Many Hands Make Martian Memories in Total Recall

Detailing the process Dream Quest took to create the look of this epic sci-fi action film.

The ad campaign for Total Recall proclaims “They stole his mind — now he wants it back!” The same could be said for visual effects supervisor Eric Brevig, effects director of photography Alex Funke and their dozens of overworked acolytes at Dream Quest. After so many months of designing never-before-seen effects to capture director Paul Verhoeven's epic vision of Mars, Dream Quest's artists must feel as if their minds are no longer their own.

Verhoeven is used to getting the most out of his effects crews by taxing their talents to the max. Nowhere was that attitude more evident than on Total Recall. Brevig had supervised Big Business and Scrooged at Dream Quest, and Captain EO at Disney. Though he has worked at several major effects studios, and in every department at Dream Quest, Brevig is quick to point out that "This is one of the largest projects I have ever supervised."

Alex Funke began his career shooting TV specials with Stephen Burum, ASC then joined designer Charles Eames for 12 years, before beginning his visual effects career at Apogee on the pilot film of Battlestar Galactica. Last year, he supervised the miniature photography for Academy Award-winning The Abyss.

An alien civilization has condensed a lot of air and stored it in the center of the planet Mars, which is now home to a mining colony whose principal import is oxygen. This is the dilemma of Total Recall's storyline. Naturally, the man who sells the miners their air, the villainous Cohaagen, wants to keep the inhabitants ignorant of the idea that there is an entire artificial atmosphere waiting to be unleashed. Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) knows how to liberate the atmosphere but the villains have erased his memory. His quest is to regain his lost memories, free Mars of Cohaagen's totalitarian control, then turn the planet into a paradise where one can actually walk outside and breathe.

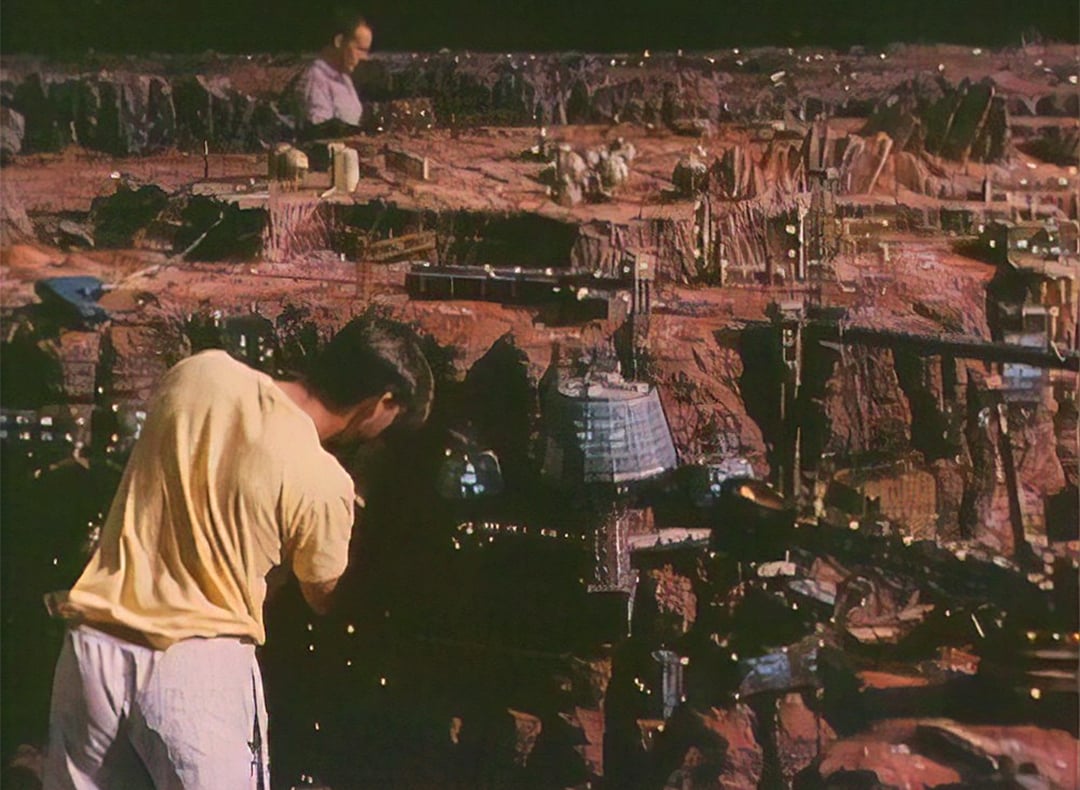

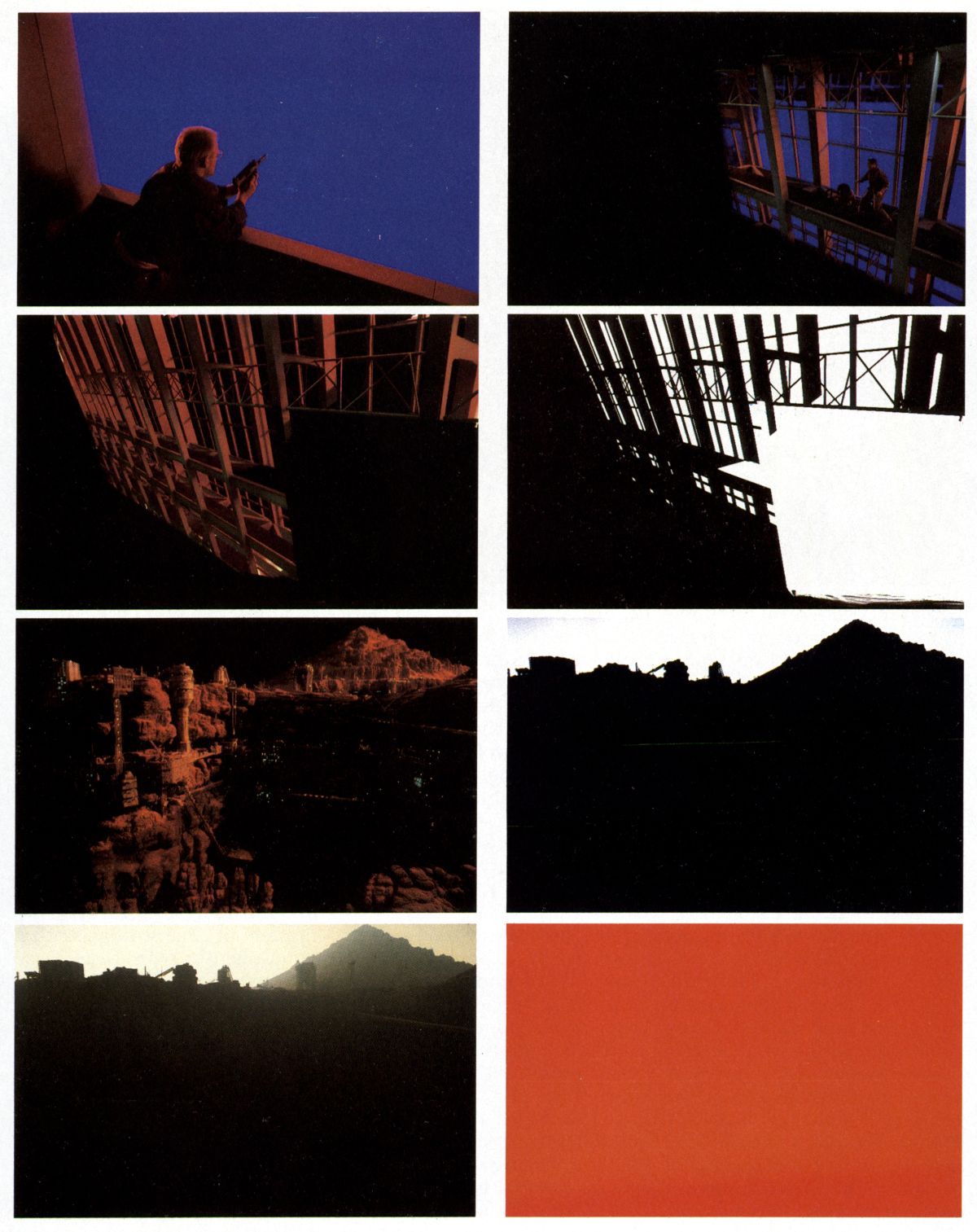

Since Total Recall is almost entirely set on Mars, the film had to appear as if made on location, which meant limited exterior photography for a film with any number of exterior sequences. For most exterior shots, Brevig and Funke had to create a believable Martian landscape, including the red rocks and reddish sky of the god of war's domain. Though a basic Martian landscape set was built full-scale at Churubusco Studios in Mexico City, where Total Recall was shot, it wasn't nearly large enough for the vast exteriors Verhoeven hoped to capture on film. "The Mars rock set was about 15' tall, 100' wide and almost 60' deep, but it really amounted to little more than a patch with this little ridge of red rock," Brevig says. "Every time you see someone walking on the surface of Mars, it is always this set doing triple duty aided by the miniatures built for us by Stetson Visual Services and our matte painting skies."

To create the illusion that Quaid and his companion are walking alongside a vast Martian canyon, the actors were filmed on the all-purpose Mars set, which was later amplified considerably in optical. "There's a little bit of matte painting to hide the fact that the set wasn't quite big enough, then there's the strip they're actually walking on, and everything else is a forced perspective miniature," Funke recalls. "The blending of miniature, live action and matte painting required a lot of balancing to determine what the contrast would be and what color the landscape would be. We quickly discovered that it was the fine detailing on the miniatures, like the size of the sand grains we used, which made the landscape convincing, and which was integrally related to the photographic aspect.

"The dressing of the model affects the contrast, because the size of the shadows on the model are directly related to whether we used sand grains or pebbles in our miniatures, which in turn affected how much black was mixed into the scene. We did a tremendous amount of fooling around until we finally worked out a system to determine exactly what the scale had to be in order to get a certain color and contrast to the landscape.

"As much as possible, we wanted to re-use the miniature parts that we'd already had built, like canyon walls and mountains, so we ended up redressing everything with existing pieces, because it would've been impossibly expensive otherwise," Funke adds. "Once we finished with one set, we had to have a plan afoot for picking up all the miniature parts, moving them around and reconstructing something else. Plus, we were workng Stages 4 and 5 here simultaneously, shooting essentially opposing views. In other words, if Stage 5 was shooting the view from Cohaagen's office looking over towards the Mars Hilton, Stage 4 was shooting the views from the Hilton Hotel looling back towards Cohaagen's office."

To avoid static backgrounds in the many miniature landscapes, Funke relates: "We made sure we always had a lot of stuff going on for that reason. All the backgrounds we shot had lots of motion: trains, machines, cars driving along the roads and cranes scooping up soil. Some of the motion in the distance is almost subliminal, but those small details kept these shots from looking static, and instead gave the feeling of looking at a real landscape."

The trickiest aspect of the dozens of large Martian landscape shots was deciding how to portray an alien environment trapped in a vacuum. Brevig and his team of effects artists found they couldn't use the conventional methods of shooting landscapes in a smoky atmosphere to diffuse the background with an atmospheric haze, or aerial perspective. "We had to keep our landscapes sharp to the horizon," Funke fumes. "At the same time, we had to have some gradation from foreground to background to sell the scale. Our miniature sets were built in forced perspective to represent landscapes that reach to infinity, so it was very hard to hold them in focus and have the resolution work properly; the images ended up too sharp. We therefore adopted a technique where, if the scene was taking place in sunlight, we shot our initial motion control passes in clean air. After, when we did our fill light pass, we shot the models in a very faint smoky atmosphere. In many cases, these scenes involved tracking motion control moves done on-set in Mexico, where the camera's following Cohaagen around his office. This meant we had to match move the background into the shot using motion control, so we were not only tracking the landscapes, we were tracking the sky matte paintings by Bob Scifo."

Adding a synthetic sky to a miniature shot is one of the toughest assignments you can give a special effects expert. It's so daunting a task that only one film comes to mind where synthetic skies were used extensively: Damnation Alley, one of the most disastrous effects films of all time, and an acknowledged classic of sky problems. "Any time you try to matte a miniature foreground into any kind of sky, the problem is that the edge where the two come together is too sharp," Funke sighs. "Almost every shot in this film had to have a sky matted in, and each one had its own special characteristics. Eric devised a brilliant solution: we shot two mattes. First, a normal matte of the edge of the horizon, which was a lighted white surface adjoining the dark horizon of the landscape — and a matte in smoke, which made the white matte flash down over the edge where the landscape and sky meet, so it grades down very gently and softens the hard edge. When we put the sky in, we used both mattes together, so the sky exposure leaks very slightly down below the horizon to create a faint fuzzing of the edge, and it looks very beautiful."

"During the live-action production we had many discussions with the director and the cinematographer [Jost Vacano, ASC]," Brevig says, "but they didn't really want to yield to the idea that we should have a bit of atmosphere, even though Mars itself actually has dust clouds and winds. I came up with the idea of using a smoky matte and a clean air matte together, which gave us infinite variability to the amount of atmospheric perspective you see.

"On Earth," Brevig continues, "when you look to the horizon, the sky color fills in the atmospheric shadow area proportional to the distance. By shooting very dense smoky mattes backlit, we were able to create a photographic element that allowed us to percentage in the matte painting sky exactly proportional to the distance. It allowed us to adjust this percentage from shot to shot, so if a sequence looked a little too clear, we could fix it."

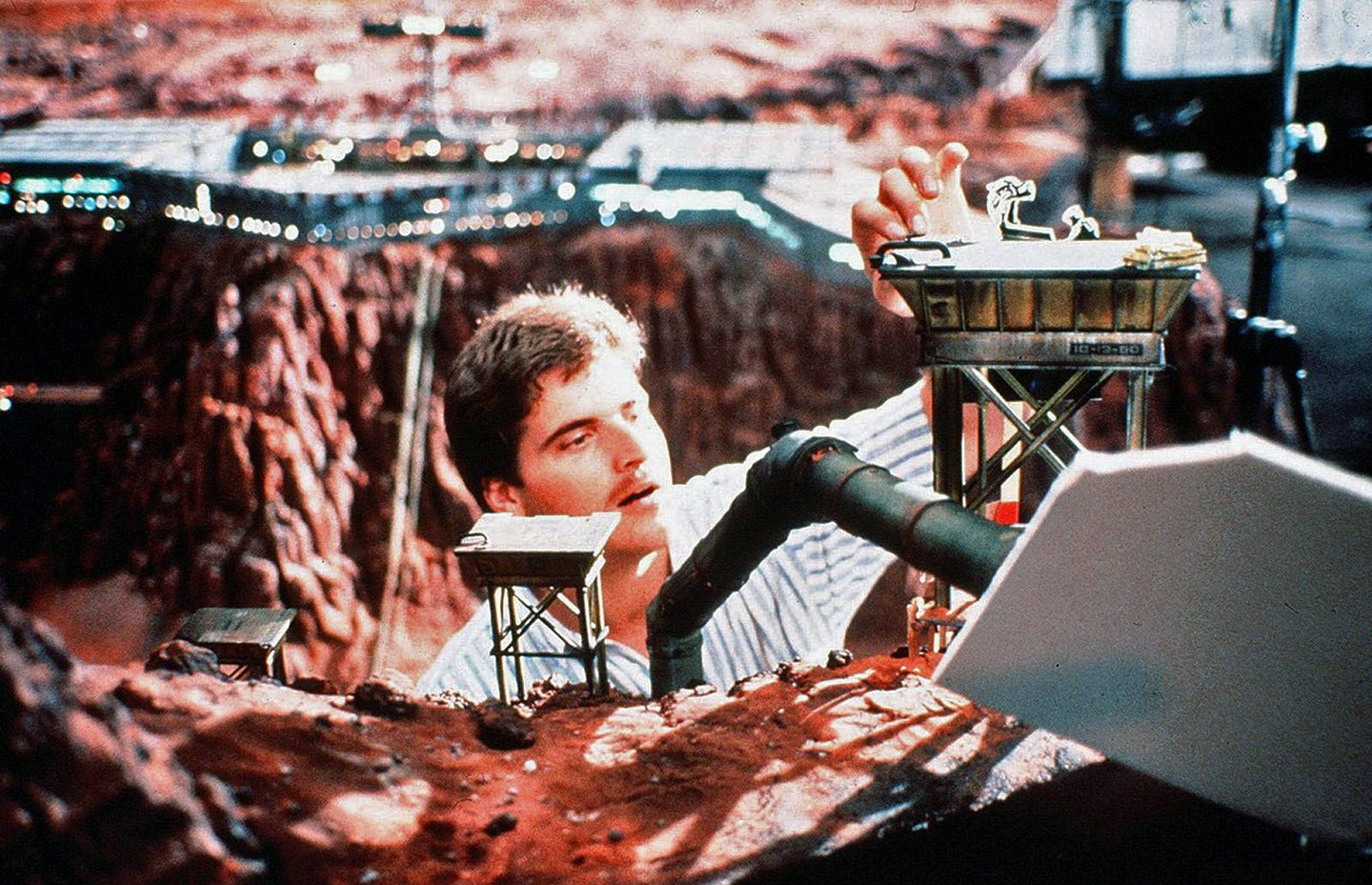

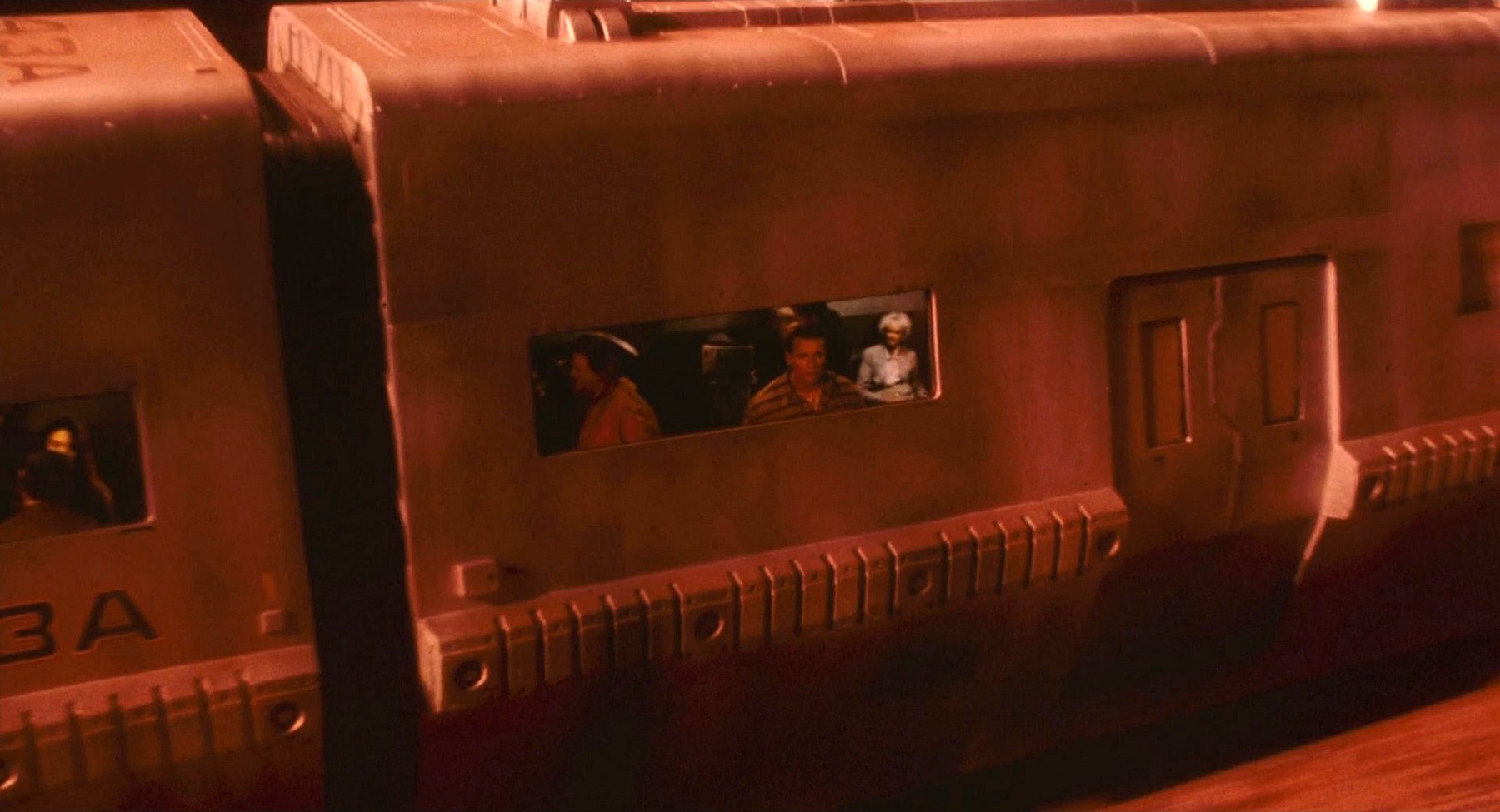

Quaid's arrival at the Mars spaceport and subsequent train ride into the Martian city is one of the most spectacular effects highlights in a spectacular show. The sequence actually encompasses two elaborate effects shots. The first begins as a motion-control move following Quaid inside the train with interactive lighting from the miniature scenery racing by outside the window.

"The interesting problem of this shot was to build the miniature so that it had the correct feeling of speed and the correct depth,' Brevig recalls. "We wanted to create the sense of the foreground landscape going by very quickly while the huge mountain in the distance barely moves at all. To do that with a single miniature would've required an enormous, building-sized set, so we shot this by gradually changing the scales of the miniature. To generate the proper sense of speed and depth, this shot actually had four different layers, and they're all moving at different rates. For example, the huge mountain in the far distance is in fact much closer to camera than it appears to be — it was shot in the same plane as the foreground rocks right next to camera.

"Essentially, we did a kind of reverse forced perspective — instead of starting big and getting small, we started small and got bigger, and moved the models further away to create the sense of speed and to keep the sizes correct. We also motion controlled the foreground rocks, so the camera's not only moving, the rocks are also moving to increase the apparent speed. Similarly, the posts and railway markers just outside the train's windows have to appear to move faster than anything else, but it would've been impractical to put them close enough to actually let the camera create the movement, so we physically moved them so they'd go by in a blur. They're on a tiny track in front of the camera, parked 1/2" out of frame, and they're motion control programmed to zip by and then stop outside of camera range. The whole post movement rig is actually moving with the camera relative to the background."

The reverse angle begins on a closeup of the window outside the train with Schwarzenegger rear projected inside. First, the camera pulls back to reveal the train going inside a tunnel. Next, it flies over the tunnel and over a ridge to reveal the first big view of the Martian canyon mining city, which is an entirely different scale model than the train-into-the-tunnel miniature. "A shot blending two different scale models in a seamless move has been done before and you've seen people projected into models before," Brevig smiles, "but we tried to take this to the extreme by designing a shot that appears to be one continuous shot from start to finish. Then, just when we thought we could barely pull it off they said, 'Add a couple seconds on the head of this shot!"'

Funke had already planned the 60' camera move, which involved two sets of 60' motion control track — one for the camera, one for the train so they could track together. "After we said, 'Sixty feet is all you get!' then Paul said we had to find a way to hold on the train at the beginning of the shot, look in the window and see Arnold," Funke remembers incredulously. "So at the head of the shot, while we're holding on the window, nothing is moving except the poles in front of the camera and a projection of the rocks until the camera starts to hover away from the train and then we're moving. To create the illusion that Arnold is actually on our miniature Martian train, we used two of the mini-projectors we built for The Abyss — one plays a clip of Arnold talking to a miner in one window, the other shows some people in the next car standing and reading the paper. The reflection of the landscape in the glass is a matted element, and the yellow posts that go zipping by were actually in front of the camera. After we lift up over the tunnel, we're in a full matted view of Mars. There's actually a matte split as we go over one set and come into the other. The new set is in a much smaller scale — 1/126 scale — while the previous set was 1/12 scale. In other words, a man would be 6" tall in the first set, and in the other set, 1/8" tall. Everything about this shot was tough — we shot the two sets two months apart, and had to scale down our match move appropriately so it would appear to be one continuous move."

When Quaid arrives at the Mars Hilton, his entrance is shot using a wide-angle lens and a motion control pan, even though the Martian landscape is clearly visible out the giant windows with real glass and a gigantic bluescreen rig outside.

Everything was done very throwaway," Brevig observes, "like the shot of Arnold walking through the Hilton. Paul didn't want the camera to sit there and show off effects shots. If you look outside and happen to see the entire canyon and the mountain and the Mars sky, that's just what happens to be there. Of course, we feel a little differently..."

Quaid's walk through the Hilton lobby required Brevig and Funke to match their motion-control camera lens to create the same lens distortion on their miniature landscape as appeared in the original photography. "In some cases, you can take the liberty of using a different focal length for the miniature background if you want it to appear bigger or smaller," Brevig explains, "but because of the distortion that comes from a lens this wide, unless we matched it exactly in addition to everything else — the perspective, the shearing, the nodal camera position — you would see that the grid formed by the windows would distort in one pattern, while the mountain outside would not, which would give away the trick."

This shot also exemplifies one of the main difficulties Brevig and company had to contend with in the original photography, which remained a difficulty through the optical compositing — lighting vast areas for bluescreen. "We worked in Mexico City for six months, doing some of the most elaborate bluescreen rigging of any show that's been done, between the size and number of screens," Brevig notes proudly. "We would take giant bluescreens to the set as opposed to doing what is traditionally done, which is to stick the screen on stage and then build the set in front of it. By doing it this way, we were able to leapfrog from set to set to set, and always have bluescreens available which were usually rigged the day before we'd shoot and struck the day following the shoot — and each was a custom rig."

The Hilton lobby was a very large set to light, especially since everything out the huge picture windows was blue screen. "For that reason, we couldn't have lights shining through the windows," Brevig shudders, "so the room had to be lit from way off to the side. Similarly, we had to light the bluescreen, so we used a frontlit blue screen 40' x 60' just to get it far enough away from the windows so it didn't flag all the light coming in from the sides. Since it was frontlit, we were constantly trying to hide forty 10' x 5' panels completely ringing the window all the way up the 50 foot height of the stage. We had to light the cloth but we couldn't let the blue reflection spill into the room, and we needed to get the effect of sunlight streaming in but we couldn't because of the bluescreen. It was a very complex and self-contradictory set-up. The optical department here had to work that much harder."

Funke nods his agreement: "For this sequence and some of the Cohaagen shots, we actually optically synthesized red reflections out of the blue reflections in the sets. We wanted our floors to look real, so they had to be shiny like real floors, but if they're shiny, it's almost impossible to keep the light of the bluescreen off them. In the finished shots, you can see the red reflections of the landscape on the windows and the on the floor, but in reality, there was a bluescreen out there so we actually had blue reflections on-set, blue spill on the desk and so forth. Were we not to do this synthesis of red reflections out of the blue ones, all these reflections would go dead black as if they were unlit in the optical stage when we took out the blue. We tried it that way at first, but there was something unrealistic about it, so by using a very complicated series of rotoscoping mattes to separate the areas that had reflections on them, we could false-color them red, giving us the reflection of what should be out there in a way we could never achieve in reality. It's something you don't see but which has to be there to sell the illusion."

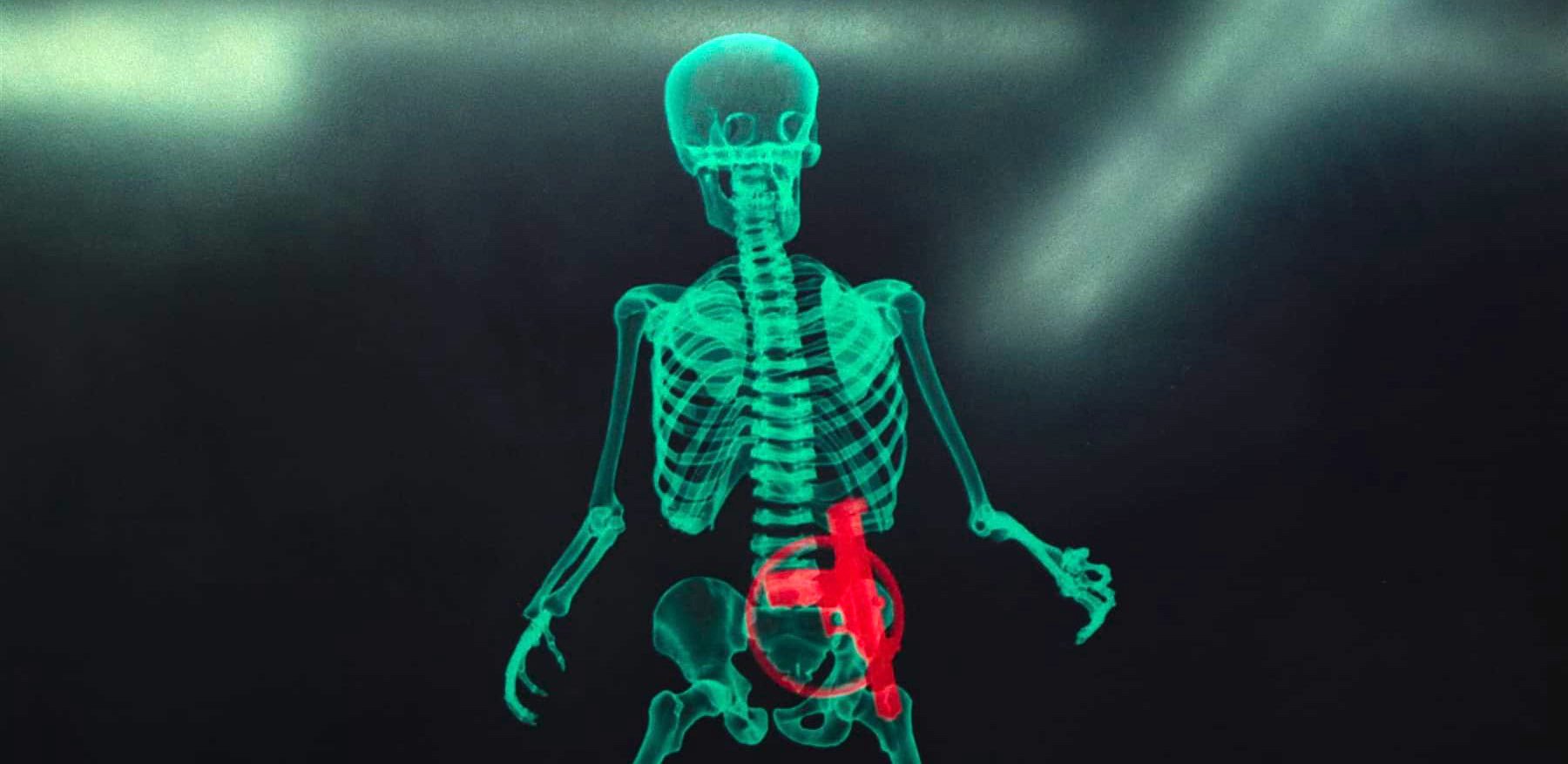

One of the most exciting illusions is the “skeleton” security screen — an X-ray detection device that projects a person's skeleton onto a black glass shield as he walks along a 30-foot ramp. The half dozen aqua blue skeletons seen walking across the charcoal screen were created via computer generated imagery (CGI) by Metrolight, a computer graphics company, in association with Dream Quest.

Quaid attempts to get through the skeleton security screen carrying a weapon, with Cohaagen's goons in hot pursuit. The alarm immediately sounds as red rings radiate from the red gun at Quaid's skeleton's waist. Realizing if he runs out the far side, he'll be caught by the guards manning the security checkpoint, while if he heads back the way he came, the goons are waiting to shoot him, Quaid takes the only option available to a character played by Arnold Schwarzenegger — he leaps through the plexiglass wall of the security screen. Technically, much of the effects work was the same as in the standard operating skeleton screen sequence, until Quaid leaps through the screen. As his skeleton begins to smash the glass, it breaks up as Quaid's body follows through the screen. "It was fairly tricky for the computer graphics people," Brevig says. "Of course we had a stuntman coming through the glass from behind, but when we recorded the skeleton's motion there's no way he could recreate the stuntman's motion perfectly."

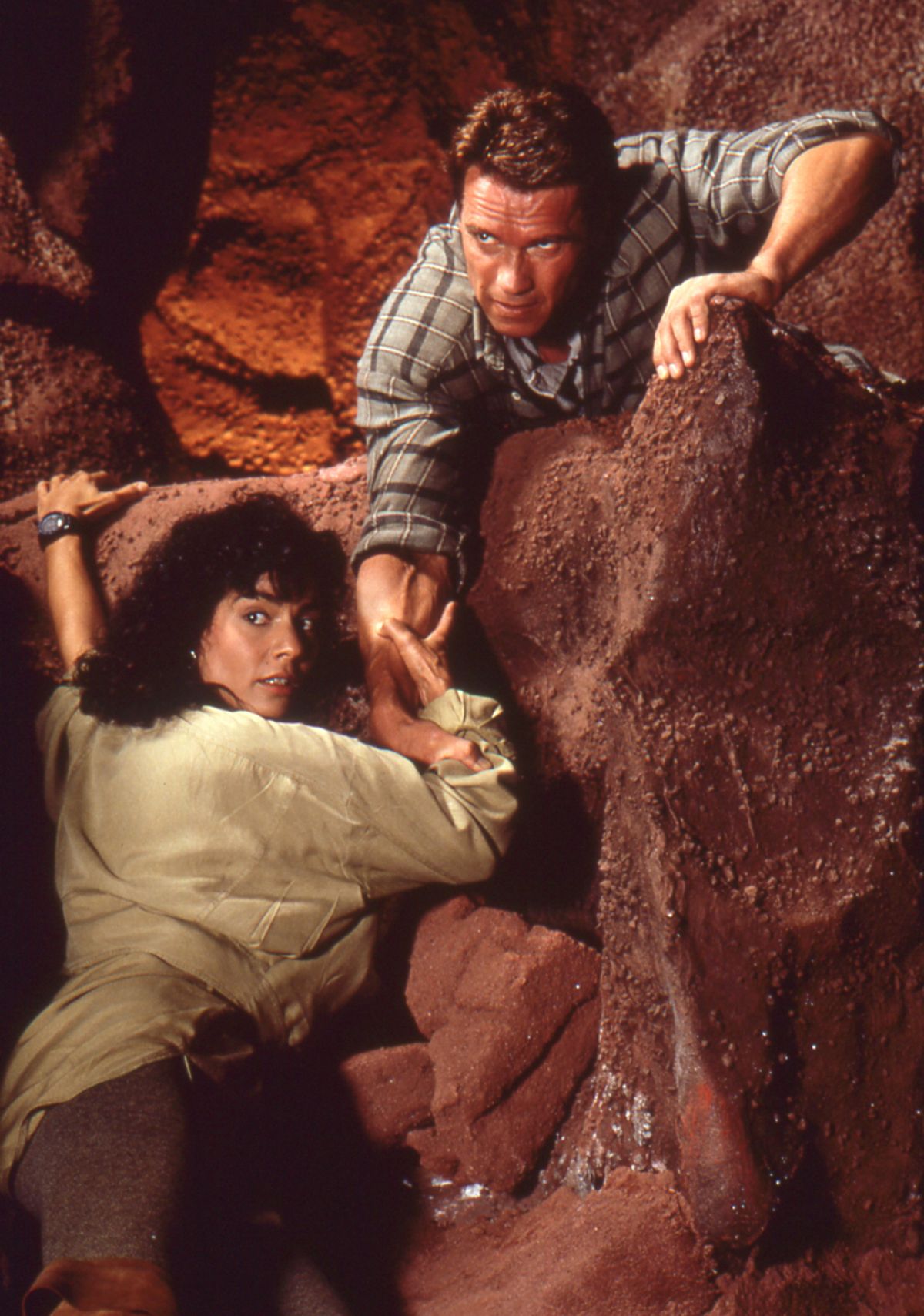

The chase continues as two Cohaagen goons follow Quaid and his girlfriend Melina into the Hilton, where the heroes leap off a balcony onto a grid in front of the hotel's giant picture windows looking out on Mars. Quaid and Melina climb down the grid, as their pursuers watch, afraid to follow and afraid to fire at them because it would blow a hole in the glass and all the air would shoot out. In reality, all that exists full scale are the two sections of grid in the foreground and the balcony set," Brevig said, "but the balcony and grid aren't even in the same place! Because of the incredible depth of field we would have needed to shoot these both at the same time, we shot them as layered elements.

The bad guys were shot against one bluescreen on the balcony, while the section of grid with Quaid and Melina climbing on it was shot on another stage against bluescreen. Another shot in this sequence was known as the 'ladder of death,' because the motion-control rig, including its very heavy motion-control tracks, was mounted at almost a true vertical — in fact, we had to counterweight the camera rig to keep the dolly from lifting off the track! We ran cables up to an encoder atop the 'ladder of death' that went to the counterweight — which was a giant trash can full of sand manned by several grips who then lowered the unmanned camera while the pan and tilt were operated remote a la hothead. That move was recorded and scaled down for the background shot."

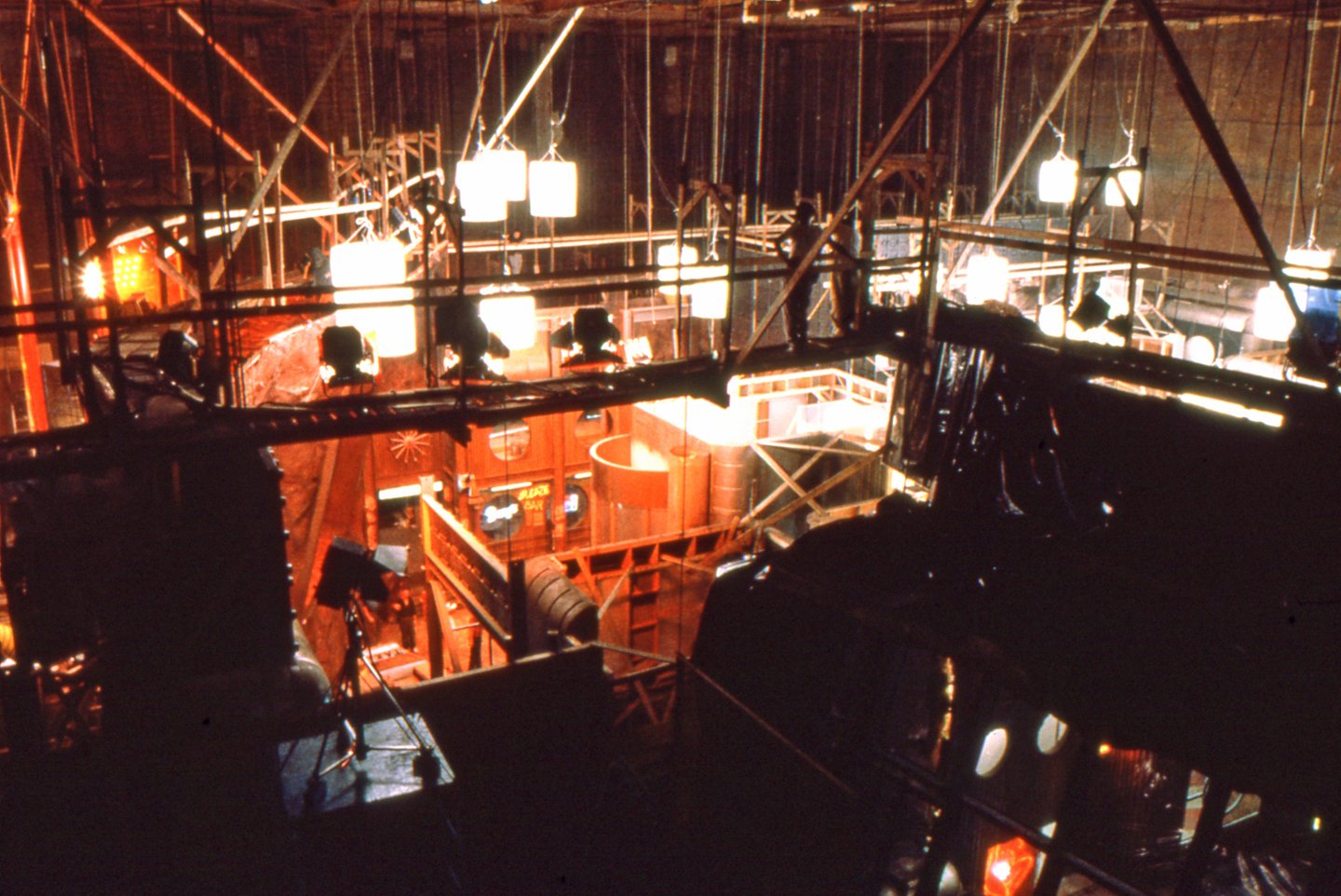

The true power of the ancient Martians and the key to Mars' salvation and Quaid's sanity is revealed to him in the awe-inspiring mind-probe sequence, one of the most elaborate miniature effects ever put on film. The rebel leader, Kuato, a mutant psychic, leads Arnold back through memories that had been erased from his conscious mind to remember things he did in the past that will tell them how to turn on these machines. The mind probe takes Quaid sailing through the alien reactor miles below Mars' surface, past hanging column-like structures which turn out to be the mysterious alien mechanisms designed to release the trapped atmosphere. The alien reactor miniature is one of the largest and most complex miniature sets ever constructed, and had to be built on its side because that was the only way it would fit on Dream Quest's effects stage. Although the mind-probe sequence appears to be a single shot, it actually has several cuts in it to other miniature environments, many of which are covered by the very fast moves the camera makes from one spot in the mechanism to another as Quaid is led through the machinery one stage at a time.

"This is a rather involved and complex sequence," Funke says with uncharacteristic understatement. "Although virtually all our other work in this film was shot on 8-perf VistaVision stock, this was done on 4-perf just because we needed to use a small camera for clearance in this set, which was enormous, but tiny. Mike Bigelow designed the camera move and shot it. Once we fly past the corridor of alien mechanisms, the camera then drops down into a canyon spanned by a bridge, where we see the bad guys taking pictures with their flash guns. The actors were rear projected into the bridge miniature, which was very tiny, only 1 3/8" wide, while the towers holding the bridge are 6" on a side.

"As we continue into the chasm," Funke adds, "we go down into an excavation and then we're looking up underneath alien mechanisms. The rods we see within them will later become red hot, melting the alien ice that's been there for a million years, which is the frozen atmosphere. Now we lunge from the mechanism back up to the underside of the same bridge on which we saw the bad guys. It's like a mind-jump, and at this point, we change to a larger bridge model so that when we come over the bridge, it can be blended with a full scale live action shot done in Mexico. We needed the larger bridge because we could never get close enough to the miniature bridge to make the cut to the live-action bridge.

The model, replete with chasm, bridge and vast alien mechanisms, was 24' high and 65' from front to back; the columns were 8' long. "The whole thing looked like a big pin cushion with the columns sticking out," Funke laughs. "We tracked along the floor using an extremely long cantilevered arm with a custom built Mitchell camera, from which we stripped every possible thing. We had to create the absolute minimum 4-perf camera package that could be built on the end of an extremely tiny pan, tilt and roll head, because as this thing went through this model, there'd be less than a 1/4" clearance between the camera and the columns. It was like threading a needle."

Quaid and Melina are eventually able to turn on the reactor and liberate the stored atmosphere, "That's the whole payoff of the film," Funke beams. "It's a wonderfully climactic scene where the reactor turns on and these gigantic reactor rods come down, bore into the ice and steam blows up and stuff flies into the air — done using a whole series of miniatures in different scales. We had essentially three scales of miniatures in this sequence: 1 /96,1/24 and 1/8 scale.

"We had a problem with the rods — they had to appear to be glowing red hot — but they were only 3" in diameter in the 1/24 scale miniature, so it wasn't practical to put lights in them because we couldn't control the heat and still get them as bright as we needed. Since there was no practical way of lighting them internally, we wrapped Scotchlight around them and the scenic artists at Stetson Visual Services painted a corrosion texture on them in black and green, which held the light out beautifully. Then Bigelow, who also shot these scenes, put a 50-50 beam splitter in front of the lens, and we projected orange light on it using a modified xenon slide projector, so it was extremely bright.

"We had all the light we could possibly use, we had a mechanism inside the rods that caused them to descend, and we actually faded up the light as the rods slid down out of their housing, then added a little double-exposed enhancement in optical to bring the lights up a little quicker. The projector was built by Optical Radiation Corporation, so it had a mechanical dowser which we motion controlled. Over that, Mike added a camera fade because the dowser didn't have quite the resolution required, so the camera faded in at the same time the mechanical dowser was opened. We also had conventional lights shining on the ice fading up at the same time, to create the look of interactive light shining from the rods onto the ice, since Scotchlight doesn't actually produce light, it only reflects it back to camera."

For subsequent scenes wherein the atmosphere was released like a giant volcanic eruption, Funke supervised many more high-speed shots. "We did a lot of stuff with the camera running at high speeds where events had to be synchronous," he says. "At the back of the set, steam would start to blow and then there would be an explosion and it would come forward - it looked very dramatic and ponderous on film, but in reality it's happening insanely fast because the camera's shooting so rapidly and everything has to appear synchronized on the screen. It's a case where all these things have to fire in unison, and there are dozens of people tripping electrical valves and opening things and posing fire extinguishers underneath the miniature set while someone with a megaphone calls the cadence to get it all in sync. It's hard to reset and we do many, many takes and hope we learned something from the previous takes."

One of the last shots of the film, in which the rebel forces and others emerge from buildings and caves dotting a vast Martian miniature landscape, was a crazy quilt of front- and rear-projected elements. "We start close in on people in a cave, and do a massive pullback to reveal a giant long shot of Mars," Funke explains. "In doing that, we see not only the heroes, but lots of people in windows and standing on the roof of a building and on the ground. There are also people walking around on top of a hill, which was a separate matted-in element. One of the elements was rear-projected into the set, and everything else is front projected on pieces of Strathmore paper. When we were all done, we had seventeen elements to the shot, and it took 28 hours to shoot because of all the color-separation passes on each element.

"The more elaborate, high-tech and state-of-the-art your equipment," Brevig points out, "the more you'll get sunk by something as simple as a three-color separation that doesn't register! It's sort of like student-film problem solving even though it's a giant feature. No matter how high falutin' the techniques we come up with are, and some of them are scary in their complexity, a shot like the pullback with all the people is still solved using technology that's been around since 1920! You're constantly being humbled, you can't take anything for granted. You can have the nicest shot in the world, but if you can't get the three-color separations to register over the people in the window, it doesn't matter how nice your camera move is. There's a real feeling of triumphing against the odds when we pull off shots as complex as these."

You'll find our complete story on the film's cinematography by Jost Vacano, ASC here. And on the groundbreaking "X-ray" effects sequence here.