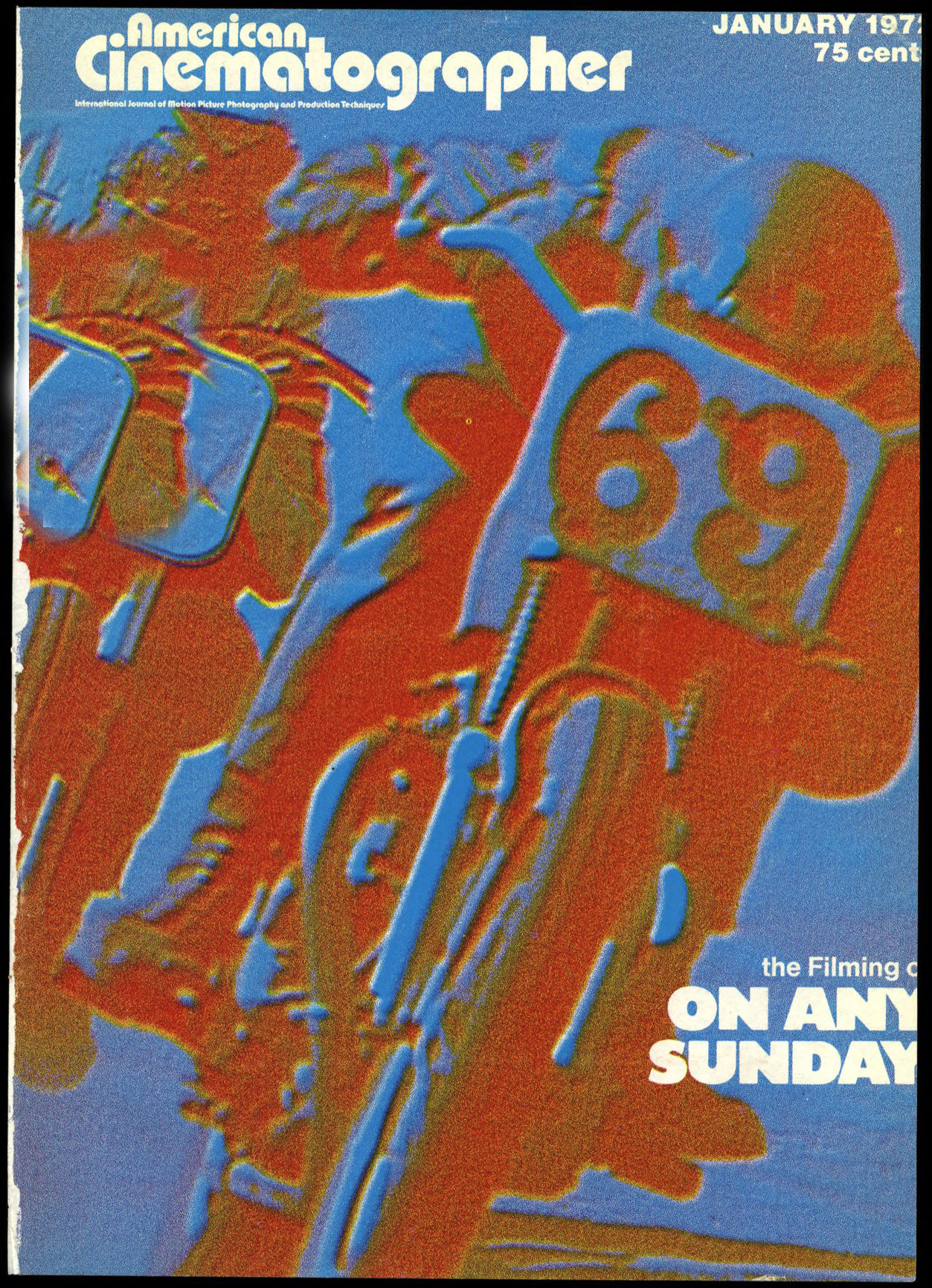

The Last Picture Show: A Study in Black-and-White

Brilliant new director Peter Bogdanovich and veteran cinematographer Robert Surtees, ASC combine talents to create an outstanding film.

"Small-town life in America is not like Our Town," says director Peter Bogdanovich. "Especially in Anarene, Texas in 1951."

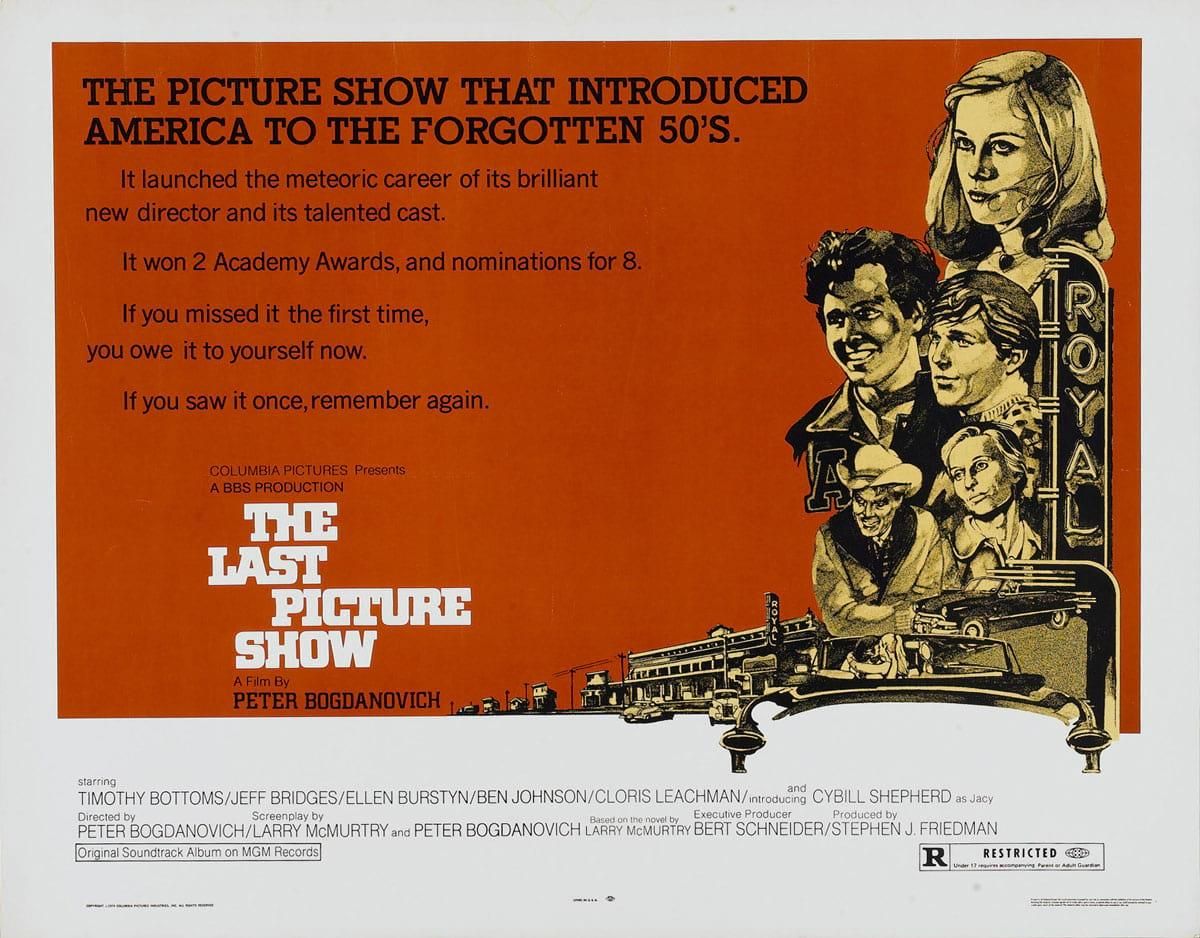

He is referring to his feature film, The Last Picture Show, a BBS Production for Columbia Pictures, which has had the nation's top critics reaching for a whole new batch of superlatives.

It is a film story about growing up in a small town that is running down, where being free means getting out—and it is worthy of the critical raves which are being heaped upon it.

Though Bogdanovich is 31-years-old and, therefore, could not possibly "remember" accurately what small-town America was like in the 1950s, he has somehow managed to capture the atmosphere of the time and place with the utmost precision. There is nothing startling or "far-out" about the film's style. Rather, it may be said to pay homage to the straightforward, superbly crafted, unobtrusive finish characteristic of the "traditional" American films that were a mainstay of entertainment in this country during the period between 1930 and 1950.

For BBS Productions, which has produced a series of poignant contemporary probes — Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces and Drive, He Said — The Last Picture Show represents a departure. But it is a look back, which is less nostalgia than a slice of the way it really was. And filming the way it was meant, capturing the way it looked and the way it felt to be young and vulnerable in a northern Texas town in 1951 and 1952.

To obtain an authentic look, Bogdanovich decided to go to a place that had the atmosphere and feel of the town novelist-screenwriter Larry McMurtry called "Thalia” in his original novel.

Although there was a good deal of initial apprehension from the Anarene "locals" when the film crew arrived, once shooting actually began, the residents assumed a variety of speaking and non-speaking parts, and "the people proved more patient than they had any right to be. We tied the place up for two months!" says Bogdanovich.

So that the non-Texans in the cast would get to know the terrain and speaking patterns, they spent a week on the location before a foot of film was shot, just soaking up the flatlands atmosphere.

I said to him, “Peter, you’re going to be alright. You’re going to be a big director because you’re just stubborn enough to get what you want.”

— Robert Surtees, ASC

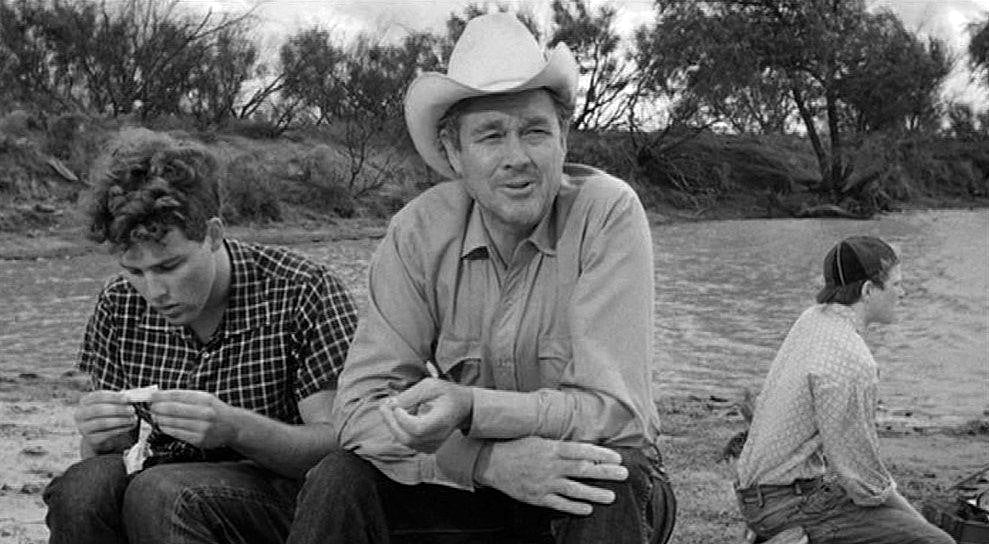

But, like the sets, most of the actors were indigenous: Texans predominate in the supporting parts. Actors from several Texas cities were hired to portray the high-schoolers, cowpokes and grease monkeys of Anarene. Many who came to watch quickly found themselves in front of the cameras, with a spontaneity Bogdanovich insisted on around the set. That kind of flexibility brought some amazing results. Example: Sam Bottoms was selected for the key role of Billy when he arrived to watch his older brother Timothy on the first day of shooting. Example: for the "skinnydipping" party, Bogdanovich picked some local high-schoolers, but feared they might be a little wary about making their film debuts in the altogether.

The way it felt: "When I read McMurtry's book, it touched a very responsive chord. I got very excited by the notion of doing an early 1950s period piece and exploring the change that came with the demise of the small-town movie house and the introduction of television. A whole kind of dream world ended and a lot of other illusions began breaking up," observes Peter Bogdanovich.

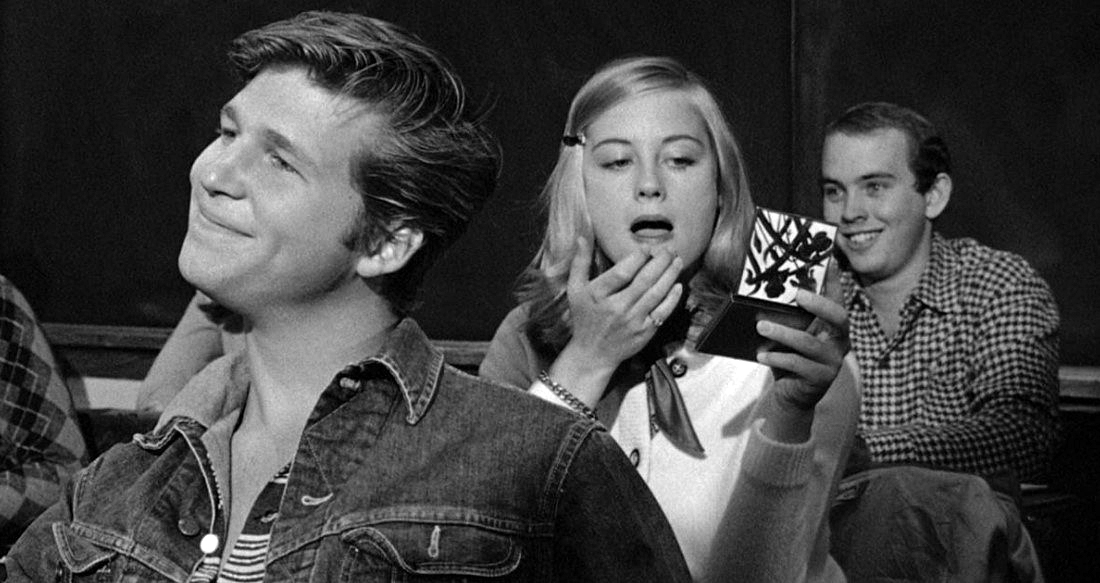

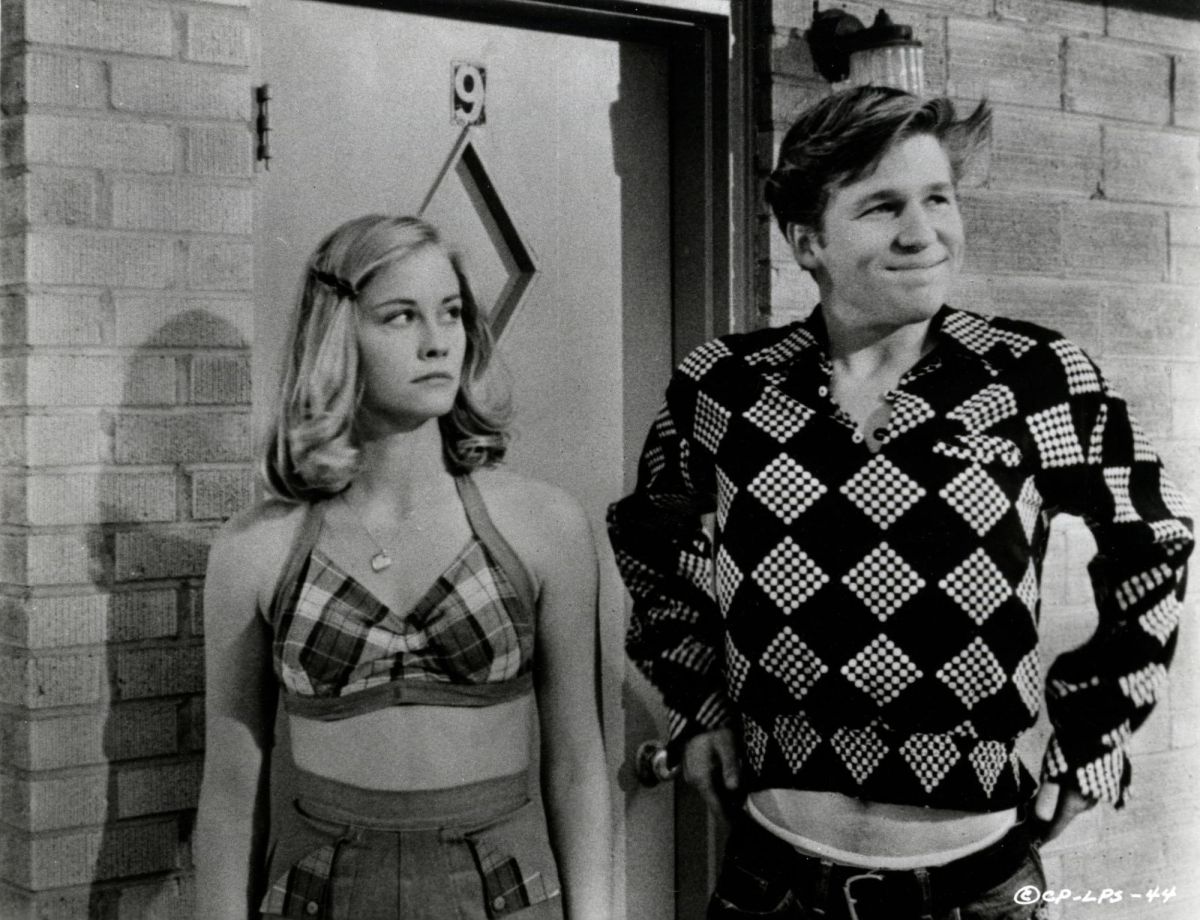

Bogdanovich's aim of capturing the end of an era of dreams and possibilities echoes through all the episodes of the film. The Last Picture Show conveys the onset of age and responsibilities for a generation of kids born during the Depression and raised during World War II. Shot in black-and-white (Bogdanovich: "I thought everything would look too pretty in color") to enhance the gritty, shabby feel of Anarene, The Last Picture Show will be familiar to anyone whose past includes a small town. A cast of talented youngsters — Timothy Bottoms and Jeff Bridges in only their second screen appearance, Cybill Shepherd and a host of supporting players making their debuts — only heightens the freshness of the production and gives off an unmistakable feeling of authenticity.

When Sonny and Duane go to the movies the night the picture show closes, the night before Duane goes off to Korea, they see Howard Hawks' Red River. "I wanted a classic western to close the theatre," says the director, "a picture about Texas when it meant something in an epic sense." The Last Picture Show is an epic about the end of epics.

For the director, the picture is a personal triumph — and deservedly so, for it reflects the talent and skill of a technician who has learned his craft well.

Peter Bogdanovich made his startling directorial debut in 1968 with Targets, the gripping and widely acclaimed study of a sniper. The first American critic turned director, Bogdanovich has authored studies of Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, John Ford, Fritz Lang, Allan Dwan and Orson Welles, and has completed a feature documentary on Ford, Directed By John Ford (AC, November, 1971), which the American Film Institute will release this year. He also worked on a BBC-TV study of Howard Hawks in 1967 and has written countless articles for Esquire, Saturday Evening Post and numerous other periodicals. But the 31-year-old native of New York City says, "I always considered myself a director who was making a living writing about motion pictures, not the other way around."

Bogdanovich served as assistant to the director on Roger Corman's The Wild Angels (1966), also doing a considerable amount of re-writing on the script. He has directed and produced a number of theatrical productions off-Broadway and in summer stock. A genuine scholar of film, Bogdanovich feels his greatest affinity for the work of Ford and Hawks. He is currently directing and producing a comedy for Warner Bros, What's Up Doc?, with Barbra Streisand and Ryan O'Neal.

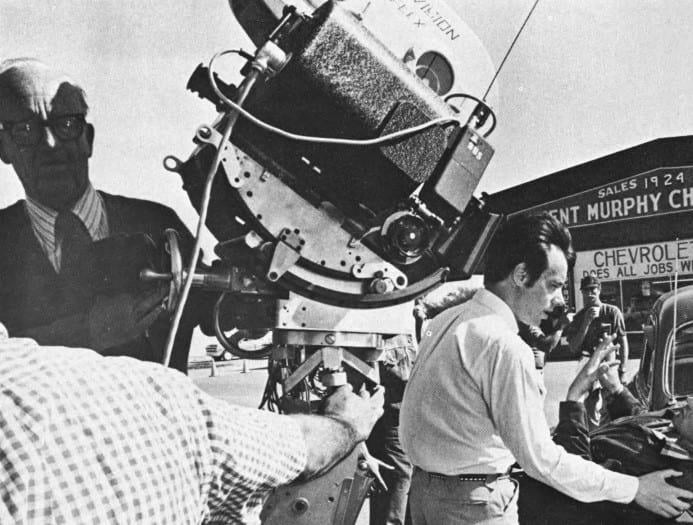

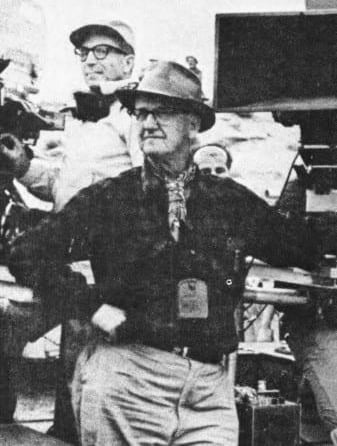

"Bob Surtees is the first cinematographer whose name I remembered as a kid going to the movies," says director Bogdanovich, who played out an old fantasy when he picked Surtees to film The Last Picture Show. At age 11, Bogdanovich went to see King Solomon's Mines with his father, a painter, and remembers his father marveling at the photography of Surtees, who won his first Academy Award (Best Color Photography) for the film in 1950. Looking for a cinematographer familiar with black-and-white, Bogdanovich chose Surtees after hearing a glowing recommendation from Mike Nichols, for whom Surtees shot The Graduate.

of photography Surtees likes working with new directors — those who have talent, that is.

Born in Covington, Kentucky, in 1906, Surtees' distinguished career includes The Bad and the Beautiful (Academy Award in 1952), Ben-Hur (Academy Award in 1959), Intruder in the Dust, Mogambo, Oklahoma, and Doctor Dolittle, among many others.

In the following candid interview, Surtees, a veteran cinematographer with a degree of verve, enthusiasm, and imagination surpassing that of most of the younger technicians in the industry, discusses the unique challenges and satisfactions of photographing The Last Picture Show:

American Cinematographer: I'd like to ask first, how it came about that The Last Picture Show was photographed in black-and-white instead of in color.

Robert Surtees, ASC: That's the question I'm asked most often. It's generally understood in the industry that it's harder to sell a black-and-white picture to TV later on, because all features are shot in color now. They're afraid that TV viewers, seeing a relatively new picture on the tube, in black-and-white, will think something's gone wrong with their receivers. The idea of shooting in black-and-white came from the director, Peter Bogdanovich. He had become well-known as a film critic — the only American critic who liked American pictures — and also as a film historian, and had studied the styles of all of the outstanding films of the past. He is a great admirer of John Ford and Orson Welles, technically speaking, and has written books about both of them. He especially liked Citizen Kane and in our preliminary meetings, before I was definitely assigned to the picture, he asked what I thought about shooting his picture in black-and-white. Naturally, I said it would be great. It would be a change. Gosh, I don't know how many years it's been since I've done a black-and-white picture.

How did you arrive at the distinctive photographic style used in the film?

Basically, what we did was go back and use some of the techniques of Orson Welles — but not as extreme, because we were shooting in all real interiors and on a very small budget. It takes a huge amount of foot candles to get extreme depth of field shots indoors and we had neither the room in our "sets" nor the budget to accommodate a lot of big lighting units. As for style, Bogdanovich and I arrived at the idea that the photography should look as if it had been done by an experienced amateur who had a camera he could hold awfully steady and who liked to drop in on people and photograph them. This meant getting away from certain things we've done photographically in every picture over the years — things like lighting a wall so that streaks of shadow fall onto it. Instead, I decided to light the walls with soft, flat light. As it was, we had to put most of our lighting units on the floor and hide them everywhere in the actual interiors.

What kind of shooting schedule did you have?

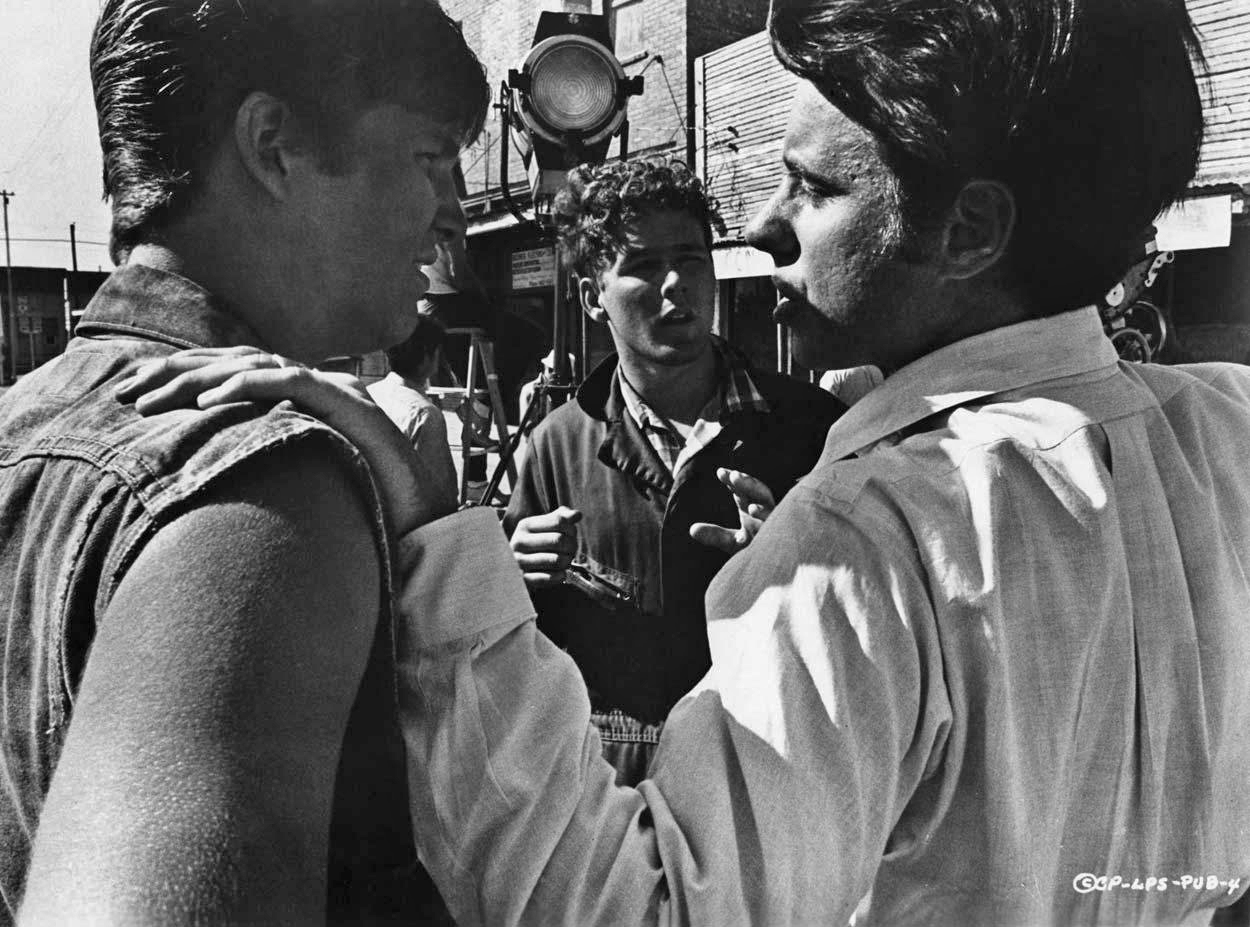

Eight weeks — which is like working at the speed of a quickie compared to the expensive features that are made, but we had to work that fast because of the amount of money available. Then, too, it was really Peter's first feature — although he had made one previous low-budget feature on his own, which wasn't a success — and he had to figure things out, which takes a bit more time than usual, also. I will say that he's one of the brightest guys I've ever known. I worked with Mike Nichols on The Graduate and I'd rate this fellow right up there with him. Mike is an effervescent sort of man, while Peter is much more serious. He's colder, too. He realized this and he fought it.

In what ways do Bogdanovich's methods differ from that of other directors you've worked with?

Well, for one thing, he doesn't shoot master scenes. He does each bit of the action separately and picks the next cut up from there. For example, there is one sequence in which two boys go all the way around a car pushing and arguing and it ends up with one boy getting hit with a beer bottle. It's a short sequence — it couldn't have run much more than 200 feet in the final editing — but it was made up of 34 separate cuts. At the time, I wasn't quite sure how well it would go together, but he put it together and it works beautifully. I wouldn't recommend that every director try that, however. Of course, Bogdanovich does all of his own editing — even the routine things that an assistant editor would ordinarily do. He works without an editor in the belief that, if you have another man involved, and even if you are working right over his shoulder, it will affect the final result. He has a point there. In the sequence I just mentioned, for example, unless you were Peter Bogdanovich, you wouldn't know how to put it together.

It appears that you enjoy working with new young directors.

Those fellows amaze me — the ones that are good, that is. Mike Nichols, when I worked with him, was 32 and Peter was 29 when we started his picture. But neither one of them were young guys who were just starting out. Mike had proved himself to be probably the best director in New York on five plays before making his first film, so he wasn't some kid walking the sidewalks who suddenly jumped into being a director. The same is true of Bogdanovich. He'd had so much contact with films, motion-picture history and the work of various directors, that it gave him considerable background. I was afraid, at first, that he might become too mechanical — like doing a John Ford thing today and an Orson Welles thing tomorrow — but that wasn't true, actually. He changed things considerably and came up with his own style.

From the cinematographer's standpoint, which do you think is more difficult to shoot — black-and-white or color?

From the technical standpoint, I still insist that black-and-white is much more difficult than color. For example, in an actual interior, if you pan from a well-lighted figure to an area that is dark but too cramped to place lights where you really want them, you can just flatten that area out and get by. But in black-and-white, if you want a shadow, you've got to put it there, man. You can't depend upon fill light to take care of it. You really have to model the subject with light instead of counting on the colors for separation. Of course, the right makeup, wardrobe, and sets become more important in color. You can sometimes get by with the wrong makeup in black-and-white and you can help a bad set. You can use smaller lamps and get in behind chairs and break up walls by putting shadows on them. But, on the other hand, in shooting black-and-white, you have to do it. You can't count on the process you're using to do it for you.

What reactions have you received regarding the use of black-and-white for this picture?

I've heard a few comments. Either people like the photography very much or they don't like it at all. One reviewer said that it didn't have anything like Hud in it. Jimmy Wong Howe [ASC] photographed Hud and it was beautiful. But The Last Picture Show couldn't be beautiful. That kind of photography would have been all wrong for this picture.

Could you comment a bit more on your use of extreme depth-of-field in this picture?

When Gregg Toland photographed Citizen Kane, the style called for a really exaggerated depth of field, which meant stopping the lens down as far as possible and using a tremendous amount of light. In order to stop down that far, he resorted to something that had been done in the old days of photography. He had the irises removed from his lenses and replaced with slides that had very small holes drilled in them — something like the mattes used in the Spectra exposure meter to adjust for ASA ratings. Well, we didn't go that far. But I shot almost all of the picture, including the interiors, at f/8, occasionally stopping down to f/10. That still required a heck of a lot of light by today's standards — 600 foot candles at f/10.

What film stock were you using?

Outside I used Eastman Plus-X negative. It's rated at ASA 80, but l had plenty of light for the stop I needed. Inside I used Double-X. It has more grain but is rated at ASA 250 and can be pushed almost to ASA 1500, if necessary.

Did you push any of it?

No. It was so fast that I didn't have to. I could have gotten better quality by using the Plus-X indoors, as well, but that would have required even more light and, in this picture, the quality wasn't as important as having it look real.

Aside from the sheer necessity of having enough light, what would you say was your greatest problem in achieving the extreme depth-of-field effect.

Maintaining the proper balance between key and fill light. In color, for example, all that the film can handle is a ratio of about 10-to-1 between the brightest object and the darkest object, and, on night exteriors, you usually light at about 4-to-1. But black-and-white film can accommodate a brightness contrast ratio of about 100-to-1, which is completely different from color and much more dangerous. Let's say that you shoot a scene at a certain ratio and you want to stop down further for the very next scene. As you stop down, you automatically pick up contrast — so you have to figure out just how much extra fill to add for compensation in order to get the second scene to look like the first. It can be very tricky, especially if you've been shooting nothing but color for a good many years.

Your exteriors had a dark, brooding quality and very rich skies, which indicates that you must have made extensive use of filtration. Isn't that so?

Yes. I went back to the old black-and-white Western type of photography, which isn't done anymore, where you have 20 or 30 filters that you use for different types of scenes, as called for. To say how and where you use each filter would be misleading because you could give the same set of filters to a different cinematographer and they would get a different result. In using filters, you sometimes under-expose or over-expose on purpose to get a particular effect. You might use heavy contrast filters, even as high as a 25 red or 21 orange, in your tong shots to make the sky darker — but this also corrects everything else in the scene. The whites become whiter; the darks become darker. When you move in for the closeups, it's a good idea to change to something like the old Aero-2 filter, which gives you more control. Or, if you still have to use the heavy-contrast red or orange filter, you balance the lighting by eye through the camera. When you look up it doesn't look like you've got any light on the subject at all, but you're photographing what you see through the filter. If you're stuck with using a red filter in a closeup, the face will go chalky where the sun hits it — so, by artificially lighting it, you work it over so that it doesn't look chalky. You knock down the sunlight by putting a net up to shade the face and you balance your light by looking through the camera. I think that one of the reasons I was asked to photograph this picture is because not many people shoot in black-and-white anymore and I'm one of the few leftovers from the old black-and-white days. You know, what they need now is 21-year-old cinematographer who has 60 years of experience.

There's no way for them to gain that black-and-white experience anymore, is there?

No — that's the trouble. All that experience is gone. I hate to see black-and-white go completely. I think we've lost a great tool, because it's absolutely right for certain types of stories. It's like the difference between a painting and an etching. The work that Arthur Miller [ASC] used to do in black-and-white, for example — it was like an etching. Just beautiful art. It's simply not possible to get the same kind of halftones in color that you can in black-and-white.

Can you tell me a bit about the lighting units you used on this picture?

As I've said, we were going for depth of field on the interiors and often had the lens stopped down to f/10. What you need at that aperture is a flashbulb! For the 600 foot-candle key required in many of our scenes we couldn't very well get by with quartz lights, although I did sometimes use them to fill in for night stuff. My main objection to quartz lights, except for fill, is that I have no control over them. I can't get them to cast a sharp shadow. Even so, we kept the lighting equipment to a minimum. We had only two arcs, whereas on a picture of this size you'd ordinarily use at least five. We'd light up the whole town with just two or three lamps. Of course, they weren't interested in having the backgrounds brightly lighted. I made a test in advance to show them what they were going to get, so they fully understood what the result would be. We made trucking shots down the main street at night with no camera car. We had to use a station wagon — but it worked out.

It would appear that some of those actual interior locations were so small that you'd have trouble getting large lighting units into them — let alone a camera, crew and actors.

I found that I could use the smaller studio-type lights if I could get them close enough to the people. The only time we used the arcs on interiors was for an effect, a shaft of light coming through a window or something like that. We did a lot with a few units, just as Jack Marta [ASC] used to do when he was photographing the Route 66 TV series some years ago. He traveled all over and just plugged his few lights into the line current. He did a tremendous job, as good a job as I've ever seen on interiors, and with so little equipment. One of my problems was that this director liked to do 360-degree scenes, where the actors walked all around the place with the camera following. We never stopped moving throughout the whole picture. Such scenes are a cinch if you can do them in a series of cuts, but a continuous pan is something else. We were always hiding lamps behind furniture and on the floor. We used all kinds of gadgets, like suction cups to hang baby spots on a wall. When you get it all lined up, you're still not sure whether you're going to make it. The only thing that keeps you going in situations like this is how many years you've been in the business. Actually, I've never seen a shot that couldn't be made — if you have sufficient time to do it.

The photography in this picture is very clean — that is, free of trimmings and frills. Is that due to the fact that you had such a small amount of lighting equipment available?

Not really. I don't use backlight anymore — unless it's established as coming from a practical lamp or something like that — and I don't break up the walls with shadow patterns. I think that's old-fashioned and "motion-picturish" and it would have been all wrong for this type of story. Now, if you were shooting a glamour picture, it would be different. You'd tend to go back to the old style, with all the trimmings.

What kind of power source did you use to run your lights?

I had one little generator to carry the full load and the only trouble we had, from time to time, was overloading the generator, We kept the generator on the bus we traveled in and once it set the bus on fire. That bus was used to move the entire company around. There were no separate cars. The director and the actors all piled into the bus with the crew and it was sort of fun. There was a great spirit on this picture, we were considerably undermanned and everybody did as much as they could to help one another.

What kind of lenses did you use on the picture?

The entire picture was photographed with one lens — a 28mm. We used it for every shot, although it did cause something of a sound problem with camera noise when we would move in for the closeups.

I can't remember seeing anything that looked like a zoom shot in the picture. Did you use a zoom at all?

Bogdanovich won't even allow a zoom lens on the set. He detests zooms, even when they're used just to follow someone. Orson Welles had told him that a zoom creates artificial movement and, technically, he's correct. A zoom shot is merely a magnification of an object. It doesn't give you at all the same perspective as you'd get, for example, if you dollied through a doorway. However, there were many times when it was necessary to move the camera just a couple of feet to tighten up the composition during a shot. Using the zoom for this purpose would have saved literally days on the picture, but Peter would insist on laying track and dollying that couple of feet. He has his integrity — which is very important to him—and you have to respect him for it.

There are various degrees of closeness in the director-cinematographer relationship. Just how closely did you and Bogdanovich work together on this film?

Very closely. There's a great deal of person-to-person contact when you're working with him. You're with him all the time. You're with him at dinner and after dinner and you never stop talking about the picture. He asks for your opinions — not just on the photography, but on story points, too. And he makes changes according to what people suggest — if he thinks they're right. If he doesn't think they're right, he always has a lucid reason why not. But I'd say he's very much open to suggestions — except on the subject of the zoom lens. It's fun to talk with him because he's an expert on the history of the film industry. He told me that when he was 11 or 12, his father — who was an artist — took him to see King Solomon's Mines and he said that from that day he remembered the name Surtees and swore that some day he'd make a picture with me. He's probably cured now.

And how about you?

As I said, I like working with new directors, if they have talent — and he's really talented. I said to him, "Peter, you're going to be all right. You're going to be a big director because you're just stubborn enough to get what you want." I said that because I couldn't talk him out of anything, and I'm pretty good at talking directors out of things once in a while. I'd say, "Peter, how can we get that shot? It's impossible to walk around with the camera like that. Where will I put the lights?" He'd say, "You'll get it." And then he'd walk away. And, by God, I'd manage to get it and he'd have what he wanted. I'd just shake my head and say, "You win again!"

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.