News of the World: An American Journey

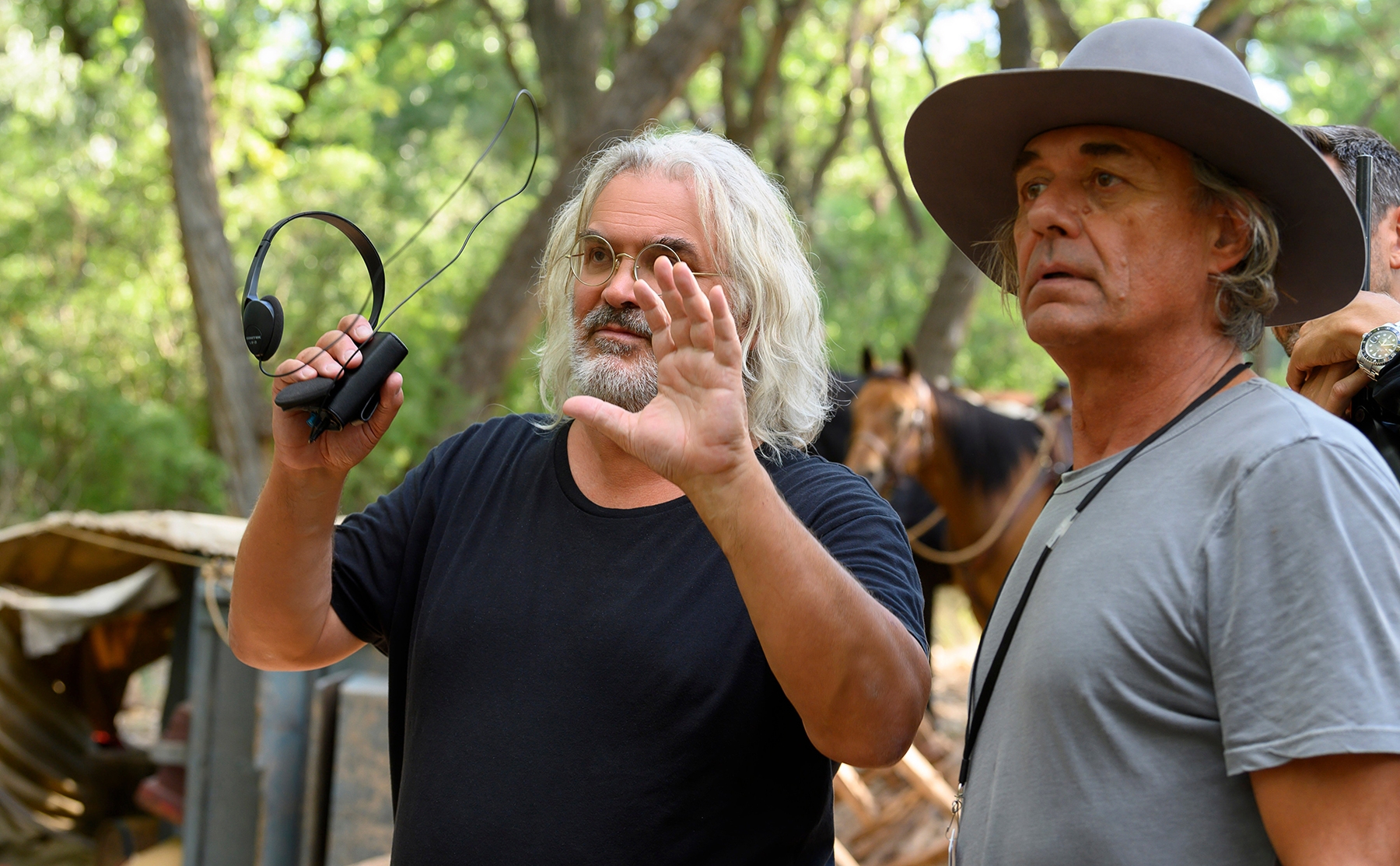

Dariusz Wolski, ASC helps director Paul Greengrass leave his comfort zone for this dramatic Western.

Unit photography by Bruce W. Talmon, courtesy of Universal Pictures

When director Paul Greengrass took on the first Western of his career, News of the World, he decided the material called for a departure from the “comfort zone” of his famed kinetic filmmaking style. Based on a novel by Paulette Jiles, the Reconstruction-era drama tells the story of a Confederate war veteran (Tom Hanks) who is traveling through Texas — reading newspapers to townsfolk to eke out a living — when he comes upon an orphaned white girl (Helena Zengel) who needs to return to distant relatives after spending most of her life raised by a Kiowa tribe. The rugged journey to bring her “home” across a harsh yet beautiful landscape, and the evolving relationship between the unlikely pair, form the emotional core of the story.

Best known for directing three films in the Bourne action series and the historical thriller United 93, Greengrass quickly realized the challenge he faced was how best to “do things a little differently yet still make it feel authentic to me,” he says. To accomplish this, he called upon cinematographer Dariusz Wolski, ASC — whose credits include the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, The Martian and Alice in Wonderland (2010) — to collaborate with for the first time.

“When you make films, you have to change and grow,” Greengrass says. “I love the movies I’ve made with [longtime collaborator Barry Ackroyd, BSC]. He’s a dear friend, and I’m sure we’ll make more films together in the future, but I wanted to explore a different style of filmmaking. I’ve loved Dariusz’s work for years, so I spoke to him, and told him I wanted to be challenged. I wanted to do things differently — and that’s what we did. [We came] at the material with different instincts and backgrounds.”

Both filmmakers agree that one inspiration for their approach, thematically and visually, was John Ford’s classic Western The Searchers. Greengrass, a self-described Ford fan, explains that News of the World is, in a sense, “The Searchers in reverse, because in that movie [John Wayne’s character] is going to find a girl so he can get her home, and in this film, our character has already found the girl and is trying to bring her home.”

Wolski examined other Westerns he admires, including Andrew Dominik’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (AC Oct. ’07) — photographed by Roger Deakins ASC, BSC — which served as another inspiration. “[Roger is] such a master of lighting with the way he utilizes natural sources,” Wolski says.

Early on, Greengrass talked extensively with Wolski about how best to maintain his preferred “unknowing camera” — which he defines as a camera that “doesn’t know more than the characters in the story.” They also discussed how to find a visual language that would allow them to “shoot a classical Western that honors the landscape and the intimacy of the characters — the two different poles of the story,” he says. The result, according to the director, is “a film of stunning beauty with a certain muscularity to it as we traveled through the landscape, as opposed to a passive follow of these two characters.”

The filmmakers’ differing viewpoints were essential to the success of their vision. “Paul takes a documentary approach and makes movies from the direct perspective of the main character,” Wolski says. “I come from a different background, having worked with Tony and Ridley Scott, Gore Verbinski, and Tim Burton, who are extremely visual directors. The question I faced was how to take the documentary approach and turn it into something a little bit more visually arresting.”

That challenge, combined with a modest budget and the rugged shooting locations throughout New Mexico, led Wolski to suggest that the film be shot entirely with a combination of handheld and Steadicam techniques. For conversations and non-action scenes, the camera was always handheld, and “for big tracking shots and long walking shots, we decided to go to Steadicam to kind of calm it down a bit,” the cinematographer says.

Wolski chose Arri Alexa LF and Mini LF cameras, Angénieux Optimo EZ1 and EZ2 zoom lenses, a Panavision Primo 11:1 zoom, and Panavision System 65s. “The EZs pretty much covered us for the range of shooting,” Wolski says. “We had the Primo for the occasional long-lens shot, which, of course, a Western calls for. I always used the [System 65] primes at night; they’re super-fast and a little soft, and they flare nicely.” A-camera 1st AC Dan Ming adds, “We shot wide open at night and mainly at a T5.6/8 during the day so we had room to open up when the inevitable clouds would roll by.”

Ming notes that because of the locations and the nature of the story, the logistics were “inherently more challenging” for pulling focus. “Actors were on horseback, [in a] wagon, swimming or walking — situations where marks aren’t really practical,” he says. “We were frequently just running around with small monitors and handsets with a Preston Cinema Light Ranger overlay to give us distance readings. Dariusz is not one to shoot everything wide open, and the natural surroundings and sets gave a lot of texture to the story, so it was nice to be able to see it and not have it all be soft with a super-shallow depth of field.”

The camera was never locked off during production. “We covered the majority of actor and wagon movement with the Steadicam — a very demanding assignment for [B-camera 1st AC] Simon England, who made it look easy,” says Steadicam operator James Goldman. “We did a lot of walking with the Steadicam because we did not carry a dolly, Technocrane or pursuit vehicle for the entire show. Most of the news-reading scenes were covered with three handheld cameras, as were the other longer stationary dialogue scenes.

“Key grip extraordinaire Mike Popovich converted a Dodge Ram 1500 truck into a shooting platform via speed rail,” Goldman continues. “That allowed us to mount two cameras simultaneously — [A-camera operator] Martin Schaer handheld and me with the Steadicam from the back or front. It was a low-budget approach that worked very well for leading and following shots where terrain allowed.”

The shooting environment required a mobile run-and-gun setup, reports digital-imaging technician Ryan Nguyen. He used a combination of Teradek Bolt 3000 XT transmitters and receivers, and a proprietary fiberoptic system designed for him by Panavision to manage the camera signal. “Because we were shooting in the mountains with multiple cameras in all directions at any given time, it was very hard to hide the receivers and the video village,” he says.

“We weren’t on a soundstage —

we were out in the middle of the desert,

doing it like a proper Western.”

“I found it easier to place the receivers as close to the cameras as possible, and from there I would run a BNC cable to the on-set fiber box and then run a single fiber cable back to my station. I find that fiber is an essential tool for video workflow on set, even when using wireless.”

Nguyen adds that he built a mobile rack for the production that housed a BlackMagic Design router, four TVLogic IS-Mini LUT boxes, a Decimator quad split and a Convergent Design Odyssey 7Q as his “go-to device to grab reference and use as my waveform and vectorscope, and for false color.”

“We [understand that] one LUT doesn’t always work for every scene, so we are always playing a bit with CDLs on set,” Nguyen adds. “[Dariusz and I] really like to start off by seeing what the set and environment give us, and once you embrace that, the color and look comes naturally. “EC3 and Company 3 then handled our dailies creation, using the ASC CDLs I provided. Dailies were viewed using a Pix system, but if Dariusz ever wanted to see something on a bigger screen, I had a setup back at the hotel.”

The movie features “a lot more Steadicam than I’m used to,” Greengrass notes, as well as some helicopter aerial work that Wolski says the director was originally opposed to “because he believes everything should be shown from the perspective of the character. But in the end he [agreed] because it was important to open the movie up and show the characters in the landscape, which is also a character in the film.”

When it came to a crane-mounted camera, however, despite a long history of classic crane shots in many famous Westerns, Greengrass was insistent that News of the World eschew the technique entirely. “Cranes would take me too far away from my vernacular,” the director says. “A sweeping crane shot as you often get in Westerns would have introduced us to the ‘knowing camera,’ and I didn’t want that. It can be beautiful if you do it properly, but it didn’t feel like my language. Dariusz agreed with that, and yet he was relentlessly searching for a Western-composition way of viewing the landscape to help us reach those two poles — the intimate drama identity in the center of the film and having that [take place] inside this enormous, unforgiving landscape.”

The picture features a classic action sequence, beginning with the two protagonists fleeing into the mountains in a rickety wagon as villains try to run them down. The wagon crashes spectacularly — and a cat-and-mouse, tension-filled shootout ensues in and out of the rocks and crevasses of the landscape. The sequence was extremely complicated to shoot safely in the mountains at about 7,200' in elevation.

According to Greengrass, the idea was to construct a “long-flowing action sequence. It starts as one thing, a wagon chase, and then becomes a foot chase, and then becomes a gunfight, and then we go to the resolution. Dariusz and I both were struck with the textures of the [mountain location] — all the dust, sand and stone. It was a brutal and dramatic visual palette to set the sequence in. There were also a tremendous number of safety issues associated with that sequence, particularly when we got really high up. It would take a couple of hours to get everybody into position to shoot, and then a couple more to come down.” The director adds that Wolski is “indefatigable in reaching a place where he can get the shot that he wants. It was a real adventure for us, and a lot of hard work."

Wolski notes that the filmmakers “had to cheat two different locations” to make the scene work, because they couldn’t bring a wagon or horses high into the mountains. “We shot the ‘beef’ of the scene with the main actors first,” Schaer says, after which the operator led a 2nd unit that shot material featuring the villains to tie the action together.

“We used three handheld cameras for the action sequences almost all the time — that gave us plenty of angles and action,” Schaer continues. “For the shootout, Paul and Dariusz chose a location below a dramatic cliff [that was] only accessible by foot, not even by mules or horses. For a few weeks, a team of motivated two-legged ‘goats’ — aka crewmembers — made an early-morning ascent into the gnarly rocks to set up and create an exciting sequence amid this spectacular Western Range.”

Goldman adds, “For much of the battle we were perched on the sides of steep hills, handheld, wrestling to get shots. Shooting the overs from the top down toward the villains at the bottom was handheld at the knees, as the actors took cover low and popped up to shoot.”

“When something beautiful happens,

just be ready to capture it.”

One element of the environment the filmmakers couldn’t possibly control was the New Mexico sky. For one key sequence, the production created a practical sandstorm to pelt the protagonists using gas-powered propeller fans. It was an effect, he says, that worked very well — and was then augmented by Mother Nature herself.

“We created the sandstorm, and then we realized we had super-dramatic dark clouds behind it,” Wolski re-calls. “It was spectacular. [In the movie], when the sandstorm subsides, you see this very dramatic sky in the background. That was all real. My philosophy has always been to be open to nature and don’t overplan it."

Intending to avoid movie lights as much as possible, Wolski worked with gaffer Orlando Hernandez and set decorator Elizabeth Keenan to select 100 period kerosene fixtures for use throughout the shoot. (Additional lamps were used to dress backgrounds.) For safety reasons, any lamps not close to or held by characters were converted from kerosene to electricity. “We used 12-volt DC LED controllers [generally one per lantern] with 50-, 75- and 100-watt halogen bulbs, and that also gave us the ability to control LED tape installed on the lantern hoods and such to augment the output,” says Hernandez. “This was my first time using a 12VDC system for lanterns instead of 120VAC, and this approach eliminated the need to run miles of Socapex cable and install elaborate dimmer stations throughout the towns. It also allowed us to place lanterns in the shot at the last second. Our console programmer, Patrick Toohey, set the intensity level and applied a slight flicker to these units to mimic the occasional flutter of a kerosene lantern.

“Night exteriors and firelit scenes employed custom 530-watt 2'x4' LED hybrid panels that I built for this film,” Hernandez continues. “We added Half CTO gel to create a warmer glow below 2,600K. These panels worked as softboxes mounted in condors, attached to ceilings, and mounted on stands, and smaller versions were used whenever a light source needed to be concealed.”

HMIs were used for day interiors, to backlight rain for some of the daytime tank work, and to occasionally augment natural daylight on exteriors. Arri L-Series and SkyPanel LED units were occasionally used for night interiors — with SkyPanel S60s “sometimes also providing fill for exterior and interior day scenes.”

Wolski used classic film lights “as little as possible,” he says, relying on natural light for day exteriors, and real or enhanced firelight and kerosene lamps at night. The goal for the interior work was to make the scenes “as realistic as possible just using gas lights, making it moody and kind of mysterious — representing that period.”

Apart from “a few beautiful wide shots,” the film is very intimate, Wolski adds. “It’s shot in close-ups — it’s about close-ups. Most conversations happen either on the wagon or by the campfire — that’s where we get reflective, emotional scenes. The campfire gave us a great opportunity for intimacy, especially when you try to do it during magic hour with real flames, hardly augmenting anything. On the one hand, this is a big land-scape movie, but on the other, we are talking about two faces in the middle of nowhere. And that makes it a very emotional movie.”

2.39:1

Cameras: Arri Alexa LF, Mini LF

Lenses: Angénieux Optimo 45-135mm EZ1 T3 and 22-60mm EZ2 T3 (both with FF Rear Optical Block); Panavision Primo LF Zoom adapted to 40-470mm T4.5, System 65

Wolski also spoke to interviewer Shelly Johnson, ASC about his work in the film as part of our Clubhouse Conversations discussion series: