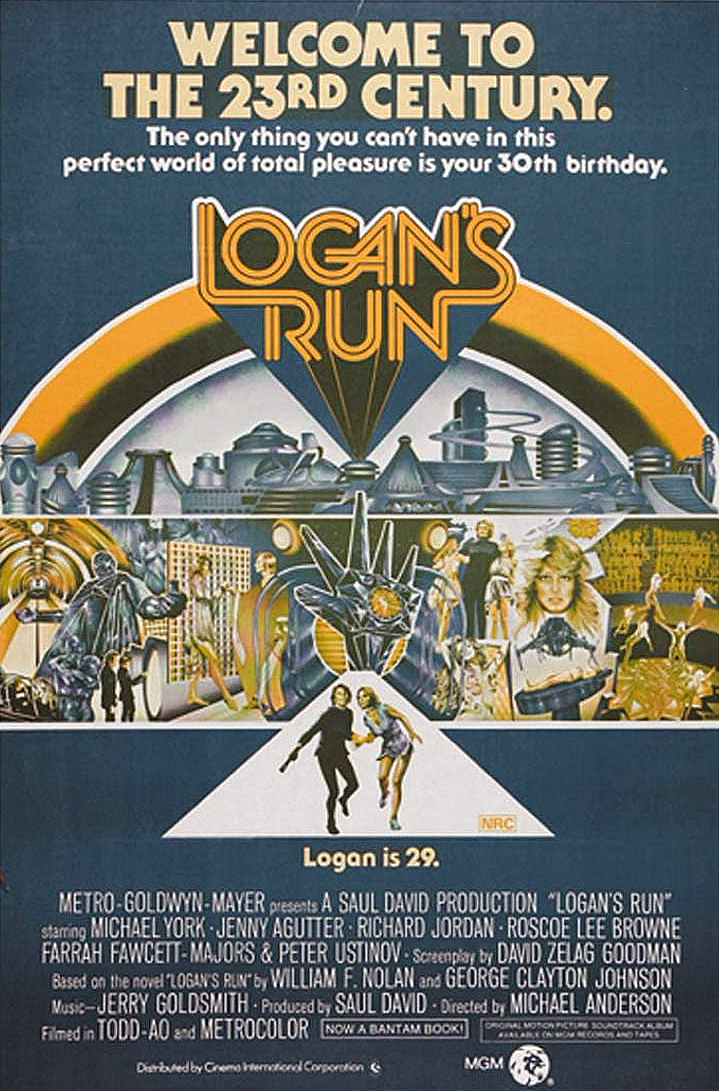

Logan’s Run: Magic for the 23rd Century

Snorkels, lasers, holograms, computer graphics, matte paintings, double printing and a few things never tried before blend to bring a society not yet born to life in credible fashion on the screen.

By L.B. 'Bill' Abbott, ASC

The special photographic effects for Logan's Run are concentrated mainly in three sequences: (1) the Carousel, (2) the exterior and interior of the futuristic Domed City, and (3) Washington, D.C., which at this date, 300 years in the future, has deteriorated to a vine-covered rubble similar in its overgrown state to Angkor Wat.

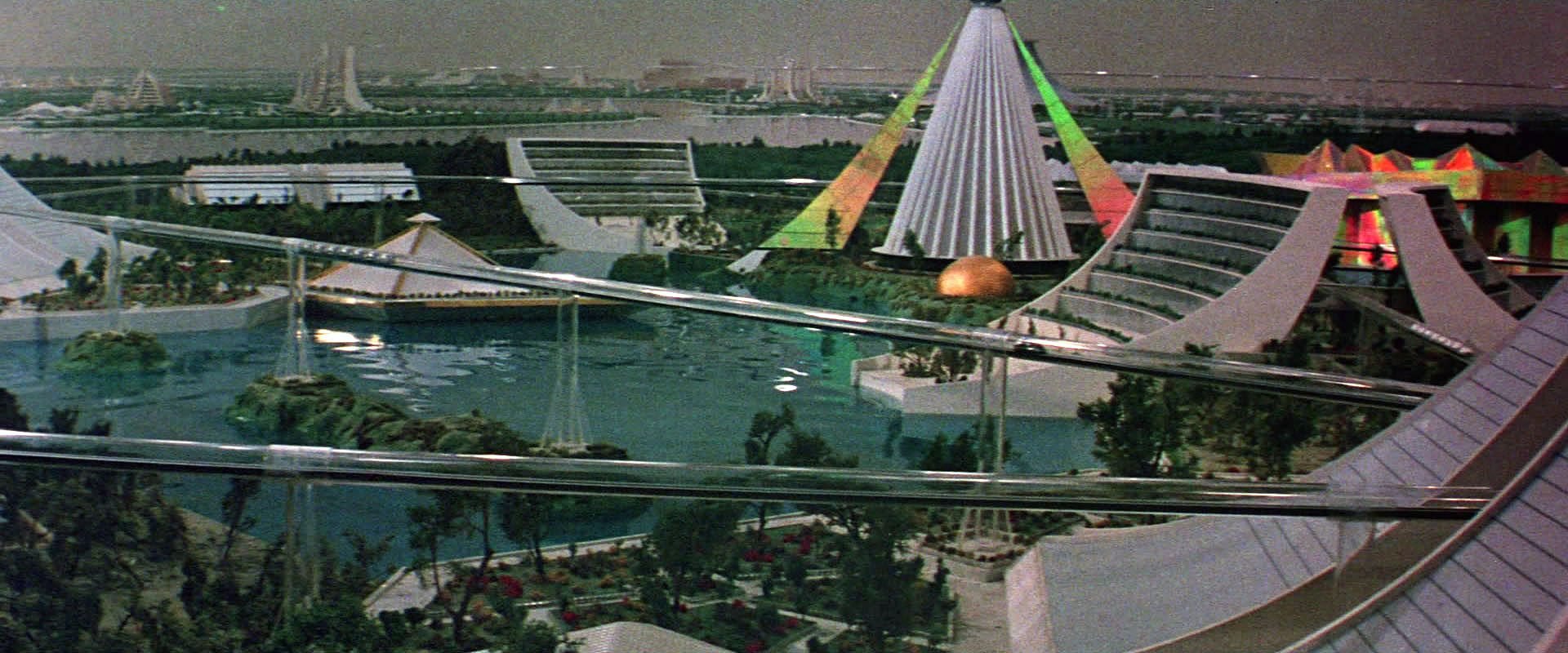

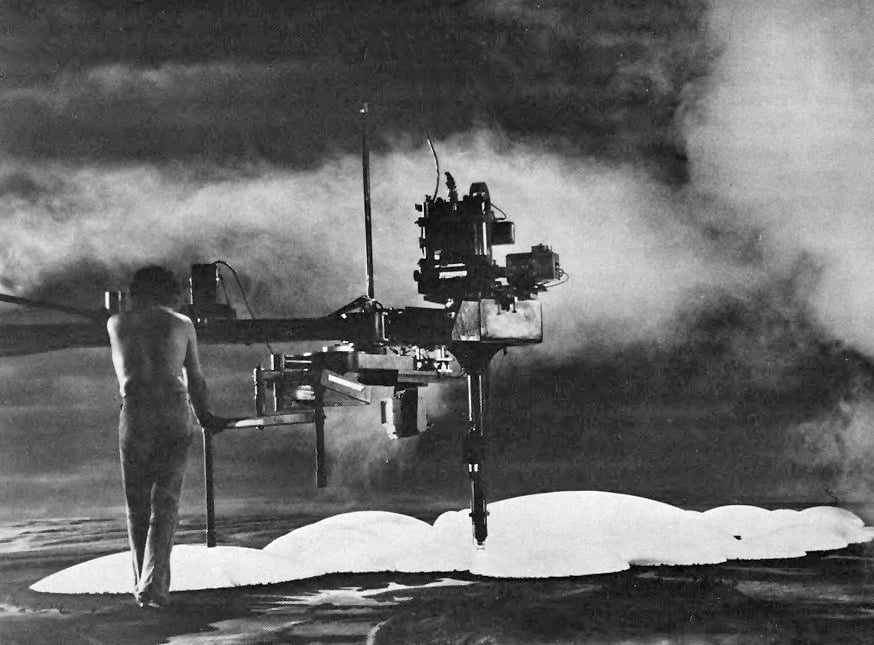

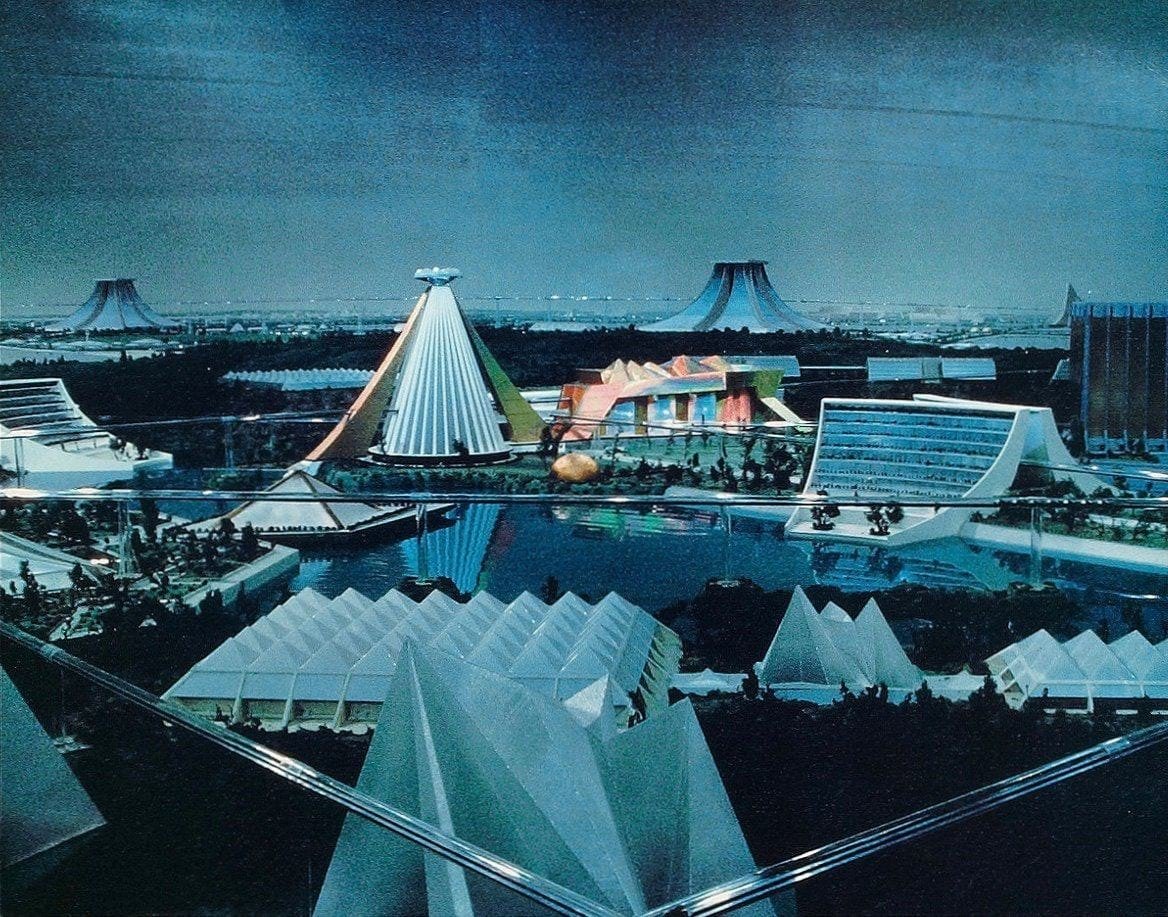

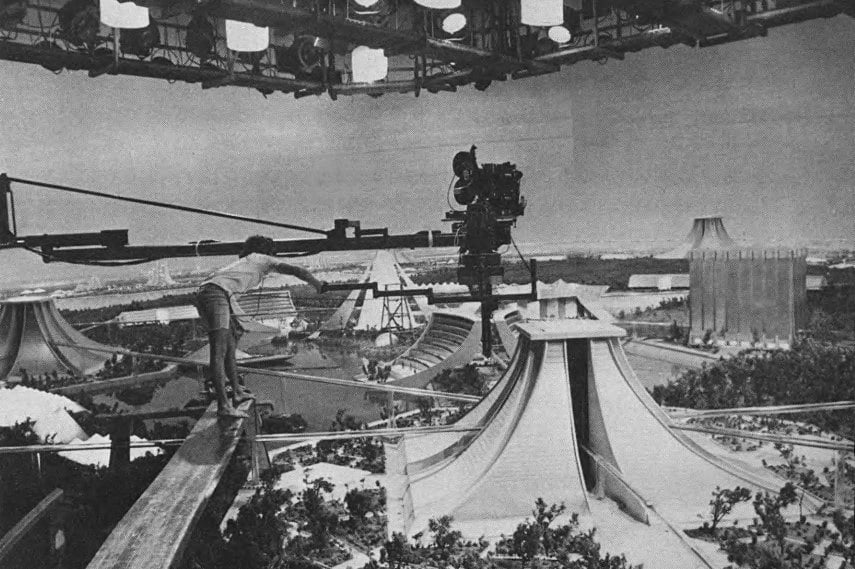

Most of the shooting on the miniature city was done with the Kenworthy Snorkel System, which gave us great fluidity of camera movement and made it possible to get a low horizon on a small miniature.

In the opening of the picture we see a long shot of the domed city at night, with light glowing through the domes. We push in toward one of the larger domes and do a sort of white-out dissolve, as if going through the dome into the interior of the city. The camera then carries on across to show the whole miniature set of the city. In the city are little maze-cars moving through transparent glass tubes. We moved them at a rate that seemed correct for cranking at 24 frames per second. After scanning the entire city, the Snorkel camera picks up on a single maze car and follows it into a building. At this point, a cut is made to the full-size set, where a fellow jumps out of the maze car. He’s a “runner” trying to escape from the domed city, but he’s caught and shot. It makes a very interesting opening for the picture.

I had never worked with the Snorkel before, but I found it to be a very good piece of equipment. When you put the anamorphic lens on it, the working aperture is f/11 at 24 frames, so you have to use an unusually high light-level in order to balance to that kind of key. There was no problem when we were outside the dome, because the only movement involved was that of the camera and the clouds in the sky above the city.

A grip rides the arm of the Snorkel in order to manipulate it and he has a monitor through which he can view the scene. The grip we had was very good at it, so the whole sequence was shot quite easily.

The exterior and interior of the domed city were small-scale miniatures. The exterior was about 1/400 full size and the interior was about 1/48 full size.

There were four spots in the sequence of the miniature city where we matted in people. We made specific shots of the miniature design so that we could put people onto the walkways. Then we went up to the Sepulveda Dam, where they have a large concrete area and we shot the people on the concrete, later matting them into the miniature shots. Having the miniature to line up on, we could place the people where we wanted them. We did this using a rather new technique. We shot them normally, of course, and then made a combination, using the CRI [color reversal internegative] method. In other words, their surround was white, which made it possible to burn the people into the CRI of the miniature, after having lined them up properly. It was kind of like a traveling matte, where you have an oblique angle and they are backed up by bushes and trees, with some bushes in front. You make a matte for the bushes that are in front and then you use a hold-out while you are printing the miniature set, later filling it back in with the negative.

These were pretty long shots and they seemed to work alright. The challenge in shooting a miniature is to keep it from looking like a miniature. To solve this problem, in several instances, we shot people against a bluescreen and then put them in front of the miniature city. There were maze cars moving in the miniature and, in a later sequence, explosions going off and lights flashing, so you had the feel of them being in a live city.

We had a wonderful backing to simulate the dome and we had two modes of lighting: one for night and another for day. We changed modes simply by turning the lights on in the buildings and cutting the overall light down — and vice versa for day.

For filming the sequence that takes place after Logan shoots the computer and the city begins to explode, we had to get off the Snorkel and settle for higher lens angles, switching to conventional high-speed anamorphic lenses to permit cranking at five times normal speed. The accelerated frame rate was necessary because the miniature had been designed to such a small scale.

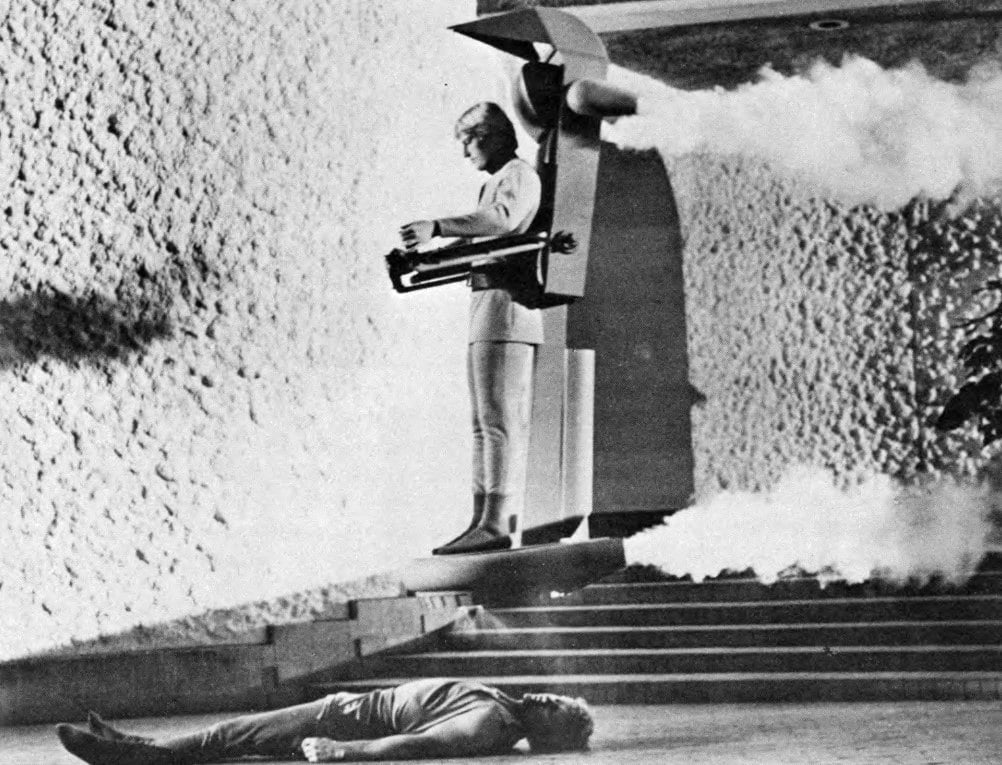

One of the techniques we used to get an effect in Logan's Run was rather unique. Early in the picture a runner is killed by a Sandman, who then calls on his walkie-talkie to ask for a “cleanup” in the area. A couple of fellows called “Stickmen” come riding in on strange jet-propelled vehicles that squirt smoke out the back and they are supposed to spray the dead figure with a substance that dissolves it down to a residue of crystals, which they then vacuum up.

We tried using laser beams to achieve the effect, but it wasn’t satisfactory. Then somebody in the Mill Department at MGM advised producer Saul David that if you make a figure out of Styrofoam and then spray it with certain chemicals (I think we used a combination of methane and ketone) the Styrofoam figure will just melt away. We ended up by using that technique to make a transition from the real “corpse” to the Styrofoam duplicate, which just melts away, leaving a residue of crystals.

motion in any desired direction. This is one of several types of fanciful vehicles created by

Special Mechanical Effects expert Glen Robinson and his staff for the film.

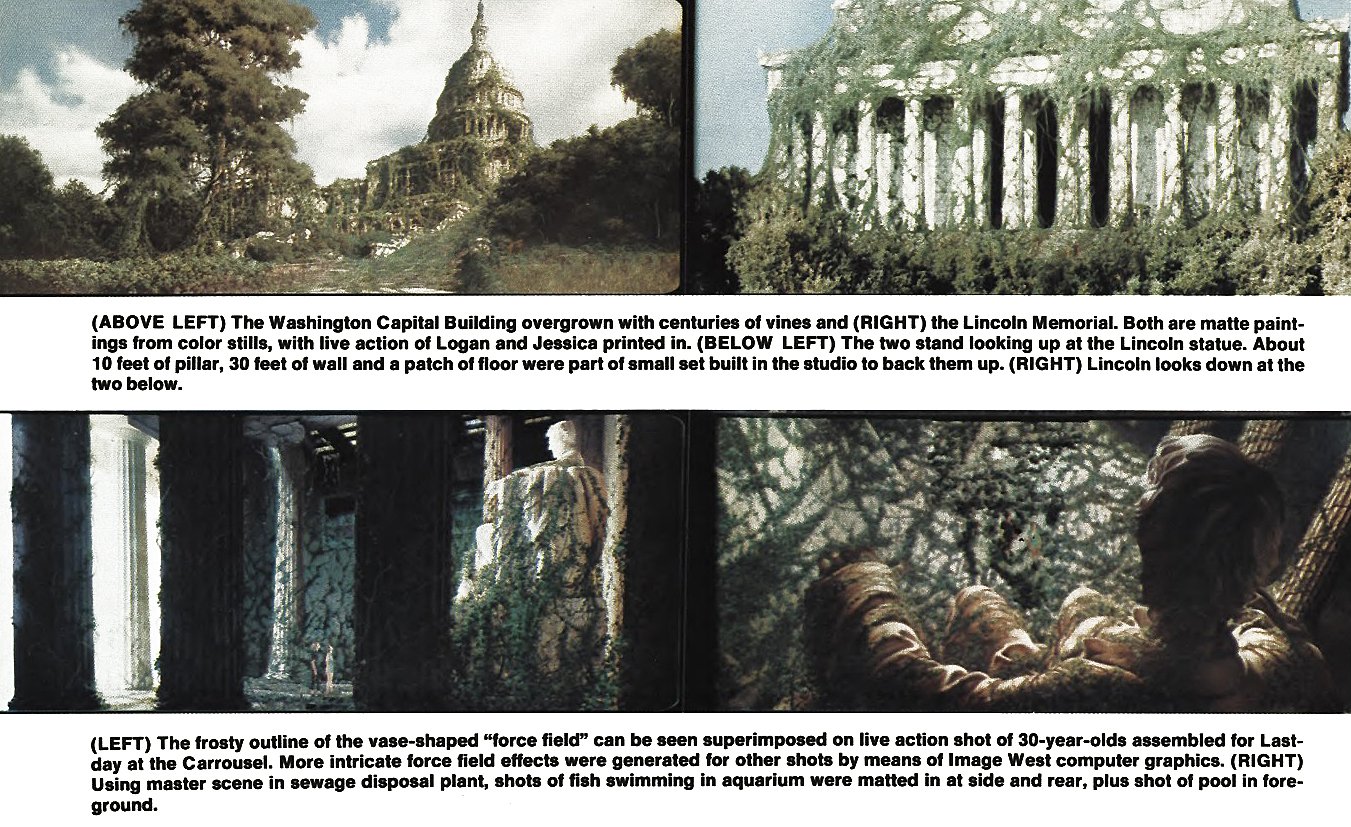

The scenes shot in what is supposedly a vine-covered, deteriorated Washington, D.C. of the far future were created through the use of a conventional matte process. Prior to the start of production, illustrators drew up sketches of the needed scenes and, using these as a guide, one of the artists went to Washington and had matching 4"x5" color stills shot. These were enlarged and mounted onto masonite boards to provide the matte artist with a base onto which he could add the necessary deterioration — rubble, vines, etc. They also served as a means of making line-up films to enable us to photograph the people to the correct size and position within the composition of the scene.

For example, for the scene in which we see a side view inside the Lincoln Memorial, with Logan and Jessica looking up at the statue of Lincoln, we had on the set in the studio a piece of column about 10' tall, a patch of floor (laced with vines) and about 30' of ivy-covered wall. The rest of what appears on the screen came from the still photograph shot in Washington.

In the long shot of the entire exterior of the Memorial, where they are seen going up the steps, we built a section of steps big enough to back them up, photographed that piece, and then inserted it into the overall photograph-painting of the structure.

The matte process was used in several other sequences of the picture. For example, when Logan and Jessica are fleeing from the domed city they pass through what is supposed to be an undersea complex, with large glass ports through which they can see fish swimming in the ocean outside. The basic scenes were shot in a former sewage disposal plant that is no longer in use. The final scene in the script called for a glass port filling one entire side wall and another port taking up the end wall, as well as a pool of dark water in the foreground.

We bought some conventional, inexpensive aquariums from a store and rented some fish to put inside them — fresh water fish like gars and others that could be made to look like deep-sea fish. I put the aquariums up on five-foot parallels in order to get the correct lens-height. I made a line-up shooting down the side of one tank, with the other tank at the end, and cranked the scene at four times normal speed, figuring that, in terms of a 1/16th scale, this would make the fish move as if they were 16 times larger than their actual size. We also made a painting to take out what we didn’t want and paint back in what we did want. For the dark pool in the foreground, I made a shot of a swimming pool and matted that into the proper area.

We used mattes also to extend the scope of the fantastic Water Gardens filmed in Fort Worth, Texas. We added on to the structure itself and also filled the background with open ocean.

I’d like to say a word about the advances in matte painting that were applied in Logan's Run. For years we have used as much photography as possible in creating matte paintings. For example, if you had a shot of a Western town and you wanted to put the snowcapped Canadian Rockies behind the town, you would get a black and white photograph of the mountains and blow it up to a large size (so that the matte painting artist wouldn’t have to paint the Lord’s Prayer on the head of a pin, and could work in a scale compatible with the size brushes he wanted to use).

Having this photographic base to start with, he would qualify it by, perhaps, putting the snow on the mountains. Then, if the scene was in color, he would glaze the photograph in the proper colors. Today, the matte artist starts with a color enlargement of these same mountains and he doesn’t have to color it in. He simply augments it by adding the snow, for example, just as our artist added the overgrowth of vines to shots of the buildings made in Washington.

Skilled matte painting artists are very rare. There’s only a few of them around anymore, but when you start them off with reality, so to speak, and they simply have to qualify or embellish it, you’ve got a winner right off the bat.

Using color prints as a basis for matte paintings would seem so obvious that one might wonder why it has been done only recently. All I know is that when, in the past, I tried to get large enough color blow-ups nobody was manufacturing printing paper to that scale. But apparently a demand for such paper developed in the advertising field, so that paper manufacturers started producing it in rolls 100' long and 50" wide.

The color blow-ups we got for this picture were made on a paper that has essentially a semi-matte surface. You can paint on it with almost anything you wish except watercolor — water disturbs it. Alcohol or varnish doesn’t affect it. So the artist can paint onto it and, if he changes his mind, wipe the paint off and start over again. Using such blow-ups as a basis for matte paintings offers such advantages in terms of speed and realism that I think they will continue to be used more and more.

There were various effects in the script that called for the use of lasers. For example, each of the people in this future society has in his apartment an electronic transport machine capable of what might be called “teletransference”. He simply punches up the characteristics of a certain person on a remote control box and an alcove becomes illuminated with a strange ectoplasmic effect which eventually forms into the shape of a person and, finally, the live person. The “strange ectoplasmic effect” was achieved by means of lasers, augmented with wiggle glasses.

In a rather amusing sequence, Logan apparently punches the wrong button on the remote control box of the electronic transport system and a boy materializes. Not being very happy with this turn of events, he dials the boy out and tries again. This time, a pretty young girl, Jessica, appears in a similar manner and Logan ushers her into the room.

In the sequence where Logan destroys the computer, we use laser effects behind the lettering on the screen, which goes crazy when the computer breaks down. Then, when all the circuitry in the city goes out of control and there are all kinds of electrical explosions, we use the lasers to double in light show effects over the city in a staccato manner that gives an appearance of something happening atmospherically.

At first MGM talked about getting an outside company of laser specialists to produce these effects, but it soon became obvious that in order to have the degree of control needed to inject whatever effects were desired into the picture, it would be better to create them in the studio. So the studio bought one blue and one green laser and rented a red laser to complete the spectrum. We set them up on the stage and what actually happened was that we would project the laser beams onto a translucent screen and modulate them with many kinds of plastic that were serrated and dented and could be rotated. We put them on motorized wheels that would revolve them very slowly to produce a galaxy of light effects. Of course, once you got these onto film you could do anything you wanted with them. For example, if you wanted them to come through like a lightning effect, you could create this optically by means of a variance in exposure.

From the standpoint of photographic special effects, perhaps the greatest challenge in Logan's Run was the Carousel sequence, which depicts a religious-type ceremony that takes place in a large circular arena. The premise is that when you have reached the age of 30, you must go.

Those who have reached their “Lastday” assemble in the revolving arena and are supposedly levitated by a force field emanating from a crystal high above the floor. As the levitated people reach the upper area, they flame out; i.e., explode.

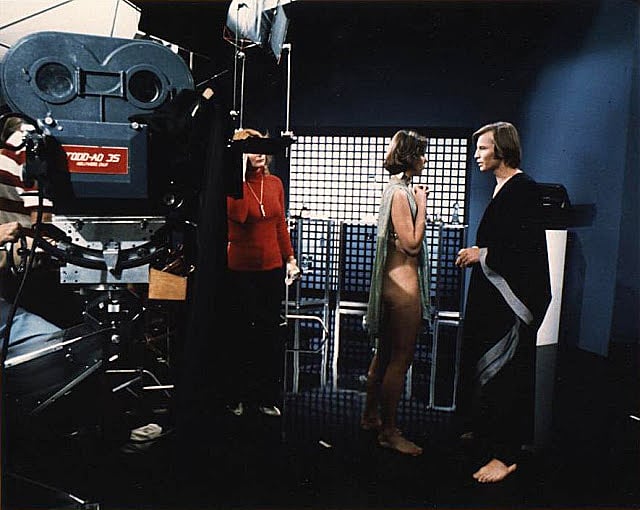

Glen Robinson devised a fabulous rig that had a revolving base which was synchronized with an overhead revolving apparatus. It was equipped with electric motors and wires, making it possible to “fly” 15 to 18 people at once. The rig allowed for a variety of camera angles of the people flying in front of the audience, revolving and tumbling as they flew. To get an “up” angle, we actually turned the set upside-down, in effect, shooting downward at what was supposed to be the ceiling crystal and letting the fliers descend to it.

those who have reached the age of 30 and are slated to die in spectacular flame-outs, vainly trying to reach the crystal and renew their lives. In the actual sequence as filmed, the Lastday participants are dressed in grotesque costumes, complete with death masks (below).

According to the script, those that levitate all the way to the top are given the opportunity of being renewed — a sort of reincarnation, so that they can live their lives all over again. At the end of the film, however, it comes out that this is a big lie. Nobody ever gets renewed. They all get flamed out.

In approaching the effects for this sequence, my first problem was creating the force field in a visually credible way. I started out by building some cone-shaped forms and filling them with various kinds of cellophane and lighting them with colored lights as they revolved. This idea really stemmed from a television series I’d worked on called The Time Tunnel, in which characters were teleported to the past or future and we would always show them going through this “goop,” as I called it.

The effect, as it turned out, had some merit, but it just wasn’t really right. Saul David suggested that perhaps we could get what we wanted by means of computer photography, so we talked with a company called Image West which creates computer images, mainly for commercials. In our beginning experiments with them the effects were shot on tape and then transferred to film, but we found that quite a lot of quality is lost by this method. Then I found out that the effects can be filmed right off the tube with better quality. It needed only to be a black and white image, to which you could add any colors desired. We double-printed these effects over the Carousel scenes to create a visible force field.

In the beginning of the sequence, the people assemble at the arena and look up toward what is supposedly a very distant crystal, similar to the red one they are standing next to, but white in color. (We shot this on the same stage as the arena, but used a smaller crystal to make it appear to be farther away.) As the crystal glows on it “comes alive” and begins to sparkle. The sparkle was accentuated by using a star filter. However, in order to make a star filter work you need a pretty strong light source — so we got some of those little quartz light units that are pinned to life jackets as a safety device. They flash on every half-second and are extremely brilliant. These little lights were mounted on the crystal in order to “animate” the sparkle.

As the crystal starts to sparkle, the force field (which we generated on the computer) comes down toward them in the form of a cylinder with a serrated edge and it covers them like an umbrella. As the base which they are standing on starts to revolve, the cylinder fades away, but is replaced by a vase-like form filled with a smoke pattern that is revolving. We elected that this should only be sensed, because it would have been wrong to make it a solid kind of thing. It required a delicate balance, but the result is quite believable when you see the smoke pattern rising within the vase as a levitating force.

In addition to long shots showing all of the fliers in front of the audience, we made shots of individual fliers from various angles against a black background, so that we could matte them in. These fliers were dressed in fireproof clothing and had explosive charges hidden on them which they could trigger on cue by means of a hand button. When the explosions occurred they completely obliterated the figure, causing it to appear to flame out. Then, by cutting away at the peak of the explosion, the illusion of the figure vanishing was achieved.

We shot these cuts of the individual fliers flaming out and then optically inserted them into a longer shot showing other fliers. For example, you’d take a shot showing perhaps eight people flying and then, having flown your exploding person at the same rate of speed, you’d pick an area where he could be inserted between two of the other fliers and just blow him up, after which you’d stop the double exposure. It’s very believable. As a matter of fact, I think that visually the shots of these people dressed in their bizarre costumes is probably one of the highlights of the picture. I’ve never seen anything like it before, where you are flying 16 people at once who are rising and lowering and tumbling in the air. It’s really fantastic!

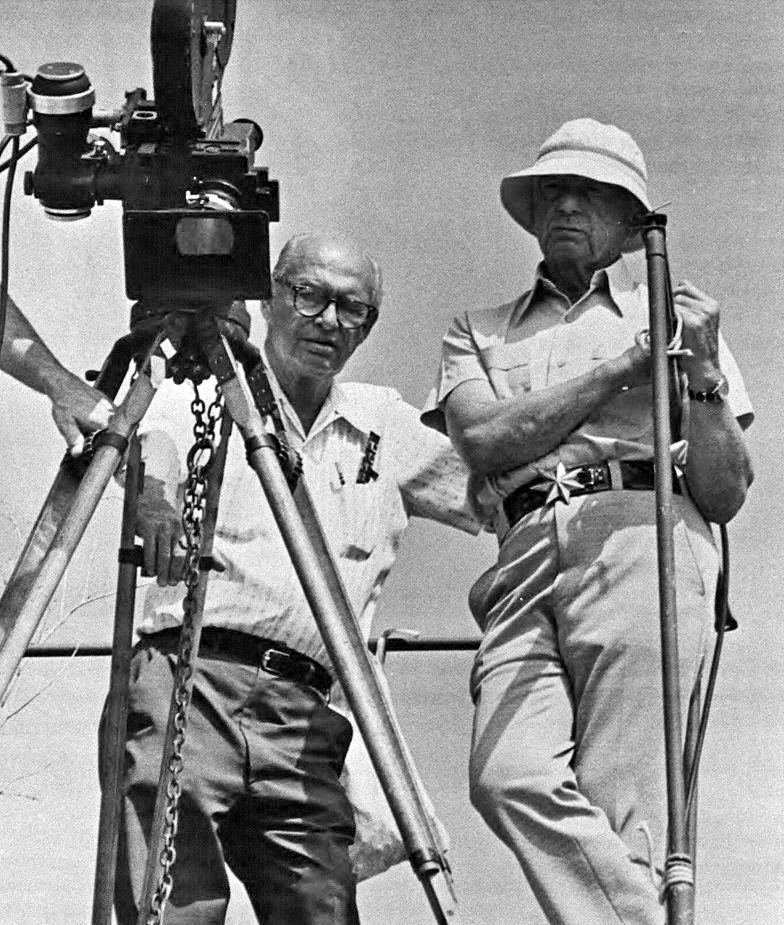

For more on the production, here’s our interview with director of photography Ernest Laszlo, ASC, as well as our cover story from June of ’76: Logan’s Run and How It Was Filmed.