Kill Bill Vol. I : A Bride Vows Revenge

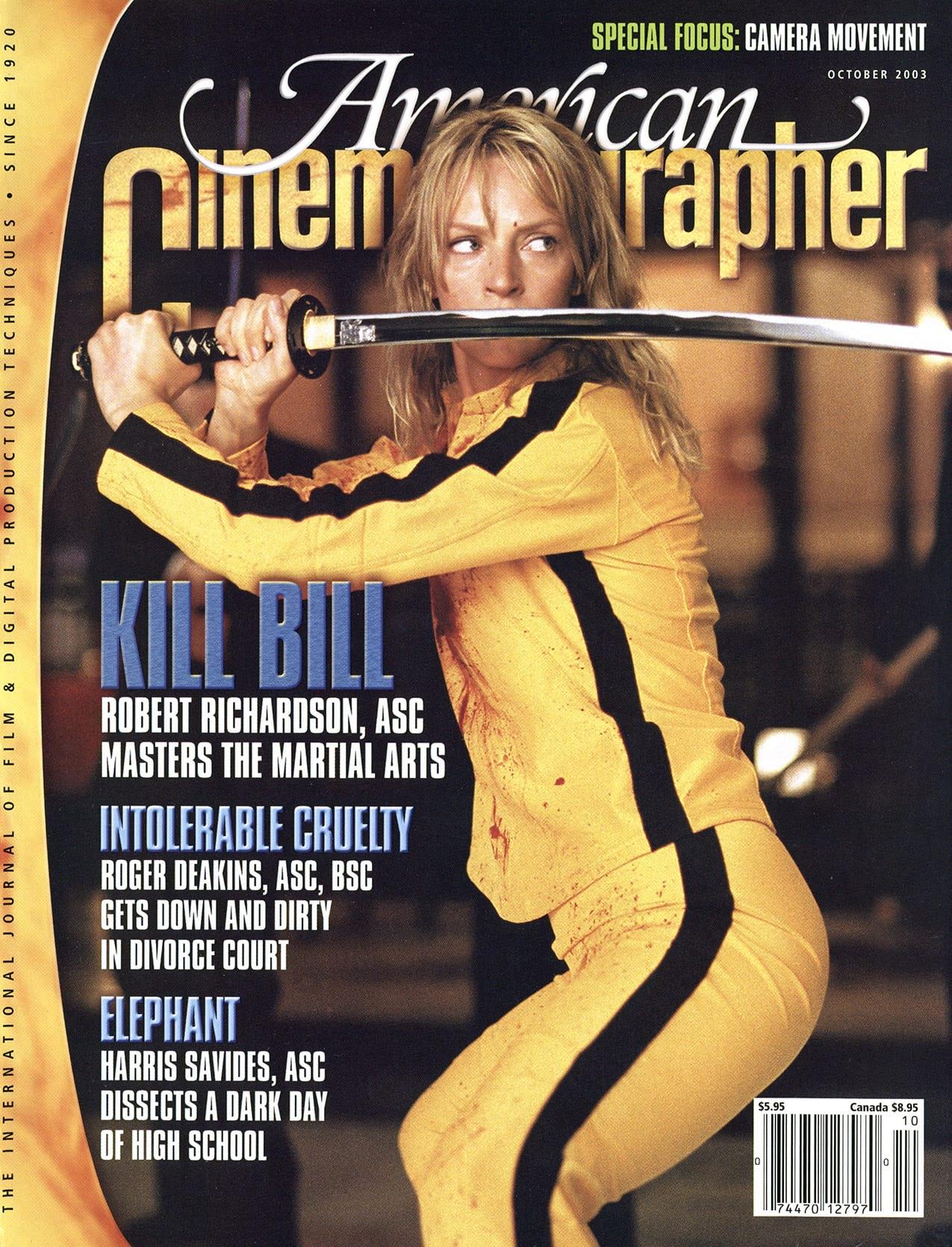

Robert Richardson, ASC lends his keen grasp of aesthetics to this genre-blending martial-arts extravaganza.

Unit photography by Andrew Cooper, SMPSP

“I am first and foremost drawn to the director of a project. The dynamic of this relationship is central.”

— Robert Richardson, ASC

“... even as worn-out clothes are cast off and others put on that are new, so worn-out bodies are cast off by the dweller in the body and others put on that are new.”

— The Bhagavad-Gita, from Richardson’s Kill Bill journal

If Robert Richardson tends to describe his filmmaking loyalties in spiritual terms, he has ample reason. His 11-film partnership with Oliver Stone bears mention alongside such other moviemaking “marriages” as Bernardo Bertolucci and Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC, or David Lean and Freddie Young, BSC. Though Richardson took occasional sojourns with other filmmakers throughout the 1990s, his compass always spun back to Stone. But that changed in 1997, when a disagreement over the schedule for Any Given Sunday forced the partners apart.

Subsequent projects such as The Horse Whisperer, Snow Falling on Cedars and The Four Feathers earned Richardson praise from peers and critics, but have so far failed to yield sustaining relationships. His collaborations with Martin Scorsese (Casino, Bringing Out the Dead and The Aviator, the last of which is currently shooting in Montreal) would seem to indicate a budding partnership, but Richardson says he considers himself a substitute for the director’s more frequent cohort, Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK. As for Stone, Richardson says they have reconciled, but admits that “Oliver has gone on to establish new relationships in other capacities.”

They say you can’t expect to catch lightning in a bottle, but this is Hollywood, and bottles have nothing on modern courier service. On Valentine’s Day 2002, Richardson opened his front door to a bouquet of roses and a parcel. Inside was the screenplay for Kill Bill, Quentin Tarantino’s “chopsocky” opus. Richardson’s reaction was swift. “I’ve never heard Bob more excited than when he started talking to me about Kill Bill,” recalls Ian Kincaid, Richardson’s gaffer on the show. “You read the script and you immediately think, ‘Robert Richardson should shoot this.’ You just know that he and Quentin were meant to do this movie together.”

Indeed they did, and in the months following Kill Bill's completion, the silver-maned cinematographer would categorically describe the experience as “the purest rhythm I have had with a director — ever.”

Feb. 16 [first meeting]: On the edge. Nervous. Unusual. Perhaps not so unusual... Quentin arrives. At once — ease. A warm spell cast over the table. I am weary from three nights of commercial shooting, but regardless of how low the eyelids hang, there is the dimension of a dream taking place. Quentin tells me that my letter took him by surprise and “oddly moved” him. A handshake thrusts me into the future.

March 11: Bracelet fell off today — second time. A lost bracelet brings bad luck. Must remedy the problem, otherwise my superstitious mind will take control.

March 12: Repaired bracelet myself— bonded to wrist — will not let Kill Bill go.

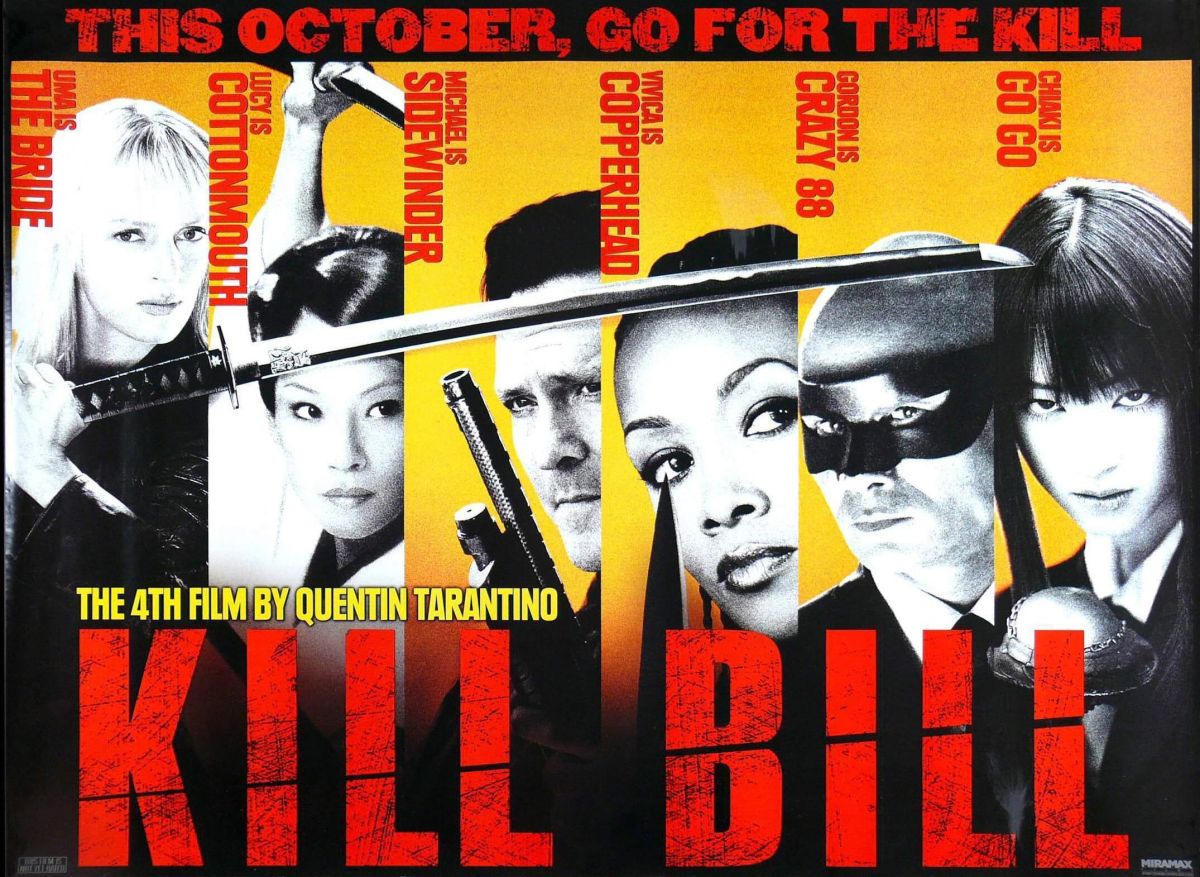

Kill Bill's script is an unabashed kung-fu blowout, and Richardson was enthusiastic about its visual potential. Dubbed half-seriously by its author as “the biggest B movie ever made,” Kill Bill pays tribute to all things “exploitation”: samurai swordsmanship, Hong Kong “wire-fu,” blaxploitation funk, Spaghetti Western standoffs, gangland vendettas, sexy assassins and lots and lots of raspberry-red blood. (In true B-movie spirit, the plot is as cheekily monosyllabic as the title: an underworld boss named Bill double-crosses a hitwoman known as The Bride, who then embarks on a mission to — well, you guessed it.)

“One of the first statements Quentin made was that he wanted each chapter of the script to feel like a reel from a different film,” Richardson recalls. “He wanted to move in and out of the various signature styles of all these genres — Western, melodrama, thriller, horror. He had an absolute knowledge of what he wanted each sequence to look like.”

Richardson adds that Tarantino’s chapter concepts were so specific and varied that the director initially considered hiring three cinematographers for the project, “but in the end, Quentin decided to hire just one person, probably to help keep things consistent over such a huge production. I had sent him a letter expressing my enthusiasm for the script, and eventually I was chosen.”

Richardson closed his deal and sidled into a 10-week-long tango with his new collaborator as they prepped the project. “I was patient not to rush for answers,” he recalls. “That’s a lesson that anyone who wishes to be a cinematographer should take note of.”

March 5/6, 7-11: Films arrive. Designing the days to allow complete immersion. Schedule: wake at 6 a.m. — finish [watching] film from previous night — make breakfast — pack lunches and take the girls to school. Begin films at 8:30; 2:30 — pick up girls. Watch films during dinner with girls — until their bedtime — then continue until fatigued.

Richardson’s legendary zeal for visual research continued on Kill Bill. Between the daily shipments from Tarantino’s assistants and his own purchases, the cinematographer claims he consumed more than 200 films. These included such genre classics as Once Upon a Time in China, Shaolin Master Killer, Lady Snowblood, 18 Fatal Strikes, Carrie and Coffey, as well as obscurities like Reborn From Hell, Texas Adios, Black Mama White Mama and Deaf-Mute Heroine (one of Richardson’s favorites from the bunch).

With a bevy of genres to juggle and a globetrotting production to manage — the film was shot primarily in China, but also included locations in Japan, Mexico and California — Richardson admits that maintaining visual consistency over “the sheer scale of the picture” was his greatest concern. He modestly credits Tarantino’s elaborate mise-en-scène (developed in collaboration with production designers Yohei Taneda and David Wasco) with shouldering most of this burden. “The look of this film was primarily decided well prior to my involvement,” he remarks.

Kincaid, Richardson’s gaffer since The Doors, observes, “Bob will give Quentin credit for having lots to say about the film’s look, but it’s more accurate to say that Quentin really inspired Bob to get the look of this picture going. For instance, when you see a blaxploitation movie, you don’t necessarily want to make [your film] look like that, because a lot of them were made at a time when pictures weren’t so attractive! Bob’s got the ability to look into those films and say, ‘This is the essence we have to pull out and use.’”

“When he wanted that particular kind of close-up, with a very specific angle and a very specific size, he’d say, ‘Give me a Leone,’ and I knew exactly what he meant.”

Richardson’s own explanation bears this opinion out: “What I’m going after in [any genre] is what that genre represents: the attitude toward the filmmaking, rather than the filmmaking itself. Take Spaghetti Westerns, for example. How would you describe the fundamental differences between a John Ford film like Stagecoach and a Sergio Leone film like Once Upon a Time in the West? It’s in the angles, the characters, the sensibility that the filmmaker has toward his subject. I consider Leone a master, and his attitude is part of the Spaghetti Western essence that Quentin was after for certain parts of Kill Bill. When he wanted that particular kind of close-up, with a very specific angle and a very specific size, he’d say, ‘Give me a Leone,’ and I knew exactly what he meant.”

Richardson did design a specifically “textural” look for a sequence in which a wizened monk (Gordon Liu) helps The Bride (Uma Thurman) sharpen her fighting skills. “Quentin wanted to replicate the visual generation loss in these old kung-fu films — the scratches, the higher-than-normal contrast,” he explains. Instead of attempting to create the effect digitally, Richardson employed a photochemical process. He began by capturing the action on contrasty Kodachrome color-reversal stock. He processed that normally, struck an internegative from the print and then struck an interpositive from that, and so on. “We just kept making dupes and prints back and forth until Quentin was happy with the look,” he says.

He used six other Kodak stocks for the rest of the film: EXR 5248 and 5293; Vision 320T 5277, 500T 5279 and 800T 5289; and 5222 for black-and-white sequences.

March 27: Quentin's birthday. We are still circling each other as we learn how to communicate. Patience.

April 1: At Technique to discuss digital intermediate — very promising. No extraction issues from Super 35. What are the benefits? What are the risks?

May 10: First test (only test) completed. Spent the evening at Complete Post — pushed quickly and precisely through visual tests but slammed to a halt on Uma’s makeup. I have much to learn about her face. Confidence shattered... I need time.

Richardson says there was never any debate about how to obtain Kill Bill's widescreen aspect ratio. The production filmed in the Super 35mm format using Richardson’s preferred Panavision Platinum cameras, fitted with Primo lenses and configured for 3-perf shooting. Nevertheless, both Richardson and Tarantino had lingering reservations about maintaining visual fidelity in the oft-maligned format, citing traumatic experiences on Casino and Reservoir Dogs, respectively.

Unable to screen first-generation prints, Richardson considered the next best thing: a digital intermediate (DI), executed at Technique. “This is the best approach available right now, and it’ll only get better,” he observes. “There’s no reason it shouldn’t become the mainstream way of doing things.”

But convincing Tarantino wasn’t so simple. As leery as the director was about Super 35, he was even more wary of anything labeled “digital.”

“Quentin doesn’t like that word,” Richardson says. “I’m still intimidated by [digital timing] in some ways myself. It’s like putting me in the cockpit of a 747: what the hell am I going to do besides put it on autopilot? But as you learn, you do become less intimidated, and you can do things that are simply not possible photochemically. In this particular case, I saw the DI as the best way of maintaining control over the imagery, which is why Quentin finally decided to go with it.”

However, shooting with a DI in mind was another story, and Richardson soon encountered the limits of his director’s magnanimity. Simply put: Tarantino doesn’t test. “Actually, his words were ‘Testing is for pussies,”’ the cinematographer reports. “He believes you should be willing to make errors and enter into those errors on the day. And I believe there’s a good deal of truth to that. If you’re willing to take a risk, there’s more to come from it.

“On the other hand,” he continues, “we were doing a lot of things none of us had ever done. I’d never rendered something back out to film before, so I wanted to know how far the texture of this world should go: the details, the subtlety of color, what the quality level would be compared to something [printed] straight onto film. But mostly, my great fear is faces. For any actor I’m going to work with, I really want to know his or her face before I put it on film.”

After “begging, basically,” Richardson was granted two-thirds of a day for tests. “Even though I had a wide array of images over the five-minute test I did, I still don’t know exactly what I can do when I get to the final [output],” he says. “I essentially went off of the level of knowledge I’d gained from shooting commercials, hoping that the majority of it will apply. Where it doesn’t, I know that my knowledge of film craft will back me up.”

May 28: Notice found on the floor to my apartment: “All departments please note: as a brand-new department to the Chinese production crew, grip dept, is involved in the work of camera, lighting, set-production and set construction. All departments are supposed to cooperate and help so as to become accustomed to each other as soon as possible and do better in this new work.”

June 18: The difficulty of filming the martial-arts sequences is beyond what most of us imagined. Quentin wants to shoot shot by shot (editorial order), regardless of the number of lighting shifts necessary. Difficult, needless to say, but if the procedure leaves Quentin more comfortable, we should do it. Critics surround. Let them psychoanalyze themselves.

Kincaid has worked everywhere from Thai swamplands to Vegas casinos, but he admits he had no idea what to expect from the Mao-built Beijing Film Studio. “We sort of thought that it would all be put together with bamboo and who knows what,” he jokes. Though that was hardly the case, the filmmakers still had to do plenty of what Richardson calls “assimilating” during their three-month stay in China. “The idea is to accept another’s way of approach,” he says. “All of [the Chinese] attitudes are distinctly different from yours and mine, from what’s important in their lives to how they make their own films. You have to become accustomed to how they move their gear, how they set up a stage, what they believe functions and doesn’t function, who’s responsible for what job. Shooting there brought [the film] a textural sensibility that would have been extremely difficult to attain in Los Angeles.”

The production’s budget had a longer reach there as well, especially in terms of manpower. “I’ve never been on such a crowded set in my life,” says key grip Herb Ault. “I had at least twice as many grips in my crew than usual. Everybody’s supposed to be equal in a communist society, so they all kind of swarm and get stuff done by sheer number. It got to the point where I just couldn’t get in the way. I would have to tell my translator what I wanted done, and step back.”

Cinematographers, however, take direct communication with their crew for granted, and Richardson found the process especially cumbersome. “I come with a high passion to make something, and I expect everybody else to have that same passion. But you have to enjoy a certain level of communication to get that across, and because few spoke English and I didn’t speak Mandarin, there was a constant level of frustration.”

Eventually, though, the crew found its groove. Dolly grip David Merrill made sets of bilingual flash cards (“If we couldn’t pronounce it, we could always point to it,” says Ault); meanwhile, Kincaid says he and the Chinese gaffer, nicknamed G-San, “taught each other different versions of lighting — and Ping Pong.”

The shoot’s first sequence — known as “Crazy 88,” for the number of Yakuza thugs The Bride kills — turned out to be one of the crew’s most challenging. Four years after surviving Bill’s wedding-day whack attempt, The Bride tracks one of her old teammates (played by Lucy Liu) to a Japanese nightclub called The House of Blue Leaves. Co-production designer Yohei Taneda recreated the Tokyo hotspot plank for plank so that any element — tables, ramps, silkscreen walls and even a bandstand — could be “Hollywooded” in or out depending upon the filmmakers’ needs.

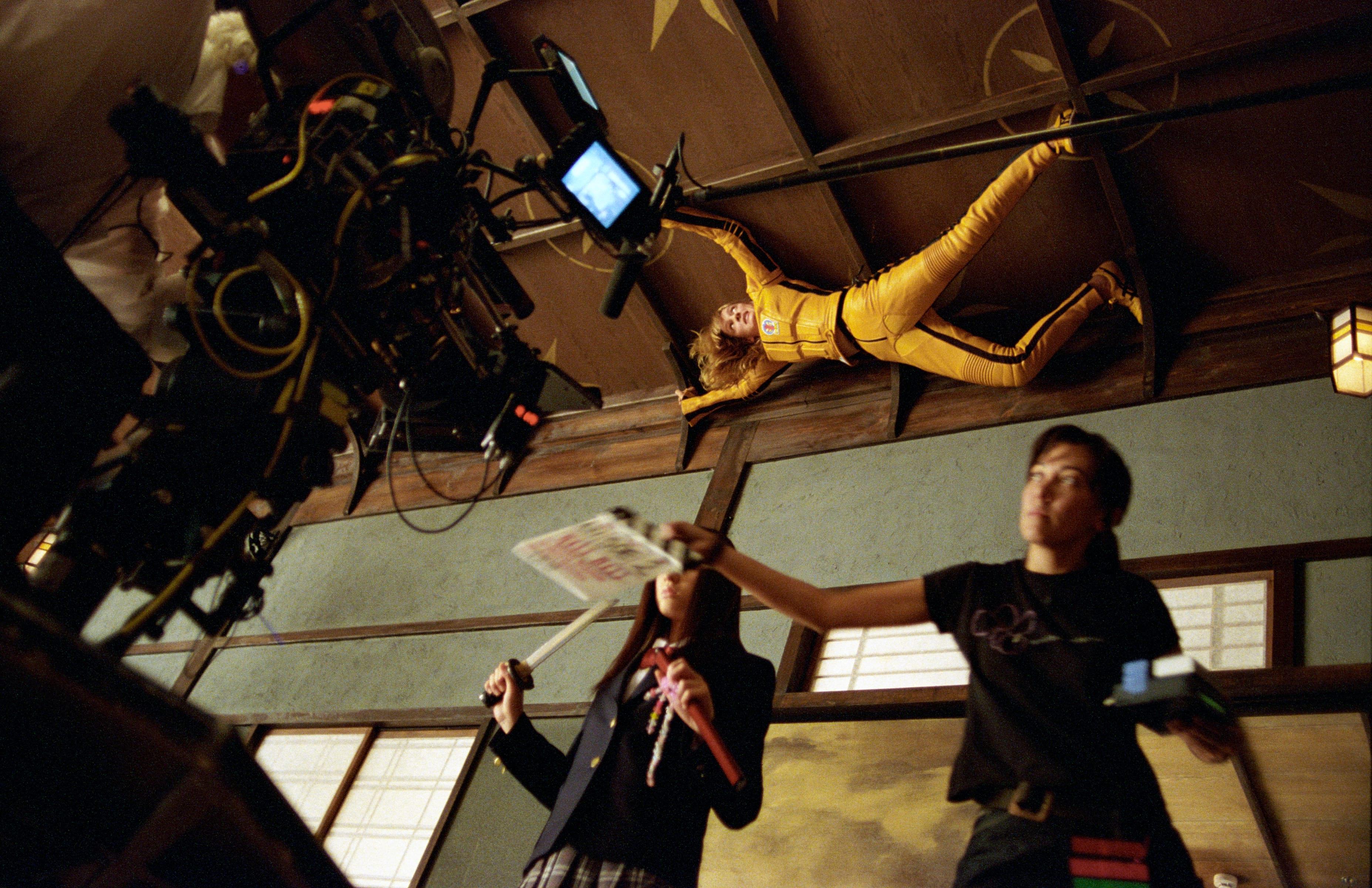

Tarantino devised a complicated traveling shot to initiate the carnage. Starting behind the bandstand, as an all-girl Japanese combo bobs their beehives to a retro beat, Steadicam operator Larry McConkey walks the camera screen right, passing under an exposed stairway, which reveals The Bride descending into frame. The camera swings out from beneath the stairway and follows The Bride as she strides across the room down a side hallway. As she passes into silhouette behind a rice-paper screen, the camera rises and continues to follow from an overhead angle, descending again as she enters the bathroom; the camera then swings to find the House of Blue Leave’s owner and her manager, and the camera leads them back down the hallway onto the main floor, where they ascend a staircase. The camera steps atop a crane and sweeps across the dance floor, past the band, to the opposite staircase, where it cranes in and booms down to reveal Sophie Fatale (Julie Dreyfus), a former member of Bill’s assassin group and soon-to-be victim of The Bride. The camera then follows Sophie into the bathroom, and as she steps up the mirror, the camera continues past her to the wall of a stall. A scrim wall lighting cue reveals The Bride inside, waiting.

Richardson and his crew spent just six hours rehearsing the shot and completed it in one day. “It sounds simple, but it wasn’t,” says Ault. “We needed to see the entire set at the beginning of the shot, so the crane Larry eventually stepped onto couldn’t be there. We had people assigned specific duties to fly ramps in, roll the crane down, move walls out and back. We had to get the crane in while the camera was off doing the other part of the shot.

“We needed a rig for Larry that would elevate him, travel about 20 feet and then descend so he could step off. We ended up using a motorized flying-chair rig that I designed and operated. It acted kind of like a carnival ride for Larry as he watched Uma travel down the hallway from above. Meanwhile, the wall [on the main stage floor] was opened up, the ramps were flown in and the Pegasus crane was prepared for Larry to come back out to.”

The highly portable Pegasus — whose arm allows 360-degree movement and can be built to several different lengths — is one of Richardson’s favorite tools, and Ault carried one throughout the shoot. “Bob is happiest when he’s up on the crane, wrapped around the camera,” Ault remarks. “I think he likes it because when you swing an arm, it’s so fluid; you don’t have to worry about bumps in [dolly] track, and you can gently change elevations. Plus, the longer the arm, the less arc you have in your swing, and it starts to look just like a dolly move. John Toll [ASC] moved an Akela crane over blowing grass magnificently to get that kind of effect in The Thin Red Line”

Ault also describes doing “some fun stuff” with a linear track rig. During one of her many throwdowns, The Bride effortlessly dodges a flying hatchet as it spins through the air, inches away from her nose. Normally such a feat would be created in post with special effects, but given Tarantino’s aversion to all things digital, Ault felt compelled to summon some low-tech inspiration. “Quentin’s a pretty organic guy, but, obviously, we weren’t going to throw hatchets at Uma,” he quips. “To get the shot, we mounted the camera on a linear track, which is a little trolley on twin stainless-steel rods that the grips would push as fast as they could go, about 10 mph. It’s a castered system, so no matter how fast you move it, you don’t have to worry about it coming off. We put a bungee braking system on it, rigged the hatchet in front of the lens and ran it right past Uma’s face. Quentin loved it when we came up with solutions like that.”

Ault also used the track to create a shot in which a wire-aided Thurman runs up a stairway banister. “To get the necessary speed, it had to be filmed with a camera that wasn’t ‘operated,’” he explains. “It’s pretty much a locked-in shot, so we set the linear track up on the same angle as the banister, with pulleys rigged on it so we could move it as fast as a person at a run.”

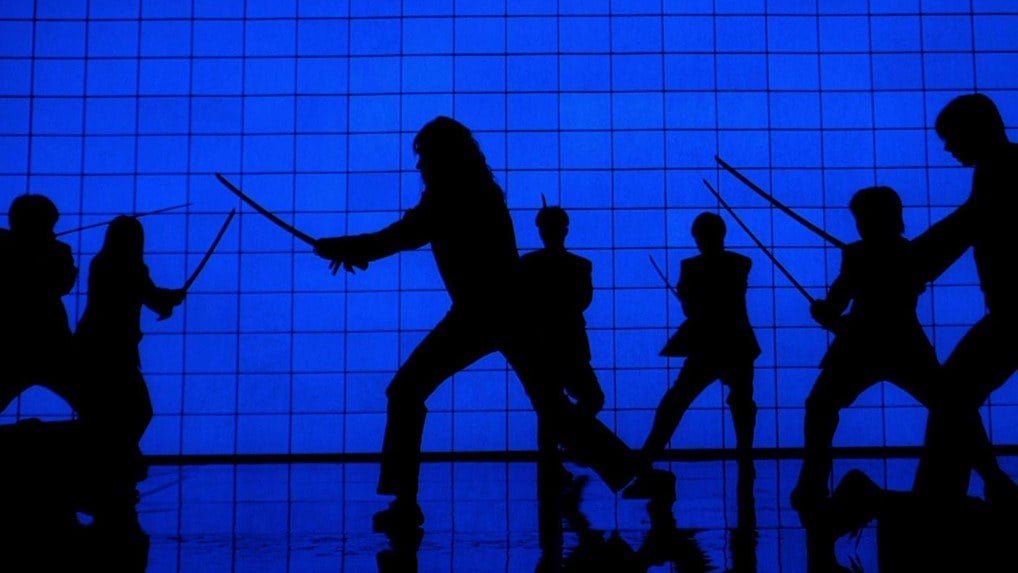

Richardson’s lighting for the sequence is as stylized as the camera movement, mixing scores of practical fixtures — Kincaid rigged more than 300 for the 140' x 80' set — with brash transitions between soft and hard sources. “In this particularly long sequence, the lighting starts soft and moves progressively toward higher contrast levels,” explains Richardson. “As the threat develops and the battling becomes more involved, the style of lighting alters to reflect the graphic nature of the action. The backgrounds drop off and the center arena becomes more prevalent.”

The cinematographer also employed his much-imitated “halo” effect “here and there,” though he prickles at the notion of being pigeonholed. “I’ve actually done two films in a row now with very little use of that style,” he says, referring to the Academy- and ASC Award-nominated Snow Falling On Cedars and The Four Feathers (see AC Oct. ’02). Still, he maintains that his lighting for Kill Bill “is brutal when it needs to be.”

Another distinctive technique Richardson has been honing for several years is what he calls a “psychological” use of dimming cues within shots: “It might be in the slow fading-down of a background, or cross-fading between two different colors. I did this in a scene early in Bringing Out the Dead: Nicolas Cage is reviving the old man in his apartment, and the background shifts down about two stops towards black. It’s extremely subtle. You won’t consciously notice it, and if you do, then I’ve made errors. I’ve been doing this sort of thing for several years and I’ve become progressively better at finessing it.

"In Kill Bill, we didn’t do much motivated lighting in the classic sense,” he adds. “I was more often trying to emphasize a psychological moment in the action. There’s one cue where Uma is about to take on a gang of the Crazy 88 in a samurai battle. The foreground on one stage fades, the colors go through a lighting change, and we reveal a much larger stage where the battle continues in silhouette.”

The strategy also came in handy for lighting the film’s elaborate moving compositions, which Tarantino preferred to shoot in sequence. Kincaid presided over 400 dimming channels and used “a very small remote board that I’d handhold while hiding behind the camera” as it zoomed around the katana-wielding characters. “When you’re walking the camera around people,” he explains, “a backlight will never work as frontlight because it’s usually too steep. You have to dim that down and bring up a different front- and backlight for each new camera position.”

Richardson points out that every dimming cue means a corresponding shift in color temperature. “It’s virtually impossible to get around,” he says. “You can attempt to hide it with certain elements passing through foreground or background, or by passing another light through the frame itself. There are thousands of ways to do it, but it’s actually a far easier task in black-and-white.”

Dimmer boards helped Richardson support Tarantino’s desire to shoot in sequence, but some of the director’s other predilections, such as his fondness for the Hong Kong-style snap zoom, required much more “assimilation” from the cinematographer. “I am not a fan of the zoom,” Richardson says flatly. “It was entertaining for Quentin to have to break me in. He’d say, ‘I got your virginity on this, Bob, and if it hurts, you know what? You’re going to have to learn to enjoy it.’”

Luckily, it didn’t take Richardson long to loosen up. “There was a certain point in the shoot where it just felt great!” he acknowledges with a chuckle. “After that I’d start thinking, ‘Hey, let’s just toss in a snap here, a snap there Sometimes Quentin would come up with a smile on his face and say, ‘Not the right time for it, Bob, but I’m damn glad you’re doing it.’”

Super 35mm (3-perf) 2.35:1

Panavision Platinums Primo lenses

Kodak EXR 100D 5248, EXR 200T 5293, Vision 320T5277, Vision 500T 5279, Vision 800T 5289 and Double-X 5222

Digital Intermediate by Technique

American Cinematographer: What films and filmmakers have most influenced your sense of camera movement?

Robert Richardson, ASC: At this moment in my career, I'm most influenced by Hitchcock's films, primarily because of their precision. It's difficult not to cite Kubrick, of course; the Steadicam work in The Shining is amazing, whether it's following behind the boy in the hotel corridors or leading Jack Nicholson through the maze at the end. Martin Scorsese's films are also a huge influence on me. The camerawork in Raging Bull, especially during Jake LaMotta's final bout with Sugar Ray Leonard, is phenomenal; it's whirling around and around, but the framing stays very precise.

Bernardo Bertolucci is a master of motion. Along with Scorsese's, his work is one of the biggest influences on my career. In The Last Emperor, there's a shot where the sounds from the outside world are coming to Pu Yi from over the huge wall of the Forbidden City; the camera cranes up from to the edge of the wall to "hear" them, and then comes back down. The difficulty of creating those moves and lighting them, which Bertolucci achieved in collaboration with [Vittorio] Storaro [ASC, AIC], are accomplished to an extraordinary degree. I don't know if they've ever been equaled.

The films you've mentioned often feature very overt or elaborate moves. Do you find that kind of camerawork particularly inspiring?

Well, even with the more elaborate ones, it's not so much about 'punching home' a scene through camera motion as it is about being appropriate. Andrei Tarkovsky, for example, is not one to 'punch' anything in his films, but they have incredible visual impact because the camera movement is always extremely appropriate in emphasizing certain psychological moments. My Name Is Ivan has some phenomenal camera motion, with the frame moving in a very deliberate way between the trees [in a flooded forest at night]. I'd call it poetry in motion, and it's remarkable in its artistry. All the filmmakers I've mentioned have very different visual attitudes, but they are all very deliberate about where and why they move the camera.

Has your own sense of how to move the camera changed over the past 20 years?

It has evolved through age, experience and knowledge. The choices I make now are less bound to a sort of 'from the hip' sensibility. I still have the capacity for that kind of work, obviously; Natural Born Killers was not that many years ago. I have no problem with randomness or improvisation, but now I'm much more aware of making those choices — and what they mean — than I was at the earlier stages of my career. — John Pavlus