Total Recall: X-Ray Effect Secures Illusion

CGI animation director Tim McGovern details creating one of this sci-fi adventure’s most innovative scenes.

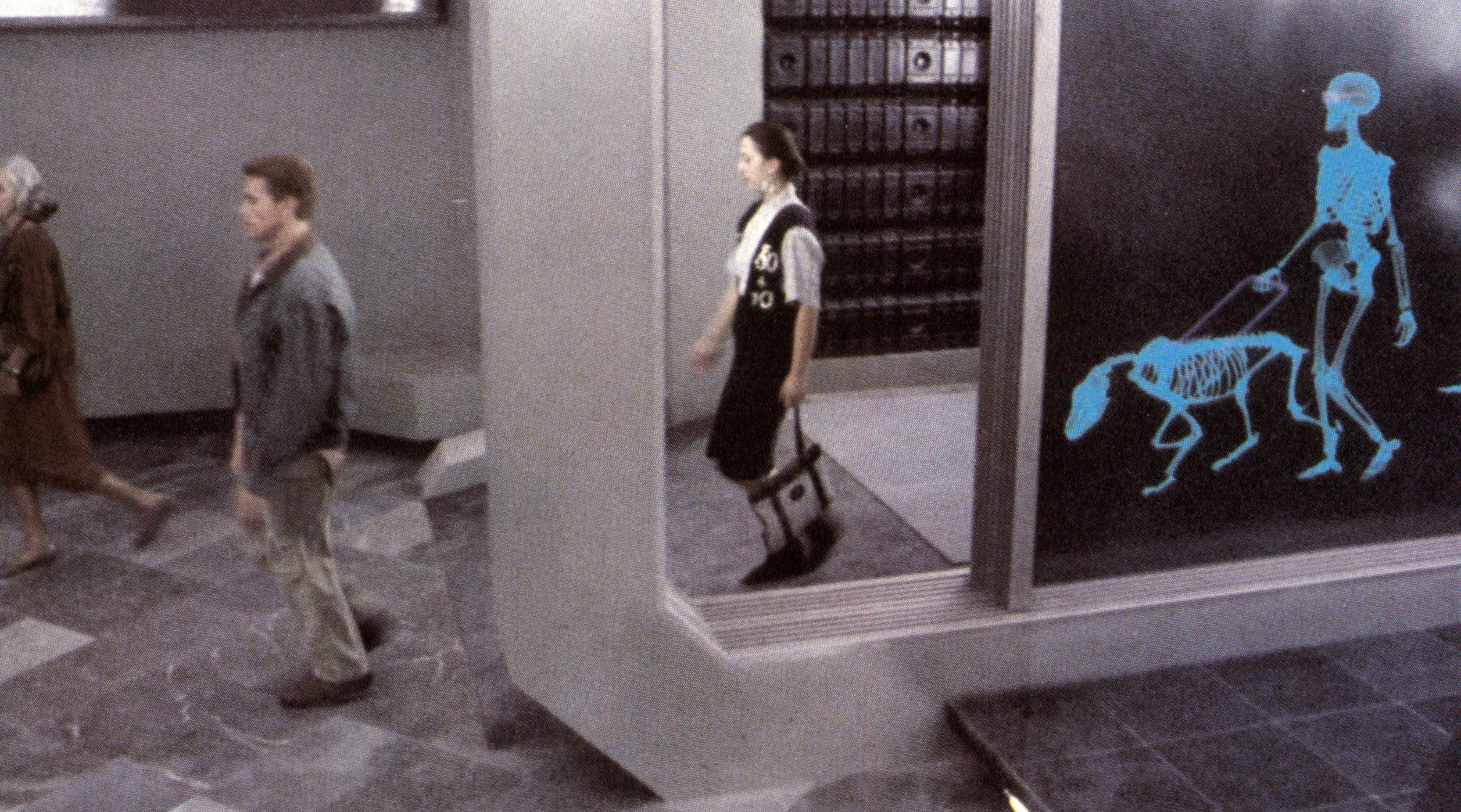

In director Paul Verhoeven's vision of the not-too-distant future, things on Earth are so bad that a ride on the subway requires a full body scan with an X-ray. Verhoeven and company employed the talents of Los Angeles' Metrolight to bring to the screen his slightly sardonic vision of just what this X-ray might reveal in the 1991 summer success, Total Recall.

The two sequences were outwardly very simple. People on their way to catch the underground trains walked through a giant X-ray machine. The length of the machine was approximately 20 feet and one entire wall acted as a screen. Guards sit in front of this wall and watch the commuters, looking for tell-tale signs of weapons. From the time the people enter the machine until they exit they appear as electric blue skeletal images.

The first sequence set up the procedure as an everyday occurrence. The second is an action sequence with Arnold Schwarzenegger running from the bad guys. He runs into the machine and realizes that he has set off the alarms because he is carrying a gun. He looks back where he came from and he sees his pursuers. In front of him are armed guards. So he chooses to jump through the glass panel to escape.

As CGI (computer-generated imagery) animation director Tim McGovern explained it, Verhoeven was taken with the simple graphic look of computer-generated animation. However, even a no-frills approach required three months of work and lots of research and development. Once Metrolight had the green light for the project and before they started receiving dailies from Mexico, where the principal photography was done, an entire human skeleton had to be digitized. Before the digitized skeleton could be animated in any way, McGovern and his team had to collect a lot of information. They had several sources. First, there was the principal photography footage itself. Second, there was some footage of the actors taken from the reverse side of the simulated X-ray screen on the set in Mexico — although that coverage was not as extensive as Metrolight would have wished. Then, there was the reference footage collected by Metrolight's own photographic team.

The method McGovern and his crew used to collect their data was unique and not without problems. McGovern reported that he was never really sure that he would be able to take a crew to Mexico. Ideally, of course, he and his photographic team should have been on the set the day principal photography was done. Instead, when he did get a crew to Mexico, he discovered the set had already been dismantled and the original group of extras dispersed. The set had to be rebuilt and new actors were called in to re-create as closely as possible the actions of their predecessors.

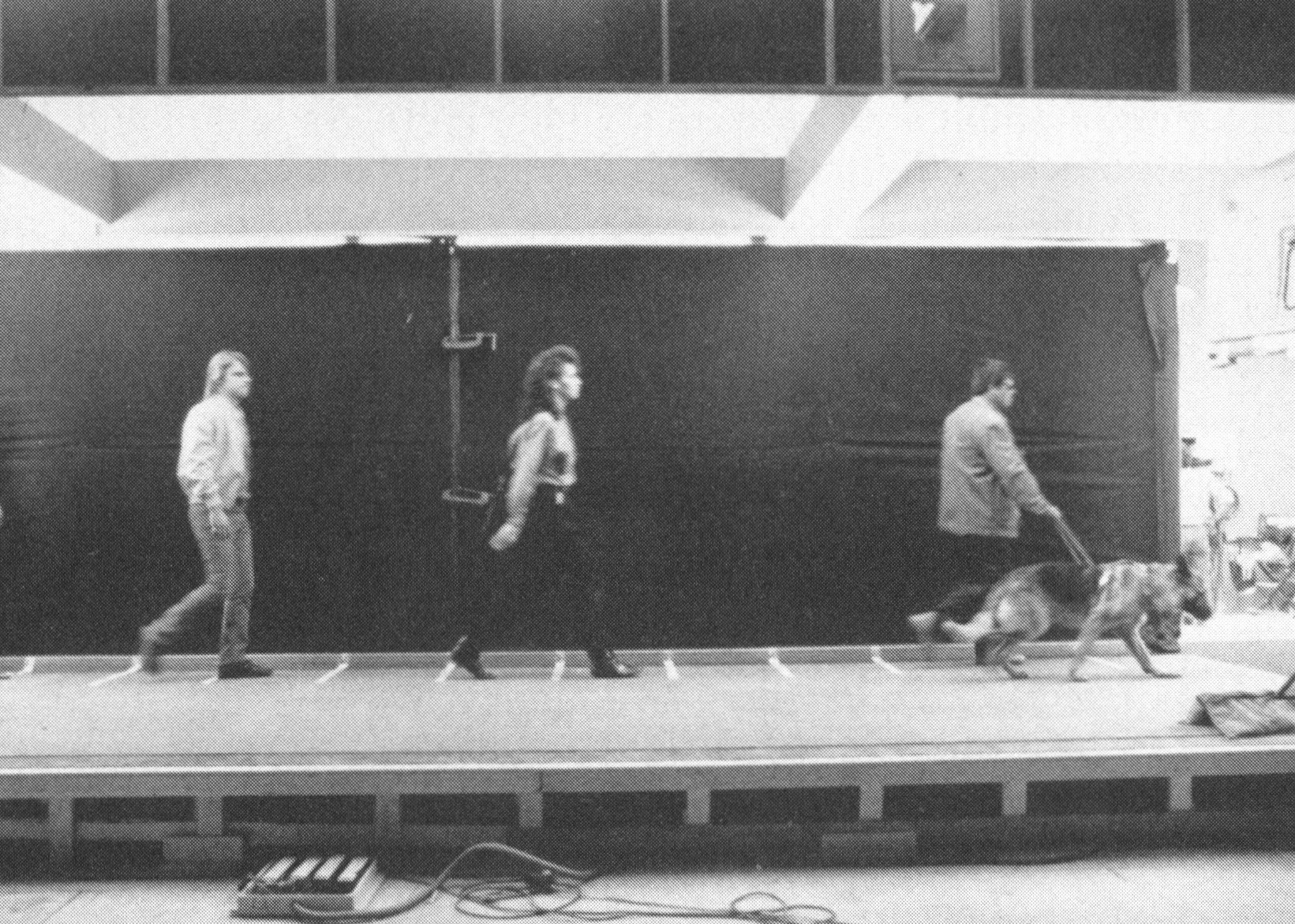

the kind of

information

gathering footage

McGovern and

crew collected in

Mexico.

Each extra's actions as he walked up the ramp and through the machine were recorded separately by six cameras. Each actor was dressed in black and adorned with ping pong balls. Actually, the balls were covered in front projection material and attached to the body at all the major joints and other points that would aid in monitoring movement for later animation. "Mounted over each of the six cameras was a light,” explained McGovern.“No matter where the actor was in the scene, the ping pong balls reflected back to the individual cameras perfectly. The camera was always on axis with the light. What that gave us was a series of points of light on the film. The balls were positioned at each of the points we thought we'd have to track in order to get reasonable information. We used three on their heads, and that turned out to be overkill. But one on the top of the head wouldn't have been enough because if the actor turned we wouldn't have gotten any location information from that one ball."

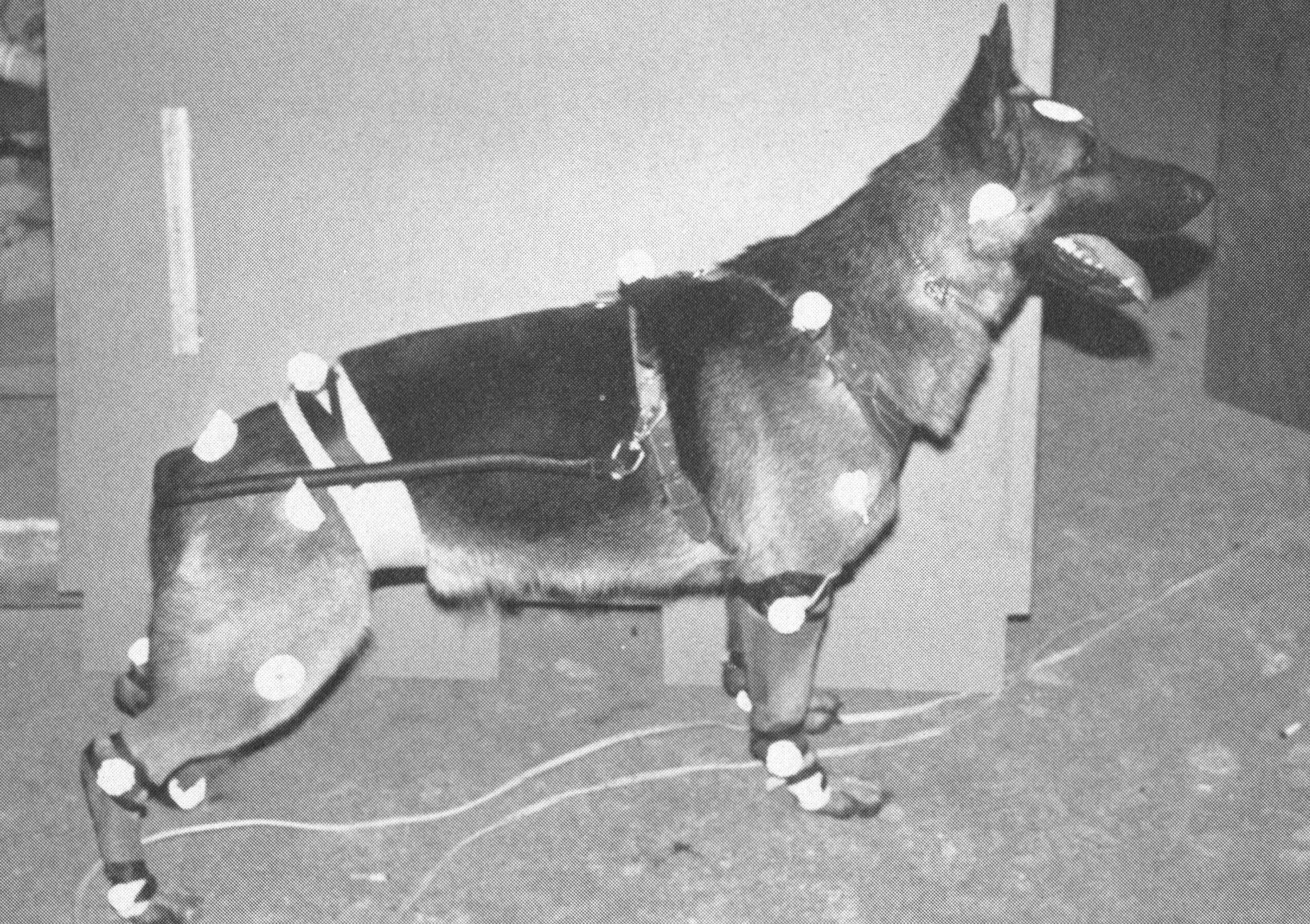

McGovern gathered information for 10 people — including Schwarzenegger— and one dog. "The dog we used was much younger and spunkier than the one in the original footage. He didn't really like the balls. We made bracelets of tape and put the non-stick side of the tape toward his skin. Then we put the balls on with a second piece of tape to avoid getting his fur caught, but occasionally we still caught some, anyhow.

"We had done a lot of people but the dog was very different and very difficult. Among animals with two arms and two legs there are certain similarities, but there are enough differences between humans and dogs in the way the hips and the shoulders work that it was quite a challenge. For instance, dogs' paws are very odd. They flip out at the last possible moment before their toes hit the ground. Until we determined that the movement took about a frame and a half to complete, we had the dog walking with these big floppy feet. It was important that we get it right, because if the dog destroyed the illusion of reality, then nobody would believe Arnold either."

Recreating the original photography was not as easy as it might sound. McGovern gives an example, "For instance, there is an extra walking behind Arnold in one scene. In the chosen take she starts up the ramp with her hands swinging. About halfway through she puts her hands in her pocket and then she takes them out again. We wanted to be sure that she did the same thing again for us. We needed those transition points." The actors had to match their actions to the footage at least as far as the top of the ramp. Once they were behind the screen they could do almost anything. But the transition in and the transition out of the machine had to match. "We had to note which foot they entered with and which arm was swinging where and what kind of pace they were using," said McGovern.

exits the X-ray

unit followed

closely by the

dog.

McGovern's time with the star was limited, but he recalled Schwarzenegger's professionalism was complemented by a sense of humor. "When we were first testing the set-up, we asked him to come by and look at the set. We also asked him to bend over so we could put a ball on his head to see if it fit within the range of the area we were capturing for reference. He thought we were playing a joke on him. Apparently, the set was famous for its practical jokes. He kept looking us right in the eye as we were placing the ball and he watched us very carefully while he was walking around. He was waiting for us to tell him it was a big joke! He couldn't believe we wanted him to wear ping pong balls.

"At the time of the shoot, we were trying to keep as much of his clothing out of the picture as possible. So we asked Arnold to wear black shorts. Somehow, wardrobe never got the message. So when he came on to the set he was wearing a white T-shirt and white shorts. We told him that he needed to change. He said there wasn't time, we'd have to shoot him like he was."

The result was that McGovern's crew was very concerned that they would get unusable data, that it was all going to be wrong. "We were afraid we wouldn't be able to keep his presence down enough to catch the sensors. Turned out to work just the opposite. It paid off to have all the extra information provided by his white clothes. From now on we want actors to wear white when we shoot the reference footage."

Once Metrolight received the sequences in rough cut, they had a much better idea of what was ahead of them. Their biggest fear was that someone would be seen walking into the machine but never walking out. "With the rough cut we could start isolating the reference takes that we had and begin to extract the data. In some cases gathering the information was purely mathematical. In most cases, it was done with rotoscoping. We had film versions of the takes provided by the production company. We had the film made into video disc versions so that we would have a really nice lineup between our choreography program and the video disc.

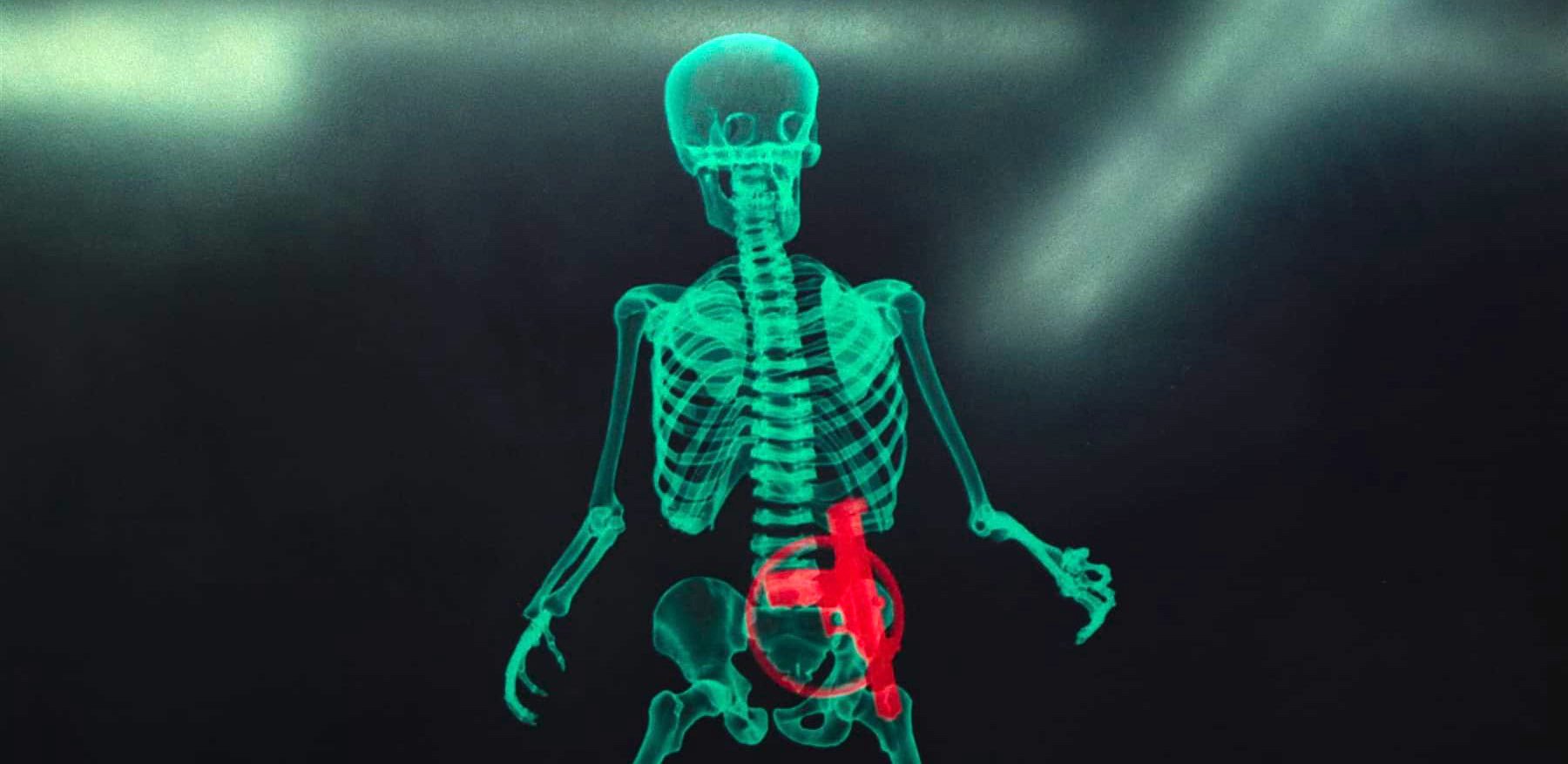

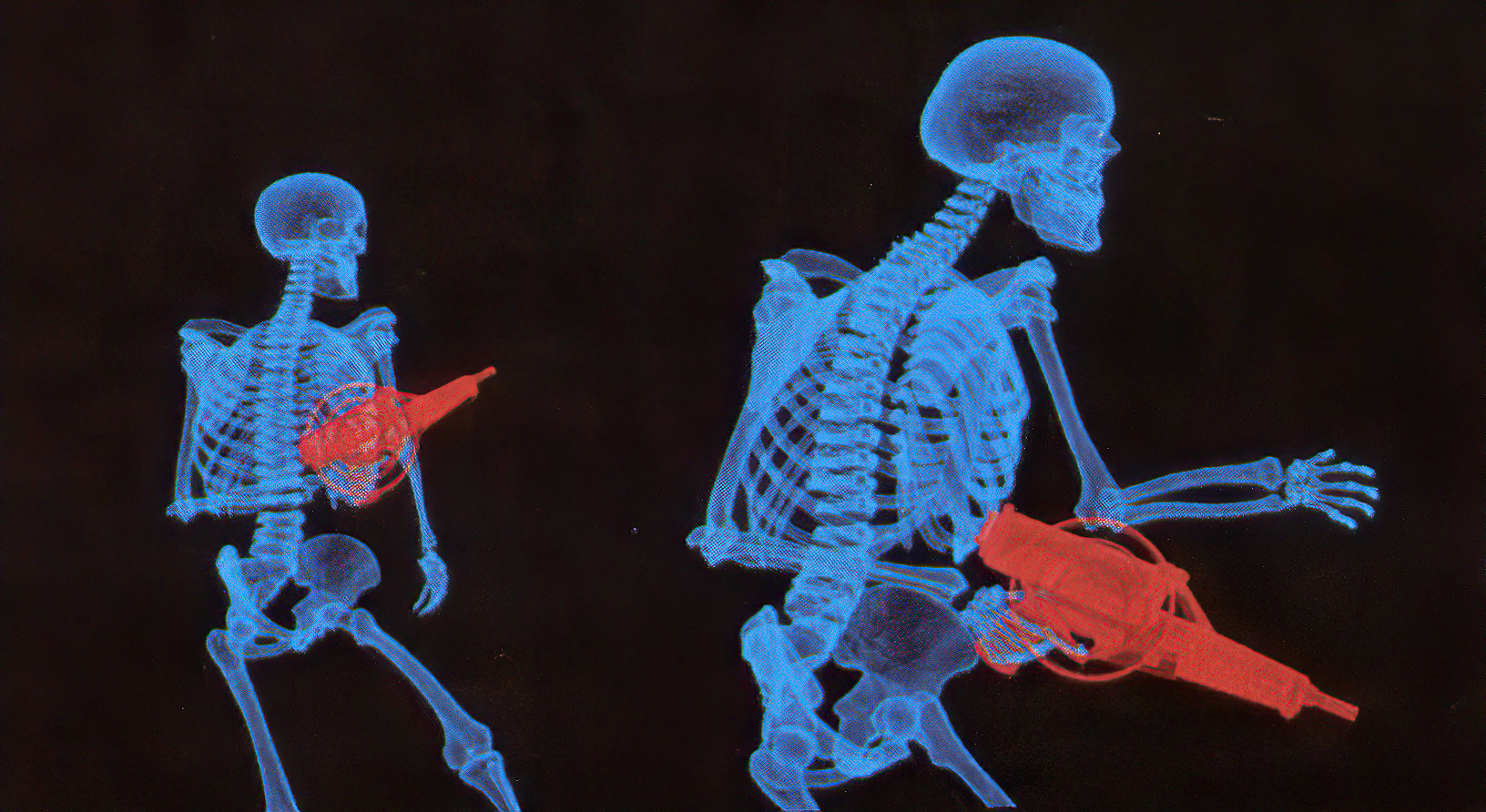

fully rendered

skeleton

animation of

Schwarzenegger

trapped with his

illegal gun.

"There are a lot of levels of refinement that each scene went through. Beginning with a wireframe skeleton, first we matched the motion of the actor. Eventually, we added a matching camera move to the scene. Then after we finished the wireframe for each of the scenes and saw our footage cut in for the first time, we started to see where accurate use of the data got us and where, editorially, we would like it to be different.

"That is the power of the computer — at this point we were able to change the length of scenes by stretching and compressing them. We could actually change the acceleration of Arnold as he burst through the wall. It turned out that the stunt double's motions didn't match Arnold's. The stunt man didn't have to do much acting behind the screen. He stood there in a football stance ready to break through on cue. Arnold, on the other hand, had to look to his right and his left and then make a decision to jump through the wall. The moves didn't match at all. We had to do a lot of manipulating in that scene to get him to reach the same break-through speed that the stunt man had," McGovern said.

We manipulated the data on the guards considerably," he continued. "Initially we didn't like the motion of the guards. Their sequence wasn't long enough. No amount of stretching or slowing of their motion seemed to fix the problem. So we reused data. We actually took Arnold's motion and rescaled it, changed the pacing and used it to slow down the movement of the guards. This ability to manipulate the image is something you just couldn't do with stop-motion models or by reprocessing live action."

While the motion of the skeletons on the screen was the biggest challenge, it was by no means the only one. McGovern and his crew of animators were also concerned about the look of the animation. "The look that Verhoeven wanted was a real-time X-ray. So we made the skeletons look like X-rays the way we're used to seeing them. We used a special light model program that was written for our renderer that allows us to change the center and edge opacity at will. We were able to make the bones look more transparent at the center and more opaque at the edge — just as though they had been X-rayed."

To give the bones an even more realistic look, different opacity maps were used. With all the bigger bones, they needed more information to describe them, so McGovern and crew put a lot of texture maps in to allow veining. "We even had something in there to make it look like the skull contained a brain mass,” he explained.

"We also did some tests putting a skin on the skeleton. Verhoeven was interested in skin, but ultimately decided he liked the very simple graphic look of just the bones. He thought the skin confused the image."

Another component to be considered in animating the skeletons was the movement of the camera: "Before we could do anything, really, we had to be sure that our 'camera' in the computer was aligned the same as the camera was on set. We did that by taking down as much information as we could about the relative position of the camera on set. Once aligned, we actually began the animation with the character's upper body. It's important to get the bob of the body right. Then we attached the arms, legs, head and neck. There was a lot of scaling that had to be done to make sure that our computer skeleton fit Arnold's pose in all of his extreme positions."

In some scenes, McGovern had to match camera motion and camera blur. "We had a whip pan scene where Arnold looks to see what's happening and then the camera follows his eyes," he explained. "In this sequence, we used motion blurring to get our computer images to move more like the live-action. The computer animation can look like bad stop motion when we don't use the blurring technique.

"We also did tests where we actually shot one pass of the live-action and then shot all our animation passes for the different characters and combined them. This gave us something to check how accurate our motion was. We quickly could find out if we were right on, whether the motion felt right and if all the camera moves matched."

McGovern said the one step that the entire process of CGI hinged on was the choice of key frames. "The most crucial thing about this kind of work is deciding where to get the information. What frame is the right frame for the beginning of the step? How can you capture the movement realistically? It isn't just a linear interpolation between positions. To capture the natural way that humans and animals move you have to make very good decisions.

"Once the look and all the motion was okayed by Verhoeven, we rendered all the animation at 2048 x 1366 pixels in VistaVision format to match Dream Quest's use of VistaVision. [See AC, July 1990.] We shot alignment grids at the head of all our sequences and we did tests to see what our animation would look like after it went through the optical process. We knew that what had been approved by the director was great when it was on screen by itself, but we weren't sure how it would look in an optical. We discovered that we had to lower our contrast level quite a bit to match the other elements. We actually gave Dream Quest a number of versions of the shots to work with.

"The thing we were most concerned about was that the skeletons were going to look like they were placed on top of the screen and that it would feel artificial and not seem integrated. Dream Quest and Metrolight came up with a great balance for the animation and the live action — it really felt like the lighting on that front screen was affecting the electronic image that supposedly was emanating from it."

McGovern was pleased with the appearance of the animation on the screen and noted that the X-ray sequence became the centerpiece of at least one trailer for Total Recall. "The degree of resolution we get with our custom Tenderer means that the images show no hint of having been done by a computer. Hopefully, our work supports the storyline in such a way that no one will stop and say, 'Isn't that great computer animation!"'

Instead, they'll think "What a great security system!"

You'll find our complete story on the film’s cinematography here and other visual effects here.