Mobilizing Army of Darkness Via “Go-Animation”

A first-hand look at Sam Raimi’s latest effects-laden extravaganza, which further blazes the trail pioneered by Ray Harryhausen.

By Les Paul Robley

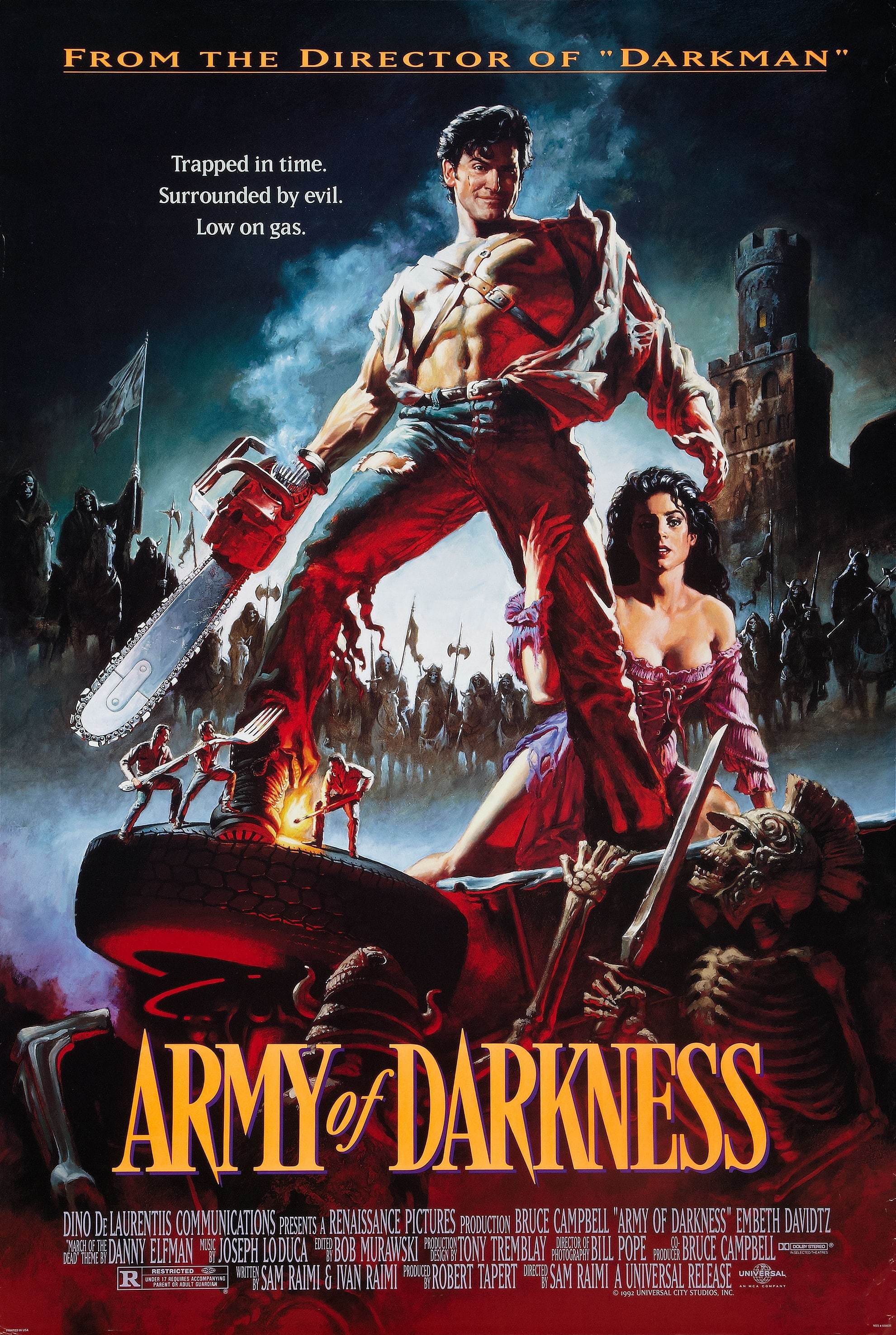

“Army Of Darkness is a rip-roaring, rock ’em, sock ’em, roller-coaster ride of screaming fun and adventure,” says director Sam Raimi of his newest movie for Universal. The film is also the third installment in Raimi’s infamous low-budget cult Evil Dead franchise. The title change was dictated by the studio in order to increase marketability and reach a wider mainstream audience, since this third film’s story hinges more on fantasy-adventure elements than blood-and-guts horror.

Army Of Darkness takes up where Evil Dead 2 ended: the put-upon, cowardly hero Ash (played by Bruce Campbell) is transported by a time vortex into the 13th century. By reading the wrong incantation from the Book of the Dead, he accidentally revives zombie-like legions and must help the locals battle these evil “Deadites” while trying to get back home to the present.

To create the intricate special effects for this $12 million enterprise, Raimi again sought out Introvision International, the company responsible for the effects-laden climax to his prior film, Darkman (1990). “The advantage of using Introvision over other special-effects processes is the incredible amount of interaction between the background, which doesn’t exist, and the foreground, which is usually your character,” explains Raimi. “Because you can see what’s happening through the camera, you can really play with them back and forth and have them interact in a way that traditional bluescreen [traveling matte techniques] wouldn’t allow.”

Normal front projection places the actor in front of a large Scotchlite screen. The projector throws the image onto the screen and the light is retro-reflected back to the camera lens by way of a beam-combiner which places the entrance pupil of the camera lens on the same axis as the projector’s exit pupil. The actor’s body, in effect, masks its own shadow from being visible on the screen. The Introvision system introduces a black-painted matte between the actor and the camera-projector configuration, while the exact negative reverse of the matte is employed between the smaller screen and supplementary lens on the other side of the beam splitter. This enables the actor to appear to walk behind objects in the projected background image.

In order to create the Deadite skeleton army — which rises from the grave to battle the live-action castle dwellers — Introvision opted to eschew the traditional stop-motion approach and perform the process in reverse. Using the former method, pioneered by effects wizard Ray Harryhausen, the filmmakers would have photographed the live action first, and then inserted the ball-and-socket skeleton puppet in front of miniature rear-projection screens via complementary mattes and by back-winding the film in the camera. Introvision decided to shoot the miniatures first and later project the finished plate onto the 60' Scotchlite front-projection screens. The actor was then placed into the “miniature” set using Introvision’s unique, patented, dual-screen projection process.

All of the projected background plates were shot on Eastman 5248 color negative using both Technirama 8-perf and high-speed VistaVision cameras to achieve a high-quality image. This enabled a higher copy ratio of nearly 2 to 1 when the image was rephotographed in 1.85:1 onto standard 4-perf 5296 Eastman stock, resulting in a finer grain and more convincing composite. The high-speed 5296 was chosen as the composite negative since the stock was used primarily in all of the principle photography for Army of Darkness’ night scenes and interiors. Practically all of the animation shots (except for front-screen composites) were filmed with at least two camera set-ups using 8-perf and 4-perf 35mm cameras. This enabled director Raimi to cut to closer views without having to resort to the expensive and time-consuming procedure of re-doing the animation.

Color exposure wedges, in half-stop increments, were made for each shot to determine correct lighting, projector color correction and printing lights. For the previously shot live-action footage, director of photography Bill Pope rated the film slightly under Eastman’s recommended exposure index to obtain a denser negative in the 40s range of printing lights. This was duplicated for all miniature photography, with exposure adjusted accordingly during the shots. Models were always tested for motion whenever motion-control was involved, and focus was often pushed back toward the screen to soften the sharp-edged model, thereby strengthening the blend with the projected background image.

Peter Kleinow, whose many previous credits include RoboCop 2, The Terminator, Terminator 2 and the Pillsbury Doughboy commercials, supervised most of the Go-Animation effects. The motion-control camera operators included Nic Nicholson, Michael Ball and myself. Lighting was provided by Fred Johnson, Ken Thompson and Cosmo Kleinow, and miniature set decorators were Omei Eaglerider and Zuzana Swansea.

The first and most difficult animation sequence undertaken (no pun intended) was a wide-angle graveyard sequence, during which the camera booms up over the hill to reveal the characters Ash and Sheila (Embeth Davidtz) overlooking the vast armies of the dead as they make ready for battle. As many as 50 moving skeletons are visible in the shot, with 15 channels of movement programmed into the Lynx Robotics Motion-Control Spectrum System on an IBM 286 computer. Only six of the skeletons were actually animated by hand in the shot. The four main 12" foreground skeletons consisted of ball-and-socket metal armatures with parts culled from human anatomy model kits. These were animated frame-by-frame by Peter Kleinow, while I animated a 6" grave digger, a sword clopper and two sets of marching skeletons in the background.

The rest of the skeletons were controlled by the computer using wire cables connected to stepper motors. The camera boom and tilt were each operated on two separate motion-control channels, programmed to coincide with the live-action boom filmed later on the soundstage. The entire set was approximately 30' x 40' and constructed in four forced-perspective sections, which were made to appear as if they stretched to the distant hills occupying the furthest table. Capping the illusion was a dark cloud backdrop hung on the stage wall.

This shot, which lasts just 10 seconds in the finished film, took about three days to set up, rig and light, and about 2 ½ days to animate. Each frame took an average of six minutes to manipulate with a three-second exposure time. The long exposure time was not a result of depth of field, but rather speed limitations in the worm gear of the dolly used for booming. The camera was completely surrounded by black gobos, with a movable curtain positioned in front of the lens to prevent stray light leakage in the camera body as a result of the long frame intervals.

Needless to say, the animation process became downright dull after a while. Visitors would come onto the set, see how we were doing, yawn and the leave after five minutes. To keep ourselves from becoming too bored, we often played practical jokes on “Sneaky Pete” (Kleinow's nickname in the Flying Burrito Brothers musical group). Once, when down-loading the camera magazine after a long day of animating, I switched mags surreptitiously with one containing a bogus roll of raw stock. Then I pretended to drop the mag, allowing the film to roll out onto the floor. Pete almost had a heart attack when he saw the full day’s take stretched out on the stage.

Despite the shenanigans, the shot proceeded smoothly enough, with extra care taken between frames when the animation was left overnight. We often didn’t leave until midnight, and the computer’s driver boxes were left on at all times to prevent any backlash movement or gear slippage. As a result, the drivers and motors became hot, so fans were added to cool them down. The entire stage resembled a spaghetti factory of computer cables and wires, with troughs cut in the huge miniature set to enable the animators to reach the models.

In one particularly interesting shot, the four foreground skeletons were made to appear to talk with one another and give a battle cry a la Jason and the Argonauts by syncing their jaw movements to a pre-orchestrated exposure sheet developed by Kleinow. One can even catch a brief glimpse of a sword passing between the two on the right. The miniature 3" sabre was attached to a thin flexible wire positioned on the ground for the three frames it took to travel in midair between the warriors. The wire brace teetered back and forth during the 3-second exposure, imparting motion blur to the blade while rendering the support wire invisible to the camera as it “flew” past the set scenery. In fact, all of the skeleton footage in Army of Darkness contained some form of motion blur — either a motion-controlled camera movement or an actual stepper motor attached to the model — to lend the creatures a natural realistic progression without the stroboscopic look associated with stop-motion animation of the past.

The next shots animated were scenes of the skeletons pulling their dead buddies out of the grave as Ash creeps by. One of them saunters forward with a jaunty air, swinging a shovel over his bony shoulder like a carbine rifle as he joins his mates. The graveyard was softly lit with a large silk above the set and a number of 1/4 and 1/2 CTBs over the lights to simulate moonlight.

For the scene where Ash reads the incantation from the Book of the Dead, the miniature tombstones were rigged with air hoses and filled with Fuller's Earth so they would shoot out of the ground like missiles. Shutters were clamped over a large 10K light and manually operated for lightning effects, while the highspeed Paramount VistaVision camera over-cranked 5248 film at speeds of 96 and 120 frames per second. Obviously, holding depth of field with a 50mm Nikon lens at f4 was only one of the difficulties during this scene. Timings were also critical, since the air jets, lightning, flying debris and dust were all controlled manually without motion control, a strategy dictated by the high-speed rate of the camera.

While this was being photographed, Kleinow prepared the first of the castle battle sequences, in which the humans engage in swordplay with the skeleton legions. One of the skeletons vaults over the wall, loses its sword and its head (in a veiled tribute to Jason), and then frenziedly beats Ash with its amputated arm. To accomplish the effect, the plate of the background castle and skeleton had to be photographed in miniature. Before any time-consuming animation could take place the flickering torches on the castle walls and the waving flag high atop the tower had to be composited in high speed. The castle miniature was only about 6' high, with the furthest tower nearly 15' from the lens. To make the flag flap in proper scale and the fire flicker with small enough flames, the effect had to be photographed in real time at more than twice the distance away from the camera.

Tiny mirrors were positioned on the set in the relative positions where these objects should exist in frame, so that the actual flag and fire could be realized in full scale some distance behind the camera. The set was draped in black, and only the flag and fire were filmed at 36 fps using an 8-perf Technirama camera. Wind machines were added offscreen to provide a waving and flickering effect. The film was then exposed so that the latent flag/fire images could be superimposed over black areas in the miniature castle set. The entire shot lasted 30 seconds, quite long for any animation scene. But over three times this length was exposed in the camera as a precaution in case false starts with the animation necessitated starting over from the beginning. A cap was placed over the camera lens, and the film was rewound back at a safe slow rate to frame zero on the counter. Then the castle was lit accordingly. Naturally, everything had to be locked down for steadiness so that the two "double-exposed" images would not seem to shift against one another on the composited plate. The Technirama G-6 camera body, its intermittent movement equipped with .1866 short pitch Bell & Howell registration, was chained to the animation table.

The animation then proceeded as usual. Motion-controlled cuckaloris wheels were positioned in front of small interactive lights covered with diffusion and half CTO gels to simulate flicker on the brick walls. The first 30 seconds of the scene involved Ash in the foreground fighting a live full-size skeleton. As a result, 720 frames of static castle footage had to be shot first (which took a long 48 minutes at 4 sec/frame) before the animated skeleton reared its ugly head above the castle wall. Upon completion, the plate's negative was safely stored until needed on the full-scale Introvision stage. Here Bruce Campbell would be added via front projection, his action precisely choreographed to match the movements of the skeleton onscreen.

Certain scenes of Ash swordfighting with skeletons were accomplished using traditional miniature process shot techniques. First, Bruce Campbell was filmed in VistaVision on the full-size live-action set fighting nothing. Around him small pyro spark elements exploded to simulate the effect of cold steel blades clashing together. Then, the miniature skeleton was added frame-by-frame in front of the VistaVision background projection of Ash. Scenes where their swords collided, producing a barrage of sparks, involved adding an interactive lighting flash on the puppet. Shots of the four skeletons storming the castle with a log battering-ram employed the Introvision dual-screen method of front projection. For large-scale applications, a supplementary lens reduces the secondary image on the smaller reflex screen. For miniatures this proved unnecessary since the two small Scotchlite screens could be placed at equal distances from the configuration. Complementary mattes were drawn on glass in front of each screen, exactly masking the makeshift bridge so the skeletons would appear to clamber over the moat and strike the castle wall.

This scene involved many intricate problems — not the least of which was aligning the mattes during bright explosion frames — making it probably the second most difficult shot in the animation portion of the film. The mattes were painted on glass by Matsune Suzuki and James Mayeda using the brightest frame as a guideline, since this was where the matte lines would be most noticeable. The log was motion-controlled and programmed to accelerate from half an inch to 1¼ inches of movement per frame. The skeletons were attached to the log, imparting realistic motion blur to their movements. Tiny obstacles were placed in the path of the wooden wheels to give a sense of unevenness over the rocky surface in the plate. Interactive explosion lights were timed using motion-controlled variacs to correspond precisely with the flaming outbursts in the plate. At one point a model tower had to be added to hide a bit of scaffolding, filmed accidentally during plate photography of the large-scale castle set in the San Fernando Valley.

Introvision system, which introduces a black painted matte between the actor and the camera projector configuration. The exact negative reverse of the matte is employed between a smaller screen and supplementary lens on the other side of the beam splitter.

Unfortunately, this added a new set of headaches to the composite since the colors and brick-size had to match precisely, especially when the two explosions went off in frame. Nose-grease was added on the glass to help achieve the blend, in addition to soft-edge cross-hatching of the mattes. Spill light bouncing off the models and hitting the background image on the screen also had to be duplicated on the secondary projection screen carrying the foreground image. The explosion interactive on the model tower had to be exactly matched by eye to the explosion light on the full-size tower in the plate. The variac would rise to full intensity in about three frames, hold at this level for about 10 frames, then slowly decrease in voltage as the explosion in the plate lessened in intensity. A shadow of smoke even had to pass over both tower pieces. To control all the variables, Kleinow needed three hours to animate each one-second, 24-frame explosion.

Another problematic effect involved a scene in which the skeletons drop their makeshift bridge over the moat. Halfway through the shot the skeletons decided to quit; their legs buckled and gave out. The wooden bridge had to be remade out of bamboo since the foursome's thin skeletal arms could not support the weight. A humorous touch featured one of the skeletons “giving the bird” to the humans in the castle, Kleinow's subconscious tribute to the stop motion in Flesh Gordon.

When Sheila is carried off by a Winged Deadite, a pole containing forward-backward and roll movement was poked through the Scotchlite screen. (This is later repaired with a small patch of the same high-gain #7610 material). The model was positioned so that its body hid the rod from the camera. The left-right, up-down flying movements were obtained by panning and tilting the entire camera projector rig so that wherever the background moved, the camera’s field-of-view followed suit. This made the background appear stationary, so that only the puppet appeared to fly in frame. With a three-frame flap of its semi-transparent bat wings — combined with six channels of mo-co movement of the pan, tilt, rod pitch, forward-backward, and camera and projector motors — the puppet carrying the model of Sheila really looked like it was flying away with her. Since the models never actually moved (other than a forward-backward roll), this simplified lighting. Also, the pole through the screen negated any time-consuming aerial brace wires.

Shots of this nature always require that the front projection screen be free of any dirt or defects in material. On static dark scenes, inconsistencies in the screen are rarely seen. But when a shot involves panning or tilting of the background image, even the slightest dirt shows up as a muddy moving smear over the image. Animation of a different sort involved two of the transformation scenes in Army of Darkness. When sweet Sheila undergoes her change to wicked, frizzy-haired Evil Sheila, the 4-perf Mark II Mitchell was bolted onto a mo-co pan-tilt Worrell head. This, in turn, was mounted on wooden tripod sticks and chained to a mo-co dolly track. The film was run at 22 fps (which was the fastest we could run without the camera motor stalling), providing Sam Raimi with the fast-paced, zany look of his two previous Evil Dead films.

A video tap in the camera’s eyepiece helped keep the actress in the same position at the start of each shot. Raimi placed her head inside a wooden vise that looked like a holdover from the Inquisition days, and drew her facial features with a grease pencil on the television monitor’s glassy surface. This way, Sheila could be positioned correctly for the start of each transformation. Motion control enabled the camera to duplicate the same movements during each take, as Sheila’s makeup grew more and more evil. The takes were later optically combined, giving the actress a shape shifting Jeckyll and Hyde appearance. Combining this with a pan, tilt and truck camera movement made the shot look more realistic, at much less cost than the computer-generated morphing seen in most of today’s big-budget effects films.

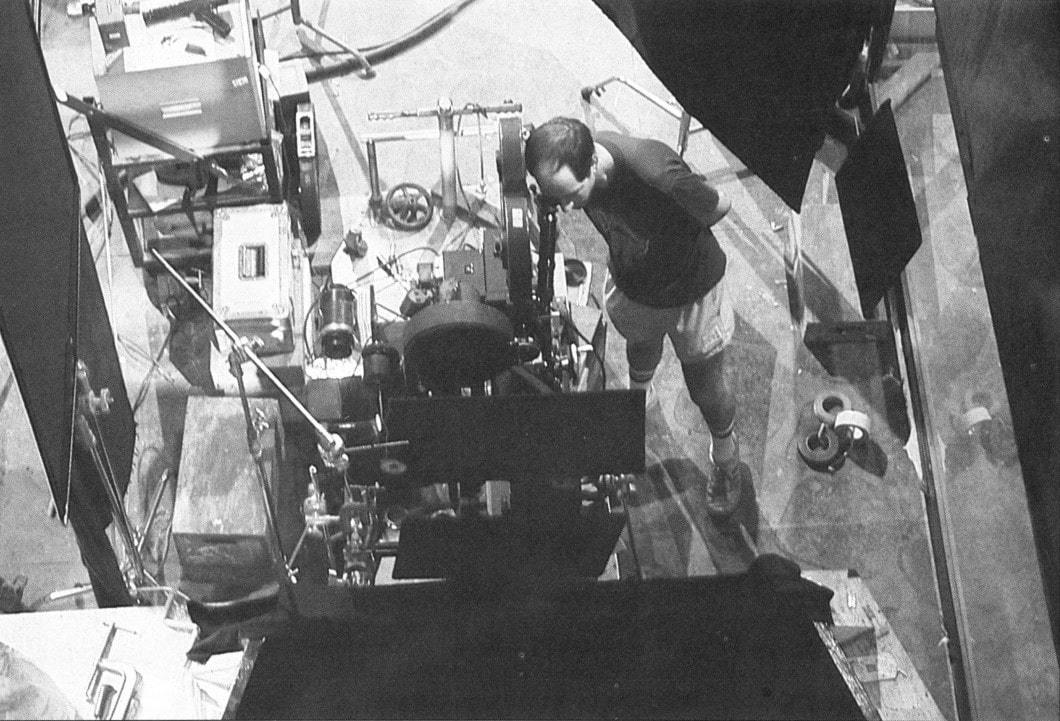

Another transformation sequence involved body parts spewing from the ground and recompositing themselves into Evil Ash. This effect was achieved by an even less costly method. A 4" x 5" negative of the set was made, along with a still of actor Bruce Campbell standing with his back to the camera. These elements produced an 8" photographic cutout of Ash, which was positioned on glass above a 30" x 40" paper print of the set. A single-frame 4-perf 35mm Fox camera looked down from above; the whole configuration resembled an old-style Acme animation crane. To help achieve the blend, some model branches were added in front of the camera lens and a shadow of Evil Ash was drawn on the glass.

The camera was run frame by frame in reverse as I chopped off sections of his body and hand-manipulated, Terry Gilliam-style, the body parts (including fingers) falling into a hole in the ground. The shadow had to be etched away with a razor blade as the legs disappeared into the ground. When seen in forward motion, the appendages appear to explode from the ground, forming the solid figure of Evil Ash. The film then cuts to a live-action, slightly off-kilter angle of Campbell seen in full bloody make-up. Lightning effects were added by gradually overexposing certain frames. Each take of this short two-second shot took nearly five hours to animate.

A 48-frame animated flying fork effect was achieved in similar fashion. When Big Ash's mirrored reflection shatters on the ground, a horde of Little Ashes rise up out of the scattered pieces of glass and try to do him in. In order to fend them off, he picks up a fullsize fork and hurls it at the little men. Areal fork was suspended on wires in front of a front-projection screen, and a VistaVision plate was made by panning the camera quickly over the set to create a blurred background.

In order for the shot to work with a real utensil, the fork had to be hung quite near to the camera. This made the soft shadow of the fork visible on the screen — a problem inherent in close-up front projection. Normally this shadow is eliminated by stopping down the iris in the projection lens (if so equipped), thereby collimating the projected light beams to the screen and sharpening the image. But when the object is too close to the camera-projector configuration, light is diffracted around the object, resulting in an apparent fall-off in the intensity of the image on screen and producing a fuzzy shadow around the object when viewed through the eyepiece. What looks like a poorly-aligned camera-projector nodal lens position is, in fact, this halo-gradient. And no amount of xyz tweaking of the camera alignment will completely eliminate it. One can hide the “shadow” by forcing the camera lens toward the beam splitter, but this only works when the object is dead center onscreen. When the object travels left or right or up and down in frame, the shadow appears on the inside edge closest to center.

To avoid this problem in Army of Darkness, the beam splitter that normally sat at a 45-degree angle between the camera and projector was replaced by a large piece of float glass and re-positioned at a 45-degree angle between the fork and the screen. The VistaVision projector (still at right angles to the camera) then reflected its image from the glass, onto the screen, and back into the camera lens, thereby preventing the fork's shadow from falling between the projector lens and the screen. The wires holding the fork disappeared by slightly swinging the utensil, pendulum-like, during the two-second exposure, thereby giving the prop a nice soft blur.

Scenes of the Siamese-twinned Spider-Ash scrambling through the forest were created by mounting the puppet on a moco dolly track and programming it with random jerking movements through a miniature forest set. The rod holding the puppet protruded through a slit in the ground which had to be covered by Kleinow after every frame of movement. The camera boomed through the trees, following the puppet's action with sinusoidal pan and tilt movements. This random motion was pre-programmed for frequency and intensity utilizing Lynx’s “Wheels” function to resemble a human operator running a pan and tilt head — not a precise duplication of the model’s motion-controlled travel. Realistic motion blur was likewise achieved. Kleinow animated one of the “spiders” slapping the head of the other in a comical send-up of Raimi’s beloved Three Stooges.

The final animation scene filmed revolved around a feisty flying Book of the Dead that attacks Ash. Right before he says the magic words — “Klaatu, Barada, Nikto” — the Book opens its mouth, crunching his fingers. He hurls it away, but the Book magically flaps its bindings like a butterfly, diving upside-down to fly back at our hero.

The effect was achieved using two smaller, identical, quarter-scale Books of the Dead — jokingly referred to as “The Paperback Editions.” One had a ball-and-socket joint on the inside and the other contained one on the spine. Each book was rigged in a similar fashion to the Winged Deadite, with six-channels of movement: camera projector pan and tilt to simulate a side-to-side, up-down flying motion; rod forward and backward roll to make it fly toward and away from camera; and a separate zoom and nodal-point camera tilt control giving the effect of a slight boom up as the Book flew to the top of the frame. The books were interchanged as necessary whenever they needed to fly in a complete 360-degree loop. The pages were animated to flip page-by-page when the Book flew near camera.

The pages were color Xeroxed from the original book and printed to the correct scale. They were also stuck together with sticky wax and paper tape in order to animate on cue. The covers were glued to hinged metal sheets which flapped like bat wings in three-frame intervals. The projector had to be manually advanced frame-by-frame, however, as all six channels on the driver box were already occupied. The frantic movements necessitated that each take be shot at an f/16 with two seconds of exposure for maximum depth of field. As the rod holding the book moved toward camera, a guide wire was added to prevent it from sagging. Careful flagging of lights hid the wire by making it go to a thin black silhouette in front of the high-gain Scotchlite screen.

The windmill exteriors were all shot in miniature; the rotating blades, tree and camera movements were programmed via the computer. For a shot where Ash turns around and sees himself in the doorway, a small transparency of Campbell was positioned in the mill’s door with a light behind it. Later, Campbell was filmed before a front projection screen in the usual fashion. Shots where Campbell confronts his evil self were filmed in the same way.

These new and exciting variations on traditional animation techniques mark the next steps on the road paved by Ray Harryhausen. With this extensive application of go-animation combined with large-scale front projection, the stop-motion animated look of the past has been given an important update.

Of note, the film’s director of photography, Bill Pope, who also shot Raimi’s sci-fi-horror thriller Darkman, would later collaborate with the director on the superhero films Spider-Man 2 and Spider-Man 3, and go on to photograph the Matrix trilogy and Team America.

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.