Cracked Reality: Nothing Lasts Forever

Cinematographer Heloisa Passos, ABC, DAFB draws inspiration from narrative filmmaking for this documentary about corruption within the international diamond trade.

Photographed by Heloisa Passos, ABC, DAFB and directed by Jason Kohn, the Showtime documentary Nothing Lasts Forever is a globe-trotting investigation into the origins, and maybe the undoing, of the international diamond trade. With stops in America, Botswana, China and India, the filmmakers follow beleaguered gemologist Dusan Simic, as he attempts to warn his peers in the industry that artificial diamonds are being mixed with mined, natural diamonds. Along the way, we meet diamond skeptics, chemists, merchants, moguls and miners, all of whom are living very different — and very personal — diamond-shaped lives.

In Nothing Lasts Forever, Passos and Kohn replicate the chemistry of their 2007 documentary Manda Bala: Send a Bullet, in which Passos’s bright colors, strong compositions, and subtle camera movements flawlessly complement Kohn’s direction. “We have a good relationship, and it shows,” asserts Passos, whose work on the film won the 2007 Sundance Award for Excellence in Cinematography.

American Cinematographer: Heloisa, you have the first production credit in the opening titles of Nothing Lasts Forever, which to me, indicates a very close collaboration on this project.

Heloisa Passos: I've been on this project for so long that I'm a co-producer. Ten years ago we started it with small grants from the Tribeca Film Festival and Catapult Film Fund. Our original idea was for a project about artificial life and artificial gems, but when Jason met our protagonist, Dusan Simic, it became apparent that there was a separate story to be told about man-made diamonds.

The film feels a bit like an international thriller, the way it tracks the diamond trade across different locations in United States, in Africa, in England, India and China. There’s a carefully constructed quality to the cinematography, and in the way the stories weave in and out of each other.

We were thinking about the intersection of film noir and science-fiction. We talked a lot about the original Blade Runner [shot by Jordan Cronenweth, ASC] for the sequence in our film where Dusan is driving an Uber to LaGuardia Airport. It was cloudy, super humid, a bit rainy. For the cinematography, these textures were amazing. I set up an Alexa Mini with an Angénieux Optimo Anamorphic 56-152mm on a Ronin 1 stabilizer and shot it at twilight to heighten the suspense and mood. We also tried to think of our documentary as a globe-trotting James Bond film — an adventure in a foreign location, driven by mystery and intrigue. In postproduction, one of our visual references was the warm tones of the movie Her, by Spike Jonze [shot by Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC]. It’s interesting that the references for this film aren’t necessarily other documentaries, but fiction.

There’s this motif that runs throughout the film where everyone you talk to you does doesn’t just have information to share about the diamond trade, they have a story to tell, or a dream to spin around this idea of what a diamond is or represents. What influence if any, do those stories have on your approach to storytelling?

It’s very important to understand that this is a film about capitalism. Our aesthetic challenge was to never present diamonds as an object of desire, but something more complicated, because it’s also about money. Behind the money, there’s war. And when it comes to artificial diamonds, it’s a lie about a lie. Diamond ads all talk about the heart, but to me, the diamond trade is heartless.

Another motif that seems to run throughout your work with Jason is the use of wide-angle lenses for the vérité material, as well as the seated interviews, to the point where the lines of the image are distorted around the edge of the frame. What can you tell us about this approach?

“It’s about breaking reality, and the reality is brutal. We’re talking about capitalism in the context of absolute inequality.”

For most of the interviews we shot two cameras, side-by-side, one with a Cooke Anamorphic/i SF 25mm or 32mm prime and the other with the Angénieux Optimo Anamorphic 56-152mm zoom , with the interview subject centered in the frame. Our challenge was to keep the cameras as close as possible to preserve a consistent eyeline. We like the wide angle because it allows us to get close to the person who’s being interviewed. Jason sits next to the camera, no more than one and a half to two and a half meters from the subject. The focal length of the zoom was dictated by the distance of the subject to our prime lens.

There’s something distinctly un-documentary-like about the choice to go so wide. It calls attention to itself.

It’s about breaking reality, and the reality is brutal. We’re talking about capitalism in the context of absolute inequality. The diamond is a symbol of traditional notions of family and property and power. We wanted to call attention to these notions and deconstruct them.

I really appreciate the use of the split diopter for certain shots, which, apart from looking really cool, lends a kind of refracted quality to the image and again kind of calls attention to the fact that you’re viewing it through something.

The idea to use Schneider +2 split-field diopters is the same idea as using wide angle lenses — to break reality. Also, I’m always looking for windows and reflections to shoot off of. I love bringing these techniques from other films, particularly narrative films, to my documentary work.

What influence does the way you want to tell a story have on the camera you choose?

We wanted to make this film with an Arri camera, but it was impossible to have one all the time, so we ended up using different cameras — Alexa Mini, Sony A7S and A7SII, and Sony F55 — which made postproduction a challenge. What’s more important to me are the lenses. If I use the same lenses, I have enough to work with in the edit. If I have different kinds of lenses, then I’m going to have a problem. Our goal was to maintain a consistent look throughout the film, but because it took so long to complete, this was difficult, and required more time in color correction to match lens characteristics, especially contrast levels.

Did you use the same lenses throughout the film?

We wanted to shoot anamorphic all the time, but that wasn’t possible. If I had to re-frame a shot in post, Cooke S4/i primes would give me the best quality to mix with the anamorphic lenses, but we only used it for one interview.

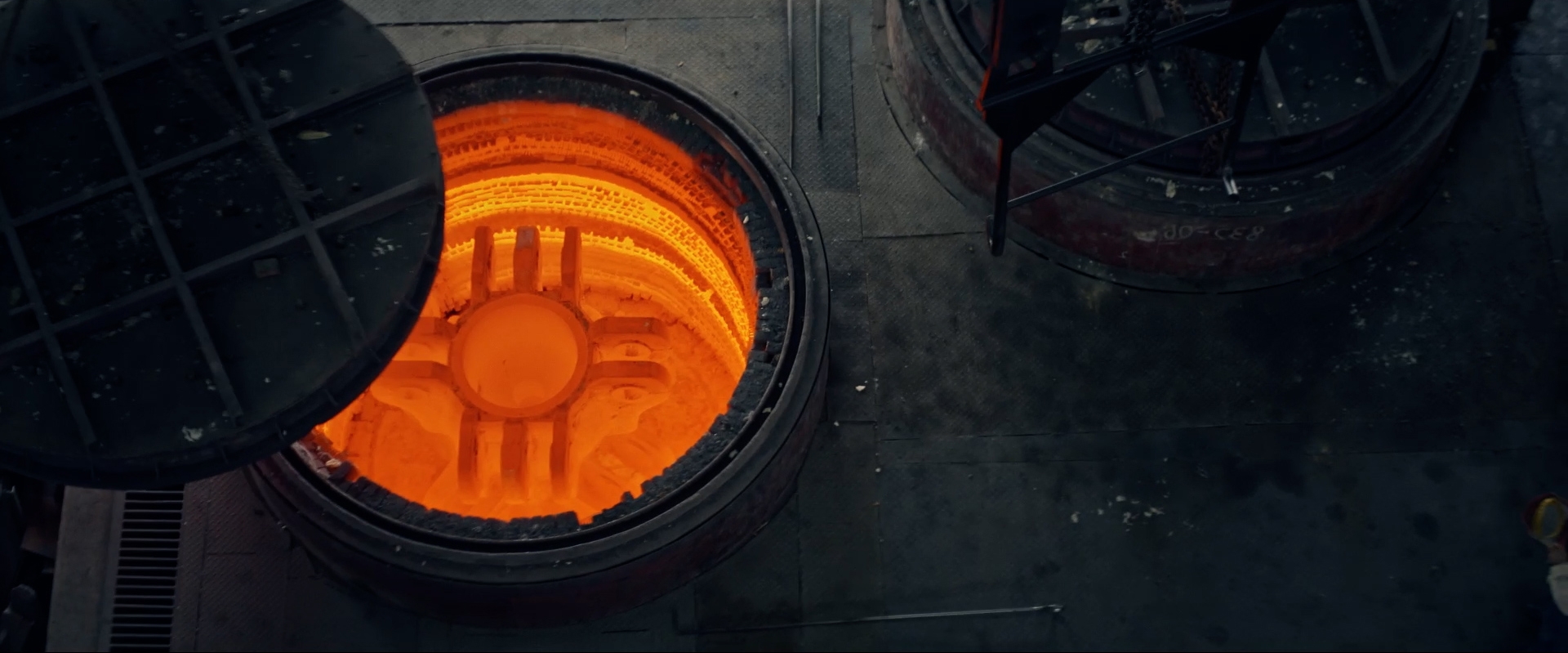

I was hypnotized by the sequence at the Chinese industrial diamond manufacturing plant, in which you show how tiny artificial diamonds are made on a mass scale, in scores of huge industrial compressors. The sequence starts with assembling the compressors, through each step of diamond production to the finished product, and ends with this super-wide, high-angle shot over the factory floor. Can you share with us some details about how this sequence was conceived?

For each place we decided to go, we spent a long time getting access. Some of them, we weren’t sure if we were going to shoot there or not. Of course, before we arrived in China, we looked at pictures of these factories and saw that we needed a drone or something similar to make a big moving shot. We don’t love using drones, but to understand how huge this factory is, it was a good decision to use a DJI Inspire 1 inside with a wide-angle lens. And then we had to get permission to set up a drone inside the building. What factory is going to say yes? We spent two years getting the authorization to get in, and we did the shoot in two days. We tried to going back on our second trip to China, but the door was closed.

Are the rhythm and composition of a scene things you find when you actually see a place in-person for the first time?

When we prepared ourselves to go to anywhere for this film, we first spent hours studying photos of these places. We also try to tech scout each location, which isn’t always possible, but for this kind of film it makes a huge difference. Before we went to India, I spent a week doing tech scouts and preparing equipment rentals, because it’s so complicated to travel there with a lot of gear. We tried to travel light — we brought our lenses and A7SII — and sourced our equipment and crew locally.

How would you describe your creative collaboration with Jason Kohn, and how has that collaboration evolved over time?

What’s important about our work together is the chemistry. I can talk to Jason about life, as well as cinema. And I love that he’s a visual director. He obsessively searches for symmetry in every composition, and he has an appreciation for good lenses. For a cinematographer, it’s a gift.