Leadership and Artistry: John Lindley, ASC

The ASC honors the cinematographer with its Presidents Award for service to the Society and the filmmaking industry.

When ASC President Stephen Lighthill called John Lindley, ASC to tell him that he would receive this year’s ASC Presidents Award, Lindley tried to talk him out of it. “I thought there had to be someone more deserving than me,” he says.

Lighthill was having none of it. “John’s leadership [as President of the International Cinematographers Guild, IATSE Local 600] through two years of the Covid-19 pandemic, which was the biggest crisis the Local faced since its inception, was remarkable enough,” Lighthill told AC. “However, in the process of resolving the 2021 negotiations with producers and communicating details of the collective bargaining agreement to ASC members, John was diplomatic, informed, generous and calm. John [navigated] a flawed process with great energy and gave comprehensive explanations at a time of great upset. His graciousness led us all by example at a most difficult moment in time.” Lighthill adds that the complications of working under new protocols during the ongoing health crisis, and the tragic on-set shooting death of Halyna Hutchins, ASC also contributed to a difficult public mood.

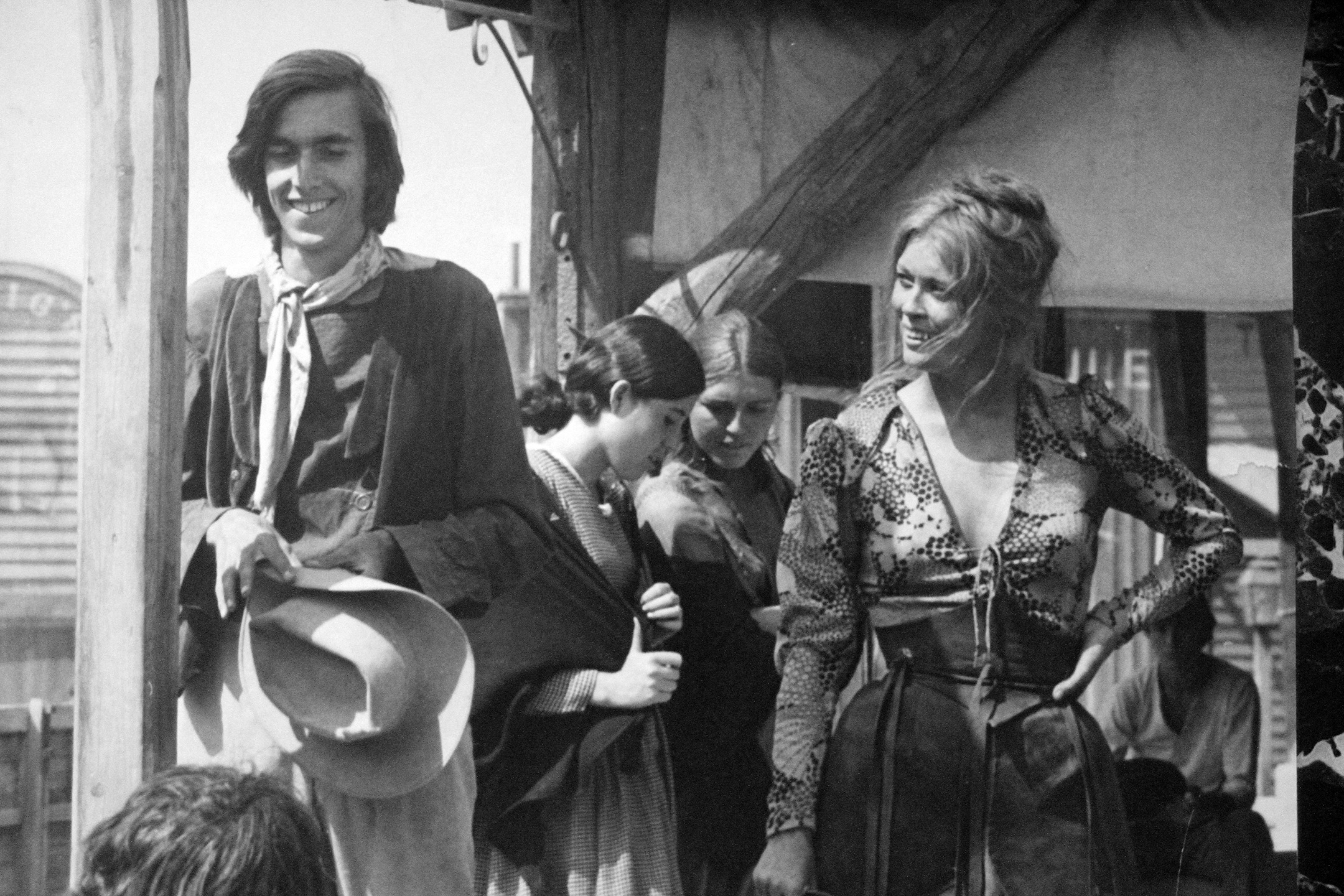

As a youth growing up in New York City, Lindley was precocious, picking up still photography at age 11 and landing a production-assistant job on a feature straight out of high school — with the aid of his mother, a literary agent, who knew the filmmaking couple Frank and Eleanor Perry. That film was the Frank Perry-directed Doc, a Western shot in Spain. “I wanted to work on films from then on,” Lindley recalls.

Lindley went on to attend NYU’s film school, after which he worked briefly as a camera assistant and gaffer until he landed work on the BBC’s freelance New York crew as an assistant. When the crew’s cinematographer left the business — “to restore a water-driven cider mill in Upstate New York,” Lindley says — the young filmmaker stepped into his shoes.

Lindley’s first big career milestone came in 1989 with the baseball fantasy drama Field of Dreams, now in the National Film Registry. “When director [Phil Alden Robinson] called me about working on the movie, I was fearful,” he says, because the book upon which the movie is based, Shoeless Joe, “had an element that was more reminiscent of a horror film than a fanciful drama.” He recalls the idea of “ghosts coming out of cornfields” bringing to mind the popular frightener Children of the Corn (shot by João Fernandes, aka Raoul Lomas) that had come out a few years earlier. “So, I was nervous. But the director, who also wrote the adapted screenplay, is a brilliant writer and managed to translate that book into a movie that I thought would find an audience. I didn’t think that decades later, people would be using lines of dialogue that have entered the lexicon.”

During the shoot, he says, “There were things I didn’t anticipate. For instance, at the end of the movie, before James Earl Jones [who plays reclusive writer Terrence Mann] walks into the cornfield, which acts as a portal to the afterlife, he first sticks his arm into the corn to feel it — and he laughs. [This improvised moment] undoes any of the morbid ghostly questions, ‘Is that the realm of death?’”

Lindley remembers driving back to the hotel with Robinson throughout the first week of production, always during sunset. “I said, ‘You know, we’re missing the best part of the day here. Can we do something about that?’ From then on, there were certain scenes that we shot over a period of sunsets. I really appreciated his willingness to adapt to the beautiful light.” The cinematographer adds with a laugh, “Then, some years later, an ASC member said to me, ‘I really liked the movie and I thought it looked good, but there was 20 percent too much magic hour.’”

Lindley adds, “Another friend said years later, ‘You’ve achieved the pinnacle of success in the film industry.’ I said, ‘Really? What’s that?’ ‘They’re selling your movie at McDonald’s when you buy a meal.’ Field of Dreams was one of a few movies on VHS that McDonald’s sold for some promotional thing. That’s a badge of honor!”

Field of Dreams led Lindley to a decade flush with features, including Sleeping With the Enemy, Father of the Bride, Sneakers and Money Train. That decade was capped off by Pleasantville, now recognized as the first major feature to go through the digital-intermediate process.

The movie is about two 1990s teenage siblings trapped in a 1950s sitcom. The sitcom world starts off with a black-and-white palette, but under the teens’ influence, color gradually creeps in. Lindley was eager to work on the film because black-and-white features were rare at the time. We tested the idea of colorizing black-and-white film, but “there were very few black-and-white stocks available,” Lindley says. “[They] were older stocks that had boulder grain and didn’t lend themselves to visual effects.” In comparison, he adds, “The color stocks had converted to T-grain, which had multiple layers in each color, so the resolution was quite sharp.”

The filmmakers, therefore, shot on color stock, and every black-and-white shot that included color elements was a digital visual effect. Production bought “many computers operated by a legion of people” to strip out color, Lindley says — and then, for the many shots that required it, add color back in for selected elements within the frame. “We had a ‘roto army’ at SGI workstations. It was a ton of work for that team of people. What took a year in the late ’90s, you could do now in a week or 10 days with one colorist.”

Beyond being a technical milestone, Pleasantville stands the test of time as a story. “It’s about something, as is Field of Dreams,” the cinematographer says. “Pleasantville is about change and people’s fear of change. That’s what it relies on for longevity.”

Regarding technology, Lindley describes himself as “an early and enthusiastic adopter. It reminds me of the way I go skiing — really badly, but aggressively!” He bought one of the first Red cameras and a first generation of the Arri Alexa. “I like all types of cameras, and I always have,” he says.

Lindley was invited into Society membership in June 1999, with recommendations from ASC members Steven Poster, Sandi Sissel and Sol Negrin.

The 2010s brought a transition for Lindley — to episodic series, starting with the pilot for the ABC period drama Pan Am, which earned Lindley both Emmy and ASC Award nominations. Pan Am director Thomas Schlamme then invited him to shoot the pilot and several episodes of the WGN America period drama Manhattan, about the Manhattan Project and the development of the atomic bomb. Lindley won an ASC Award for the pilot, and the series remains one of the cinematographer’s favorites. “I liked the material, and I liked the show,” he says. “It’s got a nice period look. We shot in New Mexico, where there’s always dust in the air and it’s always windy. I thought that atmosphere was a great element in the show itself. When you take these people from ivory-tower academic institutions and stick them out in the desert where they’re uncomfortable, it’s a premise that’s automatically going to create good conflict.”

Many series followed, including Unbelievable, Manhunt, Hunters, Your Honor, The Woman in the House Across the Street From the Girl in the Window, Divorce, Snowfall, Castle Rock, and the upcoming Showtime drama Coercion.

Pondering whether there’s any genre he’d still like to try, Lindley says, “I’ve worked in a lot of genres and have good feelings about all of them. But I’d love to go back to shooting documentaries again, and I would direct my own. What I love now are the formats; length doesn’t mean anything anymore. You look at some of the New York Times: Op-Docs, and they’re incredible. I think right now is the golden age of documentary.”

Pleasantville also marked a critical turning point in another aspect of Lindley’s life, motivating his decades-long fight for safe work hours. Brent Hershman, who served as 2nd AC on Pleasantville, died when he fell asleep behind the wheel and crashed into a utility pole, after a 19-hour day on the movie’s set that followed multiple long days in a row. Lindley and gaffer Bruce McCleery (now ASC), coauthored Brent’s Rule, a petition to cap the workday at 14 hours, and the initiative garnered 10,000 signatures. “It got a lot of attention, but did not result in a change of behavior,” he notes.

“John’s graciousness led us all by example at a most difficult moment in time.”

— Stephen Lighthill, ASC

Frustrated by this inaction, Lindley joined the national executive board of the Local 600. “Being a board member was valuable for learning the structure and the way policy is formed,” he says. “But I felt like an extra and I wanted a speaking part. So I ran for vice president, which gave me a speaking platform. But then I realized that the presidency is where you can be really effective and have the broadest reach — and that’s why I ended up running for president. It was in that role that I had the biggest influence in negotiating for the Basic Agreement.”

Lindley is precise about language. “I like to call it ‘unsafe’ hours rather than ‘long’ hours. Some people might want long hours, but it’s hard to find anyone who would advocate for unsafe hours.”

Last fall, after IATSE voted to approve a strike, the labor union and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) reached an agreement that contained progress on the safety front: a mandatory 10-hour rest period without the exemptions for pilots and first seasons that were contained in the 2018 contract. “That is where a lot of unsafe hours occur,” Lindley says. In addition, the 2021 agreement included a weekend turnaround [i.e., time off] — of 54 hours — for the first time ever. “Getting a weekend turnaround was a giant breakthrough,” he says. “Right now, if that weekend turnaround is invaded, there’s a penalty of straight time for invaded hours when returning to work,” so crewmembers are paid an extra hourly rate for every hour that invades the 54-hour weekend turnaround, in addition to their standard pay for those hours. “I would like to see that penalty increased to make it even more undesirable to invade the weekend turnaround.

Under Lindley’s tenure, Local 600 also introduced a pilot initiative to fund “rides and rooms.” Lindley explains, “If a production doesn’t fulfill its obligations, a member who feels it would be unsafe to drive their vehicle home just gets a ride or takes a [motel or hotel] room. The Local will reimburse that person and then make a claim against the producing company to get reimbursed.

Moving forward, Lindley sees a lot of priorities he’d like to address. “There’s a bunch of stuff on my list,” he says. “I’d like the workweek to reset [to straight-time hours] only after a day off; currently it doesn’t. Right now, you can work seven days a week and start the new workweek in straight time. I’d like to see the meal penalties increase to force meal breaks on productions.” And given the continuing deaths and unreported near-deaths on film sets, “we’re overdue for a safety supervisor on the sets. They exist in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. We’re not inventing something. We just need to adopt a system that already exists.” (See AC’s coverage of set safety officers, AC May 2022)

But all of these initiatives will have to wait for different leadership since Lindley is not running for a second term. “I still shoot. I still have a career,” he says. “And I think it’s time for someone younger than me to take up that work and advance it further. It’s a difficult, complex job that takes a while to learn, and somebody with a longer runway should do it. I hope that’s what happens.

While introducing Lindley at the ASC Awards ceremony on March 20, Amelia Vincent, ASC lauded his encouragement of the Society’s Future Practices Committee to collaborate with Local 600 as the industry navigated a safe return to work amid the Covid-19 pandemic — which fostered “a newfound connection and alliance,” she said. Vincent described Lindley as “my own beloved mentor in life and on set,” and expressed her admiration that his extensive work with the guild “is in addition to his real job as a brilliant cinematographer. John’s exquisite eye brings humble beauty and intelligence to every actor who has stood before his camera. He is a director’s partner beyond measure, and he is also the father of three incredible adult children. Somehow he generously finds enough paternal instinct and energy to extend his strength and wisdom to all on his crew.”

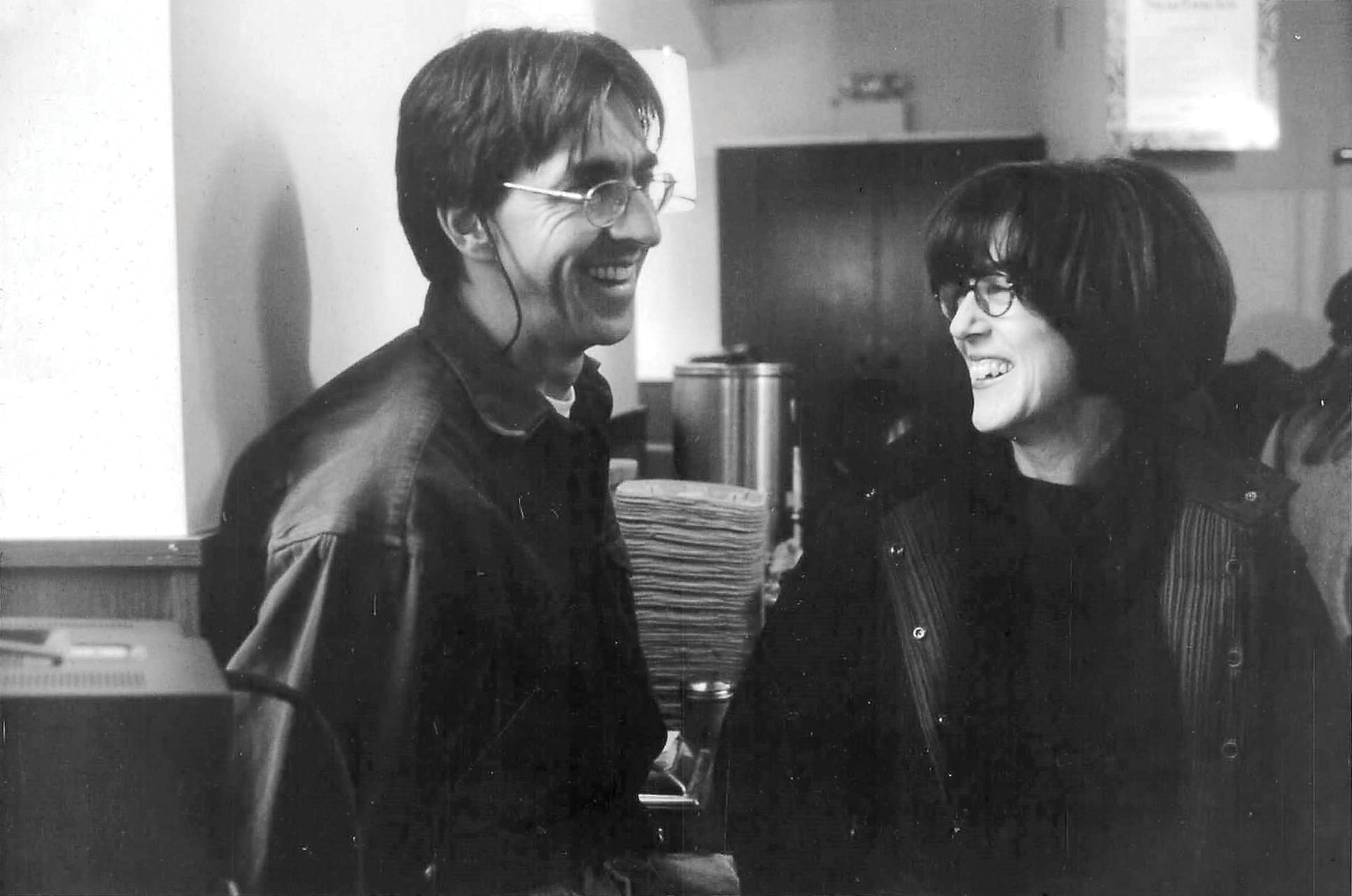

with actor Bill Murray for the 2014 feature St. Vincent.

Lindley’s colleague Rebecca Rhine, national executive director of Local 600, is effusive in her praise about Lindley’s leadership and temperament. “John is an amazing leader,” she says. ”Not just because people trust him, which they do. Not just because he has a clear vision, which he does. Not just because he is compassionate, smart and strategic, which he is. But because John is able to inspire others to work harder, think bigger, reach further than they would otherwise. His unwavering commitment to safety on set, his unquestionable integrity, and his staggering work ethic have forever altered the International Cinematographers Guild in ways that will become clearer as time passes. His clarity and calm through the pandemic, through the tragic death of Halyna, through the most intense round of bargaining in our history allowed the rest of us to breathe and believe we would emerge intact, and now we have. That is a remarkable accomplishment.

Regarding his ASC honor, Lindley says, “When I first moved to L.A. and somebody invited me to the Clubhouse as a guest, I was just awestruck. I remember being introduced around and hearing, ‘This is so-and-so. He invented the zoom lens.’ I just couldn’t believe it.” He continues, “To be given an award by this organization of elite cinematographers is a little hard to quantify. I’m flattered and humbled.”