October Issue of AC Arriving Soon

Features coverage on a diverse projects including Wonderstruck, It, Manhunt: Unabomber and Outlander.

The new issue of American Cinematographer magazine features coverage on a diverse array of projects including Wonderstruck, It, Manhunt: Unabomber and Outlander.

Here are some highlights from the coverage inside:

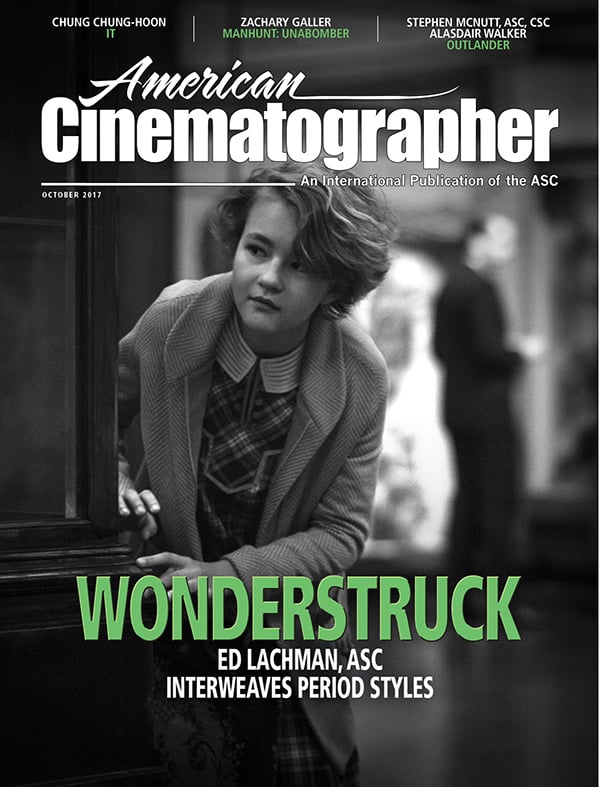

Wonderstruck

A deaf protagonist and a story set in two time periods were just two of the challenges for director Todd Haynes and Edward Lachman, ASC — who co-authored the issue’s cover story on this innovative drama:

Based on Brian Selznick’s partially illustrated youth-oriented novel of the same name, Wonderstruck masterfully interweaves the stories of two 12-year-olds in two separate cinematic languages and time periods: Ben (Oakes Fegley) in 1977 and Rose (Millicent Simmonds) in 1927. Rose was born deaf, and Ben becomes deaf following an accident. Both children run away to New York City, tracing the clues within their personal histories to find what they’re missing and longing for in their lives — for Rose, her estranged mother (Julianne Moore), and for Ben, the father he’s never known.

“Deaf culture is a visual culture,” says Selznick, who also authored the film’s screenplay. “Even their language is visual. That got me thinking about how I would approach Rose’s story with the drawings in my book. I wanted to tell the story of a deaf character through the ‘silence’ of black-and-white drawings, as they parallel her point of view.” This approach would also use the silent period of 1920s cinema as a metaphor for her world. Selznick added, “Reading Wonderstruck and getting her story only through pictures would make the readers feel like they were Rose, herself. This idea excited me. The other story, the one in words, about Ben in the Seventies, would be about a hearing boy who becomes deaf. And so, by going back and forth we’d be able to have each story parallel and illuminate the other.”

Best known for his book The Invention of Hugo Cabret — which director Martin Scorsese translated to the screen as Hugo, working with cinematographer Robert Richardson, ASC (AC Dec. ’11) — Selznick here again imbues the story with the language of cinema history while turning his attentions to the collective memory of curating and museums.

For Wonderstruck, director Todd Haynes reteamed with me, continuing our collaboration, which started with Far From Heaven (AC Dec. ’02), and continued with I’m Not There (AC Nov. ’07), Mildred Pierce (AC April ’11) and Carol (AC Nov. ’15). Haynes describes Selznick’s story as an “intensely cinematic” idea that takes the form of a mystery — accumulating clues, answering questions and posing new ones — all while leading to final discoveries. “The film is structured as a dual narrative with the two stories paralleling each other and driving the mystery of the film alongside the answers each central character is seeking,” the director says. “Why are these two stories, set 50 years apart, being paired? What is their connection? Why do they interweave in these ways? We observe the events of the two characters’ journeys mirrored in their deafness — fleeing their homes for New York City and ending up at the [American] Museum of Natural History.”

Indeed, the way the two stories interconnect through two different time periods creates the mystery at the core of the story. When you’re watching it, you’re asking, “Why are these two stories sharing one movie?” All the relevant questions come out of that uncertainty.

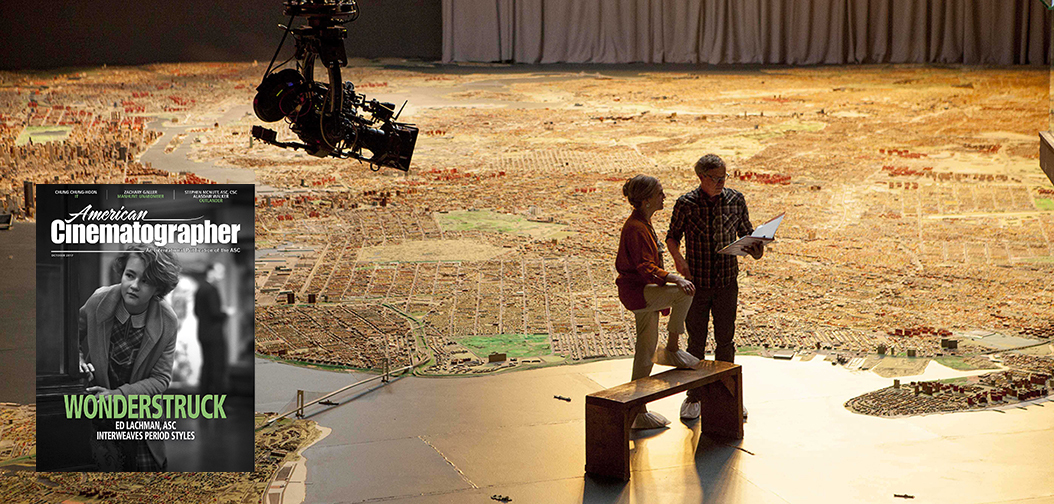

Todd’s film is also a tribute to what language is and what you can do with your hands: the sign language; Rose’s paper cutout-and-glued miniature buildings; the handmade live-action miniatures that give form to Ben’s imagination; and the scenes at the Queens Museum, with its handcrafted Panorama of the City of New York.

The cinematography presents each story with a look that evokes the cinema of its period, with 1927 depicted in the black-and-white of silent-era cinema, and 1977 in the chroma of 1970s urban street realism. We worked with 35mm Kodak motion-picture negative — black-and-white Double-X negative for the ’20s, and two Vision3 color stocks for the ’70s — shooting primarily in 3-perf with Arricam Studio cameras; for one key location, we opted to shoot digitally. Through editing, sound and music, our two stories coalesce as one.

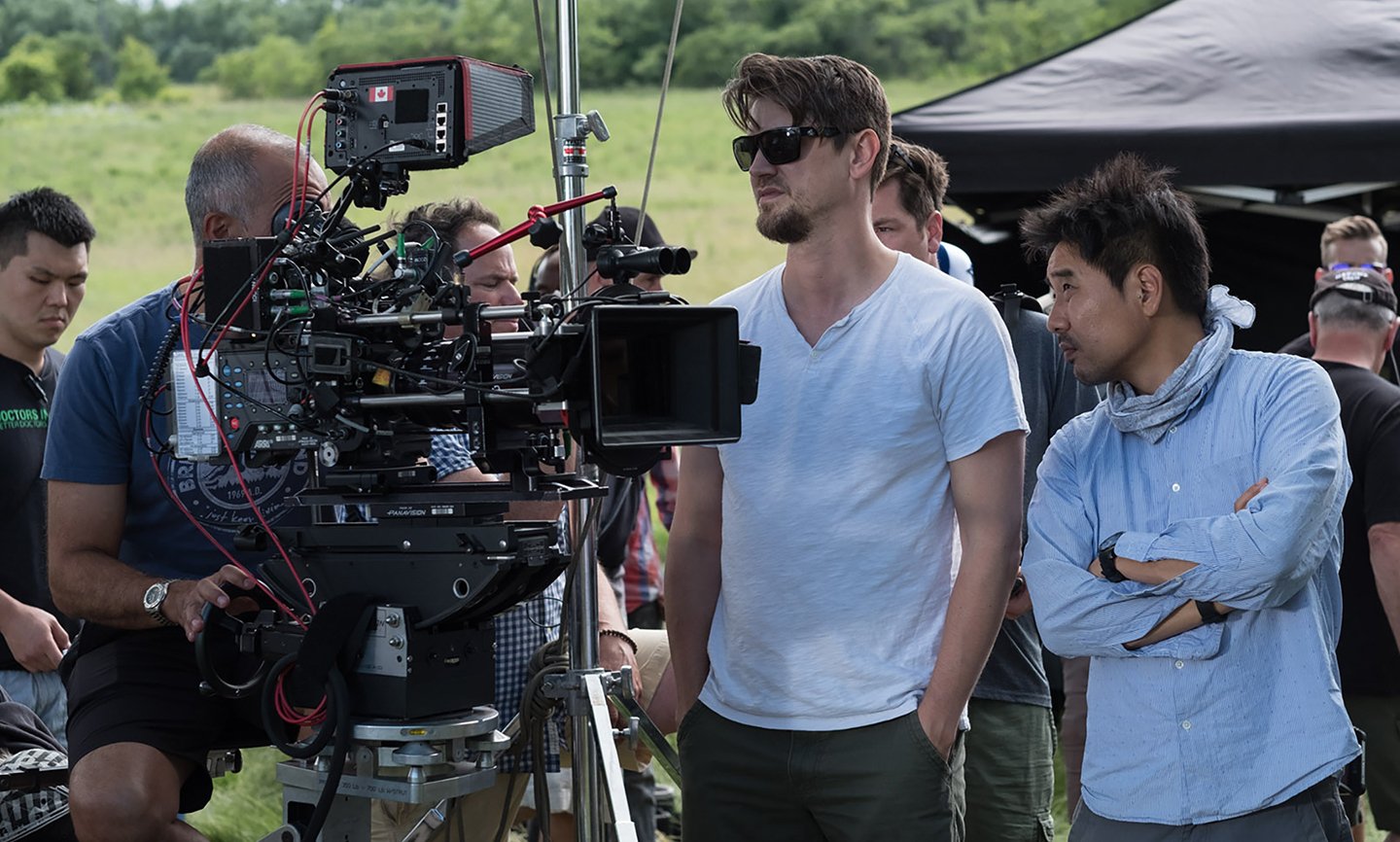

It

AC visits the Toronto set of the boxoffice hit, where director of photography Chung Chung-hoon and director Andrés Muschietti mined the horror of Stephen King’s 1986 novel:

“Whatever [Chung] contributed would make what I had better,” [director] Muschietti recalls. “Our discussions were about temperature. I wanted a hot summer with everyone sweating all the time. I love characters with shine on their faces. We also discussed the balance of making something realistic, but with that element of intrigue — that something is not right.”

Chung mulled over the notion of a period look, but ultimately the 1980s feel is conveyed chiefly through production designer Claude Paré’s sets and the work of costume designer Janie Bryant. “Trying to make a movie set in the 1980s look like the 1980s can be dangerous,” the cinematographer says. “At first, I thought about shooting with 1980s lighting rules and gear. But we didn’t, and in the end it didn’t matter. We’re just trying to capture a natural look.”

Finding mainstream 1980s lighting too artificial, Muschietti preferred to light through windows and bounce off the floor. “I wanted to convey intimacy with the characters,” he says. “I love backlights and soft lights that are unsettling.”

That jibed well with Chung, who notes that his experience with Stoker taught him how to light quickly using one source. “I feel lucky,” he says, “because some directors will always say, ‘Can you make more light?’ But this movie is very naturalistic. My responsibility is to the audience and to tell the story, and if you want this movie to scare people, a natural look is best.”

Manhunt: Unabomber

Cinematographer Zachary Galler and his collaborators offer AC a firsthand look at the making of this procedural series:

Behind the camera, television veteran Greg Yaitanes was in the director’s chair for all eight episodes, and he teamed with up-and-coming New York-based cinematographer Zachary Galler for the length of the show. After six weeks of prep, principal photography began in early February 2017 and continued for 78 shooting days. Close to the end of production in late-April, Discovery invited AC to visit the set in Atlanta.

The day’s shoot has already begun when AC touches down at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. The first stop is Manhunt production HQ, a former wagon factory on the outskirts of town, for a look at the show’s “idea room” — a glassed-in conference room that better resembles a detective’s office than a television production’s. “It’s a distillation of all our ideas,” Galler later remarks. “The references in that room came from the look books that Greg, production designer Erik Carlson and I put together while the show was gearing up.”

Galler credits the room as a visual aid that’s helped to streamline collaboration across the show’s creative team, from prep to post. Its walls are plastered with photos, notes, printouts, charts, diagrams and drawings that, from a distance, establish a definite texture; the images don’t really begin to make sense, though, until you get up close and examine the details. Yaitanes describes the accumulation of these details as “a procedural approach to the police procedural.”

Outlander

Cinematographers Alasdair Walker and Stephen McNutt, ASC, CSC capture the ever-changing eras and locations of Starz’ romantic time-travel series:

“Season 3 begins with the main battle sequence in the Outlander series, and the final encounter between the hero Jamie and the villain Captain Jack Randall,” explains cinematographer Alasdair Walker. “Director Brendan Maher and I, along with the writers, wanted to approach the battle sequence in a way that was different from what is shown on other shows, like Game of Thrones. We wanted an extensive sequence that is part dream sequence and part action sequence, so we worked it out as a series of flashbacks.”

Committed to an authentic portrayal of the battle, the production performed extensive research with assistance from the University of Glasgow archaeology department. It is known that with their broadswords in hand, the Highlanders charged the government regiments, a tactic that had worked to their advantage in previous encounters. To capture this suicidal charge into cannon and musket fire, Walker employed multiple cameras — predominantly Sony PMW-F55 CineAltas, the production’s primary units, fitted with Cooke S4 Primes and Arri/Fujinon Alura 18-80mm and 45-250mm zooms (both T2.6) — shooting in 2K and 4K simultaneously, and recording to SxS Pro+ memory cards and Sony AXS-R5 external 4K raw recorders, for each respective resolution. Multiple handheld and Steadicam rigs, as well as tracking vehicles fitted with Technocranes, also serviced the sequence.

Supplementing the F55s were Sony a7S cameras — fitted with Sony FE 16-35mm GM (F2.8) zooms and shooting 4K to SanDisk Extreme Pro SD cards — that were buried in armored boxes, enabling the Highlanders to trample over them during the action, as well as GoPro Hero4s, which were mounted to the soldiers’ shields.

The real-life battle took place in late winter, with sleet and snow falling during the bloodshed, while the event’s onscreen re-creation was shot in mid-August with an unusual amount of sunny weather. To simulate the cold, overcast feel for the start of the battle, the special-effects department added large amounts of smoke to create a foggy atmosphere that also diffused the sunlight.

Portions of this issue will be posted on the AC site after Oct 1.

You can subscribe to the digital and print editions of AC here.