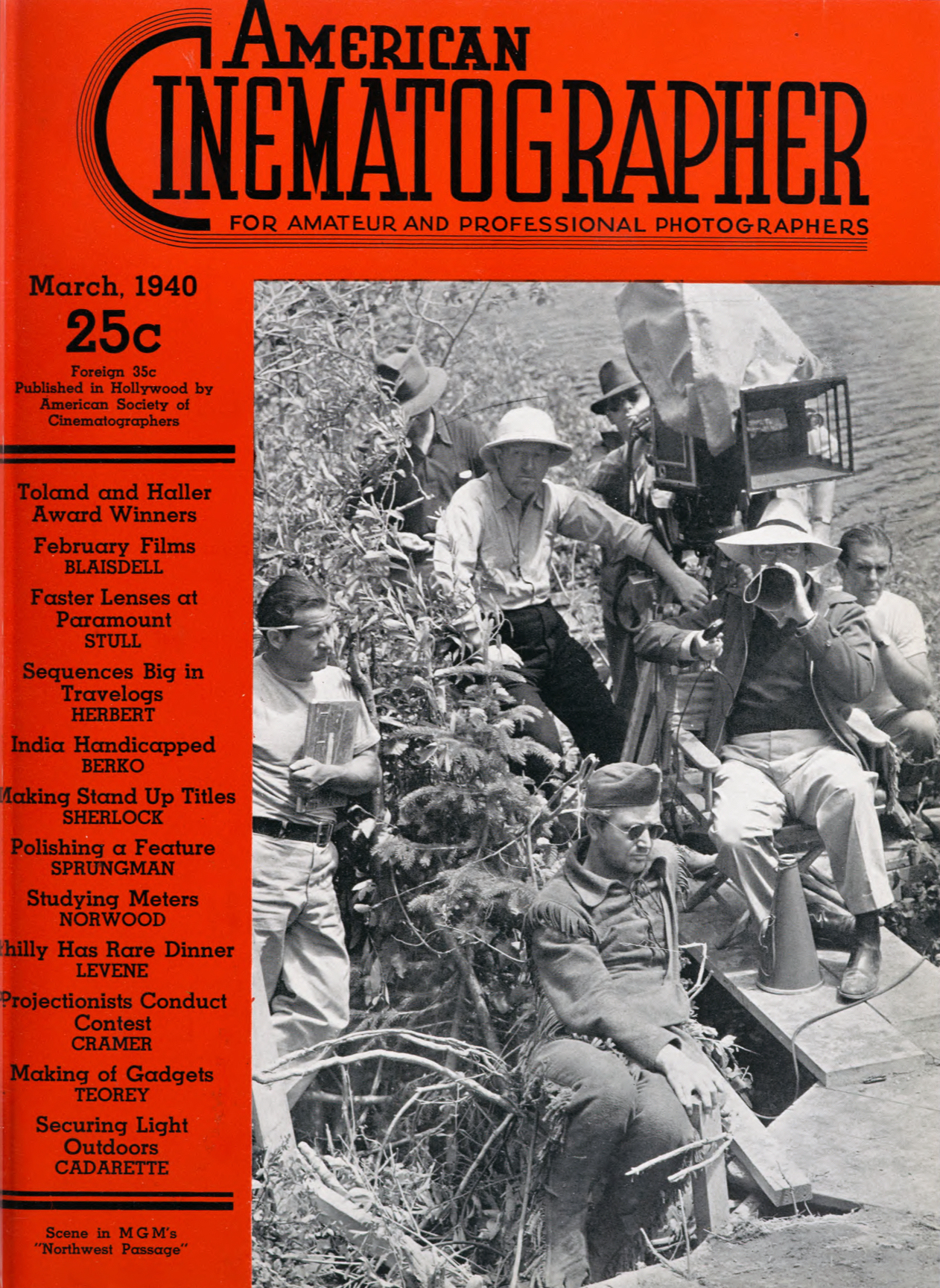

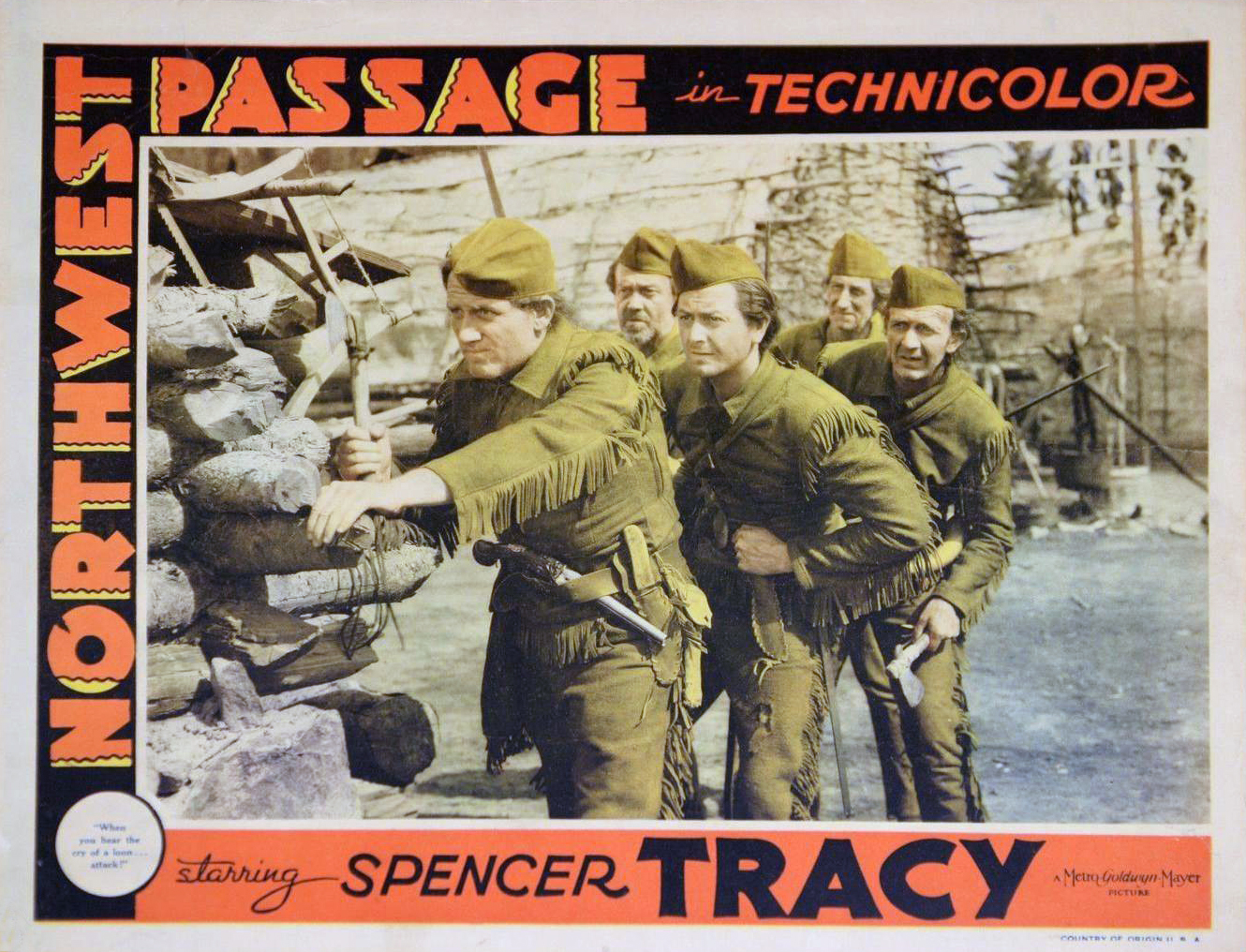

What Work Went Into Northwest Passage

An accounting of the amount of preparation and production that went into shooting this 1940 Technicolor adventure.

Giving something of an idea of the enormous work behind a great motion picture, MGM prints a story of 6,000 words in its souvenir program describing how Northwest Passage was prepared and made. The company probably would be well repaid should it reprint this tale in pocket form and furnish it to exhibitors for distribution.

New York’s MGM story department read the galley proofs of the Saturday Evening Post’s serial “Rogers’ Rangers” on November 5, 1936, and recommended its purchase. On June 25, the story was printed in book form (by Kenneth Roberts), subsequently selling 500,000 copies.

On September 23 the tale was purchased by MGM. That was 1937.

Immediately following the story’s purchase a location crew started a hunt. The original locale, Quebec Province, was found too well-settled. The search shifted to the Pacific Northwest, with the same result. Then the ideal spot was discovered in Payette Lake, Idaho.

March 29, 1938 - Spencer Tracy was cast for Rogers.

June 7, 1938 - A crew went forward, but six weeks later the location was abandoned on account of inclement weather. In May and June of last year a crew was sent to Idaho to rebuild exterior sets and prepare camp.

July 6, 1938 - Following the arrival of the entire cast, camera work was begun, and was continued in Idaho until August 19.

Indians to the number of 364 were brought from seven reservations of the Northwest. There was a Hollywood cast and crew of at least 250. There had to be housing space also for 500 extras as well as room for an entire studio in miniature.

Teletype with Hollywood

Showers, heaters and toilets were installed in 40 log cabins and two frame dormitories. Huge circus tents were erected to house wardrobe, make-up and property departments. Other log and frame buildings were set up for electrical, camera and sound equipment. The former main lodge, now the commissary, was staffed by a Hollywood catering crew.

In a business office alongside the commissary a teletype, the first to be used on such a location, was installed to keep the troupe in instant communication with the production department at the studio, some 1,350 miles away. Power for its operation, and for the lighting of the camp, was provided by a hydro-electric plant, also specially installed.

Three automobile-type boxcars were brought from the studio containing costumes for 250 British soldiers, 240 Rangers, 200 French soldiers, 200 oarsmen and 400 Indians.

Each of the 240 Rangers had three “stages” of uniforms: nearly new, partly torn, and in shreds, to represent different stages of the trek. And because of the rough usage which these uniforms received among pine branches, underbrush, etc., each Ranger had four changes for each stage, or 12 in all. Properties with an estimated value of $55,000 were scattered over the Idaho landscape.

To transport cast and crew to and from water locations a veritable navy was necessary. Four huge barges, one cabin launch and four open launches, one 18-passenger speedboat, one smaller speedboat, 17 whaleboats and Bateaux, two Indian war canoes, and every other rowboat which could be rented or commandeered carried men and equipment.

The most elaborate outdoor set was the Indian village of St. Francis, erected on the upper Payette River between towering granite cliffs. Comprising 125 separate buildings, it covered 10 acres cut out of the virgin forest.

Planned Conflagration

Because the charred interiors of every building at St. Francis had to be visible after the Rangers had set fire to them, it was necessary that every wall be finished from ground to roof. Forty thousand feet of copper tubing was laid underground and gasoline driven through it by two compressors, to be sprayed through tiny nozzles fastened behind doorframes and under windows.

From a 70' tower built like an oil rig behind the village, field telephones instructed men in dugouts below what sections to fire and what to control. The Rangers tossed flaming torches onto roofs and against walls, but the gasoline was necessary to insure a rapid conflagration. The firing of the gas was done electrically from keyboards in the dugouts.

The final conflagration scene, which shows the Rangers crossing the river by canoe as the last flames rise behind them, required 800 gallons of gasoline and 1,200 gallons of kerosene, poured directly onto the remaining charred framework, for by now the copper tubing had melted. The entire C. C. C. McCall division stood by to prevent the fire from spreading into timberland.

The only suggestion of accident occurred when a gust of wind blew flames across a camera parallel, causing director King Vidor and cameraman Sidney Wagner, ASC and their assistants to jump to safety, singed but not badly hurt.

In addition to Wagner, the company's director of photography, William V. Skall, ASC, headed a Technicolor crew of 16. Exposed film was taken by camera truck to Boise each night, whence it was flown to Hollywood for processing. The prints were then flown back to location and shown in the improvised projection room.

The complete shooting time was 70 days, of which Spencer Tracy worked 69 and Robert Young 68. The recording of the score required a 60-piece symphony orchestra and a male chorus of 60, working for an entire week.

The most picturesque set built for the production and one of the most notable in any picture was that of “Crown Point.” Containing 110,000 board feet of lumber, the building was 200' wide, 300' long and averaged 40' in height. Six acres of state forest land were cleared for the site.

The two cinematographers shared an Academy Award nomination for their outstanding camerawork.