Onward: Quest for Magic

Directors of photography Sharon Calahan, ASC and Adam Habib frame a fantastical adventure in the virtual world.

Directors of photography Sharon Calahan, ASC and Adam Habib frame a fantastical adventure in the virtual world.

Behind-the-scenes photos by Deborah Coleman, Adam Habib, Patrick Lin and Gairo Cuevas. All images courtesy of Disney/Pixar.

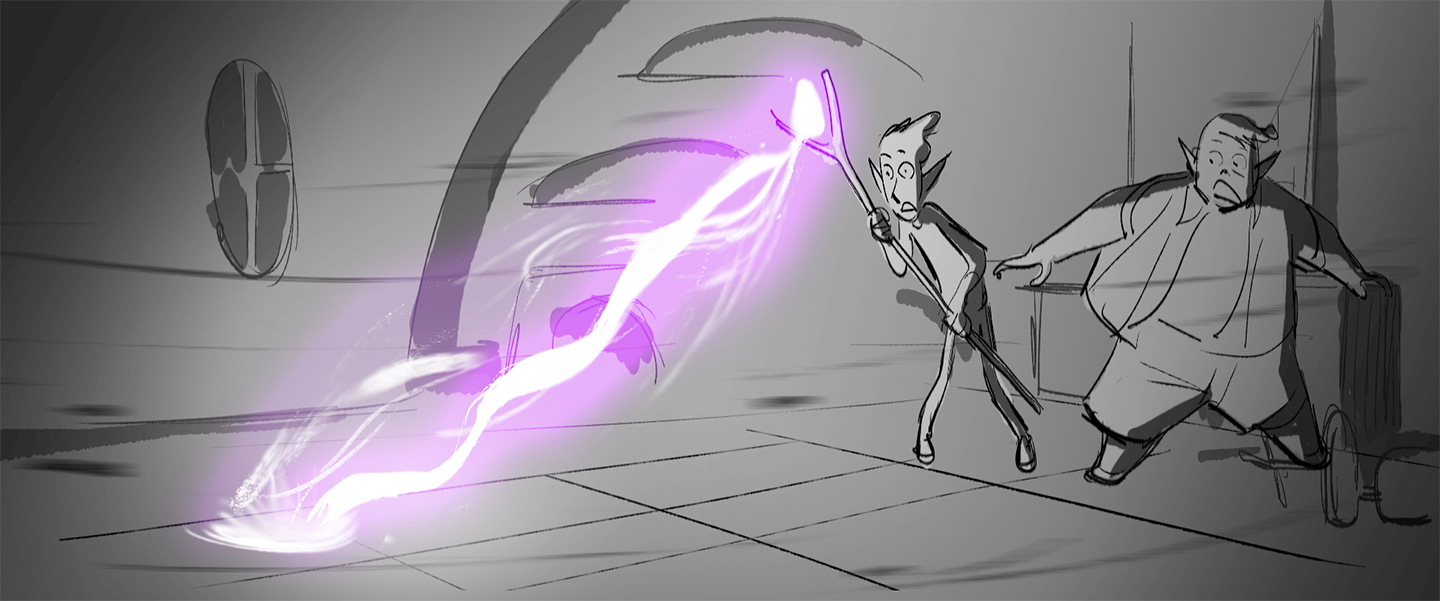

The latest adventure from the creative minds at Pixar Animation Studios is Onward, the tale of two teenage elf brothers, Ian and Barley, who embark on an adventure in an attempt to reconnect with their late father. The brothers’ suburban world is a fantastic one, populated by sprites, satyrs, cyclopes, centaurs, gnomes and trolls, but the magic of the realm has slowly faded away over many years. On his 16th birthday, Ian’s mother gives him a gift his father intended him to have: a letter detailing a spell that will enable his sons to see him one last time after they’ve grown up, along with a magical staff and gem. The brothers perform the magic, but the spell goes awry, enabling them to conjure only their father’s legs and feet. In the process, the gem is destroyed. Now the brothers have just 24 hours to find another magical gem and conjure the rest of their father.

“Onward was inspired by my relationship with my brother and our connection to our dad, who passed away when I was about a year old,” says director Dan Scanlon in a press statement. “My dad has always been a mystery to us. A family member once sent us a tape recording of him saying just two words: ‘hello’ and ‘goodbye.’ Two words, but to my brother and me, it was magic. That was the jumping-off point for this story. We’ve all lost someone, and if we could spend one more day with them, what an exciting opportunity that would be.”

Helping Scanlon bring Onward to the screen were Sharon Calahan, ASC, director of photography: lighting, and Adam Habib, director of photography: camera.

Calahan, the first animation cinematographer to become an ASC member, has been with Pixar since 1994. She was a lighting supervisor on the company’s first feature, Toy Story, and the director of photography on A Bug’s Life, Toy Story 2, The Good Dinosaur, Cars 2, and on the Academy Award-winning features Ratatouille and Finding Nemo. She originally studied graphic design, illustration and photography and began her career in the industry as an art director for broadcast television and video production. Following those jobs, she was a lighting director at Pacific Data Images for commercials and television. Calahan is currently a member of the cinematography branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Habib, who received an M.F.A. in film from the University of Southern California, started with Pixar as a camera and staging artist in 2010 and became the lead artist on Inside Out. He was the director of photography: camera on the short Lou. Onward is his first feature as a director of photography at Pixar.

Calahan and Habib spoke with AC about their work on their latest collaboration.

American Cinematographer: I’m curious about your working relationship and how the director-of-photography responsibilities are divvied up.

Sharon Calahan, ASC: Having separate cinematography departments, which are known as layout and lighting, is a historical structure originally adopted from the cel-animation world. Many people on Toy Story came from cel animation at Disney, so we adopted how they approached [the responsibilities of] movies. Over time it’s been challenging to merge them because there are tools that tend to keep them separate; our lighting tools are built on a different software platform than our layout tools. Adam is in charge of the staging and the composition of each scene, making choices about lenses, camera movement and shot choice, and working closely with editorial and the story teams. He also collaborates with the set-design team on previs to make sure all the action can be staged within each environment. I am there also, trying not to get in the way, to get an idea of their plan because I’ll be providing the lighting for the sequences — and often, we are pre-lighting so we can tell where the shadows will fall and just have a general sense of the world [in regard to] the major light sources. I tend to focus more on the overall lighting look of the film all the way through from concept art and creating our colorscript to lighting design and the final grading, which we do on Digital Vision’s Nucoda system.

It’s fascinating to think that something completely fabricated still requires a color-grading session. I mean, you’re not dealing with mismatched lighting fixtures, changing times of day, or differences in lens color bias.

Calahan: Yeah, but it’s tricky when you have 30 to 60 artists lighting a film and it has to look like a unified vision. It can be hard to keep the continuity tight enough throughout. So in the color-grading session, where I work with our amazing colorist, Mark Dinicola, I’m there to even things out. In Onward, the main characters have blue skin, and it was really difficult to keep it from going too green, gray or purple in colored-light situations. The director was particularly sensitive to that, so I spent a fair bit of time in the grade using masks for the skin, trying to even that out. And even for us, there are times when light fixtures are the wrong color!

Couldn’t you just alter the skin tone for those shots so that it stayed blue in the lighting?

Calahan: Sometimes we could do more of that, but when you have 30 artists who are all lighting different sequences, that can cause more problems than it solves. If one person were executing all the lighting, we could probably be more consistent, but under the circumstances, that would have caused a lot more inconsistencies than solutions.

Adam Habib: In terms of my collaboration with Sharon, one thing we did early on was to meet a lot, share references and talk. More than coming to any one vision of the film, I think it was just a great way of learning each other’s visual taste and what sorts of stuff we respond to. Once the movie got into full swing, we’d just see each other in the halls, running from one meeting to the next, but we had that common framework to go on.

Calahan: I think another reason [the job responsibilities] have tended to stay separate over the years is that besides the tools, we each have pretty big crews we’re supervising, and everything’s happening at once. We are probably lighting 10 different sets and about 150 shots in any given week. There’s a lot of content to look at and a lot of iterations that have to happen. It would be overwhelming to try to figure out how to do all of that and the layout/camera work at the same time. So it’s nice to have a partner; we can share and collaborate and divide and conquer.

In those early meetings and discussions, how did you both work with Dan Scanlon to establish the look of the movie?

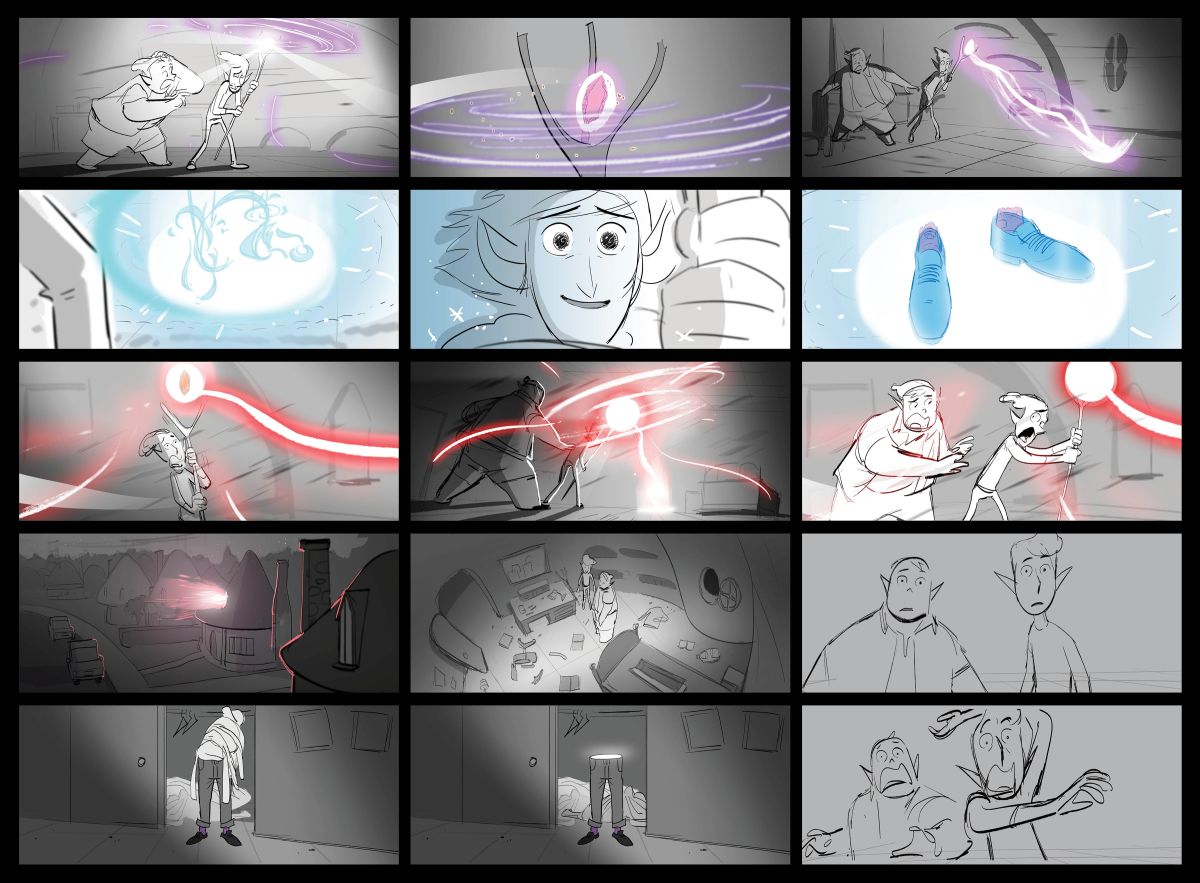

Calahan: Typically, we spend a lot of time gathering film references, still-photo references, illustrations and paintings; we create a lot of concept art, and we watch films together and are constantly pitching ideas to see what sticks. We develop a camera plan and a lighting plan, but those continue to evolve as the show goes on.

We don’t do it very often because it’s hard to schedule and can be expensive, but every now and then I’ll set up a lighting workshop where we bring in somebody to do a hands-on, real-world lighting demo. Bill Bennett [ASC] did a car-lighting workshop for us just before Cars 3 started up, and then we discussed what we could learn from that. It’s both educational and inspirational to see that.

Onward was inspired by the look of Cooke /i anamorphic lenses. How did you come to that decision?

Habib: Early on, we were talking about fantasy as a genre, and we noted that all the movies we were referencing, all these great films from the ’80s like Labyrinth, The Goonies and The Dark Crystal, were all anamorphic movies. Dan Scanlon was a little skeptical about the idea, so we brought in an [Arri] Alexa Mini and Cooke anamorphic lenses and shot a test for him. He kind of perked up and said, ‘Oh, I like it. I like the texture this adds to the background.’ And of course, Sharon and her team came in and helped to make that look possible. But the way the anamorphic lens renders the world was something we all liked; we liked the way it called back to those earlier fantasy films, and how the unique texture gives permission for magical things to happen. In Camera and Staging, we determined the degree and character of distortion for each lens in the anamorphic set. So, for example, the look of the 50mm is unique from that of the 35mm. We decided to create a contrasting look for scenes of the boys in their ordinary, everyday world; those have the look of Arri/Zeiss Ultra Primes — spherical and flatter. When the boys set out on the quest and the adventure really kicks in, we switch to the more ‘characterful’ anamorphic-lens distortion. For the third act, we were inspired by Cooke S4s, somewhere between the clean Ultra Primes and the characterful anamorphics. [Related: Toy Story 4: Creating a Virtual “Cooke Look”]

When you’re lighting, are you referring to real-world fixtures? Do you say, for instance, ‘Let’s put a 20K here and a 2K with a Chimera over there’?

Calahan: Well, we can say, ‘I want the equivalent of a 20K over here,’ but we don’t really do that as much as just emulate that look. Mostly I’m looking at the quality, intensity and color of a fixture. We do have the capability of analogs, but we generally work with basic shapes and sizes rather than try to replicate what a 20K would do. One thing we can do that most cinematographers would envy is put a light anywhere we want, even in shot. If I want a fixture right between the characters, I can do that and it’s invisible, so we don’t have to worry about hiding it — we just get the effect of it. That can be magical and kind of fun. If the light is bouncing off green grass and making the skin tone go weird, I can just put in a different-color invisible reflector and change that light color a bit to get what we want. The tools are based on real physics, but they are still only an approximation of reality. There is still a lot of room for interpretation, enhancement, stylizing and fudging physics. We can create a bit more of a painterly look than someone who’s trying to stay strictly photorealistic.

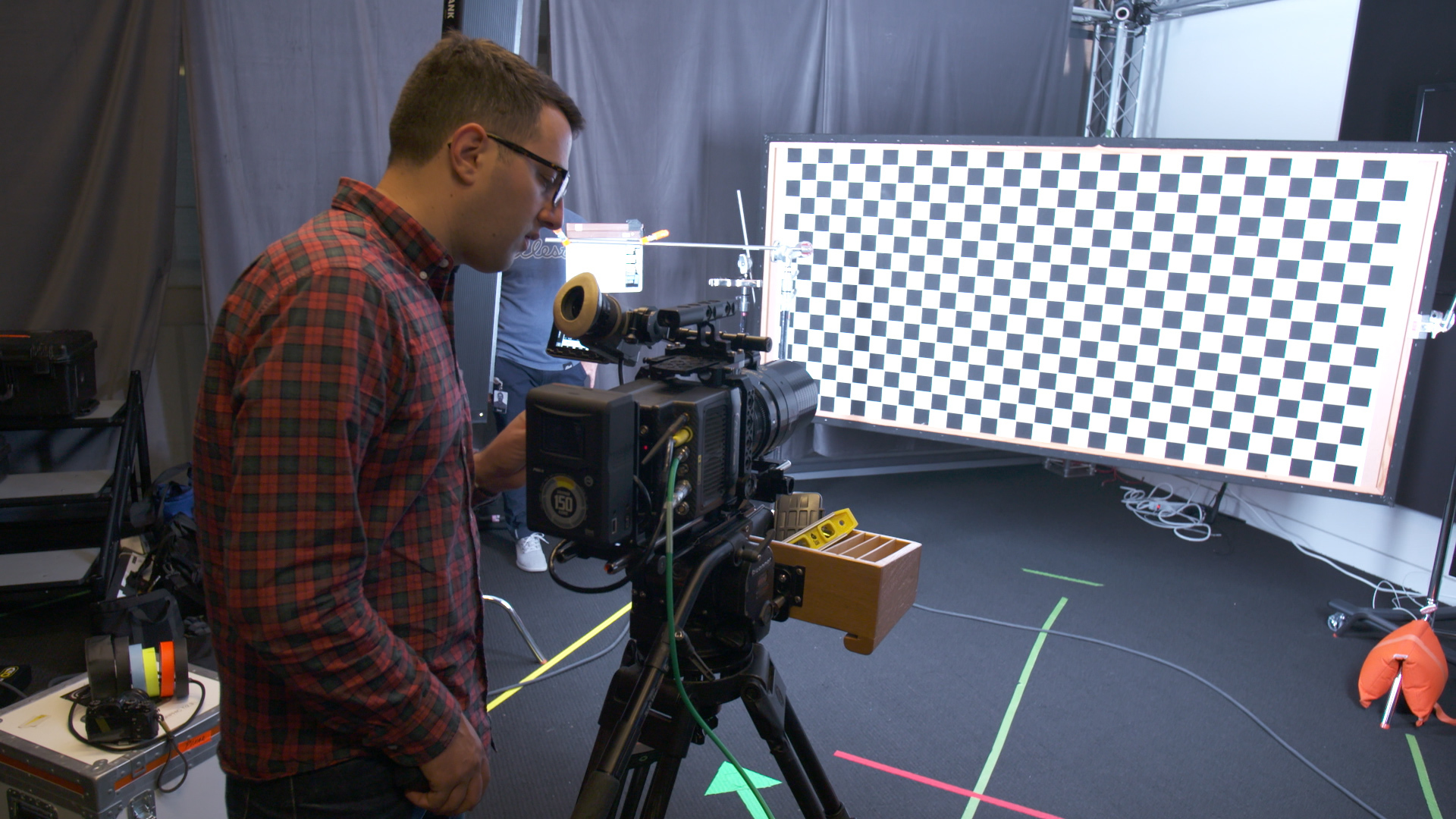

Habib: [Early in prep] we do what I call weird science experiments, for lack of a better term. We might have a live-action shoot where we’d have an actor stage some action as a way of throwing out some ideas. Or we might try to demonstrate photographically what we mean when we say ‘anamorphic look’ — ‘Do you like this or not?’ To try to get an idea of what it might look like when the boys attempt to conjure their dad and only succeed in bringing back his legs, we put an actor in a greenscreen suit, put pants and shoes on him and shot him running around as live action. And sometimes our experiments weren’t literally about a look or feel; sometimes it was just about getting the crew inspired. Since Onward, we’ve started a classroom-based internship to teach students our Camera and Staging process. We had a rep from Zeiss up here to show [us] some new lenses, and we had a [Sony] Venice set up with a fluid head. I invited the interns to give it a try — to just pan and tilt the camera to get a feel for it. Most of them came from a pure art-school or animation-school background. I wanted them to get a sense of the resistance of the head and the weight of the camera, and to look through the viewfinder. It’s enormously helpful for CG artists to get that real-world experience.

Do you incorporate imperfections into your work in order to emulate reality?

Habib: [We do,] but sometimes they’re very hard to keep in! On Inside Out, we tried to have a moment where we missed focus, like the focus was too slow coming onto the character, and we had to have that argument — that discussion — no less than 20 times as that shot went down the pipeline. The artists would think it was a mistake and fix it, and then we’d have to put it back in! So some imperfections are easier to build in than others. For Onward, we used motion capture on some of the cameras to capture the feeling of an actual operator responding to the performance of the characters. And we had a Steadicam operator, Nick Schwyter, come in and create a library of various common motions such as walks, runs and creeps. Our lead artist, Jan Pfenninger, ran those mocap sessions. Finally, because a good part of the movie is traveling in vehicles, we shot live-action footage from various car mounts and our other lead artist, Leo Santos, tracked the camera vibration using [Foundry’s] Nuke. We layered all these imperfections into the shots to create that physical believability.

In most of the sequences of Onward that I saw, I noticed there’s a fair amount of depth of field.

Calahan: [Laughs.] Yeah, we talked about that a lot, especially early on, to decide what the general feel of the whole show would be, including the depth-of-field guidelines, light levels and how they might change for time of day, desired apertures, shutter speed, ISO, et cetera. And then we’d get in there, take a pass at it, look at it and decide what we liked. And we’d come to some sort of consensus that made both of us and the director happy.

Habib: Sometimes Sharon would say, ‘Can we open up one more stop?’ and I was usually like, ‘Yeah! Let’s do it!’ We developed some tools on this film to be able to track focus more closely. The tool was a bit like ‘false color’ exposure mode, but for focus — whatever was in front of the depth of the field would go yellow, whatever was behind it would go red, and whatever was in focus would be green. With shallower f-stops, we had to keep a closer eye on what was sharp and what wasn’t [so we used this false-color system for our reference]. You wouldn’t think you could end up with an accidentally out-of-focus character in animation, but you can!

What software are you using?

Calahan: Our camera-layout software is the same one our animators use, proprietary software called Presto. Our lighting software is a heavily customized version of [Foundry’s] Katana. We use RenderMan as our renderer.

It’s wonderful and fascinating that Pixar places so much importance on the art of cinematography. We’re seeing that art expand far beyond traditional photography, and you both represent that new path beautifully.

Calahan: Thank you! It is also very inspiring for us to see the kind of work Chivo Lubezki [ASC, AMC] did on Gravity [AC Nov. ‘13] and Caleb Deschanel [ASC] brought to The Lion King [AC Aug. ’19]. Seeing that crossover is really exciting. In animation there are very few rules. You can do a film like Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse [listen to the AC podcast here], which has a very 2D, hand-painted look, or you can do something like The Lion King, which is trying to be much more photo-real. It’s really a very wide palette to play with.

Habib: It’s wonderful to see traditional cinematographers become more involved in the animation world, because it’s all cinematography. It’s all about the lighting and the camera; those are the common links between the virtual and physical worlds. When there is a lens and there is light, there is cinematography, even if those lenses and lights are virtual! And in the end, an animation director of photography and a live-action director of photography are concerned with the same thing: How are we telling this story with the visuals?

Calahan: It’s all about making images.

Ardent Supporters

In 2013, Sharon Calahan became the first cinematographer to be inducted into the ASC for work in animation. AC recently spoke with some of the ASC cinematographers who championed her for membership.

Dennis Muren, ASC: I was really pleased that the Society chose to bring her in. I saw a real parallel between the work she was doing in animation and the work I was doing in miniatures, stop-motion and full-size effects. Looking at her work, it’s clear she’s dealing with the same problems we deal with in real-world photography; we’re both trying to tell stories in visual media.

One of the things I find interesting is that Sharon is dealing with synthetic lighting and creating looks not exclusively [based] on where lighting would be in the photographic world. She starts off with a black-and-white image of a frame that represents the look she’s going to light, and then she colors it in to what looks right to her sensibility, and within certain ranges there’s a lot of cheating she can do that would be impossible in actual photography. Adding her sensibility to it, she’s looking for the emotional impact, just like traditional cinematographers. And what she ends up doing is just so darn beautiful!

I wanted to get her into the ASC because the work she’s doing is at the forefront of where a lot of our techniques are going, and we need artists with her skills to make digital characters indecipherable from real ones. I stopped giving predictions on the future because it’s always the public that decides — not us — but what Sharon is doing is certainly in the category of the future of cinematography.

Steven Poster, ASC: I was introduced to Sharon on a kind of field trip to the Pixar campus, and as I sat with her, I realized that what she does is every bit as photographic as what we do. She also has a deep knowledge of color and of the mechanics of workflow; at the time, she was working on designing [how to] transfer color from linear to log in the digital-animation system so it would look much more like motion-picture film.

It dawned on me that this was what’s next — this was what we’re going to be calling cinematography and the director of photography. I just thought this was a great opportunity for [the ASC] to move into a new phase and recognize the expanding realm of the cinematographer. Her work is not too far from the kind of work Chivo [Lubezki, ASC, AMC] did on Gravity.

Sharon is a painter; she’s got a fabulous eye and an amazing eye for composition, light and texture.

Stephen Goldblatt, ASC, BSC: One fall I was going to Pixar for screenings, and at one of them, I was asked to meet Sharon, look at the work and go through her workflow. Pixar was of the opinion that she should be credited as a director of photography, and I agreed. She was the cinematographer on Ratatouille in every way. The work I saw her doing was in essence the same kind of work I had been doing all my career. She’s responsible for the look of a film from beginning to end, and it absolutely makes sense to me that she be recognized as a cinematographer.

It really comes down to how you define cinematography. If you don’t confine it to the traditional crew and traditional photography, then the definition becomes a lot looser to cover those individuals who combine artistry and mechanics to create images, and animation therefore is definitely included. The cinematographer could be broadly defined as a visualizer. That’s what Sharon does, and that’s good enough for me!

In the end, the job of filmmaking is a puzzle, and cinematography is central to the look of the film. Her films all have very specific looks to them. That’s her job; that’s what she does. I was very impressed by her talent and subsequently found that there was definite support for her to become an ASC member.

Daryn Okada, ASC: I met Sharon in the mid-2000s, and spent time learning and recognizing that her creative approaches and responsibilities were similar to the challenges and artistic partnerships of live-action cinematographers. Many times in animation, a person may have screen credit as “director of photography,” but their duties may not be [those of] a cinematographer. Sharon approaches every project from a truly creative place that arrives from visual storytelling. She takes a story, researches it, and scouts locations to get their essence, colors and textures in [service of creating] the movie’s image.

During production, Sharon supervises her crew like a live-action cinematographer. She works closely with the director to visually interpret the story. She does everything a cinematographer does, only it takes longer! In some cases, what she does is harder because she’s literally starting from a blank page, whereas we might have sets or locations to begin from. Sharon also has to consider the different characters, their skin tones and facial features, and figure out the best way to light and photograph them in every scene — exactly the way we do with real-world actors.

From doing visual-effects movies as a cinematographer, I never took it for granted that images added later would just fit in with what I shot on set, so I stayed involved in postproduction to work with the digital lighting process. When Sharon was proposed for ASC membership, I was able to communicate with other ASC members the parallels between what she does and what we do. She was also able to transfer from the animation branch to the cinematography branch of the Academy.

The cinematographer’s job is to interpret the story visually, and that’s exactly what she does, with similar tools, approaches and concepts. She’s a perfect match for the ASC.