Reframing a Murderer: Making Monster

Steven Bernstein, ASC looks back on shooting director Patty Jenkins’ feature debut, based on the life of serial killer Aileen Wuornos.

When he got the call that director Patty Jenkins was looking for a cinematographer to join the scrappy independent crew of the intimate true-crime drama Monster in Florida, Steven Bernstein, ASC could not have been in a more radically different filming environment. He was finishing up shooting the action unit on the crime feature SWAT at the time. “We had 23 cameras set up right then on the 2nd Street Bridge,” he remembers. “We were crashing a jet and we had just blown up the front of the L.A. Public Library. It was sort of the testosterone dream — but that is always the problem for anyone in film. The things you think you want aren’t always the things you actually want. I looked around at all the equipment and the huge crew and I thought, ‘Well, this surely is the dream,’ but I felt absolutely spiritually empty inside. No disrespect to SWAT — it was a great movie.”

Bernstein read the Monster script at the behest of producer Clark Peterson, expecting to turn the offer down. Instead, he decided to leave SWAT and travel to Florida, where the crew was already gathered and production was waiting. Bernstein was immediately taken by the script: “One of the hardest things to do as a writer and as a director is to create that empathic bridge with the character. That's one of the things that Patty understood so well. It was almost Hitchcockian, the intuitive approach to the script. You think there's no way that a serial killer could be sympathetic; but of course, the greater philosophic conceit is, if, in the end, she is sympathetic than all of us are worthy of sympathy.”

“It was incredible how on Monster, her first movie, Patty was able to stand up to forces that were trying to get her to compromise her vision.”

— Steven Bernstein, ASC

There was no time to prepare before the shoot. Production was fraught, having already shot two days of footage with a cinematographer who was no longer attached to the project. Bernstein had to hit the ground running in Florida. Bernstein credits his collaboration with Jenkins and with producer-actor Charlize Theron for the ability to keep the project on track. Arriving on location, he spent time immediately watching through the previous footage with Jenkins and Theron: “If you can maintain, as Patty and Charlize did, and as they taught me, a creative integrity, and do things that are greater than yourself and greater than specific and immediate material return, then the reward ultimately is much greater than any else that you can get.”

While Jenkins had never directed a feature before, she knew exactly what film she wanted to make. “It was incredible how on Monster, her first movie, Patty was able to stand up to forces that were trying to get her to compromise her vision,” Bernstein says. “She did it in a Buddhist-type fashion, never raising her voice, but was immutable. She couldn't be altered. She was going to do what she was going to do, whether they wanted her to do that or not — but she did it in a gentle way. She would listen to people; she would take advice. She would also listen and not take advice.”

Working with a director with a distinct sense of vision was an asset that Bernstein does not overlook. As a writer-director himself, he appreciates a collaborative process that allows for clarity and creativity. Within that space on the set of Monster, he was able to implement tactics to make the shooting schedule possible: “There was the insuperable obstacle of shooting a film that needed three times the amount of shooting time than we had. But when we discussed it, we decided to adopt a methodology that allowed us to shoot very quickly. It changed forever the way I shot movies and changed forever the way I directed movies and the way I write movies.”

In order to make their tight schedule, Bernstein decided to eschew traditional marks for actors.

Instead of blocking and lighting for the rehearsal marks of the talent, Bernstein decided to move the lights to the talent, no matter where they went. As he recalls, “I thought, ‘What if we let Charlize go wherever she wants?’ Rather than her moving to our marks, we move to her even with the key light. So I took a paper lantern, with a radio link to one of the electrics, and a second, and a third and a fourth paper lantern. I would then put the camera on my own shoulder and the camera would move with the focus puller.”

Working with a manual follow focus and moving marks was not easy, but Bernstein tried to create an environment for success on the camera side as well as that of the actors. “The marks were hidden in the ground, so that the AC could change the focus as [Charlize] changed her distance to the camera. Of course, if I moved forward, he would then have to estimate the distance, but because everything was marked out, we could hold focus, and the lights could move with them. She'd go wherever she wanted. It became this incredibly fluid thing. We went from 13 to 15 setups a day to, one day, we did 67 setups — and the performances were magnificent.”

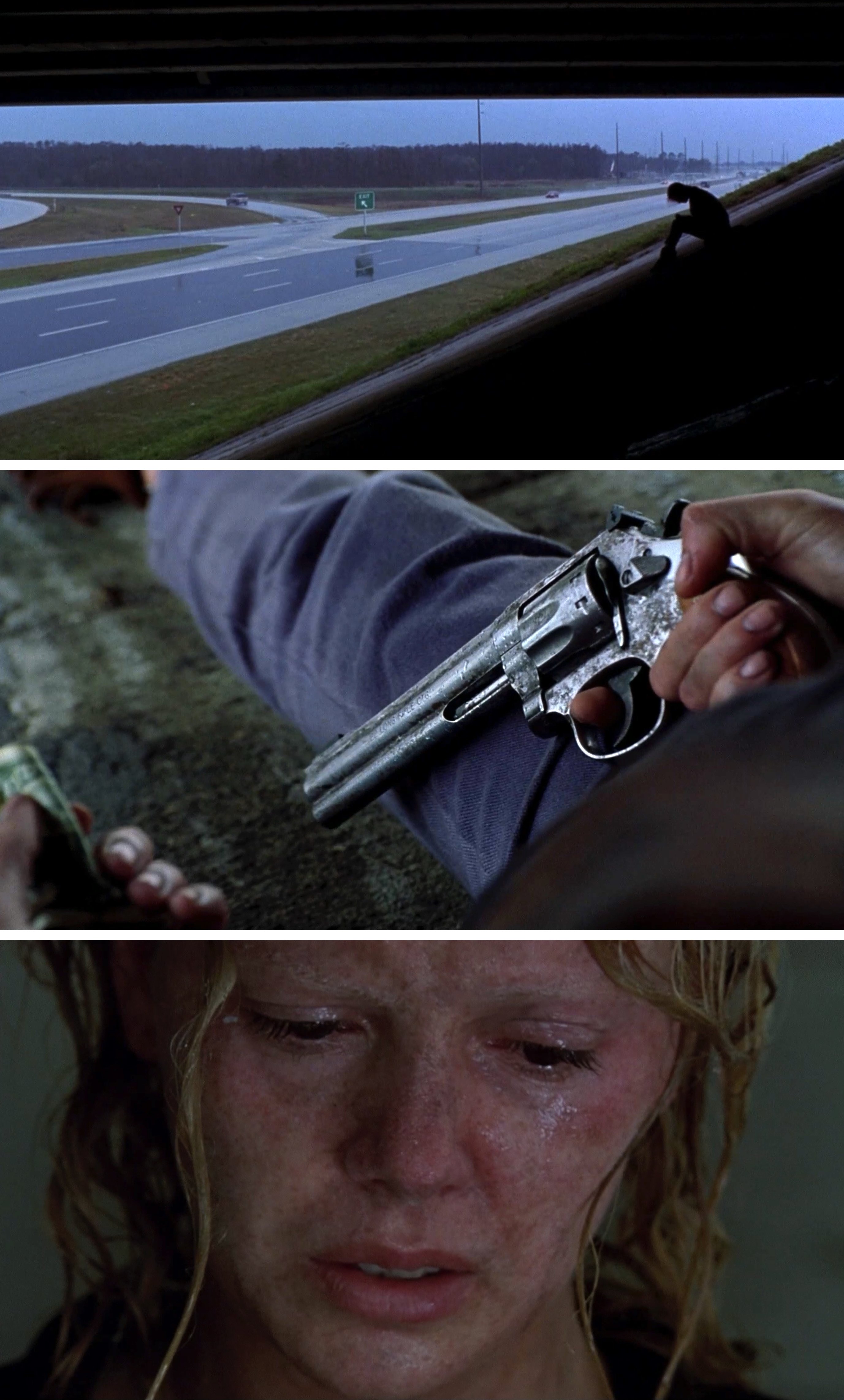

It was important to allow space for performance, as the film balances the line of creating empathy for Aileen Wurnous, the serial killer, while not justifying what she did: “The murders were very important. We didn't want to imply that the murders weren't horrible. Patty wasn't justifying the character, she was simply exploring primal human need. So we would play the full horror of those scenes. We'd go on longer lenses and the camera will become more active to show the violence. The colors, if you look at the night scenes, were more intense.”

While soft lighting prevailed in much of the film, Bernstein used harder lighting in some of the murder scenes to create a sharp distinction.

Bernstein played with color throughout the film, leaning into what was naturally occurring on location: “We became very interested in the patina of the buildings in Florida. It becomes an objective correlative of something emblematic of the moral decay of the characters. It’s pretentious, but that's what we felt. By using very soft lighting and by intentionally under exposing and printing up the film stock to build in more grain, and also reduce color saturation, it magically transmogrified the images we were looking at. It became emblematic of the ideas we were trying to represent.”

Shooting on the Panavision Vision G2 with Kodak 500 ASA film stock, Bernstein found himself utilizing Tiffen Soft Contrast filters to lean into the desaturated look: “They don't build up the low end too much, so you don't get that sort of washed out look you get with low-contrast filters. The refraction within the filter is such that it reduces color saturation, but it doesn't reduce the acutance. So the image would still be relatively sharp, but the colors would be desaturated. And your black level integrity would be maintained. So they were spectacular. I was obsessed then, as I still am, with the diminishing of color saturation. Whenever you reduce saturation, I think you get a greater level of verisimilitude to it.”

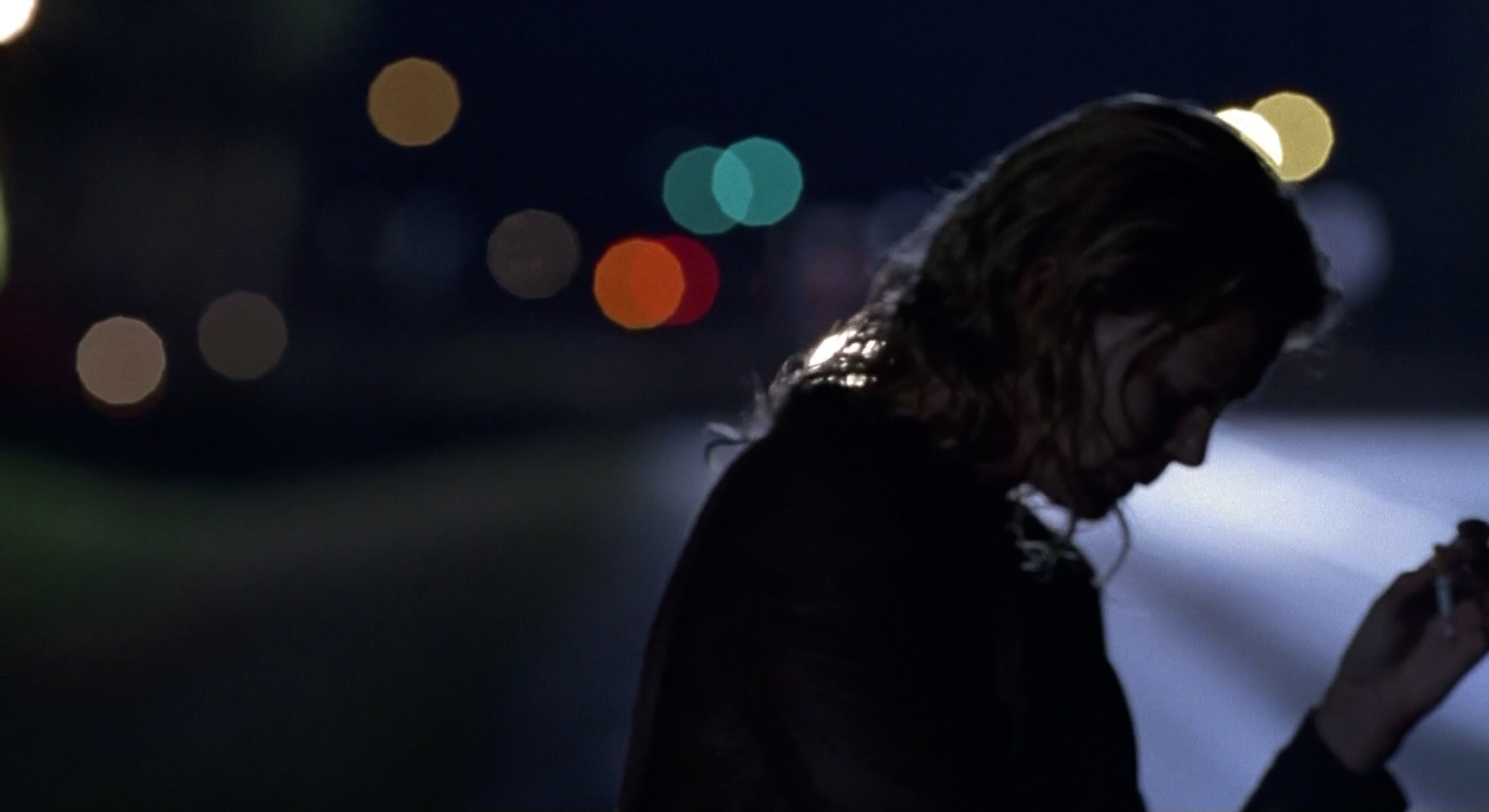

The modest budget of the film required creativity in lighting, especially outside at night. Instead of this being an impediment to Bernstein, it allowed for artistic lighting choices: “If there's something beyond Haiku, it would be cinematography — we say even less and we mean even more.”

The hint of something in the background became a key trick to utilizing a sparse lighting kit for large night exteriors, “I've learned that lighting is a bit like painting. The suggestion of an idea is very often enough to have the audience believe that idea. So, when you've got a low budget and a big night exterior, if you light seven or eight trees in the background, and then have some backlight on your subject, as well as a low angle soft key on the subject, if the contrast between the foreground and background isn't too great, the background will hold.”

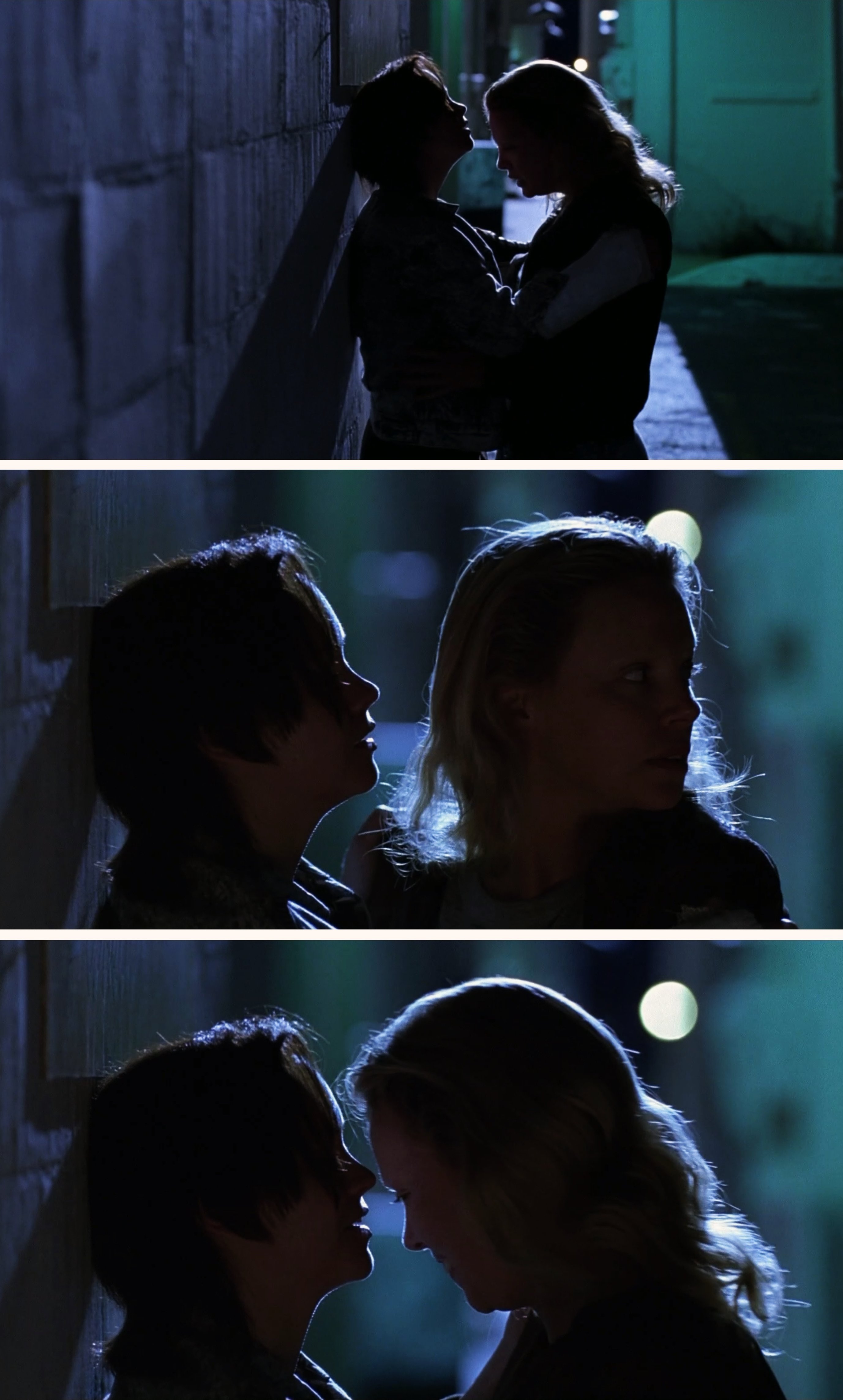

This style of lighting worked to great effect in the scene in which Christina Ricci and Charlize Theron’s characters kiss for the first time. “We took one backlight, a 5K, as high as we could, just out of shot, and drifted a little smoke through,” he describes. “The other thing I'm very interested in besides soft lighting is lighting from below, which I borrow from Renoir. I am fascinated that everything in Renoir was lit from below. It's very interesting psychological impact on the audience because we don't anticipate light coming from below. Instead, it seems as if the characters are iridescent from within. We used a soft 2K light with double diffusion and a bit of shower curtain from beneath them. But at a very, very low level about three stops less than the backlight. It was magic, and we did the setup in 10 minutes.”

Looking back on the impact of Monster some 20 years later, Bernstein is emphatic about the artistic influence the film continuous to have on him, “Every one of those films that I've directed, and in my writing, and all the cinematographers who work for me, have, because of me, been influenced by Monster. Patty has had a profound influence on my life. She taught me a lot about being a better person, and that you can lead with strength without being combative. She is incredibly generous and kind but doesn't sacrifice her vision and those things are not mutually exclusive. She also taught me about things I should have known already about creative integrity.”

Bernstein’s work as a cinematographer can be seen in Kicking and Screaming, Mr. Jealousy, White Chicks and the series Magic City, for which he was nominated for an ASC Award in 2014. He has also written and directed the features Decoding Annie Parker, Last Call and GRQ.

You can follow him on Instagram here.