To Be King: Making The Lion King

Cinematographer Caleb Deschanel, ASC and visual-effects supervisor Robert Legato, ASC team up in virtual space to shoot the photo-real reimagining of an animated favorite.

Unit photography by Michael Legato and Glen Wilson.

All images courtesy of Disney Enterprises Inc.

Society members Caleb Deschanel and Robert Legato sat down at the ASC Clubhouse on a Saturday morning in May to discuss their shared adventure that was the making of Jon Favreau’s The Lion King, a photo-realistic reimagining of the classic Disney animated feature. As cinematographer, Deschanel employed revolutionary virtual-cinematography techniques; as visual-effects supervisor, Legato offered Deschanel the benefits of the many years he spent pioneering and then refining those techniques, starting with his work on James Cameron’s Avatar (AC Jan. 2010) and then Favreau’s previous feature, The Jungle Book (AC May ’16).

While The Lion King will undoubtedly have a profound industry-wide impact as it advances new methods of filmmaking, it will also further the paradigm first put forward by the production of Jungle Book, wherein the equipment, processes and philosophies that so-called “traditional” filmmakers have employed for decades are applied to animated imagery through a virtual-production workflow.

ACsat in on the filmmakers’ conversation and offers this edited transcript of their discussion.

Caleb Deschanel, ASC: For me, going to Africa [on a preproduction research trip organized by Favreau in 2017] was the thing that solidified my interest in this project. When we were there, I fully realized how the film pays tribute to the vast landscapes in Kenya and the wildlife that is now, sadly, under duress. We also got to film at [Disney’s Animal Kingdom theme park] in Florida. There, the lions were beautiful references for [the lead lion characters].

Robert Legato, ASC: They were such perfect animals — beautifully taken care of. We got some really beautiful footage. But when we went to Africa, that’s the real stuff. Those lions were mangy and rough.

It wasn’t a huge leap to come up with [the sequence for The Lion King’s famed theme] ‘The Circle of Life’ there. We were able to see that concept firsthand every day in Africa. It was spiritual to some degree, and it inspired us even beyond [the specific research and reference materials that were acquired].

Deschanel: All of those references really do affect your subconscious. I wasn’t hired by Jon because I’m some kind of tech wizard — I was hired because I’ve spent about 45 years of my life filming reality. Going to Africa and really spending time there was very important for emulating locations, skies, textures and so on.

Legato: Producer Jeff Silver really wanted to go to Kenya when I first joined. Every single shot and pixel [in the movie] is manufactured, so having a reference for what it really looks like helps answer a lot of questions when you go to re-create it. You need something to root it in reality if you want to replicate that reality. And we found places that inspired us. I think the whole trip got stuck in our mental computers and then spilled out when we were making decisions [throughout production].

You can have all the tools, but you still need the ‘taste’ in order to apply and use them to create something that is beautifully photographed and rendered in a dramatically told movie. Someone of your caliber and experience was therefore the perfect ingredient. My journey has been to take these technical elements and ‘remove’ the technical portion and bring it back to an analog way of thinking. How do you set up a dolly shot? What lens do you use? What lighting do you select? How do you stage it? We needed a real cinematographer to impart artistry and wisdom.

Deschanel: Unlike a traditional live-action production, however, Jon would work out the animation with [animation supervisor] Andy [Jones] before we would become involved, and then he would bring Rob and me in [with production designer James Chinlund] to review for blocking, to figure out how we were going to shoot it. We would make suggestions based on what we thought it was going to look like when we filmed it — for example, to change the course of the way the animals were walking, or lower a hill, and so on. It became a really valuable part of the process that inspired the design of the filming.

Andy and his team would finish the animation based on the discussions, to be ready for filming. Early on, the animation and the sets were quite crude, with animals walking through rocks at times, but as we went on, it got to the point where there were real, sophisticated performances, and the sets were much more realistic. It was a pretty complete rendering of the scene — lacking the finished fur, perfect movements, real trees and rocks — and was good enough to read the emotions and feel the surroundings.

[This yielded] a gigantic digital file [featuring] the performance of the characters and the setting — [with] dialogue and songs all prerecorded and synced with the characters in the virtual world.

Legato: It’s a big master file that has the animation and the setting in 360 degrees, and it’s ‘waiting’ for the virtual camera and virtual lighting — and then we walk into it in VR and start to become specific. ‘Put the sun over here, put a rock in the foreground, and this is where I’m going to photograph with a 50mm lens.’ It becomes viewable [on a traditional screen] when you enter the program and photograph it. You have to think of it as a live-action set — you’re staging the master scene, which is contained in the file, and then picking apart the scene throughout the day by relighting and reshooting various moments for close-ups and multiple angles. We shoot with a single camera — you don’t need multiple cameras, because the action is going to be repeated exactly the same way each time, so it’s easier just to move the camera.

Deschanel: [When starting work on a scene, Sam Maniscalco, lead lighting artist from visual-effects studio Moving Picture Company (MPC),] would look at it, and based on where we were in the story, begin to light it — considering the time of day, the location and so forth. We would also pick the sky to go with the scene; we needed to consider the mood, and we had 350 skies we could choose from. We would find the right clouds and sky color, and then adjust the sun to wherever we wanted it to be.

You might think we would just put the sun where we wanted it and leave it there every day — but, in fact, that never happened. We moved the sun on virtually every shot.

Legato: That’s also something that makes the movie look like it was conventionally photographed. That so-called perfection of having the sun stay in one spot — besides the fact that it doesn’t look great shot-to-shot — is something you would only see in a computer-generated movie.

That’s the ‘taste’ factor that makes this method transcend beyond a technical exercise. It might be mathematically correct to place the sun where it would actually be, but it’s not artistically correct — so you do something else to make the shot work. That’s why we brought you in, as well as other people who do these things in the real world.

Deschanel: One of the biggest challenges we had in terms of lighting was that for scenes in the deep, dense Cloud Forest, the sun wouldn’t get through the trees. So we’d just start taking out trees, one at a time — sometimes hundreds of them — until we got the light the way we wanted it. Since the location was going to be built again in a more sophisticated and detailed way at a later point [by MPC in London], we had to communicate our intentions to MPC so the look and feel of the lighting in the final version would be consistent with the lighting we created.

Legato: The lighting process is similar to that of live action, except the final nuances [are realized] afterward. The lighting was determined with the Unity [rendering engine], and you knew the light direction was correct, and how it would affect the drama when it was finalized, but you only saw it properly lit some time after you shot it. [Filmmakers who shoot in this kind of environment] have to understand that in advance.

Deschanel: I think one of the really great things about Rob is that he knows how to use all the visual tools — [such as] Cinema 4D for lighting, Resolve for color adjustment, Avid for editing, etc. Instead of just describing an idea, he will put together a mockup to show how a sequence will evolve. He can show the director what we are intending to do. Not just talk it through, but actually show it to him.

Deschanel: The movie feels very realistic because the animals look so real — and because it was filmed in a way that ‘senses’ the hand of the filmmakers. The way the camera moves, the dolly work, everything. There’s the sense of a human observing and following what is happening.

I think there is something about feeling the human touch behind the camera, not just for the sake of classic filmmaking, but because we as human beings want to feel that some person is guiding us. I think that is the key to the whole thing.

Legato: Making it feel like shooting a typical movie was [assisted] by the [NaturalPoint] OptiTrack system. [Ed. note: See sidebar below.]

Deschanel: It was quite amazing. What was supposedly the camera was, in actuality, a [physical] representation of a camera that captured action taking place in virtual reality. We had a 25-foot-square area covered by OptiTrack, where we could maneuver the camera either handheld or on a Steadicam. The dolly and the crane, however, were encoded to read where the camera was on the track or at the end of the crane arm, so there was no need for OptiTrack.

We had a [physical] dolly on a stage, but we didn’t have a [true] dolly grip for a while. Don’t ask why! There’s a real artistry to moving a dolly — a ballet, a dance — and the person doing it needs to understand how to move effortlessly with the characters. I was faced with the realization of just how special that skill is. So we brought in a true, experienced dolly grip. It was the same thing with focus. At first, focus was done by the computer, but it never felt right to me, so I brought in my regular assistant, Tommy Tieche, and he made it look like what you are used to seeing in a live-action film. You might think it’s not important — but you can feel the decision to change the focus from one character to another just at the right moment, with just the right feel to give it the human touch we are used to seeing.

Guy Michelletti lasted the longest in a long string of dolly grips. Most of them would last a week or so and then want to get out of there. We had one piece of 20-foot-long dolly track — what fun was that for a dolly grip who wants to pull out wedges and apple boxes to level 100 feet of track over rough terrain?

Legato: [The distance the camera traveled in the real world could be multiplied in virtual space.] Humans are adaptable, and everyone soon got the hang of it. If the operator took one step that was a virtual step-and-a-half, he could mentally compute it based on what he saw in his viewfinder. It’s remarkable that we could do all this, and then start learning the mechanics of it, and make that part of the art form.

Deschanel: The tools we had — the dolly, the crane, the fluid head and the gear head — could be repurposed to do something other than what they were supposed to do. Once they were encoded, that coded information could either be a pan or a tilt on a dolly or a head, or you could repurpose it to move an animal a little bit one way or another, or we could tilt up and that would lift the camera in the air like the arm of a Fisher dolly. If we were using the gear head to pan and tilt the camera, that freed up the fluid head to be repurposed to raise and lower the camera as it dollied. It was a wonderfully complex dance of fitting all these pieces together so that we could film in the best way.

It’s hard to explain how similar this process is to [traditional cinematography], but it is. When you are operating, it’s as if you are looking through a camera at the same kind of image you’ve always looked at — not an optical image as in the old days of film, but a video monitor, the way you shoot with a digital camera.

Legato: The question we would ask ourselves was, ‘How would you capture this if you were shooting the movie for real?’ For a big, wide aerial shot [of Zazu, a bird character, midflight near the start of the movie], you would use a drone. And what’s the best way of imitating something? It’s to actually do it. So we got a [consumer drone system] and a real operator, who was also a helicopter pilot, and we set up a virtual path for him [inside the Playa Vista virtual-production stage].

We asked him to go past a tree, and he knows [that in real life] you would have to give it a pretty wide berth of several hundred feet before you need to turn, because you can’t turn on a dime [like you can] with a computer. It created a very cool shot for us, and it felt conventionally filmed. That is part of the psychology of it, that it continually looks like something you have either seen before or can imagine would look that way. You ‘believe’ they used a real camera to photograph it.

Deschanel: Overall, it was a very organic transition for me. Yes, this process is expensive right now, but that’s like any developing technology. As it gets more accepted over time, and other tools emerge, it will become cheaper and easier. Everything that is developed in terms of filmmaking technology ultimately depends on having artists who know how to take advantage of it — and it is those artists who advance the technology and make it into something we will regularly use.

Legato: Take electronic editing — people were firmly opposed to it, right up until they started doing it and realized it was actually pretty easy.

Deschanel: I really felt that was the case here. I was still doing storytelling. Storytelling involves getting emotion across, and now we have the ability to do it with a different set of tools and in different situations. I think that is what we mean when we say we are doing ‘traditional’ filmmaking here.

Additional reporting by Andrew Fish.

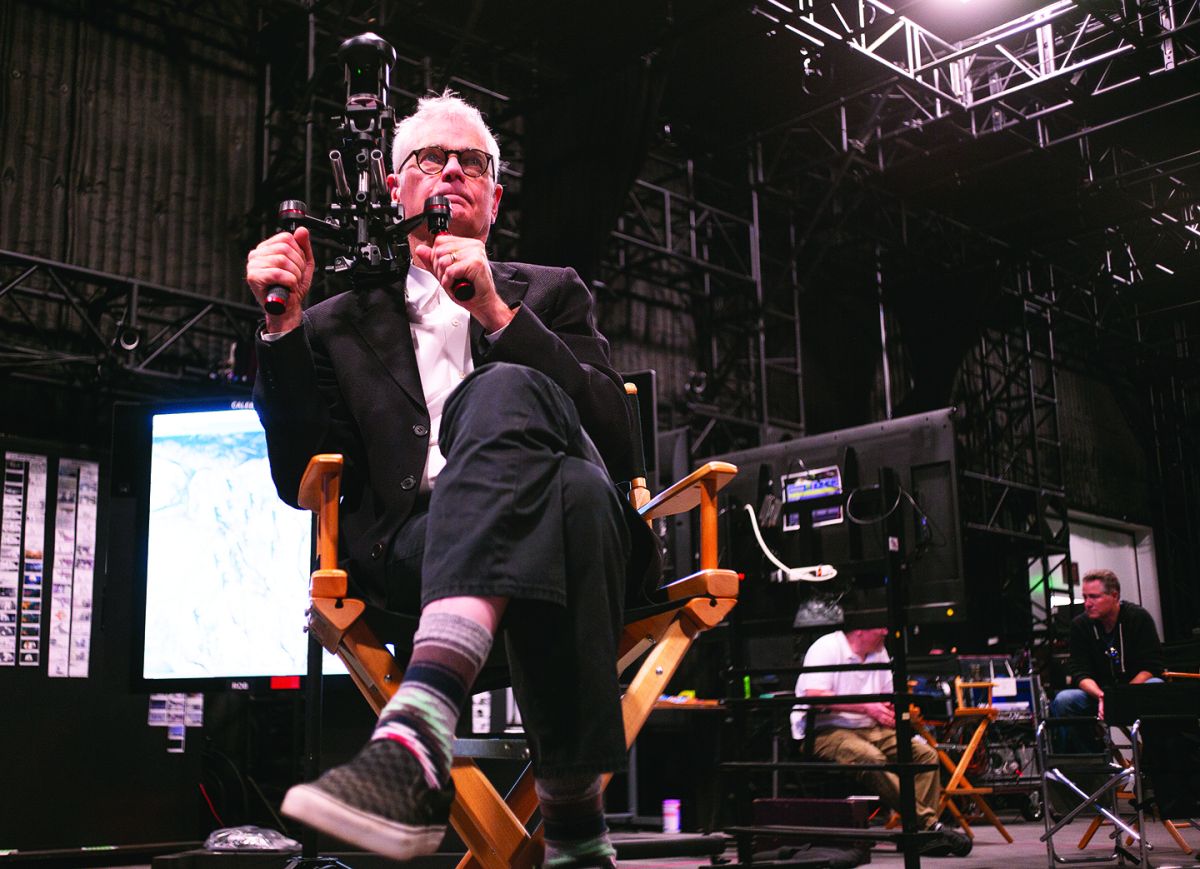

![The Lion King’s system of virtual capture allows for the overlay of movement elements, which Legato compares to “music that you’re overdubbing. For example, if we loved what [operator] Henry Tirl did with his delicate Steadicam choreography, but the composition wasn’t exactly right, then we could ‘steal’ his move and let Caleb operate over the top of that — we could remove the original panning and tilting and add Caleb’s. You can just separate it out, so one element is prerecorded and the other one is operating remotely.” Alternately, he adds, after a given shot, “we might say, ‘let’s erase the focus pull, replay the recorded shot, and then have 1st AC Tommy Tieche do another take of it’ — without having to reshoot everything just to do another focus take. It’s literally like visual overdubbing.”](/imager/uploads/76369/Lion-King-7-HenrySteadyCam_InAction_L1002558_6c0c164bd2b597ee32b68b8b5755bd2e.jpg)

Shooting in the Ether

Detailing virtual-production techniques and methods fit for a King.

The philosophy behind The Lion King’s virtual methodology was that it would allow a live-action director of photography to employ traditional filmmaking techniques with a virtual camera, virtual lenses and virtual lights — thus meticulously emulating real-world cinematography inside a computer. The design of the virtual-production workflow and toolset was led by visual-effects supervisor Robert Legato, ASC. As virtual-production supervisor Ben Grossmann, at virtual-reality production company Magnopus, notes, “The Magnopus team and I worked under [Legato], and we provided the software, the hardware, the design and construction of the stage, and the operations.”

Inside their production-volume space at a warehouse in Playa Vista, Calif., the filmmakers plotted specific shots, relying on detailed animated 360-degree “master shots” — created by MPC under the guidance of Adam Valdez, visual-effects supervisor at the company — and processed into the virtual world via a custom-developed suite of software that employed the Unity graphics rendering system. There, the filmmakers were able to join forces, videogame-style, using an off-the-shelf HTC Vive virtual-reality system, tracked using Valve’s Lighthouse VR tracking software. For high-precision tracking, the filmmakers used US Digital encoders, which, Grossmann attests, gave them “insanely accurate data [derived from on-set] hardware systems like a crane, dolly, fluid head, alpha wheels and focus wheel.

“Once all the equipment was set up, we had the entire camera and grip package attached to a modified drone controller with a joystick and a lot of knobs,” Grossmann describes. “This allowed Caleb to pick the entire camera package up together and move it around on the set if he needed to make an adjustment. It also allowed him to control the zoom and other standard camera controls. An attached touchscreen let him change the gears on the wheels, the speed of performances, and let him drop camera marks so that he could go back to them whenever he pressed a button. It also allowed people in VR to see where he wanted the camera to go when they were operating — instead of having a taped red ‘x’ on the floor as a mark, a grip could be in VR moving the virtual camera towards a ghosted copy of the camera that Caleb had placed, so they could hit their marks.”

The production also employed NaturalPoint’s OptiTrack sensor system, which allowed the filmmakers to record even the slightest nuance of the professional operators’ movements with their non-encoded equipment. “Essentially, the next generation of motion capture is an advancement from reflective balls to an LED emissive camera system,” Grossmann explains. “By incorporating over 60 integrated cameras — a combination of OptiTrack Slim 13 and Prime 17W units — in the ceiling truss, we vastly increased the size of the volume in which we could operate. Combined with the ability to dynamically scale the volume to fit the [virtual world] in which we were operating, drones, Steadicam, and large-scale handheld shots became possible.”

According to Grossman, the virtual camera was modeled after the large-format Arri Alexa 65 camera system that Deschanel and his colleagues took to Kenya to record reference elements. Pixel ratio and sensor size for their virtual camera “was cropped-in slightly from the full [Alexa 65] sensor to standardize the video-delivery spec between reference, capture, editorial, delivery from VFX, and eventually projection,” Grossmann adds.

He further notes that the filmmakers modeled all their lens calculations after Panavision 70 Series cinema lenses, which had been supplied to the production for the Africa reference trip — including 70 Series 28-80mm (T3), 70-185mm (T3.5) and 200-400mm (T4.5) zooms, and 14mm and 24mm primes. “We calculated both vertical and horizontal field of view based on the exact sensor size of the [real] camera, using data captured from lens-profiling sessions with actual lenses,” Grossmann explains. “Using that data plotted on a line graph, we were able to create a formula that could calculate the exact field of view for focal lengths that don’t exist.

“We even modeled the camera and lenses in 3D so that when you were in VR, you could see the exact camera as it would be in real life, with the correct lens on it. We did this so that an operator in VR could look over at a camera and see what lens was being used.”

Virtual-production producer A.J. Sciutto of Magnopus adds, “The virtual representation of the light was modeled after true Arri cinema lights, complete with barn doors and a lighting stand. The values of those lights [could] be adjusted in real time; by changing the color temperature, we could mimic the light coming from different sources, and we were able to adjust intensity on those lights with a range of 150 watts to 20,000 watts. [The light’s spread could also be widened with the virtual barn doors] to flood the scene or narrowed when focusing the beam to a spotlight.”

The filmmakers emphasize that the ultimate significance of this methodology was that it made it possible for Deschanel and his collaborators to design and execute the camerawork in a familiar way. “This meant they were drawing on decades of experience and instinct,” Grossman attests, “rather than standing over someone’s shoulder at a computer and looking at the movie from the outside.”

Deschanel admits that the Lion King virtual-production method initially gave him pause. “But it didn’t take long to feel comfortable,” he notes. “The tools were so familiar in terms of the way this process was designed. Originally, I was a little hesitant in agreeing to do this project, mainly because I had a feeling I would be getting myself into something that was going to be incredibly technical and very nerdy. But then Jon Favreau explained that he very much wanted the movie to look like a live-action movie or a documentary. And in the end, the ‘reality’ of the movie comes from a combination of the incredibly realistic animation — which is extraordinary, thanks to the work of Andy Jones and his team, and MPC — and the style of filmmaking. We had to painstakingly imitate real-life filmmaking.

“It was impossible to tell this story exclusively with long lenses in the virtual world, for instance,” Deschanel continues. “We had to become intimate and close with the animals — and how do you justify that when the animals are dangerous and wild? This was definitely influenced by our experience in Africa, where some of the lions came within minimum focus at times. And, of course, by films like Fly Away Home [AC June ’97], where we were warned that the helicopters could not get closer to the geese than 500 yards. In the end, the birds got used to the helicopter, and the animals in Africa didn’t seem to care about us — at least at those moments.

“What you don’t get in the process [of filmmaking in the digital world],” he adds, “is the serendipity of a rainstorm, or the sun peeking under the clouds, or an animal suddenly charging — the things you get when you film for real — so you have to go into your memories of all the places you have been in the world, and all the films you have done, and the experiences you have had. You draw from that to put yourself into this world and create that reality. Eventually, we learned to create some of the surprise with the way we set up the shots or maneuvered the camera in the virtual world.” — Michael Goldman

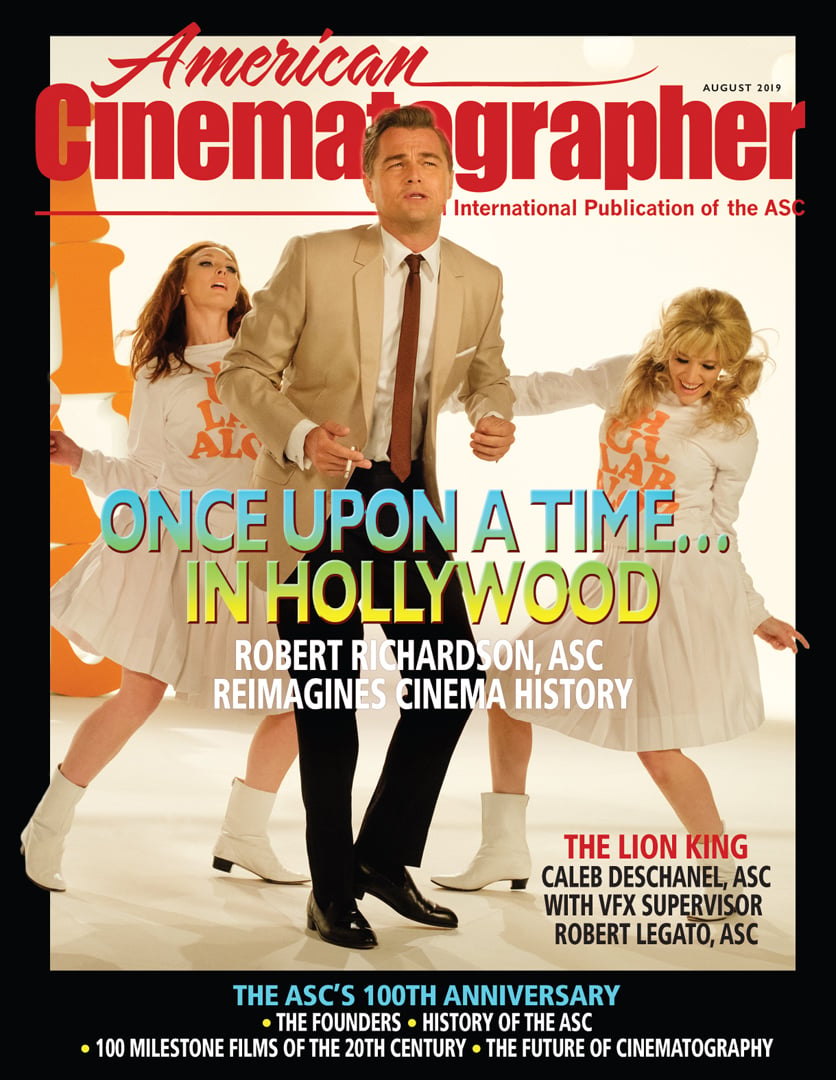

![Legato, Deschanel and Magnopus virtual-production producer A.J. Sciutto observe the action. Legato notes that VR goggles and controllers enabled the filmmakers to explore the virtual set — in order, for example, to find proper camera angles, or to determine and virtually mark such elements as the appropriate positioning for dolly track — but when it came time to execute the shot, most of the camera crew removed the goggles and used the real-world monitors.

Some notable exceptions included instances when Legato would operate a zoom, or Tieche would pull focus, and it was helpful to see both the camera and subject to determine the timing and measurement of the lens adjustment. Or, Legato recalls, “for the stampede [where the animals] are going [toward] the cliff — I was essentially the drone operator, and Caleb was doing the fine-tuned camerawork. In that case I was in VR, because it was the only way I could fly it and know where I was going, and where to bank. “Or you could be holding onto a branch in VR,” he continues, “and you could watch the camera, and then when the camera settles, you put the branch back, so when he pans back you know it’s in the shot — exactly like you would on a [set].” As a further benefit of entering the virtual world, Legato says, “you could see that if you took a step to the right, you might be on a rock, so you wouldn’t necessarily put a camera there — you might go above it or around it. And when you’re [later] operating the shot, you know that if you pan over too far, that’s where the rock is. You have an awareness of your surroundings, and that helps, psychologically, to make you operate the shot a little better and more intuitively, because you’re not a magic camera that’s floating out in space. You are taking into account the physical limitations, if you want them. And if you don’t want them, you can just move the rock out of the way.”

“Sometimes [director] Jon Favreau would sit in VR [at] a little ‘virtual video village,’ and watch the camera department shooting the shots,” adds Magnopus virtual-production supervisor Ben Grossmann. “[This] gave him a more natural interface to suggest changes to the shots, because he could see both the camera feed and the scene at the same time.”](/imager/uploads/76372/Lion-King-10-TLK-Leg-3303_6c0c164bd2b597ee32b68b8b5755bd2e.jpg)

Magic-Carpet Ride

Translating virtual-world camera moves into a real-world production approach.

“We oftentimes had scenes that ran farther than the 25 [square] feet of the OptiTrack space,” says Deschanel. “For some of the musical numbers, we needed to move more than 150 to 200 feet in virtual reality. You could multiply the Steadicam movement to some extent, but not too much. In other words, if 1 foot of a Steadicam move had to become 4 feet, it didn’t feel right.”

To address this, Legato says, the production used “what we call the ‘magic-carpet ride.’” With this technique, the 25'x25' OptiTrack volume was virtually linked to a moving rig, such as a dolly or crane, which — conceptually — transformed the volume’s floor into a platform that sat atop this mobile rigging. Though no such moving platform existed in the real world, in the virtual world the Steadicam operator could perform his work while the “platform” on which he operated moved through the virtual environment.

“The dolly was so smooth you did not feel the multiplication the way you would with the Steadicam,” Deschanel says. “We could get these wonderful mobile moves where it feels like the camera is floating alongside the characters, [with the] Steadicam [moving] around the animals in subtle ways, giving us a feeling of real intimacy with them. Of course, that created the complex problem of, ‘Who does what?’ It became a wonderful dance between the dolly grip [Guy Micheletti (pictured above), for the majority of the production] and our Steadicam operator, Henry Tirl. Henry could say to the dolly grip, ‘You go slower and I’ll take the move up here.’”

“You want the analog interaction,” Legato says. “You want Henry making these artistic choices that feel like a great Steadicam shot.”

Legato further notes that a lateral dolly-move on their real-world stage could also translate to a vertical move in the virtual world, “so it’s as if the dolly is hoisting Henry 25 feet in the air, like a crane — or the volume could be going up a 45-degree diagonal — even though the dolly grip is pushing it on a straight track. You’re moving a 25-foot square anywhere you want to in the world.”

He adds that “it might take four dolly grips to get a dolly up to the speed required to actually track an animal, and then it takes a certain amount of inertia to stop” — a dynamic the filmmakers found challenging to imitate with their 20' of onstage track. The production thus built approximately 150' of real-world dolly track in the Playa Vista facility’s parking lot, and ran a dolly along it, to create the movement “curve” — which was then “imported into the Unity program,” Legato says. When it then came time to shoot the scene, instead of using a live dolly to produce the virtual movement of the volume platform, they simply “played back” the recorded curve, he explains, with the platform “on top of it.” — Andrew Fish and Michael Goldman

Finishing Touches

Company 3 senior finishing artist Steven J. Scott on his detailed shot-to-shot approach.

At the time of this writing, the Lion King filmmakers were diving into their work with Company 3 executive vice president and senior finishing artist Steven J. Scott. Over the years, Scott, an ASC associate, has worked to provide the finishing for some of the industry’s biggest features — but never one quite like The Lion King, which also marks his first collaboration with Deschanel.

“As much as everybody would like everything to come in ‘finished’ [exactly the way] they want, we are doing adjustments [of some type] for every scene,” explains Scott, who works with Autodesk’s Lustre and Flame platforms. “We’re doing some work on continuity, lining things up, [and] we’re doing things to match highlights and isolate certain areas of the characters — all kinds of things. Some of the lions, for instance, might run a tiny bit cyan, so we add some red into them. We’ve been breaking out all the tools and using all the complexities of what we can do. What we are being given is amazing stuff, but given the time frame and enormous complexity, they don’t have the luxury of lining it up and fine-tuning it so everything is perfect. So that’s what we are doing, and we’re also exploring some new looks that were not conceived of before they came to us.

computer-generated world.

“You can do a shot in isolation that can be an absolute masterpiece, and these shots they are creating are just that,” he adds, “but when you string them up one after the other, you realize, ‘Wow, the highlights are really bright in this shot, and then less so in the next shot.’ So we might key the highlights in the second shot and push them to match the previous image better. Or a range of mountains in the background of a shot might be a tiny bit bluer than in the next one, so we will isolate the mountains and line those up a little better.

“For instance, we have a shot on a cliff, and we tilt down to see the character Simba,” Scott continues. “In that shot, we felt the color of the highlights were just a slight bit jaundiced yellow, so we isolated those highlights and took some of that out. But we didn’t want to affect the background, so we were able to pull Simba forward in the shot.

“There’s also a camera move on Simba, and the filmmakers wanted it to feel a bit more organic,” the finishing artist notes. “So we worked with the existing move and put another move on top of it, to give it more of a flowing, smooth, organic quality.

“There is another shot where you’re looking at the sun setting behind the mountains,” Scott says. “We wanted to keep the sun looking beautiful, but bring a little coolness into the mountains in front of it. There are a bunch of hyenas running across the savanna in the shot, kicking up dust, and we thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we could have the sun shine through the dust in a stronger manner, and get an even more vibrant feeling out of it?’ So I used a combination of mattes and keys to isolate just the brightest points of that dust, and when they are going by, it looks even more interactive with the sunset going on behind them. We’re making a lot of those sorts of decisions.”

“It was a real pleasure to finally get to work with Steve,” Deschanel attests. “[He has] a wonderful talent for finding the magic in each scene.” — Michael Goldman