Owen Roizman on Filming The Exorcist

The director of photography on what may be the most shocking film ever made describes the unique problems and challenges involved in translating a best-selling novel into stunning visual images.

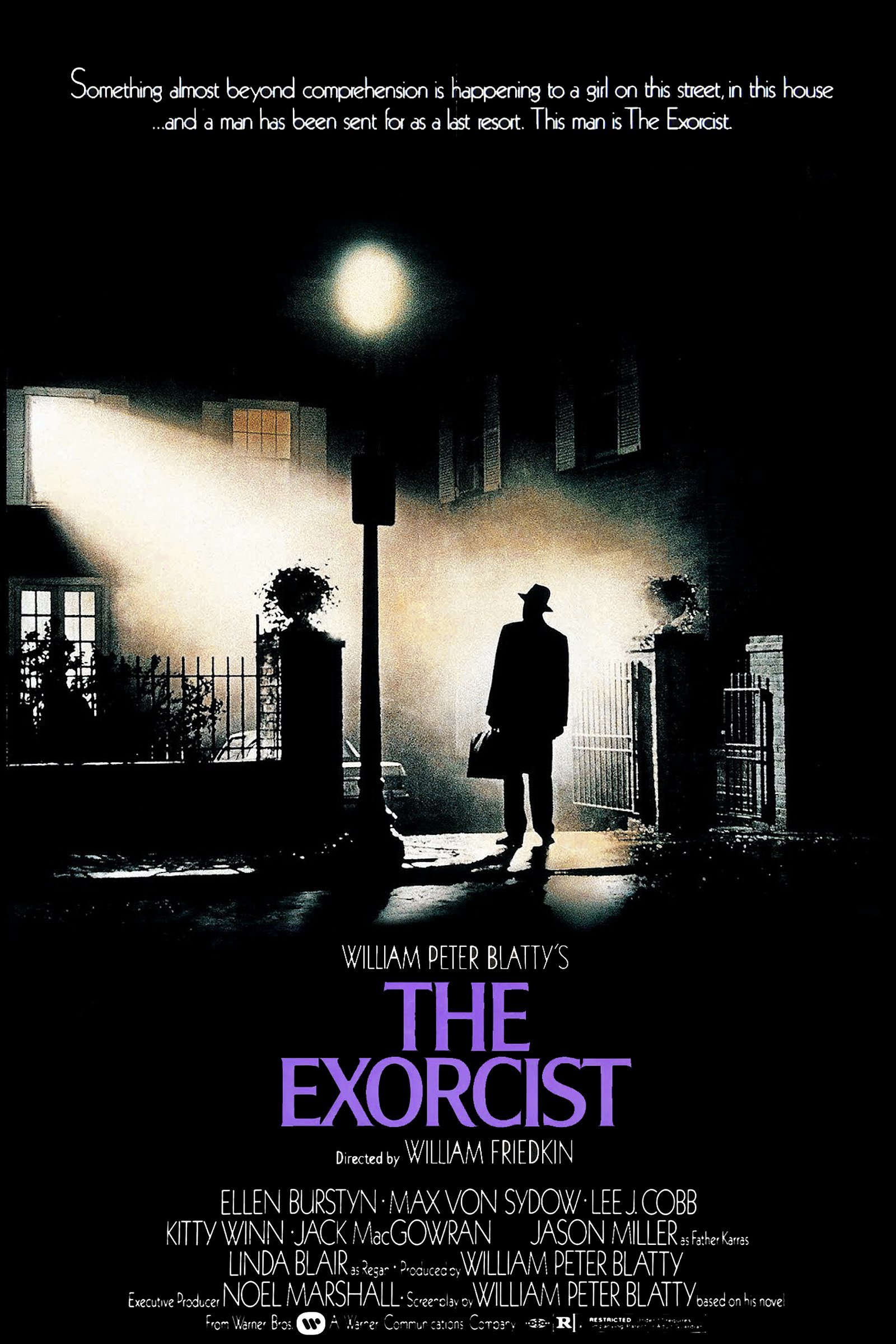

Probably the most eagerly anticipated film of the year, the Warner Bros, screen version of William Peter Blatty's best-selling novel, The Exorcist, is now in current release, having just made it under the wire for Academy Award-qualification screenings.

he making, The Exorcist comes to the screen as a jolting horror story, so shockingly faithful to the book that it makes films like Rosemary's Baby and Hitchcock's Psycho seem like bedtime stories by comparison.

Its theme plunges into that shadow area of parapsychology known as "demonic possession" and the victim is a lovely, innocent 12-year-old girl who is turned into an obscene bloody monster as Satanic forces take over her body and soul. The bulk of the film is concerned with the titanic struggle between God and Devil, as Jesuit priests are called in to exorcise the demon spirit and cast it out.

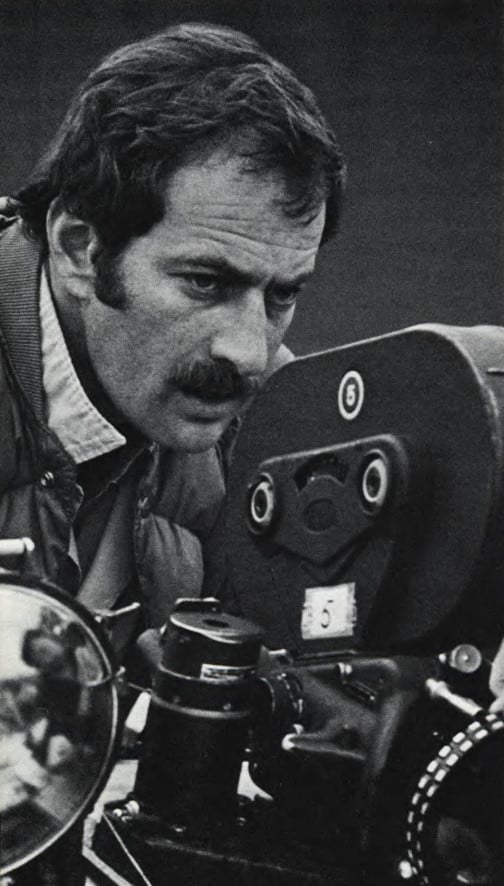

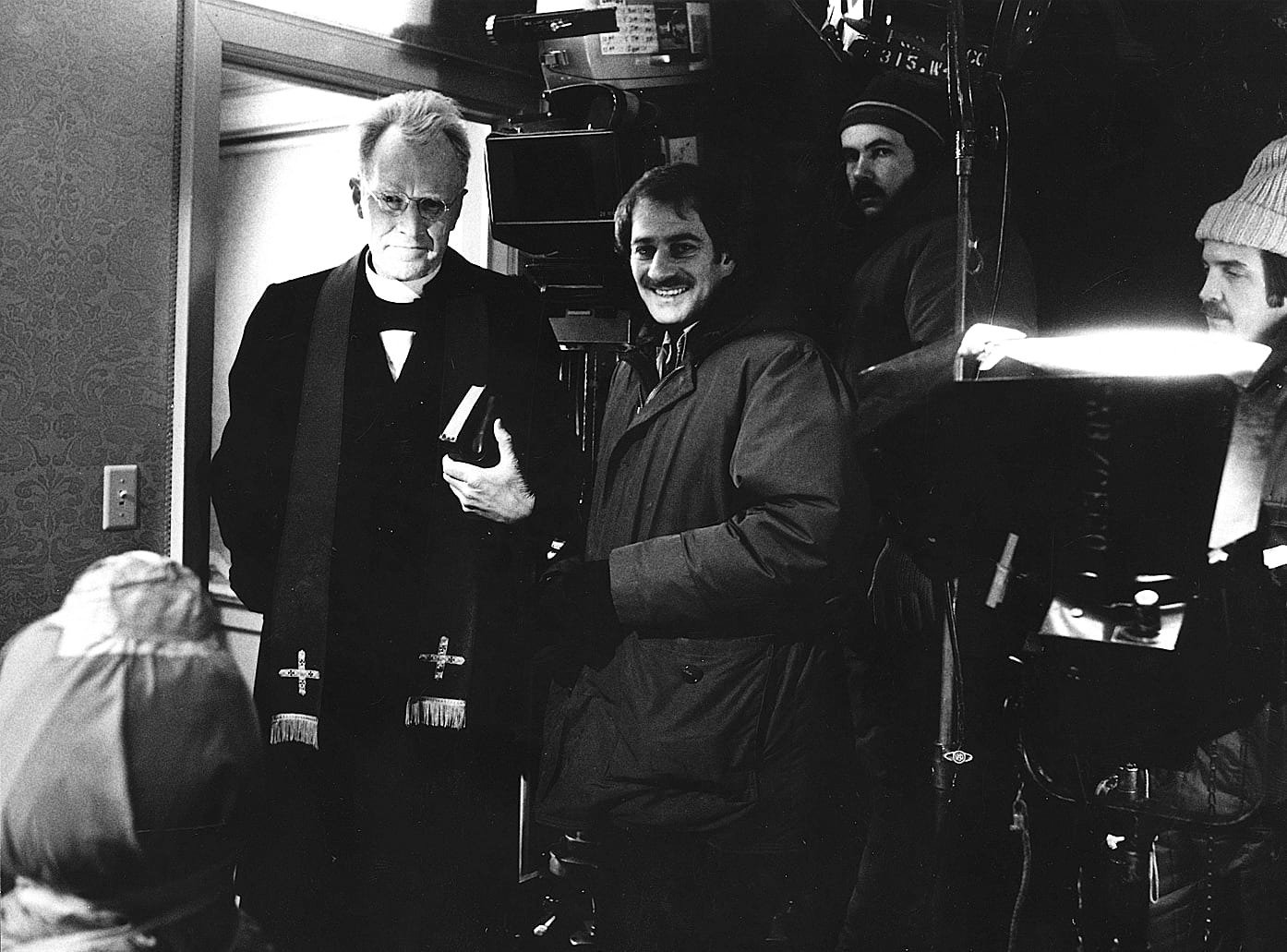

Directed by William Friedkin and photographed with chilling mood by Owen Roizman (the crack director-cinematographer team that made The French Connection), the film is a triumph of technical virtuosity. Ingenious mechanical special effects by Marcel Vercoutere and horrifyingly realistic makeup by Dick Smith combine with Roizman's stunning cinematography to create and sustain mood that builds to a hair-raising climax.

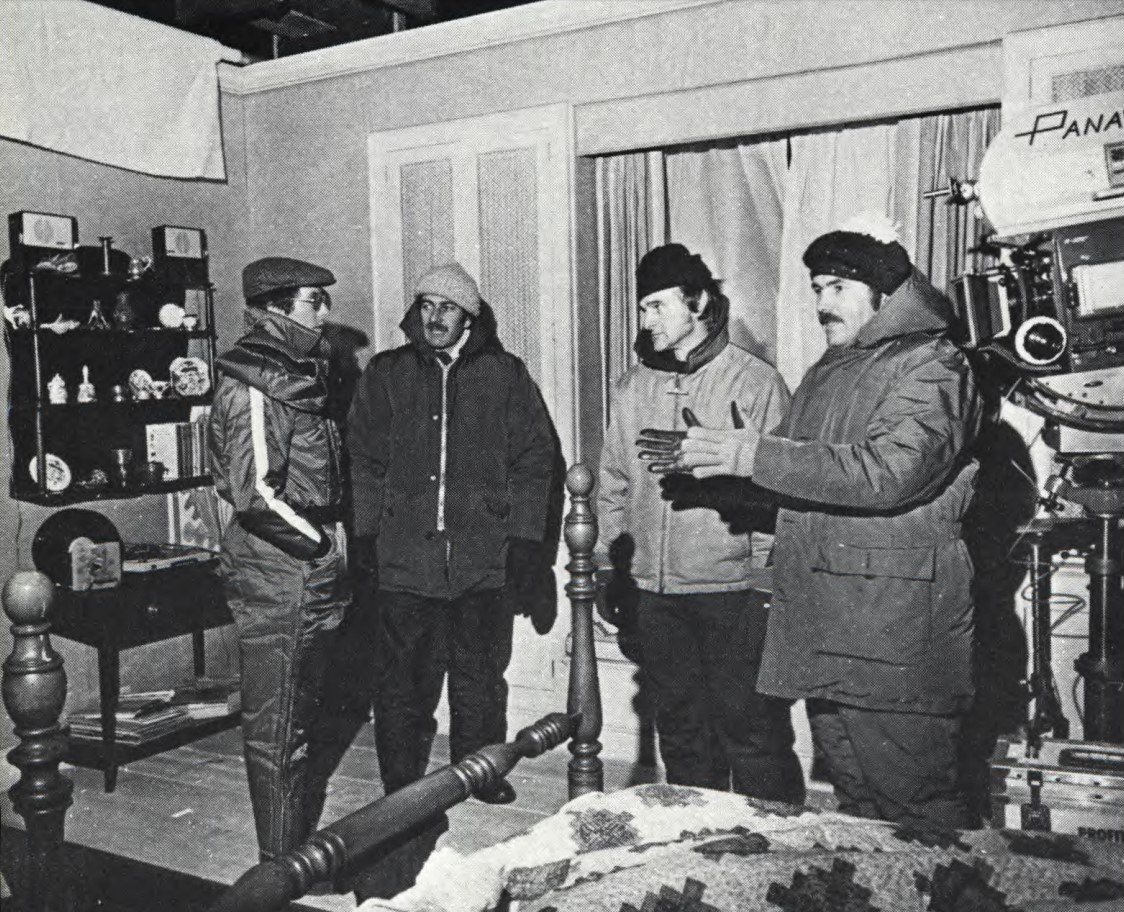

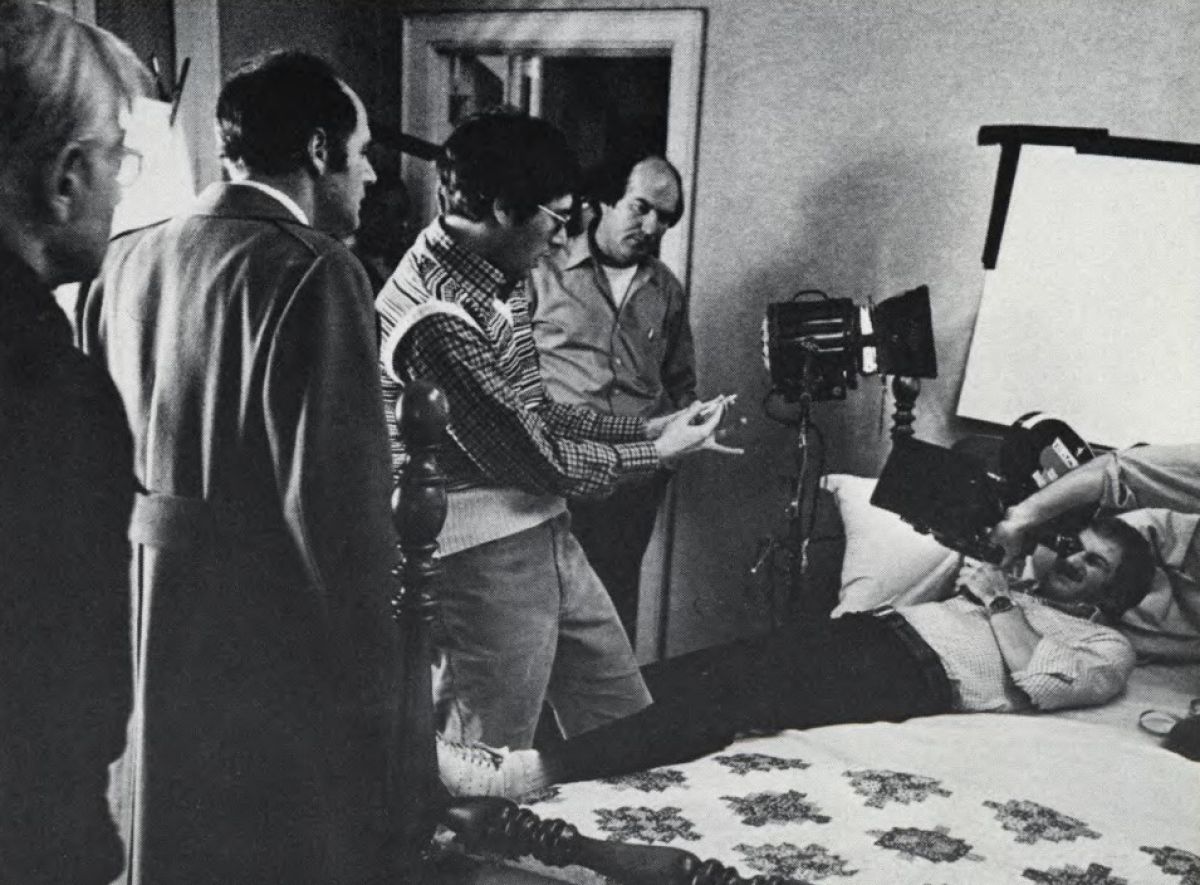

Except for a short prologue filmed in Iraq (and photographed by Billy Williams, BSC), the entire film was made in the Washington, D.C., suburb of Georgetown and on studio sets in New York City. The lengthy exorcism sequence takes place within a single confined set (the child's bedroom) which had to be refrigerated to 20 degrees below zero in order to achieve the requisite chilling effect.

In the following interview, director of photography Owen Roizman discusses the unique problems and challenges involved in the filming of The Exorcist:

American Cinematographer: Can you tell me how you became associated with the filming of The Exorcist and how you arrived at a particular photographic style for the picture?

OWEN ROIZMAN: I became associated with the picture through the director, Bill Friedkin. We'd made The French Connection together and he figured that since we'd done so well the last time, maybe we could do it again. When we first discussed the picture we naturally discussed style and he said that he would like this film to have a realistic, available-light look — very natural. But he said that he would like to take it a step above what we did the last time and not go for such a raw documentary feeling. It was to have a little bit slicker, more controlled look to it — and that's what we attempted to get. The sets were very normal. We didn't go for a Psycho type of house. All the rooms were basically designed to be elegant and well-furnished — a warm and moody house. What we tried to do, by means of the lighting, was to give it a kind of ominous feeling — as if some lurking, mysterious thing were hanging over it. That's about as far as we went with photographic style.

The story of The Exorcist involves some very bizarre happenings — to put it mildly — most of which take place in the child's bedroom during the actual exorcism. What were some of the more unusual photographic problems you encountered in getting this action onto film?

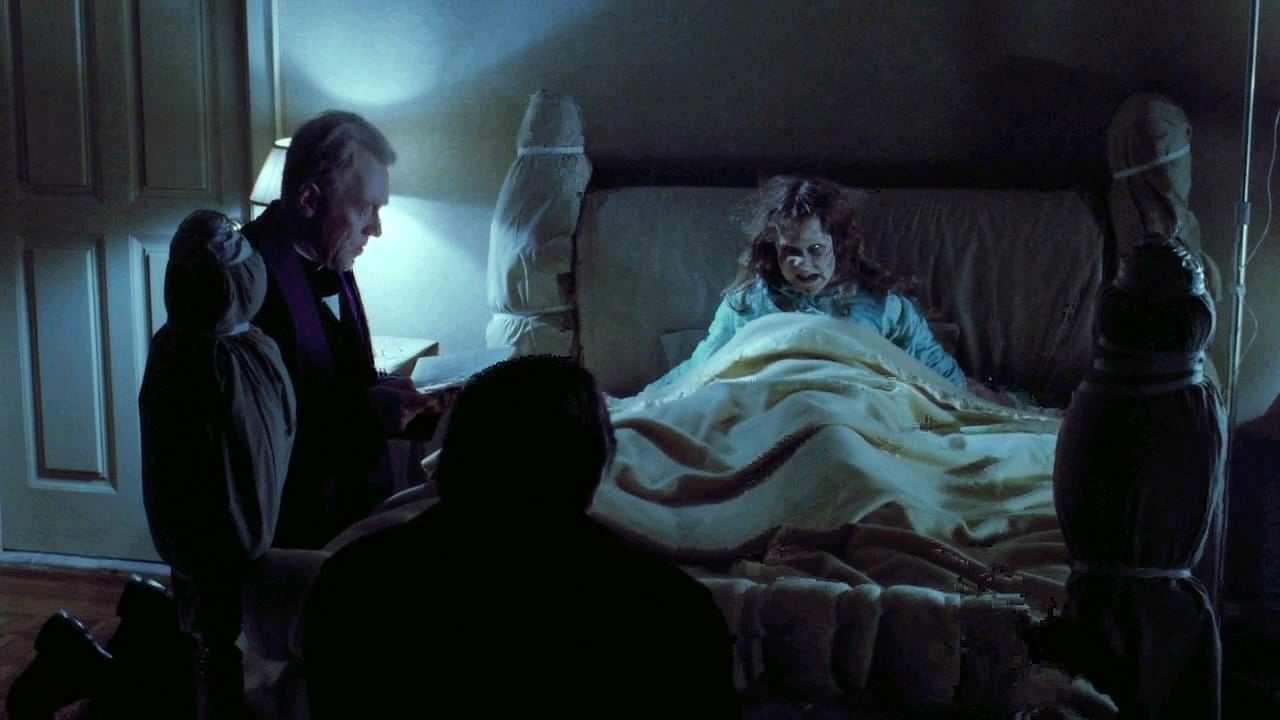

The exorcism sequence did involve some very special problems. One of these stemmed from the fact that in the story anyone who walks into the child's room becomes extremely cold and develops a chill. The only way you can really show that kind of cold is to be able to see the breath of the characters — and the only way to see this breath is to actually have them in a very cold room. For this reason, the child's bedroom was duplicated and built inside a "cocoon" — as they called it — which was refrigerated, generally to about 20 degrees below zero. We tried it first at just below freezing (about 25 degrees) and you could see some breath, but it really wasn't enough and as soon as the lights were turned on the heat took care of the cold so quickly that we couldn't even make a take. We found out during the test period that this wouldn't work, so we went back to the drawing board. A system was developed that could refrigerate the room quickly to any temperature from zero to 20 below. The breath showed up fine at zero, but Friedkin wanted the actors to really feel the cold because he felt that would help their acting. An actor on his knees for 15 minutes at 20 below zero is really going to feel cold. It worked out very well.

What did you do to get the breath to show up distinctly?

The only way we could get the breath to show was to backlight it. This created a problem, because the light source we had to work with was always coming from right next to the bed and the two priests who were performing the exorcism were always facing the light. Had we backlit the scene it would have looked like light coming from some phony source. The challenge was to get backlight on the breath while keeping everything else dark. This is simple to do if you're shooting a still photograph, because the person doesn't move. You can set a lamp in and cut the light off his face and body and there is no problem. But with the actors moving all the time, it got to be a bit difficult. It was always a matter of finding a place to hide the backlight and finding a way to keep it off of the actors.

In the story of The Exorcist there are a lot of weird and sometimes quite violent physical manifestations that take place during the exorcism. How were these handled?

There were many special effects that had to be executed during that sequence. The bed levitates; the child levitates; the room shakes; the ceiling cracks; the curtains blow suddenly, even though the windows are closed. All of these effects had to be seen and the room had to be designed with them in mind. The walls and ceiling were all wild, of course, and there wasn't much of a problem up to the point where the ceiling cracked. After that we had to use a hard ceiling and moving it around became quite a time-consuming number, since it was seen in some shots and not in others. When the girl levitated we had to pull the ceiling out completely around her, so that they could move in the rig with the wires. Then it was decided to do a shot which included a great deal of the ceiling while she was levitating. That meant cutting a hole just big enough for those wires to go through, so we decided to build a ceiling that was shaped around the rig. There was a ceiling all around, except where she would levitate.

What about the problem of keeping the wires from showing up?

I've always found it easy to hide wires when shooting against a background of normal tone. I've done it many times before in shooting commercials simply by painting the wires to blend in with the background. But in this case, the girl was moving through such extremes of background light and shadow that it was enormously difficult to hide the wires. We had to practically paint them frame by frame. It was almost like doing a frame-by-frame retouching job all the way. Normally, skillful editing would compensate for the moments when the wires were visible, but Friedkin wanted to see it perfect all the way, from top to bottom.

In the book, during the exorcism, there's a moment when the little girl's head revolves 360 degrees on her shoulders. Were you able to create that effect in the film?

Yes, but it was a really terrific challenge. When you read something like that, it is easy to form your own visions of a head revolving, the shoulders straining and the neck muscles fighting against this tremendous force, but how do you make such a thing look believable on the screen? We had to use a dummy, of course, but our first attempt looked just like what it was — a dummy's head revolving 360 degrees. So we went back to the drawing board with that and worked out a couple of things to put some pulls in the clothing and we wrapped the hair around the neck to cover the separation between the head and body and got some movement into the arm and hand at the same time. Then one day, as we were looking at the dummy in bed in the cold room, I said, as a joke, actually, "Wouldn't it be great if the dummy had some frost on its breath?" Everybody looked at me, and the next thing you knew, they were working on it. When they put that element in it looked terrific. It was that one extra realistic touch that made the effect work.

Did you force-develop any of the footage?

Yes. We pushed all of the interior footage one stop — but none of the exterior. The conditions actually made it necessary. Because of the tight quarters, we could never get enough light into many of the sets. I shot 90 percent of the picture wide open, as usual. My poor assistant, Tom Priestley, had his work cut out following focus, but he's absolutely brilliant at it. He followed an actor in the back seat of a car coming toward us with the 500mm lens wide open and I can't remember a single frame being soft. He has magic hands. My operator, Rickie Bravo, did his usual extraordinary job, too.

Did any of the effects demand radical changes in lighting?

Yes. There is a part during the exorcism when the "demon" causes the lamps to go a little crazy. They would flicker and dim and do weird things and the lighting pattern would change completely. The one fundamental lighting change occurs when the room shakes and one of the lamps falls over. From that point on, one lamp is on the floor and the other one is still on the night table. This gave the set an entirely different look for the rest of the exorcism — and added to all of the problems. At the very end of the exorcism sequence, Friedkin wanted the room to have a completely different feeling, even though the basic source lighting remained the same. He wanted it to have an ethereal quality — a very soft, glowing, cool sort of thing. We tried, at that point, to work with absolutely no shadows in the room, using just bounce light — and I think we achieved the correct overall effect.

What kind of lighting units did you use inside that room?

We were always having people walking in the door and around the room and, because we were usually shooting from a low angle, we'd see almost the entire ceiling and three walls at one time. For this reason we had to hide the lights most of the time, so that, generally, the biggest lights we used were inkies, hidden wherever we could find a place for one. We were constantly controlling them with dimmers, so that if someone got too dose to one, we'd take it down. The lights were also very carefully netted and we'd grade the nets down as much as possible within the light, because we didn't have much room to put the nets away from the light and do it sharply. My gaffer, Dick Quinlan, is a brilliant guy. He had a dimmer in each hand and one of his boys also had a dimmer in each hand. They would sit and ride four dimmers at once constantly, and it was like playing a musical instrument. In fact, one day, just for a joke, I put some sheet music in front of one of them. Once in a while we'd use a slightly larger lighting unit — a 750-watt Baby Junior, or some zip lights — but during the exorcism, the set was almost exclusively lit with inkies.

Were there any other sets, other than the child's bedroom, that presented special lighting problems?

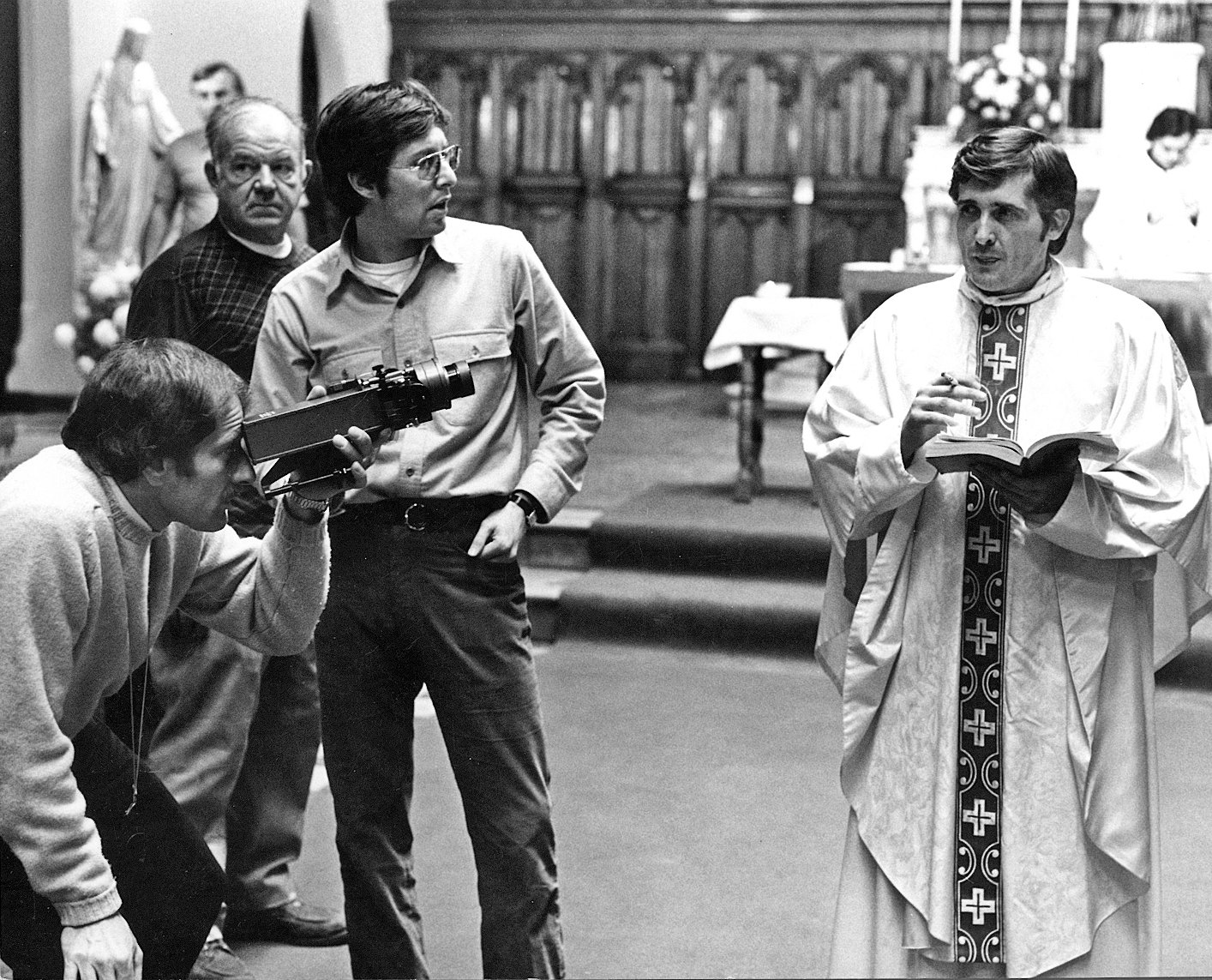

One of the biggest lighting problems in the picture was shooting inside the Chapel at Georgetown University. It's a big chapel and full of stained glass windows. Friedkin wanted to show the entire interior in an establishing shot and it required extensive lighting to give it an "available light" look. The guys in the crew did a terrific job on it because it really was back-breaking work to rig Brutes up on 30' parallels — but the results were quite pleasing. We had other problems in the basement set of the house, which was built with a very low 7' ceiling. There was really no place at all to put lights and, in doing any sort of pan around or dolly shot, we would have been fighting ourselves had we tried to use conventional lighting units. There were a few practical bulbs in the ceiling of the basement and we simply replaced these with photofloods and used these as our lighting. It worked out very well.

Were there any other location interiors that involved unusual challenges?

There was one sequence in which the little girl goes to the hospital to get examined. We shot it at the NYU Medical Center and the only time that we could get the use of the facilities was on a Saturday afternoon. Our "sets" were actual x-ray rooms that they regularly use for patients and we had a very limited time in which to do what we had to shoot in there. The space was cramped and there was really no room for rigging lighting equipment, so I decided to shoot the whole thing with available light, which, in this case, meant fluorescent light. There was plenty of light in there and I was actually able to stop down. A couple of the rooms had different colored fluorescents, but we stuck with whatever color happened to be where we were shooting. The only alteration we made was in the hallway, where we changed the bulbs to a different color, so that they would match those in the rooms a little bit better. The results were so good that when we shot a later sequence in a doctors' complex on Long Island — where we had plenty of space and complete control — we decided to use the available fluorescent fight, also. We didn't use gels on the windows to correct the exterior light; we just pulled some shades to balance things up. We had so much light from the fluorescents that I was able to put color correction filters in the camera, so that there was virtually no correction necessary in the lab, and the results were the best that I've ever had with fluorescents. It became so simple to shoot there that we could just go from one shot to the next with great speed.

Still photographs from The Exorcist indicate that you had some rather extensive night-for-night exteriors to light. Could you tell me about these?

We shot night exteriors in Georgetown and the trickiest one was the scene where the Exorcist himself arrives at the house. It's late at night and the shot starts with the camera pointing down the desolate, foggy street. Two headlights appear out of the fog and we see that they're coming from a taxicab that swings around in front of the house. The priest gets out and stands in the bright glow coming from the little girl's bedroom window, it was difficult to get that bright of a glow from a shaded window and we also had to hold a fog effect all the way down the street. Of course — wouldn't you know — just as we were ready to shoot, the wind came up, which made it more difficult to keep the fog settled in. But we shot as fast as we could and managed to get the scene. At this point, I haven't seen the final print and I don't know exactly how it's going to come out, but from the dailies I saw in Georgetown (which were not projected under the best conditions), it would appear that I may have overlit those night exteriors a bit. It was such a great looking street that I guess I was afraid to throw any of the detail away, and so I lit it more brightly than I ordinarily would. However, with proper printing. I'm sure it will come out dark enough. The rest of the night exteriors were fairly basic, except for a scene at the end where the priest jumps out the window and down a flight of 86 steps to his death, it was a long narrow chute of steps and lighting that was a big number, also. Actually, I think we did it rather well, as far as speed was concerned, because we again used as much available light as possible and just augmented it with a little fill light where necessary.

One of the production stills shows you sitting in a curious kind of swinging harness-like rig, while lining up a shot. Can you tell me what that's all about?

We had a shot in which three people enter the front door of the house and race up a kind of half-winding staircase and into the bedroom on the second floor. We wanted to take them from the front door and stay in front of them as they go all the way up the stairs and around the curve, then back up and let them pass by us and then swing in behind them and follow them into the room. Needless to say, it was kind of a difficult thing to achieve. We built a special chair rig, which the grips did an excellent job on. They used an electric hoist and had to physically lift the Operator and carry him up the stairs in perfect synchronization with the people coming up in a diagonal tine.

Then they had to swing around and maintain the distance and try to do it without any bumps on the screen. The shot works beautifully. Unfortunately (or fortunately, I guess), you are never aware of how much effort went into that shot because it looks so simple on the screen. Of course, once we had figured out how to do it physically, the next problem was how to light it without having our own shadows all over the place, we achieved the desired result with very indirect overhead lighting pumping light through muslin all over the place. The lighting units were simple — just photofloods and little strip lights beamed through the muslin. We had to achieve a balance, also, in passing by a window and seeing into a room downstairs that was supposed to be dark. If I were to do that shot over again, I would probably underexpose a bit more to accentuate the shadows, but, all in all, the shot worked very well.

The Exorcist was shot in color, but since so much of it involves heavy mood, did you do anything special to mute the color?

This was most important in the little girl's bedroom where most of the heavy dramatic action takes place, and, with that in mind, the room was designed and decorated in a very monochromatic way. The walls were a kind of gray-taupe color and the bed sheets were a neutral beige. The priests were dressed in black, which helped, but we stayed away from white completely because it would have jumped out too much. In toning everything down like this, the only real color in the room became the skin tones — an effect which I personally like very much. This sequence has an almost black and white feeling; yet, there is subtle color there. In the rest of the picture we let the color play normally. The house set was well designed and the main reason it was difficult to shoot in was that we kept the ceilings on much of the time. Doing any big moves with people while showing the ceilings involved the constant problem of hiding lights, while trying to maintain a realistic look. Also, Friedkin demanded complete realism. He wanted to see pictures with glass in them, mirrors on the walls and all of the other highly reflective surfaces you would naturally find in a house, we never tried to cover anything up, as we would normally do for expedience in shooting. I've had constantly to contend with glass doors leading from one room to the other. The kitchen had a low solid ceiling and was all done in stainless steel, with a big picture window at one end and a glass partition with cabinets right across the middle of the room — which made lighting that set virtually impossible. That kitchen was actually lit with two little practical fixtures built into the ceiling — and that was it. Whenever we could sneak in a little light to pick up a face or dean up an area, we did it. Other than that, we'd walk in, hit the switch and shoot — through not much choice.

Now for the silly question: If you were asked to sum up your basic philosophy of cinematography, how would you state it?

My theories on cinematography are rather simple and basic. My style — if I have one at all — is simply to approach a subject and try to record it on film as it should look, rather than as I might want it to look. In other words, if you are going into a dirty, dingy area, don't try to make it look like anything else; shoot it to look dirty and dingy, if you are shooting something that is supposed to look beautiful, then try to make it look as beautiful as it actually is. My approach, really, is to take a situation and recreate it on film as it is and not change it — not take something ugly and make it beautiful, unless the story calls for that. Whatever my eye sees, I like to see on film — which is not always easy to achieve.

Don't you think that recent advances in cinema technology make it somewhat easier to achieve — the new fast lenses and film stocks and all that?

Oh, yes. There's no question that the new fast lenses allow you to get some of these things on film without doing anything to change them, in the old days you always had to pump light into such areas to get an exposure, and once you pumped the light in there it never looked the same. Some of the things we shoot today with available light simply could not have been shot that way five years ago. There was just no way. On my next picture, [The Taking of Pelham One Two Three] which takes place mainly in a subway tunnel, I'm going to use the fastest lenses ever made and shoot them wide open with existing light whenever I can. A few years ago if I had tried to do that, I would have ended up with a very grainy film. I want it to look dingy, but not grainy.

After you shot The French Connection, which won such praise for its raw, almost documentary realism, there were those who were inclined to think that this was your style — period — and that you couldn't do, let's say, a glamour picture if you had to. Would you care to comment on that?

I get a kick out of that, because my whole training ground in cinematography was in the shooting of commercials, where you always had to try to make things took pretty — glamorous product shots, where you were always going for high-key, beautiful, diffused-looking footage, in fact, because I had done so much glamorous high-key photography, when I was approached to photograph The French Connection, I was asked if I would be able to shoot a subject that was low-key and "dirty", as they called it — and my answer was: "Why not? I'm a cinematographer. I should be able to adapt to anything." Now, after the success of The French Connection, even some of the people I knew before have branded me as a low-key, documentary-style photographer and I get a chuckle out of it, because it just isn't like that. One has to adapt from one picture to another and I've tried to change my style to adapt to each different subject — sometimes successfully, sometimes not — but at least I've tried to adapt to the particular subject I'm working on.

To wind up our discussion, do you have any final comments you'd like to make about the production of The Exorcist?

I think Billy Friedkin did a brilliant job of directing the film and I hope it's a huge success, because he put a lot of sweat into it. Everybody on the picture did, really. All of the technicians did a wonderful job. Dick Smith's makeup work was outstanding, as were the special effects. The laboratory work of Bernie Newson and Dan Sandberg at TVC was excellent, it was an extremely difficult picture to make, because the subject matter was so off-beat that nobody was really sure how to deal with it. For this reason, there was considerable trial and error involved. Sometimes we'd shoot something and think it was great; then we'd see it at a screening and realize that it just didn't took believable and we'd have to do it over. We had constant — and quite unique — problems to deal with. However, everybody pitched in and did a whale of a job under great pressure most of the time. But the pleasure of working with such a talented cast of actors more than compensated for those pressures.

The cinematographer was interviewed about the film many years later as part of the ASC Legends series. Here's a clip from that discussion, in which he discusses The Exorcist:

Roizman earned an Oscar nomination for his camerawork in The Exorcist — and was also nominated for his work in The French Connection, Network, Tootsie and Wyatt Earp. For his contributions to cinema, he was presented with an Honorary Academy Award in 2018. This tribute reel was played at the ASC Clubhouse during a party in Roizman’s honor, celebrating his achievement:

Roizman was previously honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 1997.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.