One on One: ASC Vision Mentorship Program

For decades, ASC members have informally volunteered to help emerging cinematographers — the decision to create an official mentorship program, however, is barely a year old.

By Peter Tonguette

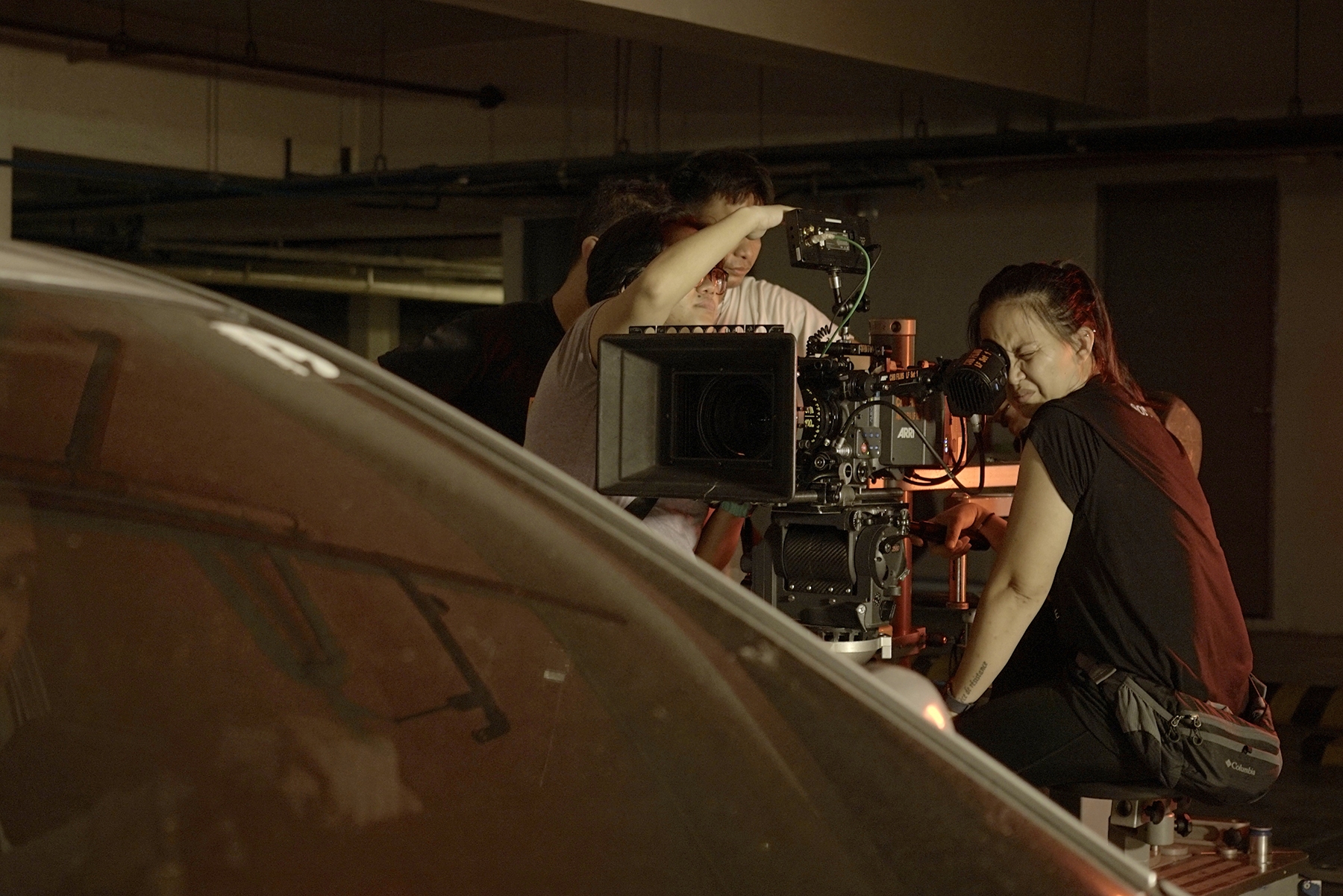

Not long ago, up-and-coming cinematographer Tey Clamor was thinking about the best way to embark on a new motion-picture project. She lives in the Philippines, but she had the chance to pose some questions on the topic to a veteran Hollywood cinematographer with more than three decades of experience — and she had his undivided attention.

Last fall, Charlie Lieberman, ASC began serving as Clamor’s long-distance mentor. Communicating via email, and undaunted by the 15-hour time difference separating them, the two were paired as part of the ASC Vision Mentorship Program, an ambitious new initiative from the ASC Vision Committee and the first program of its kind for the Society. Matching promising young cinematographers with experienced cinematographers, the program seeks to tap the well of knowledge within the ASC’s ranks to help the next generation.

“We want to connect people who are very talented, who have been out of school and working in the industry for five or so years, and who are either having trouble making the leap to the next level or just trying to stretch themselves a little bit,” says Patti Lee, ASC — a co-chair of the ASC Vision Committee’s Mentorship Subcommittee. “We want to make sure the ability to succeed in cinematography is open to all.”

So what sort of advice did Lieberman give Clamor? “He told me he reads the script three times,” Clamor recalls. “The first reading is to sense whether he likes the story, characters and dramatic intent. The second read is to start absorbing the mood, tempo and styles. In the third reading, he begins to look for visual ideas that he would like to suggest to the director.”

Lieberman is modest in describing the words of wisdom he gave to Clamor. “There’s no rule on how to read a script,” Lieberman says. “We can only talk about our own personal viewpoint and how we’ve worked in our careers.” Clamor, though, says she is grateful for that piece of advice and for her ongoing dialogue with Lieberman. “These kinds of opportunities are a step forward in advancing my knowledge,” she says. “Having a teacher with a different background and a solid foundation helps me get better equipped as a DP.”

There was another perk as well: At Lieberman’s suggestion, Clamor applied for and received an ASC Master Class Vision Scholarship.

A call for mentors and mentees

Mentorship, of course, is nothing new at the ASC. For decades, members have informally volunteered to help emerging cinematographers improve their skills and chart their careers. “This is something that’s been a priority for the ASC for a long time,” Lee says. “It’s something that the members are very much behind.”

The decision to create an official mentorship program, however, is barely a year old. Conceived by ASC members and founding Vision Committee chairs Cynthia Pusheck and John Simmons, the Subcommittee invited applications from potential mentees in June and July of 2019. Final selections were made, and the program kicked off in September of that year. “When Cynthia and Johnny tagged Patti Lee and me to co-chair the mentorship program, it was an ambitious schedule to try and get it up and running,” says Todd A. Dos Reis, ASC.

The Subcommittee started with a list of ASC members who had previously volunteered to serve as mentors. After this, Lee says, “We ended up putting out another call to the membership, saying, ‘We’re starting this program. If you are interested, please let us know and sign up.’ We got a pretty heavy response — much more than I expected.”

No less enthusiastic was the response of would-be mentees. More than 200 cinematographers submitted personal statements, résumés and, of course, reels of their work. “We had a couple of committees of people do some pre-vetting,” recalls Lee. “It’s kind of like a film festival, where you narrow down the field and then make your selection. In the end, we paired 73 mentors/mentees.”

In forming the inaugural roster of mentees, the ASC was on the lookout for a unique set of qualifications — namely, cinematographers who had made careers for themselves but did not yet have a foothold in the business, as well as those who clearly possessed talent but whose gifts could be further honed. “We took a look at the whole package and their body of work,” says Lee, “and we tried to find the people who could benefit the most [from mentorship] but who were also far enough along.”

A global reach

Although the mentorship program is open to all cinematographers who meet the requirements, the Vision Committee hopes the program will promote inclusivity. The final mix of mentees is a remarkably diverse bunch, including cinematographers from around the globe. “The ASC is an international organization, and having mentees that are not from Los Angeles, New York or anywhere else in the U.S. should not faze us,” Dos Reis says. “We are willing and honored to share our knowledge with people from around the world. Cinematography is a global art; it has no borders.”

The mentorship program specifies two in-person meetings between mentors and mentees, but for mentees based outside of the U.S., email, Skype and telephone calls are encouraged. Lieberman did not find it an impediment corresponding with Clamor via email. “The largest group of people I mentor comes out of the [ASC] Master Class, and although I meet them in person, that eventually turns into email exchanges,” Lieberman says. “I think all those forms of communication are just fine. We’re used to them now.”

And, as Clamor sees it, it’s the quality of the mentorship that matters, not where and how it takes place. “I’ve always believed in the value of mentorship and learning,” she says. “I was taught by some of the greatest DPs in the Philippines, and having an ASC member teach me is a dream.”

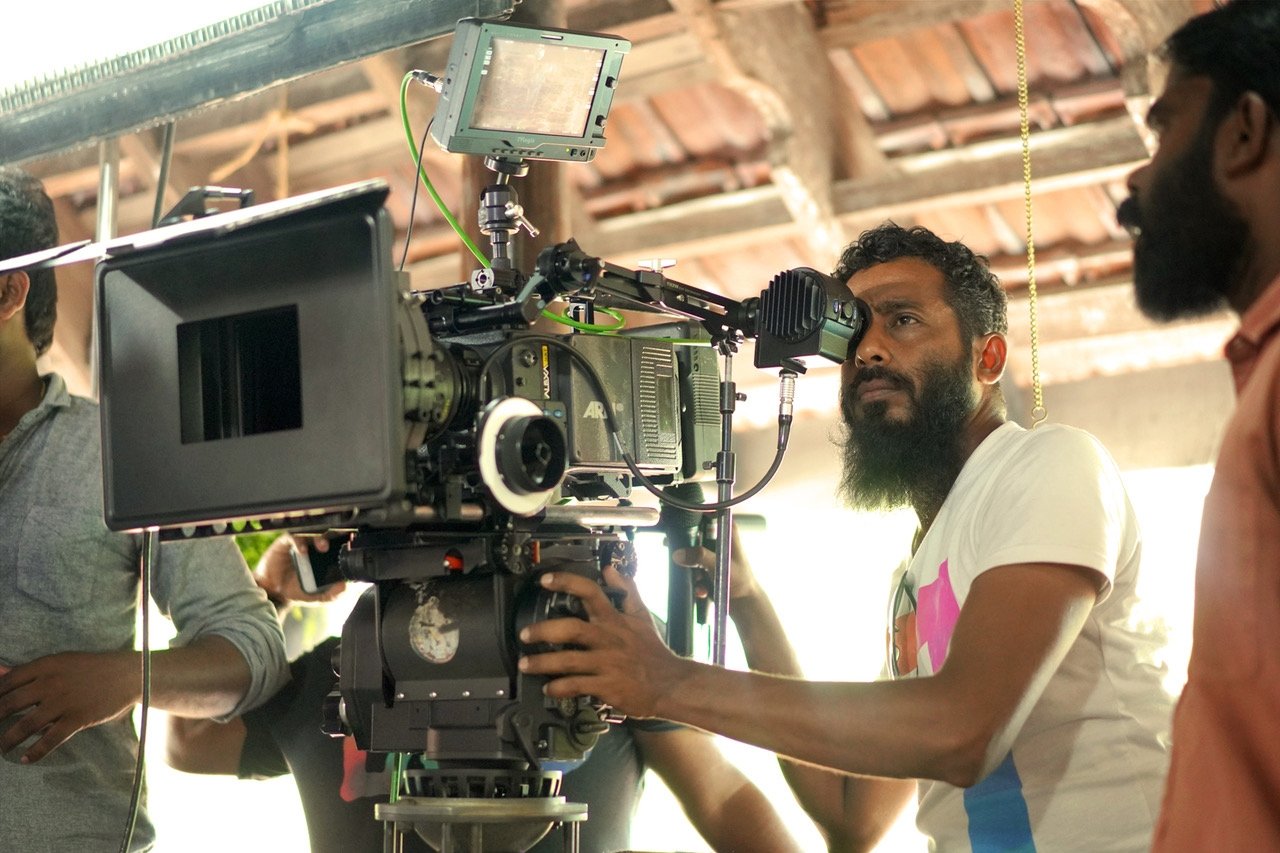

India-based cinematographer Prakash Velayudhan, another mentee, learned about the mentorship program from the ASC website and immediately recognized it as a way to boost his career. “I always wanted to study cinematography at a film school, but [due to my financial situation] I started assisting and learning on my own,” Velayudhan says. “This mentorship program is a perfect [way] for me to advance in my career, become an even better DP, [and] get [more] technical knowledge.”

After he was chosen for the program, Velayudhan was paired with Mark Irwin, ASC, CSC. They first spoke on the phone and then began an intensive email correspondence. “I ask Mark for technical and creative input, career advice, how to manage producers and directors, how to collaborate with crew — actually, my questions [are about] all aspects of my career,” Velayudhan says. Fortunately for the mentee, Irwin is an open book when it comes to tips, suggestions and hard-won guidance. “Mark is always inspiring me to ask questions,” says Velayudhan.

Irwin says, “Prakash had questions [that had been agonizing him about his career], about how to deal with producers, how to converse with the director on a [meaningful] level. In many ways, I look at this as tech support on a creative level — creative support.”

In fact, Irwin found mentoring Velayudhan through virtual means was more fulfilling than an in-person encounter. “You can get into a huge amount of detail in an email,” Irwin says. “The latest one was yesterday; he asked about split-field diopters, and I copied and pasted all these images of shots that other people had done, including what I had done on Scream, and said, ‘This is what to look for, and this is what to look out for.’”

The exchanges have paid off. When a filmmaker friend asked Velayudhan for some guidance in lighting a low-budget, self-financed feature, Velayudhan recalled some photos Irwin had shared with him. “I was getting location stills of Mark’s lighting setups [where] he used some custom-made lights, China balls and practical bulbs for some sequences,” says Velayudhan, who used a similar approach on his friend’s film. “In this feature film, I did not use any film lights. That was a great help for the production and also a big achievement for myself — only because of Mark.”

The mentee adds: “I feel like I have a great master guru to guide me in my career!”

Representation a priority

The participants in the mentorship program are not only varied in their geographical locations but also diverse in their personal backgrounds. As a transgender woman, cinematographer and mentee Ava Benjamin Shorr must navigate sets that are not always accommodating. “When you’re trans, you are going through a lot of things that bodily don’t make you as equipped as a [cisgender] dude who’s just walking through the world of being on set,” she says. “When you transition, you lose muscle mass; I’ve had a couple transition-related surgeries that have put me out of work for months at a time.”

Just before applying for the mentorship program, Shorr went through a particularly tough shoot on a low-budget feature. “It was a really, really hard job for me,” she says. “I felt that between the producers and the production and sort of the toxicity of that environment, I was looking for a mentor or someone who could help me navigate some of the trials that would be coming up in my career.”

After being accepted into the program, Shorr was paired with Rachel Morrison, ASC. In addition to meeting over coffee, mentor and mentee have traded text messages. “Rachel is just so generous with her thoughts and her energy,” says Shorr. Noting that Morrison shot a feature while pregnant, Shorr adds, “Things like that give me the permission to be myself and to own who I am.”

For Morrison, the experience was a way of providing another cinematographer with the sort of support she lacked early in her career. “I felt like I always had to learn by doing,” Morrison says. “Every set that I was on, as they got bigger, was the biggest set I’d ever been on because I had never really been mentored by anyone. Now that I’m in a position to help, my hope is that it would make it one step easier for Ava.”

In the end, Morrison was so impressed with Shorr’s talent and energy that she helped her secure an agent and recommended her for an HBO series, Equal. Shorr got the job, and at press time, she had shot three episodes of the show.

“There are people you hesitate to recommend because you feel like the skill might be there, but their personality isn’t always a good fit,” Morrison notes. “And then there are people you take real pleasure in recommending because you know they’ll knock it out of the park — Ava was one of those people.”

Representing real life

Many participants bonded during the course of the program, but few mentors and mentees are likely to have been paired as fortuitously as Simmons and cinematographer and mentee Melinda James. “She came to one of my photo exhibits years ago,” says Simmons, who also shows his work as a still photographer. “All of a sudden, through a random process, she became my mentee. She’s a wonderful cinematographer.”

The twist of fate was a welcome one for James, who first worked as an editor at GoPro before a gig at the music-streaming company Pandora led her to begin photographing in-house videos. “I didn’t go the traditional film-school route, and everything I knew early on was self-taught,” says James, who eventually took a 16-week introductory-filmmaking class, went to graduate school for a degree in social documentation, and is now accumulating an impressive list of commercial, music-video and short-subject credits.

After learning about the mentorship program, James applied. She had heard about Simmons’ generosity as a mentor from cinematographer friends, but the thought never occurred to her that if she were accepted, she would be paired with him. “I was so happy when I learned he would be my mentor because that’s what I had wanted ever since I’d met him,” she says. She soon discovered just how generous her new mentor is: While shooting the Netflix series The Expanding Universe of Ashley Garcia, Simmons invited James to the set to watch him work. “I got to see the process from script breakdowns to rehearsing and blocking, to lighting, to filming an actual episode — and then even all the way to post and coloring at Technicolor,” James says. “It was invaluable.”

Beyond the technical knowhow, James noticed something else: Simmons had assembled a crew as diverse as the world around him. Simmons notes, “It looks like where we should be, and because I’m a cinematographer and I’m in charge of the grip crew, the electrical crew and the camera crew, I can put people in there that represent the world.”

The experience left James determined to go the extra mile to ensure representation in her own crews. “I’ve always tried to be as inclusive as possible when assembling departments,” she says. “It can be challenging to not only find the right individuals for the job, but also take into consideration race, gender, perspective and experience. Johnny has done it, which demonstrates that it’s possible.”

Simmons sees mentoring as less a discussion about lenses or lights and more about serving as a role model. “We can talk about the technical stuff, we can talk about the art and craft of cinematography, but we also have to talk about navigating our career as minorities in this industry — that’s important,” he says. “We’re trying to make it so that when they see a Melinda behind the camera, it’s not unusual.”

James’ experience with the Mentorship Program left her inspired about the possibilities of her profession. “You can watch all the movies, attend all the lectures and read all the books you want,” she reflects, “but being in the same space as someone like Johnny, who’s been doing it for decades, and watching him work and make certain decisions is very special. I’m incredibly fortunate.”

Following the publication of this article in AC magazine, ASC members Polly Morgan and Fernando Argüelles were appointed as the new chairs of the ASC Vision Committee.

Announcements regarding applications for the next ASC Vision Mentorship Program opportunity will made on the Society's website.