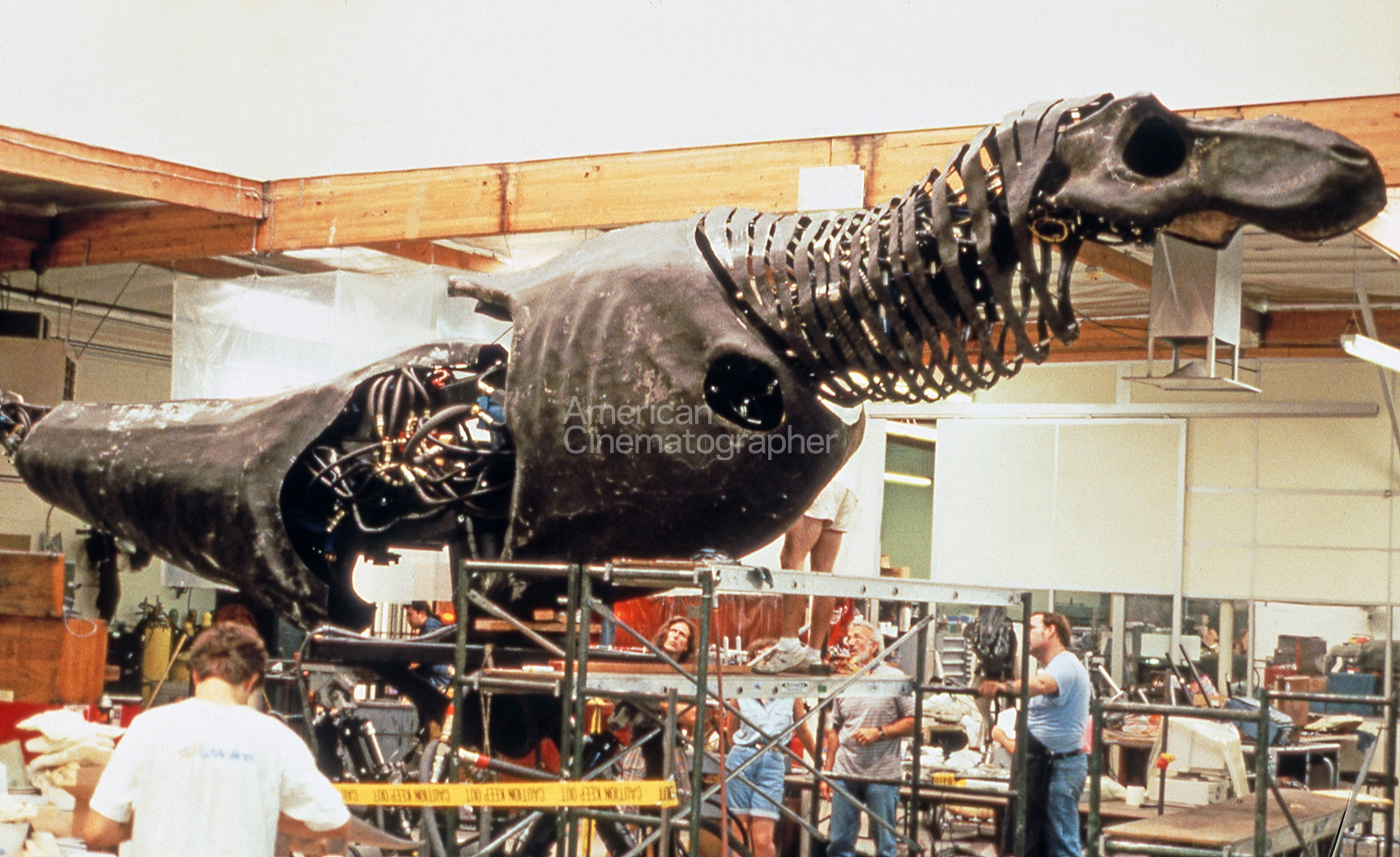

But this system achieved its most remarkable results in Jurassic Park's star attraction, a 40'-long, 9,000-pound animatronic machine that perfectly recreated the appearance and fluid motion of a full-sized Tyrannosaurus rex. "The technology of the T-rex is beyond anything I think anybody has ever seen," Winston says. "One of our big problems was figuring out how to make this 40'-long creature move quickly and violently, perform wonderfully, yet come to a smooth stop on cue without the waga-waga you would expect. We solved the problem through a series of computer-involved aspects of ramping up and ramping down speed, and by building accelerometers into our anti-waga devices. A series of accelerometers enabled us to measure the speed of the hydraulic rams moving within our dinosaur, which allowed us to counter that movement with other rams moving in the opposite direction elsewhere in the body. So our T-rex never completed a particular move and stopped without another aspect of the body compensating immediately. In order to keep this creature moving with speed and dynamics, nothing was allowed to come to a hard stop against its rigid 9,000 pounds without something else counterbalancing that motion. When its head comes to a sudden stop, something moves in the neck to compensate for it at that exact split second, which acts as a shock absorber. It's wonderful how this guy performs — he’s fast and big and dangerous and he's a great actor."

Winston was concerned that the T-rex, weighing in at 9,000 pounds, was potentially as lethal off camera as on, and he began to worry about how to control this gigantic performer so it would interact on cue with its environment and not present a safety hazard. "Unlike any other hydraulic creature you've seen in an amusement park, say King Kong [at Universal Studios], whose specific moves have been programmed in over a long period of time and who repeats those movements over and over, our Tyrannosaurus rex was this big hydraulic machine that had to perform on cue," Winston states. "When you're an actor in a film, you have to be able to take direction immediately, so I was concerned about how to coordinate the computer keyboards with 8 or 10 people on them to make these big moves. The biggest problem we had beyond all this technology was safety. There's a real big danger factor working on a set with a 9,000-pound machine. This dinosaur could've killed someone really easiiy."

As with many of Winston's best ideas, the ideal solution to this hazard presented itself in the middle of the night. Winston had worked with performance Waldos many times before, but these telemetry suits, which translate the motion of the person wearing them into the performance of the mechanical creature itself, were designed for more humanoid characters. No one had ever devised a telemetry system for creatures that didn't mimic human motion. "Thinking back to our 1/5th-scale mechanical T-rex prototype, I had the brainstorm that we could actually use one similar to it as our telemetry puppet!" Winston says. "I realized that we could literally build a performance Waldo for the T-rex that duplicated every motion he made in 1/5th scale, and use that as an interface for us to organically puppet the creature. Instead of having linear potentiometers linked to a control board, each potentiometer would correspond to a cylinder in our puppet version of the T-rex, so we had a 9,000-pound puppet that was literally operated by puppeteers manipulating a small version. That way, Steven could say, 'Let him rear up' and we could pull our 1/5th-scale Waldo back and let him act; our full-scale T-rex performed on the spot. If a situation required a really critical move, we could puppet it on the fly, and then, using the computer system that controlled our T-rex, we could record that move and repeat it over and over again at the push of a button."

The animatronic Tyrannosaurus rex was built in two parts. The upper body from head to tail down to the knee made up one section, while the legs comprised the other. The two sections could appear to be one creature by strategically placing a tree branch across the joint, there was also a set of dummy legs that could be positioned under the mechanical upper body. The effects team also constructed a foresection of the T-rex consisting of the front half of his body, which at 4,000 pounds was easier to move around than the full 9,000-pound version.

The gross movements of the nose to tail T-rex's massive upper body were controlled via a motion platform Winston calls the "Dino-Simulator" because of its similarities to a flight simulator, a hydraulically actuated, computer-operated platform capable of handling all six axes of movement smoothly, even while bearing an enormous weight load. Winston stresses that the full scale T-rex's articulation was tied directly into the flight-simulator concept. "We took that same technology and, like branches on a tree, moved it right out to the tip of its nose," he says. "The basis for the hydraulics and the mechanics and the fluidity of the T-rex's movement was the methodology behind flight simulators. The Dino-Simulator could fluidly move the creature forward, back, from side to side, and up and down. We took that system and continued to work up into the beast with hydraulic cylinders, transducers, and the addition of accelerometers, so what worked the Dino-Simulator also moved the entire dinosaur. Our problem was that it wasn't enough for the T-rex to move fluidly; it had to perform, so we had to take another step because now we had a long load-bearing situation that was setting itself up for an amazing waga! The solution involved computer cards to rapidly ramp-up and ramp-down speed, combined with counter-moves to stop the waga."

Assisting with the construction of the Dino-Simulator was only the tip of the T-rex for veteran floor effects specialist Lantieri, who gives off the impression of a youthful elf with enormous enthusiasm for the problem-solving that comprises most of his work. It's hard to believe he got his start some 20 years ago handling effects for The Six-Million Dollar Man series at Universal Studios, where he now works his magic from his permanent, Spielberg-funded workspace on the lot. Along the way, Lantieri has won two Academy Award nominations and three British Academy Awards for his ability to contribute invisible expertise to such landmark productions as Who Framed Roger Rabbit and the Back To The Future films.

Even with all of this experience, however, Lantieri had never faced problems like those confronting him on Jurassic Park: "Once you bring a dinosaur in for a shot, then what do you do with it? Not only did we have to move our creatures within the shot, we had to move them into position for the next setup. We had to be able to turn them around and move them out of the way. This meant we had to build very dinosaur-friendly sets to accommodate our winches and cranes and air bearings, most of which helped move the creatures into position and also, for certain shots, handled some of their broad movements in conjunction with Stan's puppeteers.

"We literally built a walker with training wheels to move the full set of T-rex legs. We also mounted the Dino-Simulator onto a tower that I built which was on air bearings, so we could use high-pressure air to glide a great deal of weight. Air bearings are used for moving heavy equipment out in the real world, but we use it for simulating earthquakes and other effects where we move big, heavy objects."

Such as 9,000-pound dinosaurs. This concept brings us back to the aforementioned shot in which the tyrannosaurus rex wreaks havoc on a jeep. "The T-rex was supposed to give chase, run through a grove of trees, break through a gigantic log that's fallen across the road, then slam into the jeep," Lantieri smiles, pausing to catching his breath. "Naturally, Steven wanted it in one shot. Upon the action cue, we were controlling half a dozen large real trees that had to be mowed down in sequence before we even see the T-rex. Each tree had to be scored, precut and hinged using internal cables, as well as cables on a pulley at a 45-degree angle. We set off sequential charges in the trees and had them spring loaded so they'd seem to plow from the back forward.

"Then we had this tree that had fallen across the road, which had to rip the windshield and shear the seat backs off our jeep as it crashes under it, but then break as our T-rex plows through it!" Lantieri says, shaking his head. "The fallen tree was built as a hollow log. It was made out of steel, then skinned with fiberglass and real bark and real limbs and real leaves. We then put a big air-driven piston through the center of it, so that when it was closed, just like a big barrel bolt, the log was sturdy and sound. The jeep actually drove into it at 30 m.p.h. and sheared the windshield off as everyone ducked at the last second, which was a real stunt that Gary Hymes supervised.

"A beat behind that, in the same shot, the T-Rex plunges through this log chest-first, which meant that we had to weaken the log and cause it to break itself open so we didn't hurt our creature! The second the jeep went through, I used high-pressure air to pull the piston and create a weak joint in the middle of the tree. The tree was then pulled back from the outside edges using hydraulics, like a swinging barn door, so that at the moment of impact with the T-rex we didn't hurt our star dinosaur.

"Lastly," Lantieri says with visible relief, "we kept the shot going as the T-rex hits the side of the jeep, denting it and causing it to raise off the ground. Since our 9,000-pound animatronic puppet didn't have the strength to do what a real T-rex weighing 20 tons might do, we had to build a jeep that would dent itself on cue and appear to raise off the ground from the impact! We had the entire side of the jeep rigged with pneumatic rams and covered with lead sheets painted to look like the genuine steel skin. The ram, which was extended and welded to the lead skin, was then closed at high pressure at the moment of impact with the T-rex, and it sucked a great big dent in on the side of the jeep. We also had a pneumatic foot hidden behind the rear tire that slammed down into the ground and lifted the jeep off the ground, all of which had to be timed to the movement of the creature. This whole sequence was done in one shot, so you can imagine the amount of timing and cueing required in order for my crew and the stunt people to all hit their marks at the right moment. That was a huge mechanical effect." For added protection, the shot was also done as a motion-control move minus the T-rex, which could then be added later by ILM.

The film's most elaborate mechanical effects set piece again involved the Tyrannosaurus rex, who ravages a two-car caravan on a tour of Jurassic Park. The tour vehicles were supposed to be driverless Ford Explorers on a magnetic track. In reality, they were either radio-controlled or blind-driven vehicles which a driver controlled from underneath the hood. Lantieri had gained a lot of experience with these systems on Roger Rabbit, but he had never created a car that would literally crush itself. "The crushable car was a real Ford Explorer," Lantieri explains. "We replaced the door panels we wanted to crush with lightweight aluminum and lead, and we created replaceable, crushable roofs as well. We built a telescoping roll cage inside the headliners of the car, which was what actually pulled the roof down. We also had metal buckling on the side and glass breaking. It was all hydraulically driven, like a big crush press that we could control with joysticks. We stood right by the camera and Steven would say, 'Crush it a little more... a little more.' We were trying to give the feeling that this creature's foot was actually on top of the car, crushing it, which meant it couldn't seem like a mechanically clean crush. The car had to rock and crush at the same time, which required some puppeteering. When we shot our pickup scene inside the car with the two kids, we had to be sure that the roll cage was engineered to come to a stop at the right height so it wouldn't harm them, because Steven wanted it to look as if they were almost crushed."

Once the T-rex finishes demolishing the Ford Explorer, he bulldozes it over a cliff, where it lands in the branches of a huge tree. The kids then clamber out of the crushed vehicle as the branches give way, and the car chases them down the tree. The mix of kids and a 3,000-pound falling Ford had all the elements of a full-scale real-life disaster, but both Lantieri and Spielberg were fanatical about safety precautions. "The tree was built on Stage 27, which is a pit," Lantieri recalls. "Our tree was 60' high, and so detailed that its trunk was even covered with rolled bark that would scrape off as the car slid down it. The tree had to hold the weight of the real Explorer we were going to fly down after it got shoved over a cliff, so you can imagine all the safety precautions we had to go through. We used one of our regular cars with the motor removed, so it was just the frame and body, and we removed or replaced every piece that could break off. The only pieces that broke were ones that we controlled so we knew where they were going to fall. The car was always on a cable, but it still had to fall like it wasn't. It couldn't jerk when it fell. We actually put it into freefall using custom-built hydraulic wedges with electronic braking. That way, we could bring the car from a freefall to a controlled stop in one foot and it wouldn't snap on the cables because of the braking. It was all controlled digitally using a system we built combined with a descender rig that was capable of holding three or four tons. That way, we were able to drop a full-sized car on a limb above people's heads and do close calls. It was a tremendous responsibility, as well as a challenge, to make this look real."

To complicate matters further, the entire effect had to be completely timed out to Spielberg's nod. "We had hydraulically controlled branches that would break on cue," Lantieri reveals, "so I could build that cinematic tension that Steven loves to create — he's famous for it. After the car hit, the branch slowly started creaking and bent until he nodded, and then we let the branch break and the car fall. Steven knew exactly the length of suspense that he wanted to build. He'd say, 'Let it slip a little... let it slip... now!' and the car had to go right on the money. And it had to be repeatable. After the tree branch broke, we reset and reskinned it. We were all set to go while he waited, or we wouldn't be there the next day. That's part of the joy and challenge of working with someone like Steven."

Lantieri and company also created the usual atmospheric effects — rain, mist and fog — on set and on location, and also took care of details such as dinosaur tracks and park fences. "Fencing!" Lantieri shrieks. "Let me tell you about a simple job, the kind of thing that would just slide by on this movie. When I read the script, the last thing on my mind was fencing! I was thinking, 'My God, the special effects on this movie! Do I really want this job?' But once we got the drawings and they said, 'Okay, just go put some fence up for us,' well, that took months."

And yet, Lantieri concludes, "I'm wondering where I go from here. I hope that having the opportunity to work on this film, with Steven as our fearless leader, wasn't a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity."

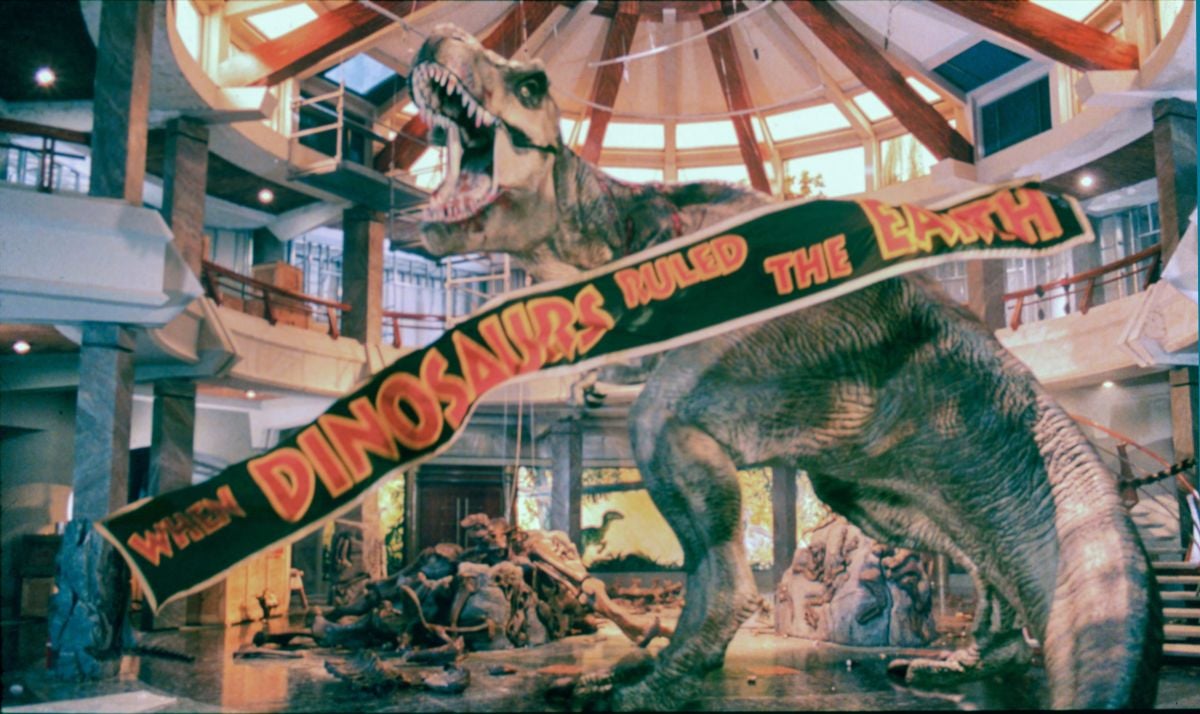

Winston concurs, adding: "To me, the most exciting thing about Jurassic Park is that these dinosaurs are beautiful, they're real, and everything about their movements and their looks is organic. Some of the finest artists in the world worked for the longest time designing them, creating their look, their texture, and their movement, and the piece de resistance is the fact that they do perform and that they can act. And when they can't do something, that's where ILM and Dennis Muren come in. It'll be a beautiful, seamless mix of technologies so that what you see are living dinosaurs that are almost too real to be real."

Also from the June 1993 issue of AC is Jurassic Park: When Dinosaurs Rule the Box Office, in which cinematographer Dean Cundey, ASC details his approach to the project.