Long Road Home: How It Ends

Peter Flinckenberg, FSC and director David M. Rosenthal welcome AC to the Canadian set of Netflix’s apocalypse road movie.

Peter Flinckenberg, FSC and director David M. Rosenthal welcome AC to the Canadian set of Netflix’s apocalypse road movie.

We pull up to set on day 31 of a 38-day shoot in the Canadian rural municipality of Brokenhead, northeast of Winnipeg, Manitoba. Crew vehicles line the dirt road. The buzzing of a generator, and not much more, separates us from the silence of the surrounding forest. It’s nearly sunset. Los Angeles-based Finnish cinematographer Peter Flinckenberg, FSC emerges from a path and invites us to watch the capture of a main character’s pivotal decision for the Netflix road-trip thriller How It Ends.

The scene’s ambiance is deceptively serene, an unsettling quiet in the aftermath of a harrowing adventure. A mysterious apocalyptic event has wiped out much of the U.S. and prompted Will Younger to drive cross-country from Chicago with his future father-in-law, Tom Sutherland — a former military officer — to rescue Will’s pregnant fiancée, Samantha, in Seattle. Tom’s story arc has recently ended and the tale is nearing its conclusion.

A couple of crewmembers wield handheld smoke machines while two others wave tall snow candles, creating a melancholy haze accented with falling ash. There are no lighting fixtures in sight. Actors Theo James and Mark O’Brien — playing Will and the suspiciously antagonistic Jeremiah, respectively — emerge from the woods and turn onto the main path, walking toward us.

Roger Finlay operates A camera — a Red Weapon Helium 8K, fitted with a Vantage Film 80-180mm (T2.8) Hawk V-Plus Anamorphic Zoom, on an OConnor head mounted to a stationary Chapman/Leonard Hybrid IV dolly — on a track to the right of the path. Len Peterson operates B camera — a Freefly Systems Movi rig fitted with another Weapon Helium, this one with a spherical Whitepoint Optics TS70 tilt-shift lens — tracking backwards on foot. The cameras record to RedMag 1.8" SSDs.

Flinckenberg and director David M. Rosenthal keep an eye on two tripod-mounted SmallHD monitors, one displaying the tighter, more intimate Movi-assisted shot, and the other a wide through a stretch of ominous atmosphere. Christopher Raucamp and Christopher Howell, respective A- and B-camera 1st ACs, peer into their monitors that are hidden beneath black cloth.

“Tremor!” Rosenthal calls out. Peterson stops as the actors react to a quake.

The Movi’s monitor reveals the light touch that Flinckenberg has chosen for the Whitepoint’s effect — a subtle blur around the frame’s sharp center that isolates James and O’Brien and lends a haunting look to the wooded surroundings. As one of the lens developers for Whitepoint, the cinematographer is well versed in the subtleties of this particular glass.

“There was a danger but also a beauty to the floating ash,” Flinckenberg says later. “It’s one of the key scenes in the movie, and we [shot it] almost completely in available light. I used the Whitepoint optic with a very slight swing, so the background — the forest — becomes a bit magical and maybe a little weird.”

“Shooting through layers,” Rosenthal offers, “through smoke, through glass, in the woods through the trees — obscuring what we see — has been a goal, visually, in this movie from the beginning. It was actually one of the things that drew me to Peter; he loves to do that as well. We share so much of the same aesthetic in a lot of ways.”

James aims a blank-loaded pistol at B camera, with Rosenthal standing just behind Peterson. Flinckenberg — known for the 2014 ASC Spotlight Award-winning Concrete Night (AC Sept. ’15), Season 1 of Showtime’s I’m Dying Up Here (AC Sept. ’17), and the feature Come Sunday — keeps watch at the monitors as James fires a single round.

Much of the production, Peterson notes, has been shot with a “more frenetic handheld, so it felt really nice to use the Movi and have this more peaceful feel to it. You know that all hell’s gonna break loose and you’re just waiting for it to happen, but it suddenly calms down and sort of floats through the forest with these characters, which I thought worked really well. It’s like the eye of the storm.”

Peterson adds that the lens on his rig for this sequence alternated between a 40mm and 80mm Whitepoint. “The 80mm is quite challenging,” he says, “because it’s a pretty long lens, and you’re backing up through the woods over all kinds of terrain. I’ve never employed swing-shifts in the way that we’re using them here. It’s always been quite rare, and here Peter’s really gone after that for the finale of the film.”

The 2x anamorphic Hawks and spherical Whitepoints were the primary lenses on the production. Kowa Prominar anamorphics were employed when lighter weight was a priority, and a Nikon/Hawk 800mm anamorphic telephoto and an Arri/Zeiss 100mm spherical macro were used periodically as well. In addition to the 80-180mm, a 45-90mm (T2.8) V-Plus Anamorphic Zoom was on hand, and “we also had a 250mm T3 Hawk V-series anamorphic prime with an extender,” Flinckenberg says.

It’s approaching dusk. Rosenthal and Flinckenberg are concerned about losing light. ISO has been upped to 1,600, having already climbed from 800 to 1,280. The cinematographer wonders aloud, “Is it too dark?” He checks his meter. The crew is tasked with grabbing one last take of Will swiping Jeremiah’s gun and running.

After a nighttime lunch, we return to set to find what can only be described as an enchanted forest. Smoke swirls among the trees and the crew is hard at work in silhouette against an ethereal green light that pours downward through the leaves.

Two condors have been fitted with 18K Arrimaxes gelled with Cyan 60. Gaffer Jani Lehtinen — who also hails from Finland — clues us in on the upcoming “lighting gag where the crew will move the 18Ks a little [with ropes], which will move the shadows slowly, but not too much. It will be a strange look.”

Flinckenberg elaborates, “There are strange phenomena throughout this film, such as heat and strange colors in the sky. The idea behind the turquoise/peacock color in this scene is that there is a very intense Aurora Borealis — the Northern Lights.” Regarding the in-camera effects for this sequence, as well as those throughout the production, the cinematographer notes, “I think it’s very important, especially in this kind of film, that the actors understand what kind of situation they are in.”

James concurs, noting that “sometimes [on other productions] the lighting on set is very different from what it will look like [onscreen], and you’re asked to imagine it — in the grade it will be darker, dirtier, moodier — but [Peter] was able to make it feel like that straightaway, so when you were in the atmosphere of the scene, [it] was pretty much already there.”

Flinckenberg makes special mention of respective hair and makeup department heads Stacey Mendoza and Jo-Ann MacNeil, whose contributions have been essential in achieving the production’s in-camera objectives.

“The other sort of philosophy that we’re adhering to on this movie is that although there are visual effects and there’s spectacle, we don’t want to ‘fetishize’ the effects,” says producer Paul Schiff, who has been on-site throughout the shoot. “We don’t want the visual effects to be the story. The intensity of the emotional dynamic between the actors who are running this gauntlet is the most powerful thing of all, and the visual effects [should support] that and never overwhelm or distract from it.”

Also on-site is producer Tai Duncan, who adds, “It’s just such a wide mix of work that we’re doing on the movie — from urban to rural shooting, both visual and practical effects, some really significant stunt work, traditional composed work, and some really beautiful rural countrysides.”

“All I need is a miracle,” the grip crew sings as they set up dolly track in the luminescent forest. A campfire — in fact fueled by a propane rig and adjusted for height and intensity — burns a few yards from us. Facing the fire, fitted with DOPChoice Snapgrids, and mounted on handheld booms are two battery-operated, DMX-controlled 4'x2' LED Carpetlight CL42s to bring up the blue and fire-matched orange on the actors’ faces. In the distance are an Arri SkyPanel S60-C and an S30-C, as well as an L7-C Fresnel, which represent a cabin deeper in the woods. The relatively simple wireless setup here, as we’ll later discover, is just the tip of the iceberg for this production.

After hearing it described by multiple crewmembers, Flinckenberg invites us onto the “Magic Bus” — command central for How It Ends, and where the cinematographer prefers to observe what the cameras are capturing. “I like the bus,” he enthuses.

We enter the U-Drive Bus Rentals GMC C5500 shuttle to find it rigged with two primary monitors — a Sony PVMA250 and a Flanders Scientific CM250 — as well as an MA Lighting Dot2 XL-F dimmer board with a Dot2 4-port node for extra DMX outputs, a DIT cart running Pomfort LiveGrade, and remote Libra-head wheels, in addition to video and audio stations in the back. On a typical shoot day, the vehicle holds the director, cinematographer, board operator, gaffer, key grip, camera operators, camera assistants, digital-imaging technician, producers, script supervisor, and video-assist and audio operators. Once again, this extensive mobile headquarters will make a lot more sense tomorrow when car work resumes.

Producer and unit production manager Patrick Newall explains that after some discussion and testing, the production chartered a “Teradek system and grips, and we rigged out a bus and put in two and sometimes three monitors, and some smaller monitors. David has a handheld. We have full sound-mixing capability on the bus. [We have] our DIT stage with full color-correction, and we have video playback. We’ve had a stunt driver drive it, so that we can chase a car doing 50 or 60, even through some of the stunt driving — so that we could be there and David could give direction to them from 10 feet behind, as if he’s in it.”

Rosenthal — who began his career as a cinematographer as he eyed directing — adds that “this is a very complicated movie” with a total of 1,900 setups. “[First AD] Richard Graves is an incredible tactician, which we need on a movie like this. He has helped me and Peter maximize our shot count, and shoot in the light and time of day that we want to shoot in. I think we’re doing really well — we’ve had a lot of luck and a lot of good planning.”

“Go to 1,280,” Flinckenberg says from his seat on the bus as he examines A camera’s capture of the scene in the glowing woods. “Go to 1,280,” digital-imaging technician Dwain Barrick confirms, as the ISO is adjusted. The two dolly-mounted cameras are rated at 5,600K and are recording at 23.98 fps.

Shot out of sequence, the scene takes place the night before the forest confrontation we witnessed earlier. Will has reunited with Samantha (Kat Graham), though he’s found her in the company of the doomed Jeremiah, who is none too pleased to see that Will is alive and well — and here. There’s an unspoken air of foiled plans as the trio sits around the fire, the flames serving as a dynamic orange key on the actors, while the slowly swaying 18Ks provide a contrasting turquoise sidelight and luminous backdrop.

The cameras move slowly along their tracks. A and B have been alternating between wides and tights as the crew captures multiple takes. Now A is on James and B is on O’Brien. The filmmakers make sure that a whiskey bottle is in frame. Flinckenberg and Lehtinen confer quietly, then change “this and that,” as the gaffer says — referring, we find out later, to the positioning of the 18Ks and the intensity and color of the Carpetlight-derived fill — and suddenly O’Brien looks perfectly sinister.

It’s Graham’s last day on the picture. She bids farewell as the actors complete their work. Flinckenberg supervises a slow rotation of the camera as it captures an upward shot of the trees, landing at just the right angle to catch a reflection of the fire on the leaves.

“Don’t forget a shot of the fire!” someone calls out. The night’s shoot thus concludes with the cinematographer on his hands and knees, leaning on a fallen branch and capturing the flames.

•••

Actor Forest Whitaker — who plays ever-disapproving patriarch Tom — completed his work on How It Ends shortly before our arrival, and stories of the moving-car work he was involved with on the production abound. Most often, we hear about the “bridge chase,” which begins when Will and Tom attempt a nighttime bridge crossing and their car is stopped by a local militia, whose piercing yellow headlights dominate the frame. The protagonists turn tail and attempt a perilous escape.

The car was “doing 90 and pulling 180s,” Rosenthal describes. The vehicle in question is what’s been dubbed the “Top Rider,” a silver 2018 Cadillac CT6, which has had its controls rerouted to an apparatus on its roof that includes a stunt-driver’s seat, as well as rigging to allow for an array of LED lights.

on the roof, as well as comprehensive rigging for cameras and lighting.

The production has in fact employed four Cadillacs throughout the shoot: one “untouched” and two progressively damaged to suit the story, which are used for objective shots, and the Top Rider — though it’s the latter that has been the primary tool enabling this production to shoot all of the driving scenes in-camera on real roads.

“That was a self-imposed mandate from me,” Rosenthal says. “From the first time I read [the script], I knew that in order to have this movie feel alive and authentic, and to have a kinetic vibe, I did not want to be on process trailers or a greenscreen stage, and I didn’t want to shoot rear-projection LED — all of which I’ve done, and all of which you can do effectively. But when I look at films that have that kinesis, like Mad Max: Fury Road [AC June ’15] or Drive [AC Oct. ’11], they figure out clever ways to put cars on the road with actors, and I just immediately started to look into the best ways to do that, and the Top Rider seemed like the most effective way.”

A decision was also made to enable remote shooting and lighting of scenes employing the Top Rider and other moving cars, which necessitated a system of wireless communication with a given car’s cameras and fixtures. “We did some testing and came up with the possibility of using the newest equipment and radio-transmitter technology,” Flinckenberg says. “[With four DMX universes], there was an amazing number of channels to control the light. We had this idea that we could be on the move, and the whole production team — the operators, the director, the producers — would all travel with the actors [via the production bus]. I felt like it was a unique way of shooting, while also keeping it as real as possible for the actors and interfering as little as possible with their work.”

Indeed, James offers that working with the Top Rider “enabled us to concentrate on everything that we should be concentrating on — the performance and the character. I think we were able to play with real reactions. When it accelerates, you’ll hear the engine burst into life, and then you’re turning the wheel in sequence with the Top Rider and stunt driver. It made it more atmospheric and more intense. There was reality there, which made it very tangible, and as an actor that’s really useful, and [helps one deliver] an even more real performance.”

In the Top Rider’s interior, two 9" x 25" Carpetlights, which Flinckenberg describes as providing a “quiet, soft light,” are affixed toward the center of the ceiling. Along the ceiling’s edges, above the windows, are 12 bicolor LED strips in an array designed by Lehtinen along with the show’s original board operator, Toni Haaranen — another native of Finland — who worked the first month of production. The strips are affixed with Velcro, to attach and detach quickly so as not to appear in frame. LED strips placed behind the dashboard pane — which was re-created by production designer Phil Ivey after the original pane was removed — were sometimes used as an eyelight. The wiring for the interior LED fixtures was placed behind the car’s interior panels, out of sight, as part of the vehicle’s modifications.

The Carpetlights and strips are “all separately dimmable from inside the follow vehicle,” Flinckenberg attests. “In earlier days, you would have to stop everything and add ND gels when the ambient light outside goes down.”

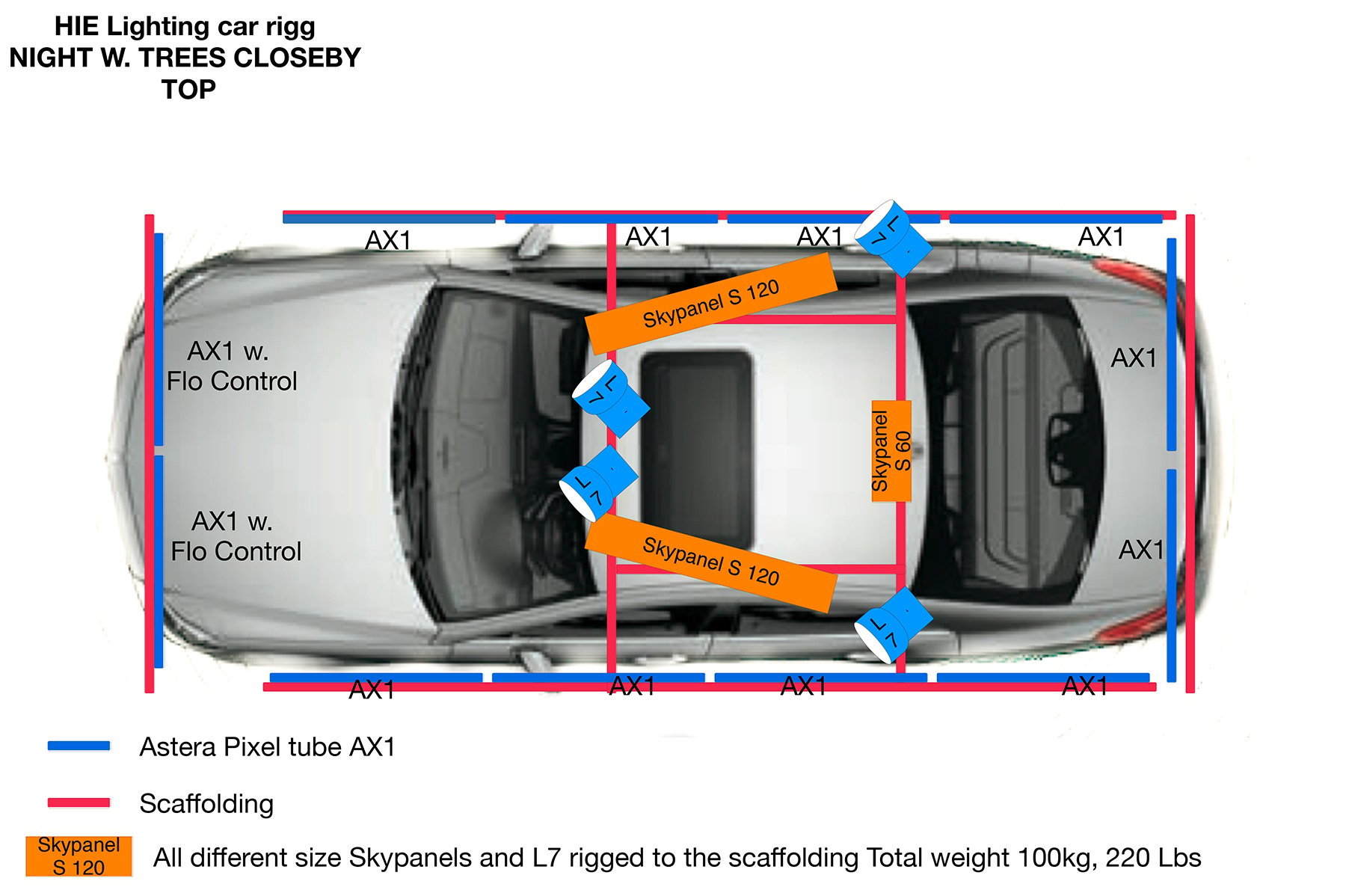

The Top Rider is also rigged for a wide variety of mounted lighting on its exterior. Astera AX1 PixelTubes are the most commonly referenced unit in this regard, when we chat with the crew. The battery-operated LED units, which take up most of the approximately 2,000 DMX channels, are primarily employed as chase lights on the car’s exterior to complement the production’s objective lighting.

Finnish dimmer-board operator Mia Kaariainen, who took the reins upon Haaranen’s departure, relates, “The tubes are taped onto the Top Rider rig and I do chases with them — [as well as] all kinds of flashes — to simulate shadow and light, and trees going by,” which she custom programs on the Dot2 console on board the bus. “Jani tells me beforehand how fast we’re driving and what the surroundings look like. There’s not much time to do the programming, and I’ll keep adding things on the fly. Every time we cut, I’ll do something else and show the gaffer. It’s constantly evolving, and quickly!”

To create such effects as forest fires and lightning and hail storms, the PixelTubes have worked in combination with SkyPanels and L7s, which were mounted to the Top Rider as well, while a series of Dinos — in addition to Lightning Strikes and 100K SoftSuns, both from Luminys Systems — “were placed along the road, and [Camtec’s] Color-Con [lens filter] was mounted on the camera,” Lehtinen notes. The Color-Con filter, operated via the dimmer board, allows for the adjustment of contrast and hue directly on the lens.

More generally, SkyPanels are sometimes rigged to the exterior for use both in lighting the interior from outside and aimed outward for lighting backgrounds — the latter of which sometimes called for L7s as well — which required the additional rigging of a small generator.

Flinckenberg and Lehtinen also speak highly of DMG Lumière’s SL1 Switch and Mini Switch LED fixtures, which were used primarily for interior scenes.

Remote camera heads are frequently mounted to the Top Rider, with their respective operators and assistants generally located on the bus. With its smaller form factor, a Mini Libra is used when shooting remotely inside the car. “Configurations vary because sometimes there are two people in the car, sometimes one and sometimes three,” Flinckenberg says. He adds that the production employs a standard Libra that can be mounted to the car’s exterior, in order to shoot remotely through “side windows, the windshield, or even from the back of the car. The Top Rider had points welded underneath the chassis, so the grips — headed by key grip Mitchell Holmes — could position the Libra and camera on many different parts of the car. One of the challenges was definitely to have interesting camera angles for different scenes, as so much of the movie takes place in the car.” Hard mounts are used with regularity as well, particularly when a C camera is employed.

“There were some moments where we had three cameras through the windshield, mounted on the hood,” the cinematographer continues. “For the bridge scene, for example, there might be three cameras on the car, and then one doing objective shots. A lot of planning, but it was fun.”

With a maximum communication distance of 3,000', Teradek’s Bolt 3000 TX/RX transmission system wirelessly handles the video signal between the cameras and the bus. “A huge antenna rig on top of the bus,” as Flinckenberg describes, relays the information between the vehicles. The production learned early on that the antenna array had to be periodically reconfigured, based on whether the van was following or leading.

“For wireless DMX transmission, we used two LumenRadio CRMX Nova TX2 transmitters on the bus, supplied by RatPac in Los Angeles.” Lehtinen says. “These transmitters are wired to special antennas on the bus roof beside the Teradek antennas. On the receiving end, we used RatPac Cintenna receivers on all the lights except on the Astera PixelTubes, which have built-in LumenRadio receivers.”

In addition to camera and lighting signals, Raucamp adds that the Libra heads require the use of their own remote system.

Using a two-camera scenario as an example, Barrick explains that the camera feeds are wirelessly transmitted to the bus and “pump through my system through Pomfort’s Live Grade software, and I display it up on the two 25-inch monitors for Peter and David. Then the video [which has had a LUT applied] goes back through to video-assist operator Tim [Davis], who’s at the back of the bus, and he then distributes it through to the focus pullers and to the other crewmembers that require the image — like the Libra-head operators and such.”

Davis explains that his work also includes “ensuring that there is a reference for every scene in the movie — keeping a record of everything. It’s very important for continuity questions. We can also do a quick edit for the director.”

Barrick notes that after he puts an ASC CDL “color workflow in place, those metadata files come off of my system at the end of the day and go into the bigger color-correction suite on the camera truck, where we run it through Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve at the end of the day’s shoot. I add the CDL values and do color matching based on that.” He adds with a laugh, “It’s difficult to color-match [between the cameras] on the fly with the mobile system, because things bump around and my colors change on me every once in a while.” Data on the camera truck is managed by DIT utility Calvin Henrion.

The final grade will be performed at Urban Post in Toronto with DaVinci Resolve by Swedish colorist Mats Holmgren.

“We feel like we’re right in the middle of the stunt,” Barrick says of working in the moving bus. “We’re in the action — we’re driving as fast as they are, we’re slamming the brakes the same time as they are, we’re accelerating, we’re turning corners very fast.”

Davis notes his appreciation for Efosa “Efo” Otuomagie, who drove the bus for stunt sequences. “That was one of the requirements I think we all agreed on — that if we want to be safe with [the bus], we should have a stunt driver,” Davis says. “And [Efo has] been nothing but safe.” Otuomagie also served as Whitaker’s stunt double.

On the challenge of pulling focus from inside a moving vehicle, Raucamp notes that although the production may need two or three takes to get the image right, Flinckenberg “doesn’t mind if there’s something that’s not completely sharp. He’s the first cinematographer I’ve ever worked with who says, ‘Sometimes getting it out of focus isn’t always a bad thing.’”

•••

Our second day on set begins in the afternoon light. Will has hitched a ride with a family in a worse-for-wear olive-green Jeep Wagoneer.

In the back of the vehicle is a United Rentals Honda Inverter EU3000i generator. The ceiling is outfitted with a similar array of Carpetlights and LED strips as the Top Rider. Two L7s are rigged to the front exterior, facing the windshield to light the actors inside.

Production sound mixer Tim Lue, who works in the back of the bus beside Davis — “Tim Audio” and “Tim Video,” as they’re known to the crew — tells us that the sound recorder is way in the back of the Jeep, and that it’s similarly stored in the trunk of the Cadillac for Top Rider scenes.

The A camera is hard-mounted to the front passenger-side window, capturing a shot of James and David Lewis (who portrays Jake). B Camera is behind James, mounted to an OConnor Ultimate 2575D head on a high hat affixed to an Arri 450mm/18" bottom-plate slider — all in turn mounted to an apple box on the floor of the car. B is positioned to capture both Lewis and, via a pan, his character’s wife (played by Charis Ann Wiens) in the back seat with their child (Juliette Hitchcock) on her lap. Lewis is doing the actual driving. “We used hard mounts because the road was in very good condition,” Flinckenberg says.

For this scene, featuring conversation between the exhausted travelers, the B operator and 1st AC ride along in the Wagoneer. It’s close quarters. Peterson notes that they’re “sacrificing balance and ease of operation for camera position. There’s no panhandle — you can just grab the camera [body] and manipulate it.” Howell has his Preston Cinema Systems wireless focus system in hand, and references his 1920x1080 5.5" LCD TVLogic VFM-058W monitor — the same one he uses when he’s in his seat on the bus. The camera is paired with a Hawk V-Plus 50mm close-focus lens, and captures at 23.98 fps, 800 ISO and 180-degree shutter at 5:1 compression, with white balance rated at 5,600K.

The production rearranges the setup to place B camera behind the driver seat for a few shots of James. The cameras and all visible interior rigging are then pulled so the crew can capture shots of the front of the moving vehicle — accomplished with a three-car caravan comprising the bus in the lead, then a modified Ram 2500 V10 Magnum camera car, and the Jeep following behind.

Lehtinen tells us that visual effects — provided by Mr. X in Toronto — will be adding dust to the air for an appropriately apocalyptic look. He adds that a Russian Arm has also been used extensively throughout the production for vehicle tracking.

The Jeep is ushered off. Production shoots some quick additional footage of James running in the forest while the crew sets up the Top Rider at a breakneck pace. They pull the back seat out for remote-head and camera placement, while Kaariainen and others Velcro-in the Carpetlights and LED strips. The 16-pixel Astera tubes are affixed to piping rigged to the car’s exterior. We steal a glimpse of the driver-side interior and note the peculiar lack of gas or brake pedal. The car’s stripped-out trunk is packed with a panoply of wires and transceivers.

“Juha Virtala, lead lamp operator, was in charge of handling the Cadillac’s interior fixtures,” Lehtinen says. “He did a great job and was present for the whole production.”

At lunch, we chat with Dano Neil and Casey Markus from special effects. Out of the 60 or so features he’s worked on, Neil notes that this is “one of the most cool, chilled-out vibes on a show — and that comes from the top down. Not all shoots are like this. When they’re relaxed at the top, it spreads to the whole crew.”

It’s around 9 p.m. and the crew is back on set. Lehtinen asks Kaariainen to demonstrate the Astera chases, resulting in a display of blues and yellows on the stationary Top Rider. The gaffer tells us that Kaariainen has designed the chases to complement two 18K Arrimaxes on 85' condors and one Arri M90 on a crank — each gelled with Storaro Yellow — that will light the road through the trees. “Rigging gaffer Russ Faust and his crew did an amazing job with so many remote and complicated locations,” Lehtinen says.

We strike up a conversation with C-camera and 2nd-unit operator Matt Schween, who tells us that 2nd unit has shot outside of southern Manitoba cities Brandon and Carman, as well as in the Pembina Valley, a rare hilly region of the province. Tomorrow they’re off to capture some drone and car footage.

We board the bus for the Top Rider’s final performance in the movie. The setup is an addition to footage captured earlier in the production, for a scene in which Will, Tom and Ricki (Grace Dove) drive toward an immense fire. The specific angles the filmmakers need are from the front and rear right-hand seats, in order to capture a trail of “refugees.” With belongings in hand, the displaced survivors — played by a sizable group of background actors — walk along the side of the road.

Between takes, James sprays his face with a water bottle to add some beads of sweat. The yellow light of the 18Ks, M90s and car-mounted PixelTubes, as well as the illumination of the Top Rider’s interior LEDs, give the actor a noir look that is further improved when Flinckenberg requests that the dashboard panel light be brought down.

The A camera is affixed to a remote Mini Libra mounted to the front passenger seat of the Top Rider, while Peterson operates B cam — in person — from the back seat on the same side. Working remotely from the bus, Finlay is at the Libra wheels while Raucamp and Howell pull focus. The A camera is paired with a 35mm Hawk V-Lite, and B with a 40mm Whitepoint.

Upon watching A camera’s skillful remote pan from the refugees through the front windshield to a view of them through the driver-side window, followed by a focus on Will’s profile, Rosenthal calls out, “Roger, that was good — that’s the idea!”

We learn that an L7-C mounted to the front of the Top Rider is augmenting the car’s headlights, further illuminating the refugees, and that Schween and C-camera 1st AC Greg Nicod are off the bus, capturing additional footage of them.

The Top Rider is used once more, for a scene in which the Cadillac stalls and conks out — and Will has a meltdown that’s been a long time coming. Then it’s a picture wrap for the beloved custom build. “One of the greatest Top Riders of all time is going out to pasture,” we hear someone say. Stunt driver Patrick Mark descends from his rooftop seat and hugs everyone goodbye. With just a week of production left, the parting portends the end of this particular world.

You'll find further coverage on How It Ends here.