Key Light vs. Background Illumination

In this entry in our “Classic Lighting” article series, Karl Freund, ASC details the relationship between lighting, exposure and printing to maintain consistent facial tones.

In this entry in our “Classic Lighting” article series, the author details the relationship between lighting, exposure and printing to maintain consistent facial tones.

By Karl Freund, ASC

One of the most frequently misunderstood aspects of lighting is the relationship between keylighting and background illumination. In professional cinematography, we normally light, expose and print to obtain a normal tonal and textural value of the face of the principal player or players. Yet the background may be of high or low reflective value — that is, anything from pure white to jet black, including, of course, any conceivable light or dark coloring.

We can and do further complicate this by increasing or decreasing the amount of illumination falling on the background. As is well known, one can control the tonal rendition of any surface, almost regardless of its inherent coloring or reflective value, by giving it more or less illumination. It is quite possible to make an actually black surface photograph almost white by sufficient overlighting, and to make a white surface appear black by simply keeping the light away from it.

Yet all too often in both technical discussions and actual practice; we find even experienced cinematographers giving evidence that they do not clearly understand the relationship between keylighting, which governs facial rendition of the players, and the reflective value and illumination of the background. Sometimes we find them advocating changing the key-light level in order to obtain normal rendition and compensate for differing reflective or illumination values in the background. Sometimes we find them urging that even though the key-lighting remain constant between two scenes with photographically light and dark backgrounds, the timing of the final print must be altered to assure that in both takes the face tones will remain normal.

From my own experience, both of these viewpoints are fallacies. In every instance, we have one key factor for which we are shooting — a normal rendition of the tone and texture of the faces we are photographing. Assuming, of course, that the player’s complexion and make-up are such as will give us a normal face to photograph, it is clear that to obtain a normal photographic rendition with a given emulsion and a given normal negative development, there can be but one correct exposure value for that face, and but one correct printer-light setting, regardless of whether the background is photographically black or photographically white, and regardless of whether these background tones are secured by inherent coloring or by under- or over-illumination.

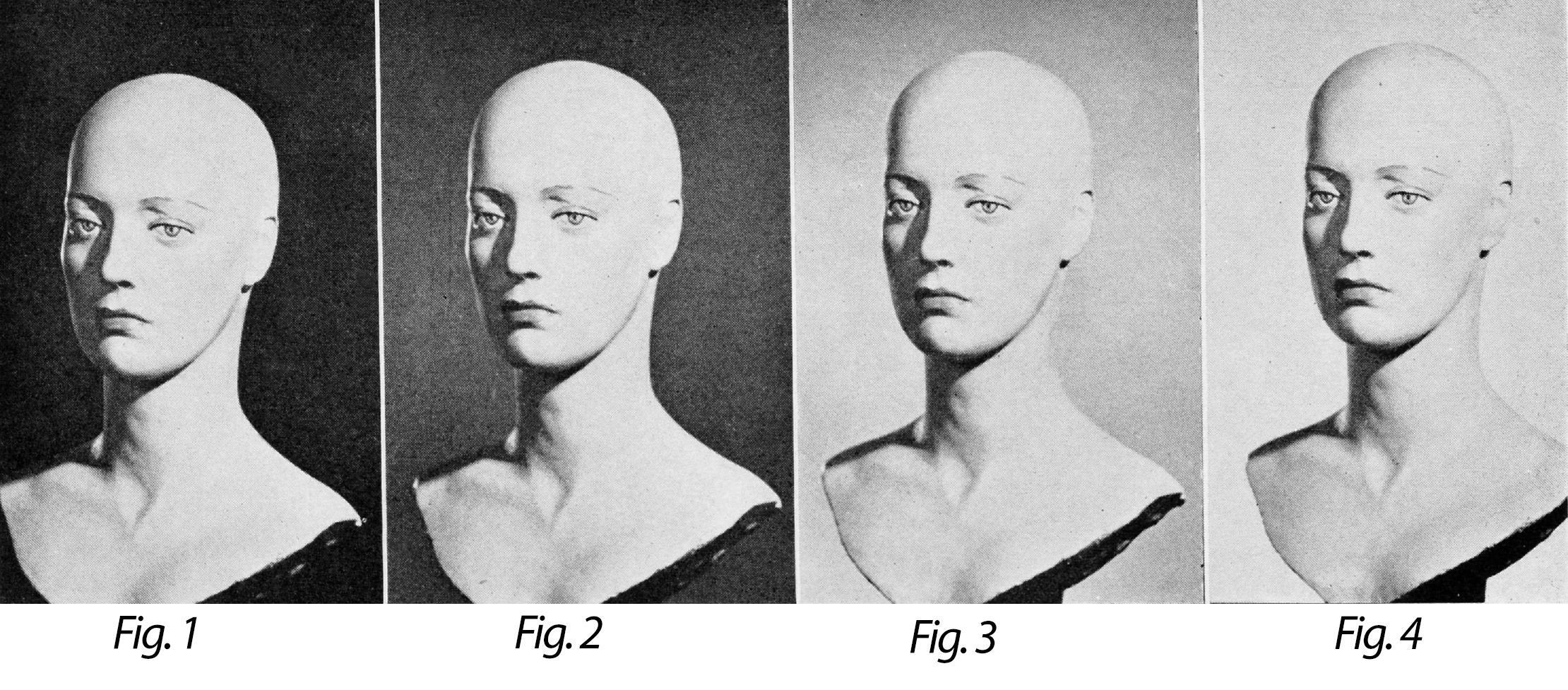

As a means of verifying this conclusion, the Editor of this magazine and the writer recently made a series of simple, photographic tests, some of which are reproduced in the accompanying illustrations. Throughout a series of 30 exposures, the lighting on the subject (a wax figure) remained constant, while the coloring of the background was successively changed from black to gray to white, and the illumination thereon was also varied. Different overall exposures were given for each change of background or background-lighting, and the negative was printed with three different printer settings. The results of this test, which may easily be duplicated by any cinematographer, conclusively proved the above contention.

The tests were made on a single roll of ordinary Eastman Plus-X negative film, exposed in an Eastman “Ektra” miniature camera. The negative was developed by the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studio Laboratory, receiving strictly normal development. Three prints were made, using respectively printer lights 23, 24 (the preferred “normal” for that laboratory) and 25.

The wax head which served as a subject was given a strictly normal lighting, with the key-light, as will be observed from the illustrations, coming from a Baby Junior Solarspot at the right, “filler-light” from a single broad at the left, and suitable top and rim lighting from 500-Watt baby spotlights to the rear and above.

This lighting was balanced to give an f:2.8 reading on a Norwood "Director" exposure-meter calibrated for the MGM Laboratory’s processing. Throughout the entire series of tests, this lighting remained unchanged.

All exposures were made at 1/50th second, corresponding to the usual exposure given by studio cine-cameras at the standard 24-frame sound-speed.

In each test, three exposures were given, respectively normal and one-half stop and one stop above normal; that is, f:2.8, f:2.3 and f:2.

In the first exposure-sequence, a completely black background was used, with no illumination falling upon it. This is shown in Figure 1.

In the second exposure-sequence, the black background was replaced by a dark gray one. The illumination was the same : measured by a standard reflected-light exposure meter (a Weston “Master”), the background gave a reading of 0.8 foot-candles. The results, as might be expected, were virtually identical to those obtained in the first sequence.

The third test used this same gray background, but the illumination on it was increased to give a reflected-light reading (background only) of 3.5 foot-candles.

In the fourth test, the illumination on this gray backing was increased to a measured level of 6.5 foot-candles, as shown in Figure 2.

For the fifth test, the gray backing was replaced with a white one, and the background-illumination reduced to a level of 1.2 foot-candles — the lowest conveniently possible with this considerably more reflective surface. This again gave a background which was very nearly black.

In the sixth test, the illumination on the white background was increased to give the same reflected-light reading was that obtained on the gray background in Test 4, that is, 6.5 foot-candles. As might be expected, the result proved virtually identical with that shown in Figure 2.

In the seventh test, the background illumination was virtually doubled, to a reflected-light reading of 12 foot-candles.

The eighth test is shown in Figure 3. In this, the background illumination was increased to give a reflected-light reading of 25 foot-candles, which, it may be mentioned, corresponded to an incident-light reading of f:1 on the Norwood meter. In this, the white background was rendered as a pleasing light gray.

The ninth test increased the background illumination to a reflected-light value of 35 foot-candles, giving an extremely light-gray rendition.

The tenth test, shown in Figure 4, increased the background-illumination to the maximum possible with the equipment at hand, giving a reflected-light reading of more than 50 foot-candles, corresponding to a Norwood incidentlight reading of f:2.5. In this, as will be seen, the background is rendered as pure white, slightly lighter in tone than the rendition of the normally flesh-colored tones of the face.

In all of these tests a fact was observed which it is hoped will also be evident from the illustrations, despite the inaccuracies inevitable with the added variables inherent to magazine reproduction, namely, that regardless of the color or illumination of the background, the face tones, given a single normal lighting, exposure and printing, remained identical – and satisfactory.

A difference in overall exposure of even so comparatively little as ½-stop from the correct value as given by the Norwood meter’s incident-light reading was sufficient to distort the desired tonal relationship between face values and background and — more significantly — to distort the tonal and textural values of the face itself from the desired normal rendition.

ln the same way, printing the scene up or down even a single printer-light setting to correct for differences in exposure balance proved sufficient to distort the facial renditions in the normally exposed shots and failed to restore the desired balance between facial tones and background-rendition in the incorrectly exposed tests.

In other words, it may be concluded that regardless of the color or lighting of the background, there can be but one correct lighting and exposure level to secure normal rendition of facial tones.If this is held correctly constant by mean of incident-light readings by a suitable meter, such as the Norwood, the background and its lighting may be balanced visually, the negative given strictly normal development and printing, with complete assurance that the vital area of the scene — the players’ faces – will always remain correct and content.

Freund’s extensive credits include Metropolis (1927), Dracula (1931), Key Largo (1948) and the seminal 1950s TV comedy series I Love Lucy, for which he created the system of three-camera shooting before a live studio audience that is still used today.