Lighting for LED Stages

It’s essential that directors of photography who delve into this milieu become familiar with its methods of illumination.

Unreal production-test photos courtesy of Epic Games. ASC Master Class photos by Alex Lopez, courtesy of the ASC.

The introduction of LED walls into the virtual-production landscape has opened up a new world of lighting possibilities, empowering cinematographers to continue to do what they do best: leverage technology to create images that serve the story. As the art of lighting is just as vital in an interactive LED environment as it is in traditional cinematography, it’s essential that directors of photography who delve into this milieu become familiar with its methods of illumination.

There are numerous types of LED-wall systems, from a single standalone-style wall setup to a full mixed-reality (XR) stage with 3D-tracking volume, and many variations in between. Working with these different configurations requires different techniques and creates different results.

The fundamental premise is that the images appearing on these walls are displayed via LED panels, which create varying degrees of emissive lighting, while additional lighting on actors and physical objects can come from LED ceilings or sidewalls, practical lights, and movie lights. Combining these tools can deliver highly realistic results.

In a standalone-style LED-screen environment, the primary screen’s content can be synchronized with other, off-camera LED screens to create additional reflections and interactive lighting effects. Also able to be synced with the system is “kinetic lighting” — via the Digital Multiplex (DMX) network protocol — which can imitate the lighting effects of the content that appears in-camera. (For example, when a streetlight passes by in the background footage on the screen, a lighting instrument can perfectly match its hue and intensity.)

The DMX control in such a setup can be driven either by “pixel mapping” or by manually programming specific patterns or effects; these options would be accomplished with, respectively, pixel-mapping software or a dimmer board. Pixel mapping is a process that samples the hue and intensity of the source footage and then, via DMX, sends those values to the lights.

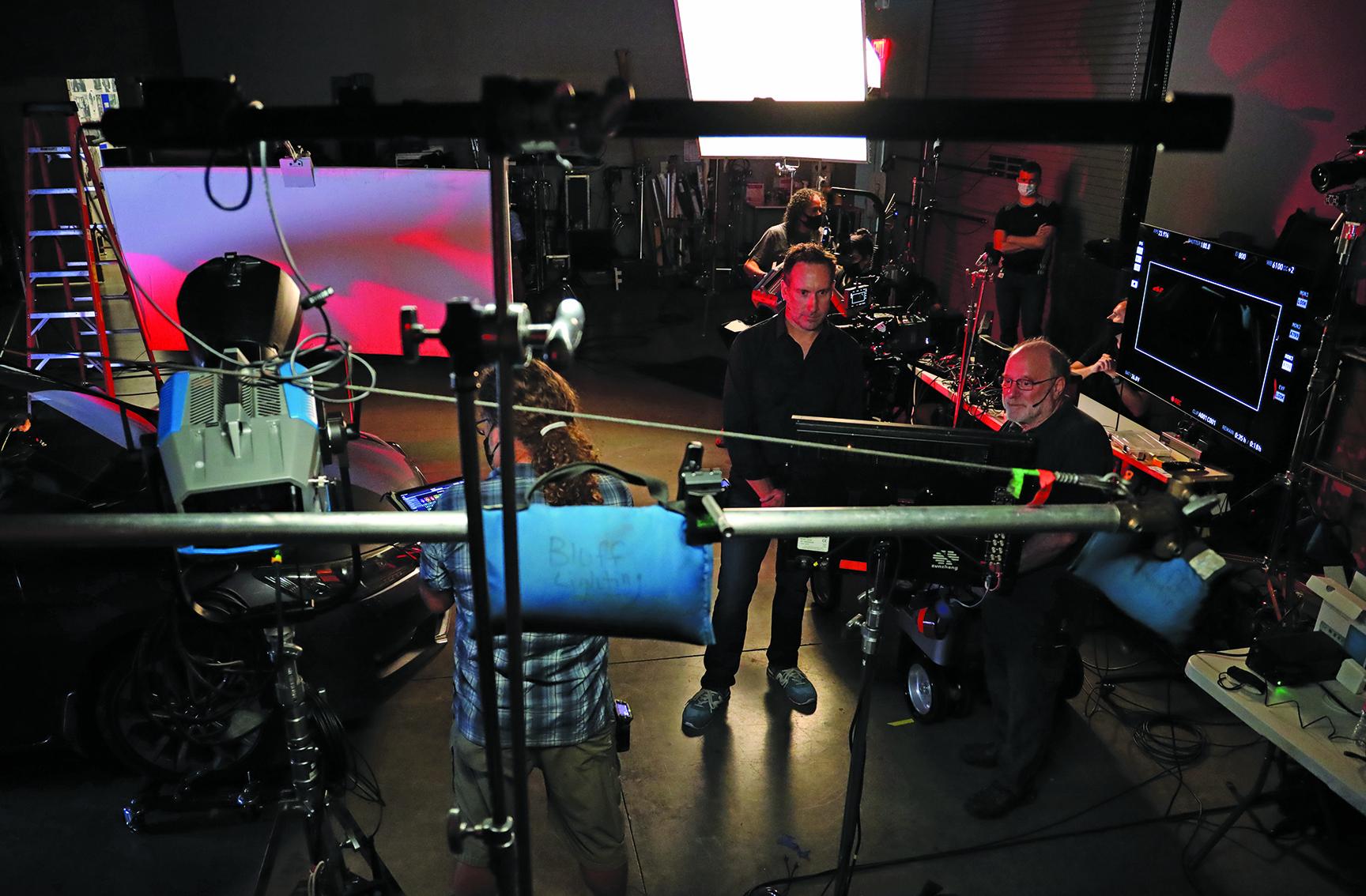

Charlie Lieberman, ASC recently completed an LED-wall shoot with Arri Creative Spacein Burbank, Calif., for an ASC Master Class on virtual production, and he was impressed with the results. “The shots we captured in front of the LED wall are completely believable as ‘live,’” he says. “We were able to adjust the contrast, color, brightness and black levels of the screen content, in-camera, to match what was going on in the car, using calibrated monitors. That’s always been the problem with lighting for bluescreen and greenscreen — you never see the results until much later.”

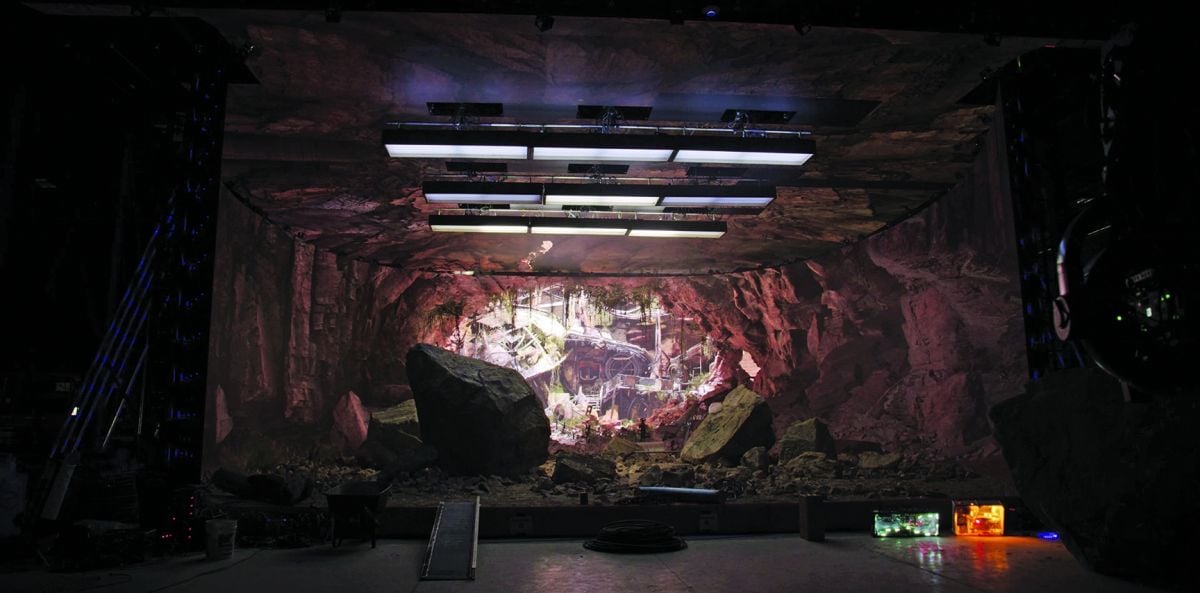

Compared to standalone-style LED-wall systems, full LED enclosure environments typically have large, curved screens with ceiling panels and full side panels. They are designed to create immersive environments.

Because the screens encompass the entire set, LED-enclosed volumes generate a large amount of interactive, emissive lighting solely from the screen content. Cinematographers can select the quality of the overhead sky fill, adjust its color and saturation, and then adjust any other virtual lighting sources, such as VFX-generated practical fixtures within the virtual sets. A significant degree of additional customization is possible on set — and it’s important for the filmmakers to determine beforehand which elements of the on-screen content will have this level of malleability — which is coordinated through the virtual-production supervisor and the brain-bar team. (The virtual-production supervisor serves as the liaison between the cinematographer, gaffer and virtual content to provide virtual lighting tools that augment the interactive content. The brain-bar crew handles all the onscreen content — taking the tracking data and integrating it to Unreal Engine and exporting the imagery back to the screen.)

An LED volume comprises hundreds or thousands of LED panels that can each be addressed individually. Therefore, portions of LED surfaces that are out of view of the camera, such as the ceiling, side walls, or any portion that’s not actively being captured — i.e., anything outside the frustum area — can run at higher or lower brightness levels, or be manipulated in any number of ways, to create specific reflection effects on, for example, a vehicle or costume.

VFX simulations of movie lights can also be created on the screens of the LED volume as off-camera effects. For instance, a large, solid shape can be conjured on the ceiling panels to create ambient lighting over the foreground subjects, mimicking Arri SkyPanels, space lights, or large solid silks. The solid can be any shape, color and intensity that’s desired.

Virtual negative fill can be designed and incorporated into LED screens as well. For the off-camera periphery of a scene, a virtual translucent frame can be placed over a section of the 3D environment to model the lighting as the cinematographer wishes, simulating the nets and silks that would be used on real locations.

Virtual light effects are fed to the LED screens via such software as Unreal Engine, MadMapper, Disguise, ILM’s StageCraft/Helios, DaVinci Resolve, Zero Density, Mo-Sys VP Pro or Notch — which factor in the entire volume’s geometry.

“The process of adjusting the lighting tools on the LED wall to create virtual fill and negative fill is remarkably fast and incredibly versatile,” says Matthew Jensen, ASC, who shot in LED volumes for three episodes of The Mandalorian’s second season, and for a recent Unreal Engine production test for Epic Games. “While shooting close-ups, I often [virtually] neg entire walls of the content while adding a bit of sparkle to an actor’s eyes with virtual fill. We can change the shapes of these virtual flags and sources, or [their] colors, to match a particular light in the content with ease. I’m usually accompanied by someone from the brain bar who’s holding an iPad with all the virtual tools at their fingertips.”

As the screens’ emissive lighting is relatively soft, actual movie lights, such as Fresnels, can be brought in to simulate the hard light of the sun or other hard sources. These lighting instruments are placed off-camera, either on the floor or suspended from the ceiling. In the latter case, depending on the configuration, individual screen modules may be removed from the volume to accommodate overhead movie lighting — though it can take a fair amount of grip work to reach the panels and take them out, depending on the screen’s access configuration. A growing number of XR stages are incorporating efficient panel-access into their designs.

Care must also be taken to keep practical or movie lighting from falling directly onto the LED screens, even when using panels with matte finishes. When extraneous light hits the screen, it can wash out the image or reflect the source on the screen itself. Thoughtful positioning of instruments and flags is critical.

“Light contamination is a big challenge, because it doesn’t take much to start milking out the blacks on the screens,” says Craig Kief, ASC, who worked with Lieberman on the ASC Master Class, and recently shot Muppets Haunted Mansion for Disney Plus in an LED volume. “With soft sources, you have to use egg crates and big solids, and with hard sources you need to use barn doors and siders,” he adds. “Depending on the reflectivity of the screens you’re using, something [as minor as] a candle or a bounce card — or even other parts of the volume — can reflect. I equate our challenges to the growing pains during the early days of digital capture or LED lighting equipment. This technology is already great, but it’s still very emerging, and its potential is incredible.”

An upcoming two-day online session of the ASC Master Class will address virtual production techniques. Full details here.