A Novel Approach to the Dune Mini-Series

Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC frames Frank Herbert’s classic science-fiction tale in the 3-perf Univisium format.

This article originally appeared in AC Feb. 2001

Unit photography by Petr Rolick, courtesy of USA Network

The production of Frank Herbert’s Dune, a six-hour miniseries that premiered as a widescreen event in December on the SciFi Channel, marked the realization of a dream for cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC, who had long wanted to film Herbert’s epic novel. In fact, Storaro was nearly hired in the mid-1970s to shoot a feature-film version that would have been directed by iconoclastic filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky (El Topo, Santa Sangre). “When I first read Dune, it really attracted me because it fit with my philosophy,” Storaro recalls. “When I met with the director of the miniseries, John Harrison, we exchanged our passion for the story.”

Harrison attests, “I’ve always seen Dune not as science-fiction but as epic adventure, and it operates on a high metaphorical plane for me. Vittorio’s work operates on that kind of metaphorical level in terms of color and light, and to me, the marriage of the two is absolutely perfect. The characters in Dune are representative of a great many elements in the human condition.”

“I knew that in making Dune, particularly for television, we had a great chance to practice cinema because we had much more time to present the story.”

— Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC

Harrison, who previously scripted Tales From the Darkside: The Movie (1990) and co-scripted Dinosaur (2000), adapted Herbert’s novel for the small screen. “I basically broke it up in my mind into three separate movies,” he explains. “The book was originally published as three separate novellas — Dune, Muad’ Dib, and The Prophet— so I used that as the paradigm for creating a miniseries. While I created an arc that went from Book One to the end of Book Three, each one had a discrete story to tell — three separate movies unified by one overarching theme.”

Herbert’s novel presents the adventures of young Paul Atreides (Alec Newman), heir to the noble Duke Leto Atreides (William Hurt) and an ancient prophecy. House Atreides is among several feuding Great Royal Houses that comprise a tenuously balanced trilogy of power, along with an emperor and the Navigators of the Spacing Guild. That balance appears to favor House Atreides when Leto is ordered by Emperor Shaddam IV (Giancarlo Giannini) to oversee the production of Spice, a life-sustaining substance that is the most precious commodity in the universe. It is believed among the houses that he who controls the Spice controls the empire.

“I wanted to shoot Dune in a traditional, classical style. I did not want to create a fast editing pace, and I did not want to use handheld cameras. I wanted to dispense with most of the contemporary cinema vocabulary.”

— writer-director John Harrison

When Leto is betrayed by one of his own, a devastating conflict ensues. Paul and his mother, Jessica (Saskia Reeves), a witch with mind-control powers, must escape into the desert. Under his mother’s tutelage, Paul hones his own, considerable mystical gifts, begins to see into the future and realizes his far-reaching ability to shape it.

Dune was produced as a feature film in 1984 under the direction of David Lynch, but Storaro says he appreciates the longer form of the current production. “I knew that in making Dune, particularly for television, we had a great chance to practice cinema because we had much more time to present the story, [as well as a decent budget]. Usually, the budget for a big TV series is not the same as a big feature film, so you usually have to deal with the [opposite situation].”

When the time came to discuss a format for the project, Storaro had a very specific goal. “Today, every electronic project is transferred to high-definition [HD], and video projects will also be [presented in] the DVD format. You therefore need much higher quality. Very soon, large HDTV sets will be around the world, and the quality of the original project should be high enough to fit the level of a big display. If a video project films just for NTSC [standards], it’s a very big mistake,” he argues.

Storaro therefore convinced Harrison and producers Richard Rubinstein and Mitchell Galin to film Dune in Univisium, a 3-perf format invented and championed by the cinematographer and his son, Fabrizio. “I was thinking about the advantages of a common standard for future television and future cinema,” Storaro says. “Widescreen television today [has an aspect ratio] of 1.79:1; French cinema is 1.66:1; American, Italian and European cinema is 1.85.1; 65mm is 2.21:1, and anamorphic is 2.35:1. It’s a jungle of numbers, and it’s unbelievable that we don’t have a uniform standard. When we have to transfer a movie with a pan-and-scan system in order to have a full-screen TV version of the film, it’s like cutting a painting to the size of the wall on which it’s going to hang.

“I believe that more and more, cinema will be seen in two different ways: HD and 65mm,” he continues. “If this is true, why aren’t we thinking today about how to combine those two formats? After it is seen in theaters, a film will be seen with a video projector and on DVD. We need a format that is the same for both situations; 65mm has an aspect ratio of 2.21:1 and HD is 1.79:1, [so I created Univisium] to strike a perfect balance of 2:1.”

Univisium, which Storaro used for the first time on Tango in 1997, is a 3-perf pulldown on film that allows for a wide image suitable for both theatrical projection and home viewing. The image area on the film negative is 12mm x 24mm, as opposed to 11.35mm x 21mm on panoramic 1.85:1 film. Storaro proposes the use of digital optical sound to preserve this large image area on the negative. “There is a lot of waste in today’s film negative,” he notes. “We’re wasting the sound area [because] we don’t use it in the negative. Very soon, there won’t even be one in the positive. There is an enormous gap between two frames in 1.85:1. With 2:1, we can use the entire negative for images and can use three perforations instead of four. We can put two frames next to each other with enough space for the splice. The negative is bigger, and because we don’t need anamorphic lenses, there is much better image quality with no distortion.”

Storaro estimates that by shooting in the Univisium format, the Dune production was able to cut costs by 25 percent down the line. “Every camera magazine saves 25 percent more time and film,” he says. “That means more creativity for the director and the actors during shooting. At an industrial level, it means 25-percent savings on processing, shipping and interpositive [expenses].”

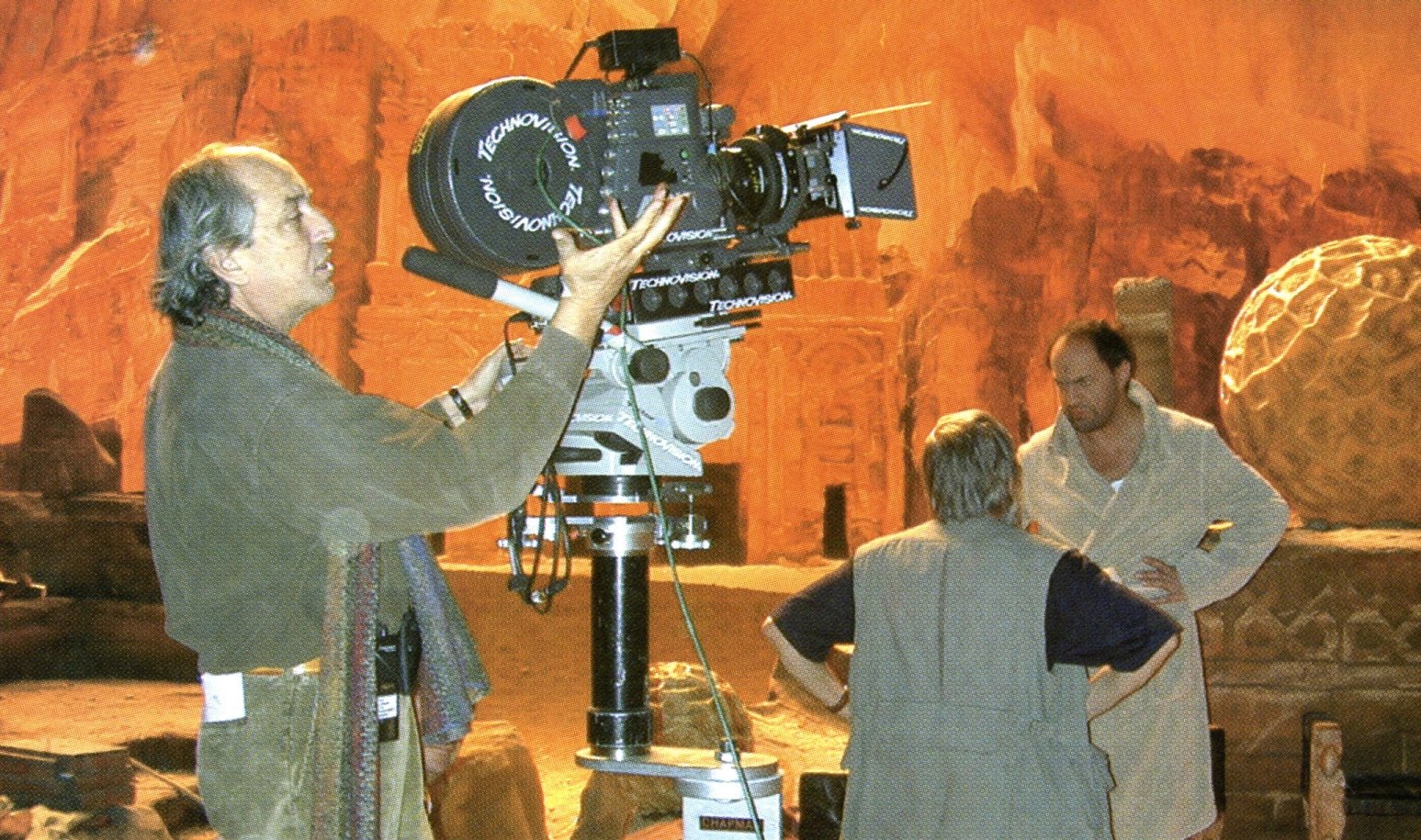

Clairmont Camera holds the rights to the system in the United States and Canada, while Italy’s Technovision holds the rights elsewhere. Both companies have adapted some Arriflex cameras for Univisium, and Technicolor has licensed the format for processing. “They’ve made all the changes necessary to print from 3-perf over to 4- perf dailies as needed,” Storaro says. In printing from 3-perf to 4-perf from interpositives to internegatives, some anamorphic squeezing of the image is necessary on a Univisium release print to keep the 2:1 ratio.”

Dune is the fifth film to be shot in the fledgling format, and the first to be shot as an original television production. For Dune, Technovision modified some Arriflex 535Bs. The camera’s lens boards was shifted to match the optical center of the film, just as with Super 35, for frill-aperture shooting. The camera’s shutter is 180 degrees at its widest opening, and Storaro filmed Dune entirely at T4.

Although he has been “in love” with Cooke Series B lenses for a long time, Storaro chose Series 4 lenses for Dune. “They’re a little too sharp, but Series 4 is the only Cooke series with a good anti-reflection coating,” he notes.

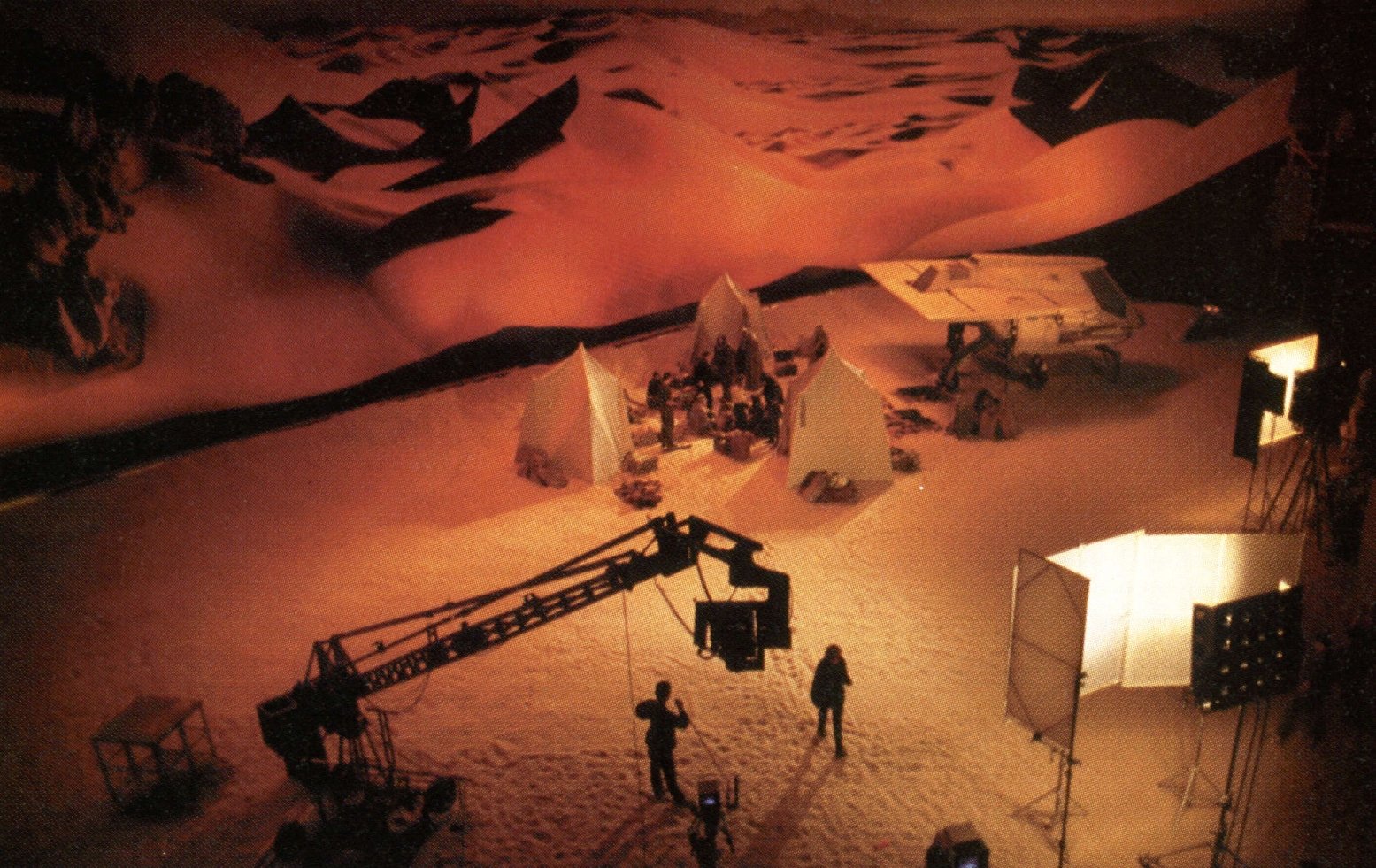

Storaro also proposed to his Dune collaborators that he use his Iride dimmer lightboard in conjunction with TransLite backdrops. “We needed a vision of another planet and the vision of a huge desert,” says Storaro. “The filmmakers were originally planning to go to Morocco, Tunisia or Algeria to use real locations. Most of the scenes in Dune are at night [and feature] two different moons. Shooting like that can be very expensive.

“Instead, I presented concepts that came from my experience of working with Carlos Saura. On Flamenco [1995], we began working with aluminum frames and a special material that was translucent; we mainly worked with light and shadows,” he notes. “The second project was Tango, on which we used color with screens. On our most recent picture together, Goya in Bordeaux [1999], we were able to print images on top of this material.

“I showed the Dune producers that we could use this TransLite material [in conjunction] with images that we could create ourselves,” Storaro continues. “My son Fabrizio and I made some samples on the computer by mixing together original photographs with transparencies of the desert. We created an entirely new vision, a new world. We could print [images] on this TransLite material and extend them to 300 feet long and 40 feet high. It created a new vision of Dune, and it helped the actors because it wasn’t just a greenscreen behind them. Every normal shot didn’t have to be a special effect, and we didn’t need to go out on location.”

Storaro notes that the savings created by this approach enabled him to bring his regular crew onto the project, “making the quality level high, but staying within the budget and schedule.”

Harrison says he was thrilled by what Storaro was able to accomplish with Translates. “My fear had been that we would have to make Dune with CG images, putting actors in an environment with which they had no connection and asking them to act without any reference,” he says. “But when I met with Vittorio and talked about these Translates, I realized that we could go into a soundstage and create magical environments for the actors, who would feel as if they were really within them.”

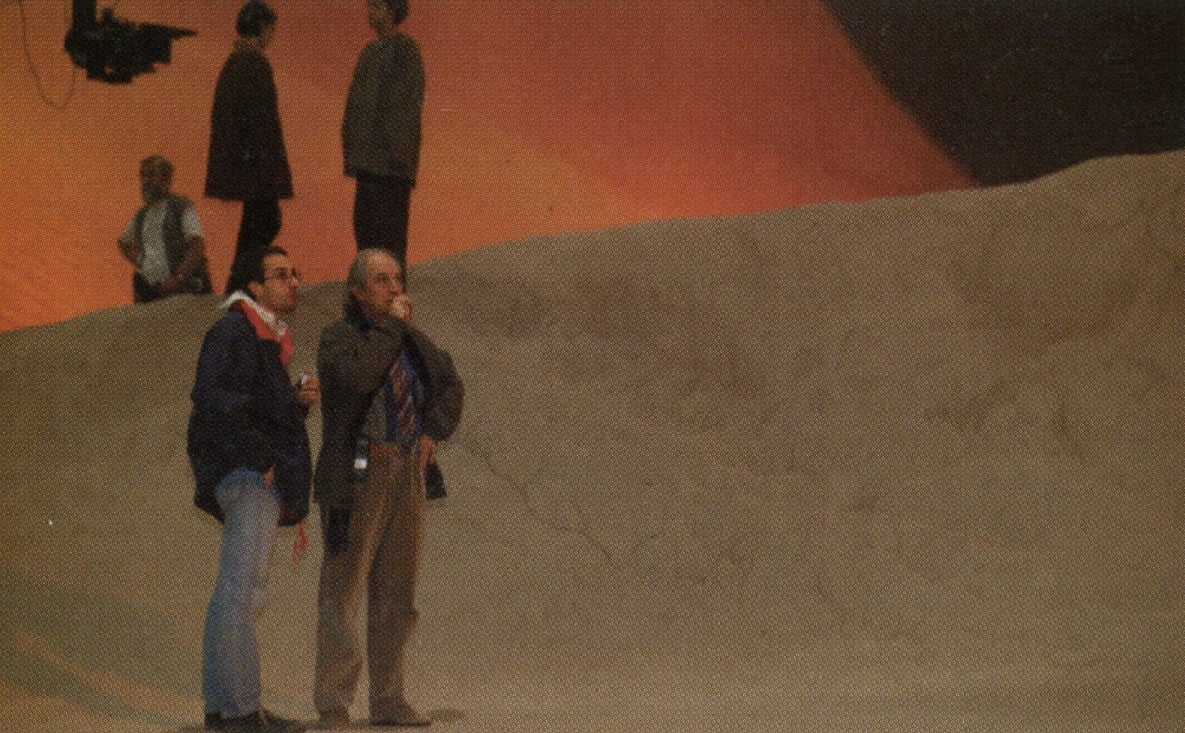

Dune was shot at Barrandov Studios in Prague, one of the largest soundstages in Europe. “Leni Riefenstahl made many movies there,” says Harrison. “It’s huge and well-equipped. The primary benefit of using the soundstage, of course, was to give Vittorio the freedom that we wouldn’t have had on location. In searching for ways to create the world of Dune, I soon realized we could [either] shoot on location and create a world that was somewhat familiar, using terrain and environments that we all had seen on film, or we could create a very stylized world like nobody had ever seen.”

The soundstage at Barrandov Studios features a large overhead grid for lights, but Storaro used it very sparingly. “I don’t usually like overhead lights; light usually doesn’t come from overhead in the real world,” the cinematographer notes. “I love floor lights or window lights. With the Iride lightboard system, everything was pre-rigged, and I was able to go through lighting changes in a very short time. That was important because we were shooting completely out of continuity.”

As with everything Storaro shoots, color was a key element in his strategy for Dune. According to Harrison, the first thing the cinematographer did after he was hired was to plot out the spiritual journey of Dune’s protagonist, Paul Atreides. “Vittorio wrote a wonderful essay, ‘The Journey of Paul Atreides from Birth to Enlightenment,’ and it is essentially a journey described in terms of color and lighting. The rest of the characters and locales in Dune are also informed by Vittorio’s sense of color and light; his cinematography is a really complex form of storytelling on its own, independent of the narrative — you see the odyssey of Paul through Vittorio’s work.”

Storaro’s treatise is what he calls his “ideation,” a symbolic map of color and emotion that he develops for every film and uses as a bible for lighting the story. He explains, “For Dune, I thought of using the metaphor of becoming mature through four different stages: childhood, youth, adulthood and maturity. So I made the metaphor of the four basic elements: earth, water, fire and air. The harmony between these elements makes the balance of perfect, elemental light. From matter, through these four basic elements, comes energy, and I think this could be a metaphor for what a life is about.

“First, Paul acquires the knowledge of his father, which is symbolized by the element of earth and the color ocher or black. The opposing family, the Harkonnen, are represented by the element of fire and the color red, which signifies conflict. The people living in the desert country, the Fremen, are represented by the element of water and the color green. The emperor of the entire universe is connected with the element of air, and is therefore seen through the metaphor of the color blue.

“Only at the end, after Paul goes through these four different experiences, these four different colors, does he become the ruler of the planet. At that point he becomes a symbol of energy, which is the unity of the four basic elements, symbolized by the color white.”

To achieve his color scheme, Storaro relied on color gels that bear his own name: Rosco’s Vittorio Storaro (VS) Collection. The development of the collection can be traced to the early 1980s, when Storaro was shooting One From the Heart for Francis Coppola. The cinematographer recalls that Rosco Cinegels were unnecessarily complicated to use at that time. “It was almost impossible to use just one normal gelatin to achieve one specific color,” he remembers. “With yellow, for example, I had to use three layers; for indigo, I was mixing magenta with blue.”

Storaro began collaborating with Rosco on the creation of a collection that would feature a single gel for a single color; the result was a new collection that encompasses the seven colors that prismatically break out of white light: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. Storaro suggested that the collection be named after Sir Isaac Newton, who is credited with discovering the array of colors, but Rosco elected to name it after Storaro instead.

The use of VS gels on Dune was another cost-effective measure. “When you use more than one layer of gels, the heat from the light destroys them, and it becomes twice as expensive to use them,” Storaro points out. “In addition to using single gels, we kept the lights from the dimmer board down until we rolled camera, so I was saving money on both the lights and the gels — it takes time to change both.”

Storaro selected Kodak Vision 200T (5274) stock for the production, noting that the emulsion “has enough sensitivity to make my work on a soundstage very comfortable. It [cuts well with] any other high-speed film, and the color and contrast will hold up.” He adds that Kodak stocks have noticeably improved since he shot Dick Tracy in 1990. “At that time, the film was not able to reproduce specific tonalities such as indigo and violet, and I met with Kodak representatives to discuss that,” he recalls. “The new negatives and positives are more selective in reading different wavelengths — you can tell the difference between blue, indigo and violet.”

Harrison notes that although Dune is set in the future, “it’s almost retro, more like Shakespeare than Heinlein or Asimov. The story is very classical — a young prince is taken from his home by his father, who is loyal to the emperor, to a world where he has no desire to go. Conspiracy is everywhere. There is fighting over the wealth of the empire, and the boy is left to die in the desert. He’s adopted by the indigenous desert people, who are seeking a messiah; he plays into their myths, becomes their hero and leads them in a successful rebellion against the empire.

“Early on, I told Vittorio I wanted to shoot Dune in a traditional, classical style,” Harrison continues. “I did not want to create a fast editing pace, and I did not want to use handheld cameras. I wanted to dispense with most of the contemporary cinema vocabulary. I wanted to go back to the classic style, which Vittorio was very happy to do.

“This meant that the lenses we wound up using were generally in the 25mm range. Rarely did we go above the 75mm focal length. There were a few instances where, for an emotional moment, we went to 200mm or 300mm, but we mainly used wider lenses.

“I wanted the camerawork to be a function of telling the story,” says Harrison. “One day, when I was worried about how we were staging a particular scene, Vittorio told me a wonderful thing. He said, ‘John, you have to pick the spot where you want the camera to be at the key moment, and back up from there. That way, the camera will be at the perfect place for the scene [when you reach] that moment.’ The camera moves in Dune were all designed to get to that moment.”

One of the unusual visual touches in Dune is the use of ultraviolet contact lenses and black light to convey the deep-blue eyes of the Fremen. UV “spill” in some of the shots had to be cleaned up in post-production, and Lou Levinson, a colorist at PostLogic who has worked with Storaro for a dozen years, handled the chores with Storaro sitting alongside. The final 3-perf film was recorded to high-definition 24p at 1080. A 1080i color-corrected master was made and used to create masters on DigiBeta, D2 and D3 at both standard definition and HD digital-component formats. The color-corrected 1080i can be taken over to PAL, NTSC or another HDcam tape.

“Vittorio is used to pushing the boundaries of what film can do,” says Levinson. “I’m grateful I’ve had a chance to work with him for 12 years — he keeps me on my toes.”

For more on other Dune projects: