Lockdown Horror: Thrall

Though not glamorous, the challenges and creative opportunities presented by remote production are capable of bringing about exciting work.

Filmmaking during the Covid-19 pandemic has been a lesson in creatively finding new solutions, from the largest blockbusters down to micro-budget shorts. As the fall semester began at the USC School of Cinematic Arts, the school informed students that all classes, and therefore all student productions, would be completed online.

For me, a graduate student gearing up to shoot a 12-minute narrative short, the switch to completely remote production meant figuring out how to create a polished result without ever actually touching the camera on set. Our horror-film script, Thrall, which centered on the toxic dynamic between a mother (played by Susan Deming) and daughter (Haeleigh Royall), had to be radically changed in order to take place in one location. Adding to this challenge, we cast two actors in separate “Covid bubbles,” which meant that we had to make two locations look like the same house, and find ways to trick the audience into believing both actors were in the shot at the same time, when in reality they never met face-to-face and were shot on different days.

Using composite shots and sometimes body doubles, we found ways to allow the complex dynamic between characters to develop in an organic way. This was made easier by using the same lights in both locations and matching color temperature and RGB color from one location to the other. From within my bubble, I myself made an appearance in the production as a body double — setting camera while at the same time being directed by our intrepid director, Xanthe Pajarillo. We leaned into a found-footage aesthetic, allowing us to capitalize on the fact that the actors would be recording themselves.

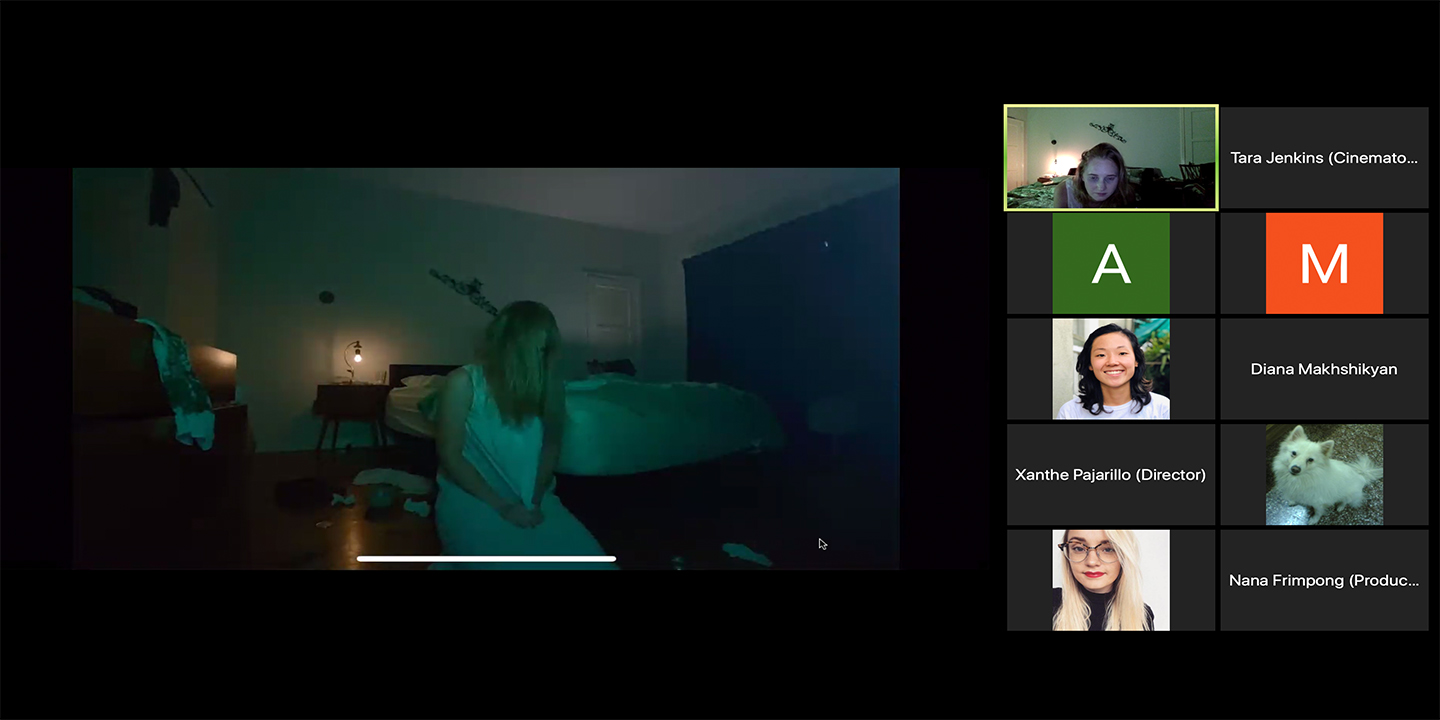

The new remote-production rules also meant new considerations that were not even on the radar pre-Covid. Suddenly, the speed of the actor’s Wi-Fi was of paramount importance, as streaming takes through Zoom was the only way the crew could see what was happening on set. Casting actors meant also casting locations, and the labor-intensive aspects of setting lighting and production design had to be tempered by the number of hands in the actor’s bubble that could help set up each scene. Any equipment shipped to an actor has to undergo a rigorous cleaning and have a 36-hour turnaround time to make it as safe as possible for the actor to use it.

This creates the possibility of spending a semester and thousands of dollars on a production with a crew and cast that never actually meet in person — and might not meet for many months to come. It also creates a restricted form of being “on set”; the majority of the day is spent sitting at a table, and “lunch” means walking two feet to your fridge and taking a break from the computer screen. Though not glamorous, the challenges and creative opportunities presented by remote production are capable of bringing about exciting work.

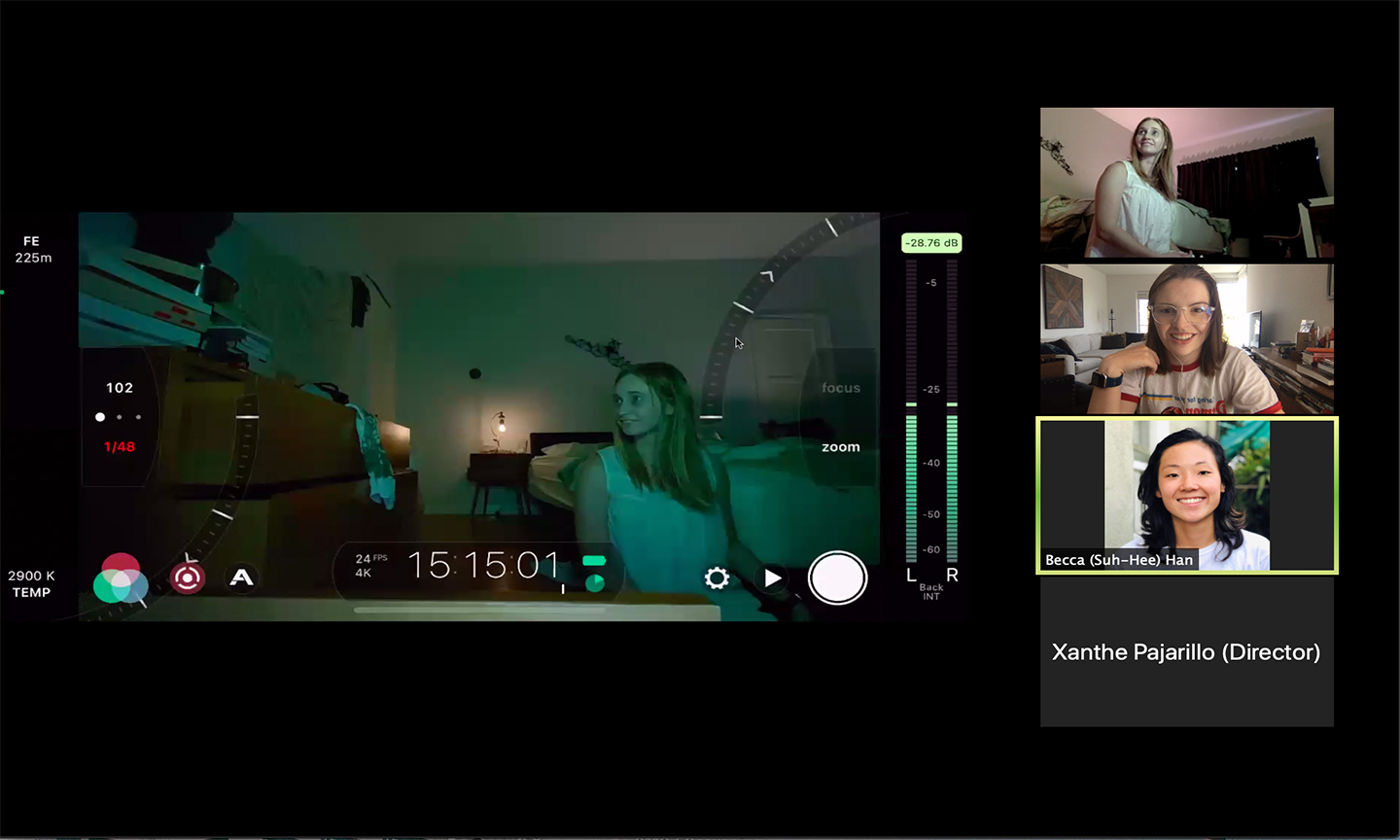

Shooting a completely remote production requires intense planning and a reliance on actors to not only give the performance the story needs, but also act as camera operator, grip and myriad other crew positions during a single day. As a cinematographer, my role encompassed lighting the production, retaining control of my vision without touching the set, and putting my crew and the actors at ease as much as possible. Some of our scenes involved difficult character work, as our lead actor devolves into madness over the course of the story, which culminates in a self-exorcism scene. Cognizant of the low-light capabilities of the iPhone 11 and GoPro Hero7 Black, we worked to create a space that was dark and moody but also had enough light to minimize noise. I came up with a lighting design that could be almost completely controlled by application once rigged in each room. Using an RGB NanLite PavoTube, two Aputure MCs, two Quasar Science tubes — one daylight balanced, the other a Crossfade — and dimmable LED bulbs, I was able to instruct the actors to use presets on the applications to achieve the look and color I’d been able to work out by testing the lights in my own bubble. As much as possible, we tried to respect the actors’ need to prepare for each scene, and streamline the technical aspects so we could put story and character first.

The iPhone, which was paired with Moment lenses for certain shots, was employed for the daughter’s ostensive video message to her girlfriend, while the GoPro served to provide security-camera footage from around the house.

To further facilitate the production process, I gave the actors a 15-page PDF file that explained how to use the lights, the GoPro Hero7 and the iPhone 11.

Forethought and clear communication were the make-or-break factors on set every day. Every aspect of the in-person shooting process that could be replicated remotely was, from location scouts via Facetime to Zoom breakout-room rehearsals with the actors. Using a dual system of Zoom to view the set and Google Duo for walkies for the crew, we were able to stay in constant communication and change things quickly and in real time.

The waiting period required for cleaning equipment, which prevented us from borrowing lighting from USC as usual, led us to buy most of our gear, apart from the cameras. This limited the amount of lighting gear we could obtain, but it also forced us to be especially creative in our shooting schedule and how we blocked each scene. This gave the actor great flexibility, as we lit the rooms to allow for improvisation and for the scene to unfold differently each time.

The budgetary and technical constraints of our project required us to approach shooting in an organic way, where the space was lit as naturally as possible. Since the whole room might be shown, and we were restricted from asking the actors to go outside to light through the windows, we needed to create lighting that either blended in with the décor of the home or hid above the plane of view — while still giving a key light to the actors in the important moments, so that we never lost their eyes. By placing the NanLite and Quasars above window spaces to supplement and add color to natural lighting, we were able to do just that, without worrying about lights potentially being in eye-level moving shots operated by the actors.

Over the course of two weekends, we were able to finish primary shooting without ever meeting each other in person, other than to drop off equipment at the door while wearing full personal protective equipment.

The exciting challenge of remote filmmaking does not come from how much or what kind of equipment can be used, but rather how to make the process work with both hands tied behind your back. The truest test of your knowledge of your craft is whether you can articulate what you need well enough that someone who knows little about your craft can execute your plan. Through the remote-production process, the concept of filmmaking is stripped down to its core, and you have to focus on the fundamentals of telling a visual story. Nothing else matters — except Wi-Fi speed!