Small Wonder: Marcel the Shell With Shoes On

Director of photography Bianca Cline and stop-motion-unit director of photography Eric Adkins combine live action with animation in charming miniature fantasy.

All images courtesy of A24

Marcel feels pretty good about being a shell. The 1"-tall stop-motion puppet — star of three three-minute shorts written and directed by Dean Fleischer-Camp, voiced in a croaky falsetto by Jenny Slate — was ostensibly a snail shell decked out with miniature shoes and one googly eye. Marcel’s infectious optimism and endearing philosophical worldview attracted nearly 50 million YouTube views and spawned two New York Times bestselling books. Now, the peppy mollusk is the star of A24’s animated feature Marcel the Shell With Shoes On.

To make the film, Fleischer-Camp and Slate joined screenwriter Nick Paley and producer Elizabeth Holm to concoct a 90-minute story that largely retains the setting of Marcel’s world inside a California Craftsman house. Leading the cinematography department were director of photography Bianca Cline, who captured principal photography on location in Los Angeles, and Eric Adkins, who supervised the stop-motion work. Other key collaborators included animation director Kirsten Lapore, postproduction supervisor Jalal Jemison and visual-effects supervisor Zdravko “Zee” Stoitchkov.

“The majority of films like this are often told through a child’s gaze, and that can lead to a look that makes the character feel more magical than realistic,” says Cline, whose cinematography credits include the documentaries Murder Among the Mormons and Belly of the Beast. “We wanted Marcel to feel like a real being, so we needed to create a world that felt very realistic — the most beautiful version of realistic. My main reference came from Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life [AC Aug. ’11].

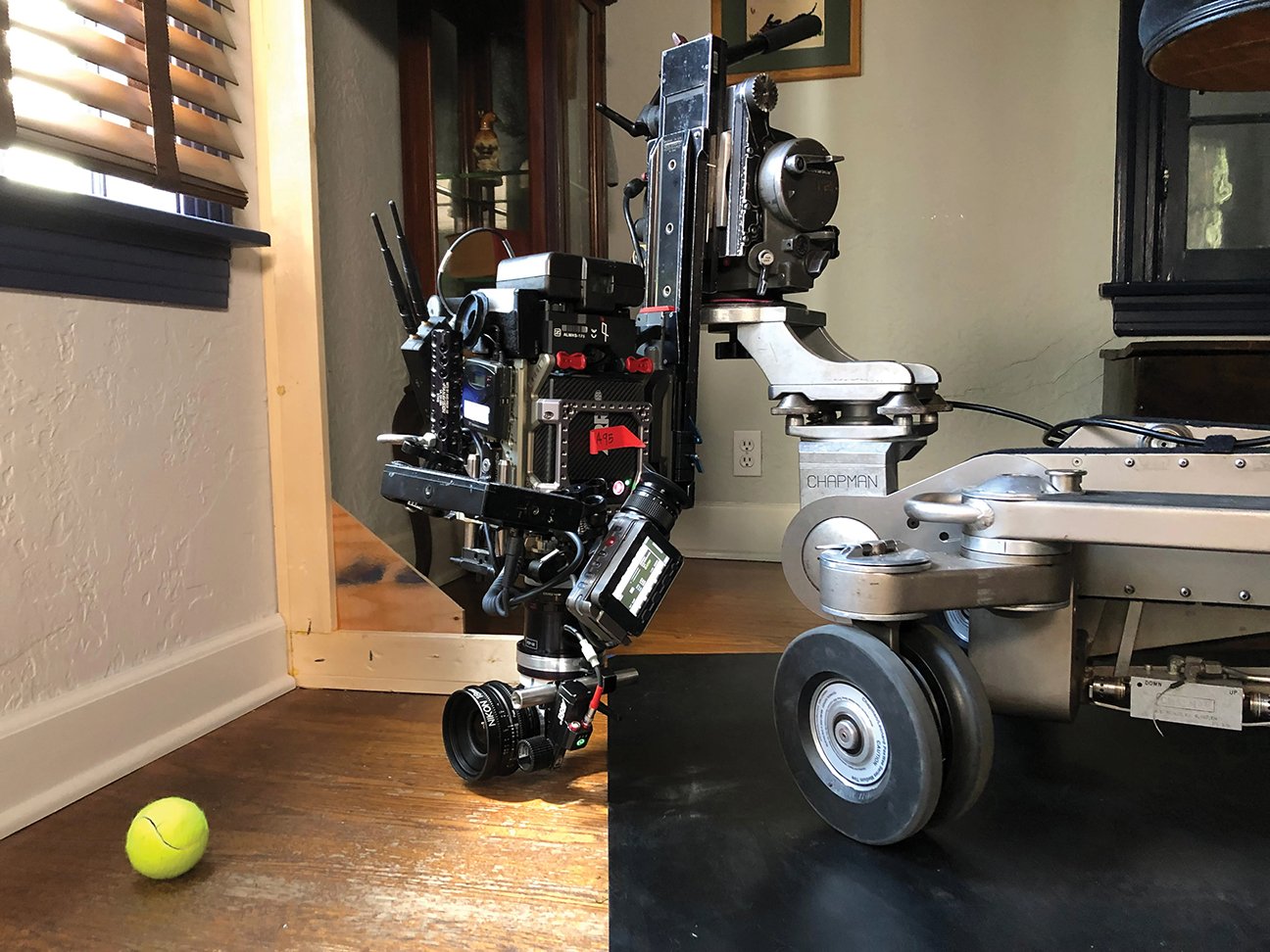

Los Angeles’ Hancock Park neighborhood was a base of operations for preproduction and production. Using animatics of storyboarded scenes with prerecorded dialogue, a small team of puppeteers staged interactions of animated characters on set using static stand-in models. The camera and animation teams then planned interactions to integrate stop-motion animation in a subsequent unit. Adkins, whose credits include Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow [AC Oct. ’04] and The Boxtrolls, notes, “Our principal characters were not created in CG; they were practical objects less than 1-inch tall whose stop-motion animation we fused into on-location plates.

“Bianca established a lyrical documentary style in her cinematography,” he continues. “We placed the characters in scenes through lighting interactivity and surface reactions, with shadows and reflections. We documented and analyzed camera setups, then re-created those with similar beauty, tracking and scaling camera moves in a controlled studio setting. The lighting included many moods and sometimes called for motion control, with variable camera and lighting cues. We had many locked-off shots — 2D-stabilized plates with simple axis movements shot as lock-offs, and then we motion-tracked camera motions back in — and we also had full 3D-tracked and scaled plates with multiple axes of motion control.”

Crafting “Imperfection”

Digital motion tracking allowed the filmmakers to embrace handheld camera techniques, reinforcing the conceit that the film’s human protagonist, a filmmaker named Dean (played by Fleischer-Camp), is capturing Marcel’s conversation for a documentary while renting the house where the amiable shell resides with his grandmother, Nana Connie (voiced by Isabella Rossellini). “We wanted to create the most beautiful version of a documentary that we could,” Cline says. “But we always wanted to make it feel off-the-cuff. Our mantra was to find a shot and then to ‘throw it away’ a little. Once we found the image, we added imperfections, such as unsteadying, or ‘bobbling’ the camera. For instance, if Marcel made Dean laugh while Dean was filming, we’d move the camera for a second or let the focus go in and out. We worked out focus marks and shot a pass with our [stationary] Marcel stand-in. After that, we’d shoot a clean plate, and we’d tell the focus puller to roll through the focus as if they were trying to find focus.”

Working with Chiodo Bros. Productions, the animation unit replicated imperfections in stop-motion photography during a 12-week shoot at Bix Pix in Burbank. “I was always looking for lighting cues to put the character in that space,” says Adkins. “If there was a lightbulb on the ceiling reflecting off a wooden surface, I would take note of how Marcel interacted with that if he cast a shadow and a reflection. And sometimes we faked object shadows. If we had a wooden surface, the VFX artists would pull the glare off that, and I made sure there was a reflection of the shadow of a solid object that Marcel would interact with as he walked across that surface.”

Lighting for Mood

The lighting scheme followed a narrative arc, starting with bright sunlit scenes and progressing to melancholy tones in the second act before finally resolving in a sunset. The interactivity anchored animated characters in their own reality. “We wanted to put things in the frame that you seldom see in a stop-motion world,” says Cline. “Flickering or moving light felt more realistic, more like the real world.”

The live-action and animation teams both made use of DMX systems to control lighting. Cline and gaffer Brice Bradley used DMX with an iPad app as a dimmer board, shooting 24 fps with an Arri Alexa Mini. Adkins and his team used DMX to keyframe lighting cues with motion control, serving 14 stop-motion units employing Canon EOS R cameras with upgraded HD live-view feeds.

Animators aligned puppets to plate photography in digital overlays using DZED Systems’ Dragonframe software. “We called this process ‘frontlight/backlight’ because we didn’t use bluescreen,” Adkins says. “We created an alpha matte to pull keys on white or gray surfaces, in which we would capture a separate exposure in silhouette without the need for color suppression in the beauty exposure. We used DMX lighting controls built into Dragonframe to change lighting per multiple exposure for each frame of animation.”

Housing the majority of Marcel’s universe in one location allowed the live-action unit to take advantage of natural light. “I got to do lighting scouts for the entirety of preproduction,” says Cline. “I’d come in early and notice that one room looked amazing at 7:30 a.m., while another room looked great at 5 p.m. We planned our days around that and lit the scenes to feel naturalistic. We didn’t add unnecessary backlights, but we did want scenes to feel like the sun was coming through windows, so we used a lot of Molepars outside the house to send hard shafts of light inside.”

Cline paired the Alexa Mini with Nikon prime lenses rehoused by David Bibi Cox at Eastern Enterprises. Due to the close-focus work for the small models, the cinematographers had very shallow depth of field at 12" focus distances, even at T8.

On the Move

In one of the film’s most dynamic sequences, Marcel seeks information about missing members of his family by hitching a ride on the dashboard of Dean’s car. “We wanted that sequence to feel slightly different,” Cline says. “We figured Dean was filming Marcel in the house using an Alexa so it would look high-quality, but we thought the driving sequence could be motivated by the aesthetic of GoPros. We filmed all of the car plates with the Marcel stand-in on the dash of the car. We drove the route and let the lighting be whatever it wanted to be. It was very chaotic, with light bouncing off buildings, trees and all sorts of colors.”

Inside the car, GoPros, visible in shot, were affixed to the windshield via suction cups, while an Alexa captured forward views from the back seat. The animation team reconstructed the dashboard with Marcel standing on a map, getting carsick.

“The GoPro was the most volatile of cameras to analyze,” says Adkins. “We used contrasting flicker and blown-out auto exposure, along with mounting our lights on a motion-control arm to mimic the action. We studied the plate photography, matched the shadow motion and duplicated that lighting based on the overlay per frame through Dragonframe. We then added light fluctuations with preprogrammed spotlights going on and off using DMX. while we swept a motion-control arm across laser-cut tree branches for shadows, and we faked a harder shadow of cool sunlight to mimic the car’s quarter-panel as light moved across the dash.”

A Poetic Farewell

Marcel’s celebrity eventually brings a 60 Minutes news team to the house. Sony F5 cameras were used to shoot material “meant to have been filmed by the 60 Minutes crew. We were attempting to mimic the look of their show,” Cline notes.

The sequence allowed the filmmakers to cast interiors in a twilight-like gloom for a touching scene in which Nana succumbs to her illness and, poetically, vanishes into a sunbeam. “Thematically, we knew this film is about loss,” Cline explains. “We also knew a lot of children would likely watch the film, so we didn’t want Nana Connie’s death to be super sad. She’s going away, but we also wanted it to be beautiful because she’s a beautiful person. We knew a 60 Minutes crew would likely black out the windows. We thought maybe there would be a little bit of light sneaking in where Nana was sitting, so we put Molepars outside the window and added a little bit of atmosphere.” Puppeteers walked Nana’s stand-in through the shot for focus, and then Cline filmed a clean plate. The animation team later replicated the interactivity of Connie walking off into the fog by shadowing shafts of light, and then visual effects faded the character away.

The film closes with Marcel visiting the basement laundry room, from which he observes a beautiful sunset. The filmmakers staged the room with a west-facing wall and window, planning their lighting using the Sun Seeker tracking app, and then captured the scene in a slow, rising push-in. “That was probably our most difficult shot,” says Cline. “We did 10 takes pushing across a concrete floor from one end of the house to the other. We had lights just outside the window creating soft [supplemental] light coming through. I had them paint the set white because I wanted a little extra bounce. We knew that had to be the most magical of all the scenes, so we timed it with the real sunset outside the window, coming through the trees.

The animation team placed Marcel on the sill, matching the plate. “We only animated a certain frame range of Marcel in that shot,” Adkins says. “He wasn’t visible until the camera got closer, and the sill gave us a natural occluding edge. The plate had sheer curtains moving in a gentle breeze and natural tree shadows. We re-created that dapple effect with motion-control branches with the appropriate diffusion and color temperature taken from the live action, and then timed those with DMX-incremented light fluctuations.”

Upon seeing the finished film for the first time, Cline found the illusions she had helped to create so convincing that she “started crying three minutes into the movie!” she recalls. “I couldn’t believe how well it all worked together. Marcel felt like a real character, and that was our main goal. We worked hard to make it feel effortless.

1.66:1

Cameras: Arri Alexa Mini, Sony F5, GoPro, Canon EOS R

Lenses: Nikon Nikkor prime (rehoused); Panavision zoom, Primo prime;

Fujifilm/Fujinon XK Cabrio