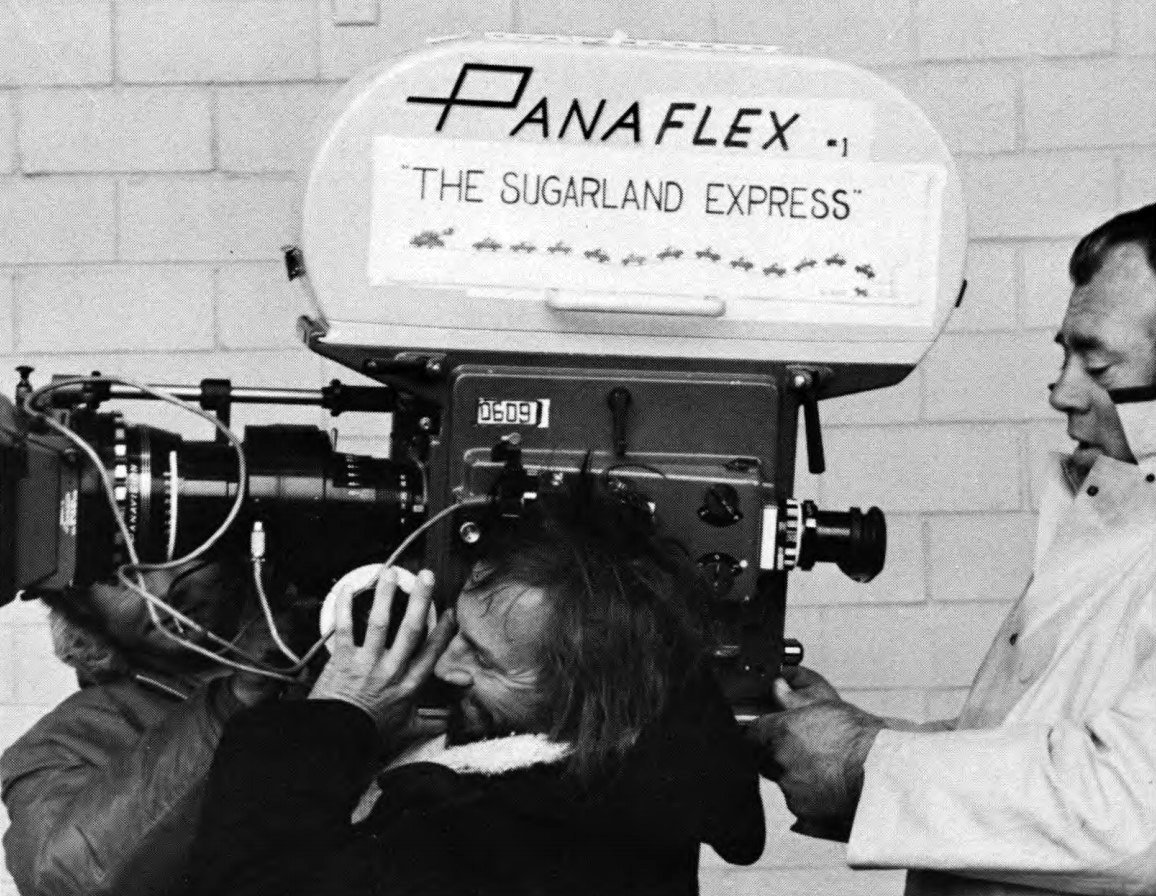

Panaflex Camera Debuts on The Sugarland Express

Long-awaited, the sleek new equipment arrives on location in Texas for the shooting of Universal’s ambitious road picture.

San Antonio, Texas — Ever since the recent unveiling of the new Panaflex 35mm camera before select groups of goggle-eyed technicians in Hollywood, London and Tokyo, there has been rife speculation as to which film would be favored with the first usage of the new equipment in actual production.

The prototype had been tried out on several features for a few days at a time, but now (as rumor had it) the first production model had come off the line at Panavision's spectacular new plant, and the question hung in the air: Who would get it?

A call from Panavision president Robert Gottschalk finally dispelled the mystery. He told me that he had received more than 130 "firm" requests for the new camera and, after much agonized soul-searching, had decided to send the first production model to the company shooting the current Zanuck/Brown production for Universal, The Sugarland Express. This feature, Gottschalk felt, posed some unique photographic problems and would give the Panaflex an "acid test" kind of shakedown.

The new camera (a few weeks overdue) had just been shipped to the company, presently on location near San Antonio, and knowing that American Cinematographer readers were most curious to know how the Panaflex would perform in actual production, I decided to go along and report it firsthand. Which explains how I happen to find myself, at this moment, deep in the heart of Texas.

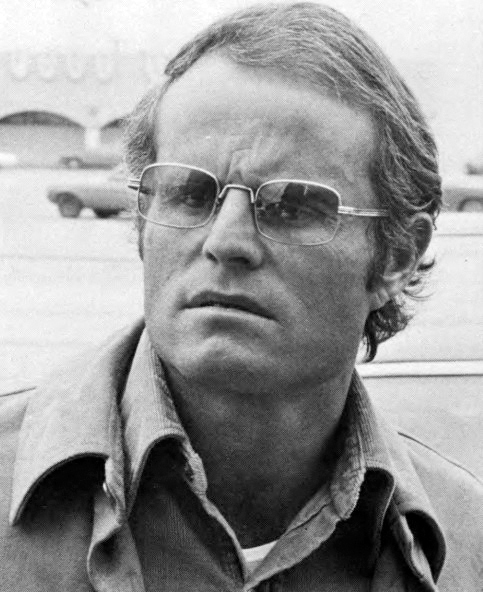

The director of photography on The Sugarland Express is Vilmos Zsigmond and, even though my plane arrives in the middle of the night, he is at the airport to meet me, looking as bright-eyed and bushy-tailed as if he hadn't just put in a 14-hour day on a rough location.

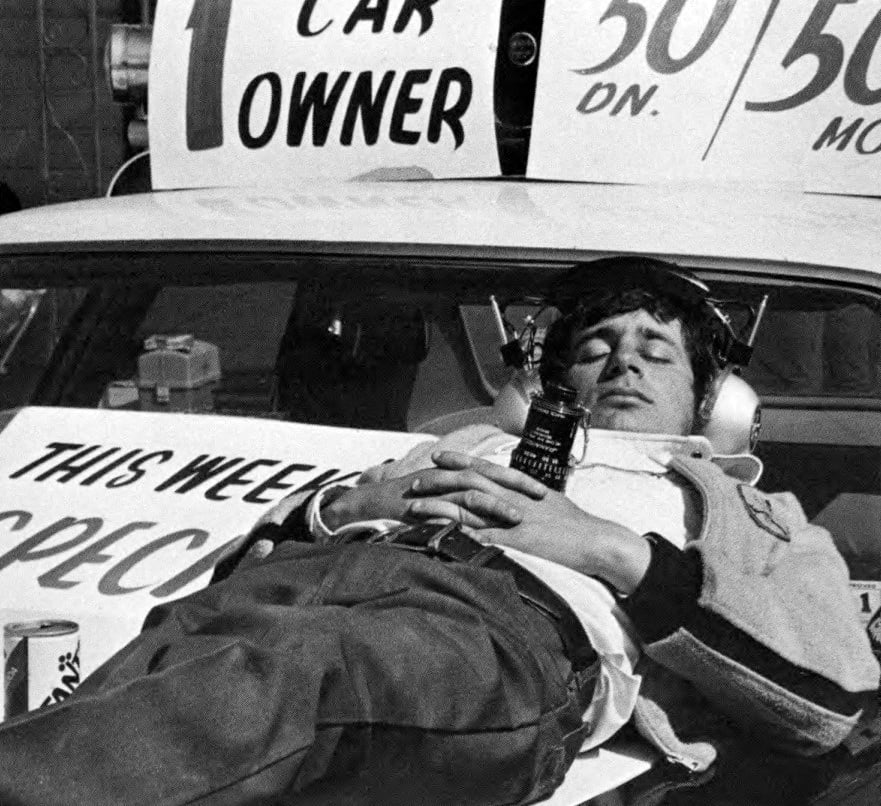

The company has been shooting about 40 miles away in and around the town of Floresville (3,701 souls), which is doubling for Sugarland. The next morning I ride out to the location with Vilmos and the picture's director, Steven Spielberg. He is 25 years old, highly-keyed, intense and exuding the air of a real pro. Although Sugarland is his first theatrical feature, two of his recent television directorial efforts, Duel and Something Evil, were among the top-rated TV movies of 1972.

"The story of this picture is a one-note, simple, beautiful tale about two young people who are trying to get their infant son back after he's been taken away from them by the Child Welfare Board," Spielberg tells me. "Both the husband and wife, Clovis and Lou Jean Poplin, had been spending some time in prison for aggravated petty larceny, and when the girl gets out of prison, she finds out that the authorities won't return the baby to her custody. She runs to the pre-release prison farm where her husband still has six months to serve and browbeats him into leaving the farm.

“He does his homework and he’s well-prepared — yet, when his eye sees something spontaneous on the set, he’s very adaptable and very creative. I think that when this film comes out he’s going to be a major director.”

— Richard Zanuck on Steven Spielberg

"What really begins the story is when they are pulled over by a highway patrolman for a routine check and the girl panics and takes his gun. They hijack the police officer and his car and take off. It's a very simple story that gets out of hand. What begins merely as a pursuit to get the baby back becomes an outrageous extravaganza, involving a caravan complete with 60 police cars and 200 civilian cars. The minute the media hear about it, the story gets onto the airwaves and everybody joins in. The number of police cars grows and grows because of the 'posse theory' they have in Texas, whereby, when a fellow officer is in trouble, police from all over the state come down to help."

It sounds like a laugh a minute — especially since zany Goldie Hawn is playing the hijacking wife/mother.

When we arrive on the location, the sight is impressive even to these jaded eyes. Strung out for more than two miles along the highway leading into Floresville are at least 250 vehicles of every description — half of them police cars. Their drivers (local folk) are milling around, sitting on the roofs, playing guitars and enjoying being part of a movie. Little do they know that they will be doing the very same thing eight hours hence.

As the crew sets up for the first shot, the Spielberg takes off on a little motorcycle across a field, “posting” as he hits each furrow. He's letting off steam, priming the creative juices, getting it all together. Meanwhile, I am introduced to the film's producer, Richard Zanuck. He's a quiet, pleasant man who, for years, ran the sprawling 20th Century Fox Studios. This picture marks his first time out as a working producer and it's clear that he's enjoying being in the big middle of the action. I ask him to tell me a bit about the dramatic characteristics of this picture.

"Well, the important action of this picture is what takes place inside the vehicle — police car 2311 — that has our principal people in it, Goldie Hawn, Michael Sacks and William Atherton,” Zanuck tells me. "It's the slow evolution of their personalities during a 36-hour period that is really the backbone of the story. What we are shooting out here today with all these people and all these cars forms a terrific backdrop to that wonderful personal story and very emotional drama that takes place inside the car. We've been able to achieve a very effective film on two levels — the intimate relationship between three people in very cramped quarters inside the car, while at the same time playing it against the broad canvas of this big Texas backdrop, with the police cars and all of that.”

I ask him quite candidly how he feels about the team he has working with him — the director and cinematographer in particular. "I'm terribly delighted with both the direction and the camerawork," Zanuck tells me. "Vilmos' work and his credits speak for themselves. I'd love to have him on every picture. And Steve is a real delight as a director. It's thrilling to see a young fellow like him have so much command and such presence. For a young man making his first theatrical feature, he's doing an exceptionally good job. He does his homework and he's well prepared — yet, when his eye sees something spontaneous on the set, he's very adaptable and very creative. I think that when this film comes out he's going to be a major director."

A few minutes later, the Panaflex camera comes up in conversation and Zanuck says: "t just think it's nothing short of sensational. I've never seen shots like those we've been seeing in dailies — 360-degree pans from inside the car with two travelling vehicles involved. It's really fantastic. I don't know that much about cameras, but I've seen a lot of film and I've never seen shots like that before. The Panaflex is just a super camera — super-efficient, super-quiet, super-small and super-light. It's perfect for this picture and we're very proud to be the first ones to use it. Bob Gottschalk, when he heard what kind of picture we were making, wanted us to use it and I think this picture will be a good showcase for the camera. Of course, everybody wants it now anyway, sight unseen. It's a great piece of equipment."

beside him. In the back, Goldie Hawn grins her famous grin. Up front is William Atherton, who plays her husband in the off-beat picture.

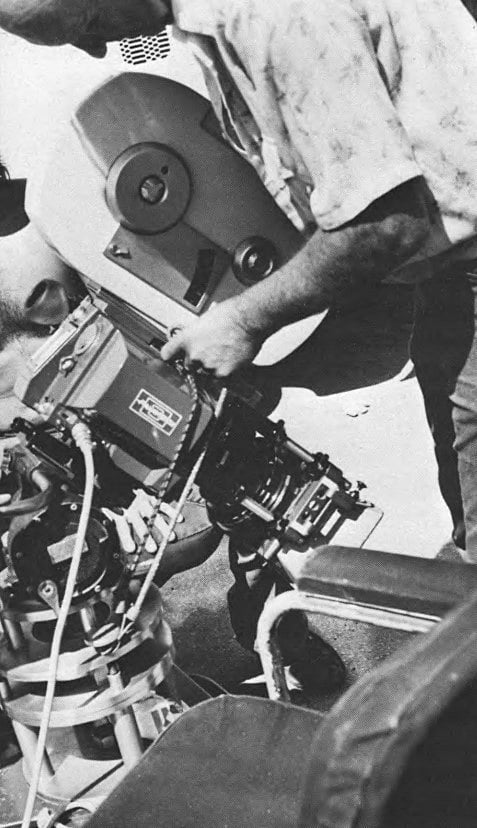

The first set-up of the day involves police car 2311 parked along the roadway on the outskirts of Floresville, with the long column of police and civilian vehicles several hundred yards away, strung out in the background. They have, according to the story, been ordered to keep their distance while the ranking law officer (Ben Johnson) gets on the radio and tries to persuade the amateur hijackers to give themselves up. This is one of the few scenes in the picture in which the car is not moving, so the Panavision R-200 camera is simply set up on tracks alongside it for a short dolly movement. Moreover, there is a chance to use a bit of fill light, so two Xenotech Sunbrutes are set up at either end of the car, shooting through sheets of plastic diffusion material.

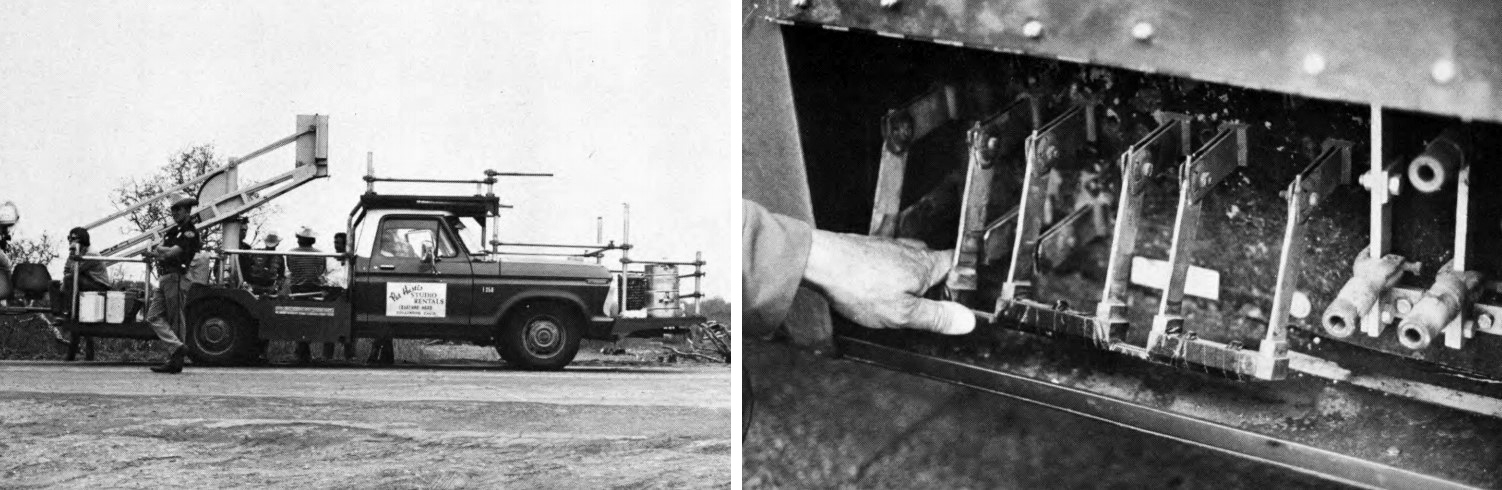

I notice that there is not a generator anywhere around and that the cables from the xenon arcs lead, instead, to a camera truck equipped with a 12' crane. The truck belongs to Pat Hustis of Hollywood, who is on hand to run it, and he tells me that it is a brand-new rig being used for the first time on The Sugarland Express.

"I should call it the 'Xenon Express' because it was basically designed to run the xenon arcs,” Hustis says. "They had been using the battery cart system, which is an excellent system, except that it is a trailer which has to be towed. Jim Blair, our gaffer on this picture, came up with the idea of incorporating the batteries right into the structure of the truck. Jim came to me and wanted to know if I could build a 36-volt, 350-amp-capacity battery system into the camera car. In that way, they would have the power supply for the xenon arcs without having to pull the battery cart — which would make for greater versatility in scenes where we're towing an automobile. So we sat down in my shop and figured it out and then made a 120-volt single-throw switch conversion to 36 volts. This makes it possible for us to run conventional lights on small sets and also provide 36 volts for the xenon lights — with all the power coming from the camera car. On this picture it's worked out exceptionally well. We've been working with a rather small crew and in quite limited work areas and we've found that about 70% of the lighting for the picture could be done from the camera car itself. A lot of the action involves anywhere from one to 140 automobiles in pursuit of the camera car and, with the aid of the xenon lights, we've been able to light 100 to 150 feet behind the camera car. These lights are also excellent when we're stuck with bright sunlight and have to fill the faces.”

I'm intrigued with what Hustis has done with his new camera car — which, incidentally, doesn't appear any larger than a conventional rig — and I ask him to tell about how and where he stashes the batteries, how long the charge lasts and what is the recharging time. "We found that when burning two xenon arcs there's about a 250-ampere-hour drain,” he says. "This means that the batteries will last for about 30 minutes of actual filming time. Into the chassis of the camera car we've built a 120-volt (or 36-volt) 250-amp DC generating system that runs off the truck engine, which allows us to recharge at almost the same rate as the current is used. All day, between shots, we keep the engine running at full charge. Then, at night, we use a stationary charging unit that we plug in at the hotel, or wherever we happen to be, and this saves the truck engine from having to run so much during the day.

"The construction of the battery pack itself presented an extremely difficult problem because, in order to have enough capacity to last us at 250 amps for 30 minutes at a time, we found that we had to use very large Trojan batteries — and space is always a problem in any kind of mobile unit. We ended up by using 96 feet of 00 cable just to connect all of the batteries together, because they're set throughout the entire vehicle and wired into a central triple pole, with a triple throw-switch that converts the current from 120 to 36 volts. Distributing the batteries throughout the vehicle is actually advantageous to the operation of the camera car, because I was able to sit down and figure out where extra weight was needed to improve ride quality. For example, on this camera car we have a crane which extends 12' and it requires 1,200 pounds of counter-balancing. By the time you get all that stuff on a camera car it suddenly becomes a truck and, without proper weight distribution, you start to lose ride quality. It took a little time and thought to figure out where to locate the batteries to counteract this effect, but we built compartments under the hood, behind the seats and in the frame rails, so that the weight distribution is just right.”

Since more and more shooting is being done on location these days — and since generators are a cumbersome, noisy drag at best — I want to know more about how this system can be used with conventional tungsten and quartz lamps.

truck's body, so that banks of lights can be run without resorting to usual battery cart. Right: Throw-switch on side of truck, which permits quick

conversion from 120 volts, for conventional lamps, to 36 volts needed to run xenon arcs. About 70% of lighting on film was run from these batteries, eliminating a noisy generator.

"No problem,” says Hustis. "We simply throw the switch to the 120-volt position and then it works the same as a conventional battery pack — and, of course, we have the 120-volt charging system built into the truck. Using 100 amps of conventional 120-volt lamps — which is what it takes to light one or two automobiles — we're good for about one-and-a-half hours of actual filming time. That's almost a full day's production. We can recharge between set-ups or at lunchtime or whenever it's convenient. Using the truck engine is, of course, noisier than using a conventional plug-in charging system, but it's not offensive. You can still work around it, although you can't actually shoot while it's running. Prior to this we had to use conventional 400-amp aircraft engines to charge the batteries between shots, but they're too noisy, a bit offensive when you're trying to sit and talk. We started construction on this car last November — a camera car with a crane — and we planned to use the aircraft-type generator, but then along came Mr. Blair with this battery idea and we put all the boys in the shop to work on it with all of our brainpower. We designed and built the system specifically for testing on this picture and it's been working perfectly.”

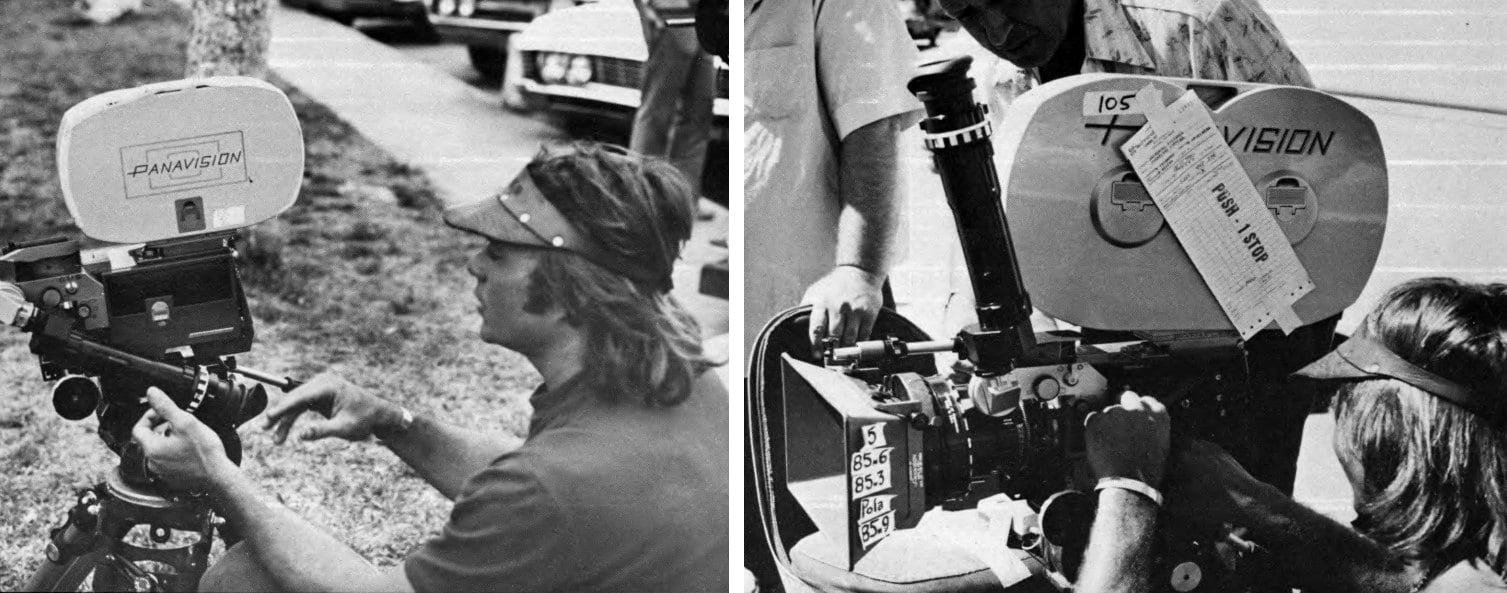

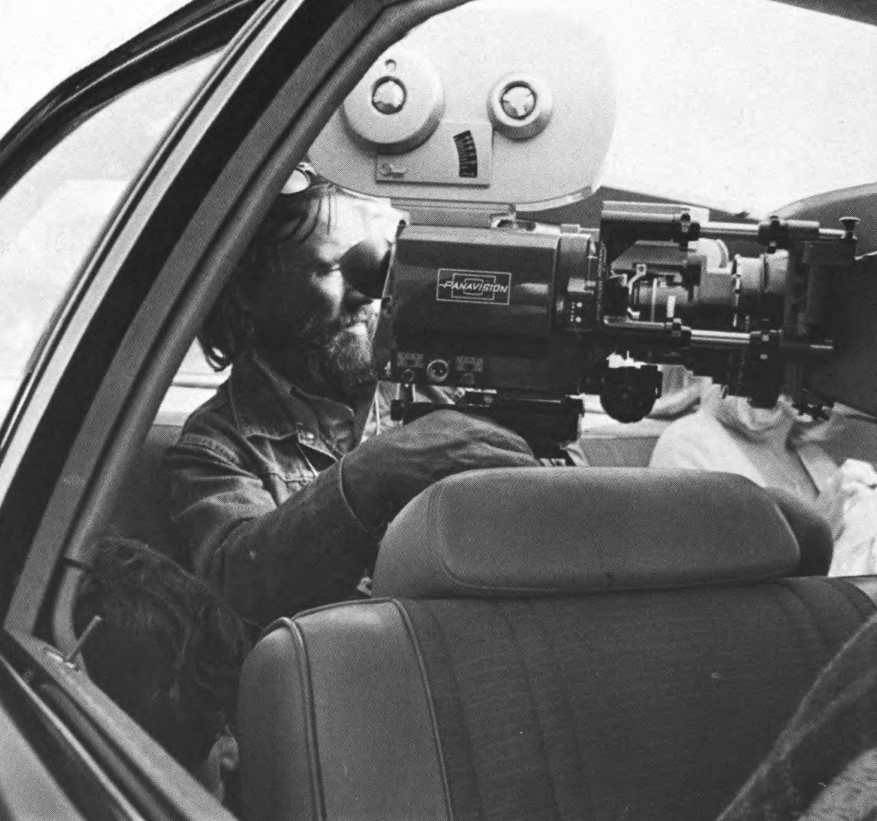

Round about mid-day, the precious, newly arrived Panaflex camera is broken out of its cases and set up. Not since the Arriflex 35BL camera was introduced during filming of the Munich Olympics have I seen a piece of equipment awaken such interest in a crew of technicians. The Panaflex is clearly the “darling” of the company. Everybody wants to pick it up, look through the lens or just pet it. They treat it as if it were a baby-ladling out great gobs of tender loving care and exercising extreme caution in handling it, even to the extent of binding shock cord around it when it's mounted on the crane "just in case.” Next to its "big brother,” the imposing Panavision R-200, the Panaflex looks almost like a toy, but it functions like the incredibly sophisticated electronic instrument that it is and everyone seems delighted with its performance.

“When I was beginning in TV I used a lot of fancy shots. Some of the compositions were very nice, but I’d usually be shooting through somebody’s armpit or angling past someone’s nose. I did a lot of that early on and got it out of my system.”

— Steven Spielberg

After a better-than-average location lunch, I find myself in conversation with Spielberg, and it runs like this:

American Cinematographer: Can you describe the visual style which you're using to put The Sugarland Express onto film?

Steven Spielberg: We've been filming this picture in a very simple direct way, without anything fancy. The action is the eccentricity of this film so Vilmos and I have been shooting it in a very straightforward manner. I remember that when I was beginning in TV I used a lot of fancy shots. Some of the compositions were very nice, but I'd usually be shooting through somebody's armpit or angling past someone's nose. I did a lot of that early on and got it out of my system. I finally became less preoccupied with mechanics and began to search more for the literary quality in the scripts I was reading. I believe I've gotten to the point where I can appreciate a good piece of material and translate it into film without my own ego showing up on the screen. I think that's what has happened on The Sugarland Express.

In terms of dramatic approach, what role does your camera assume in the telling of this story? In other words, is it predominantly objective or subjective?

We use the camera in two different ways: to represent the point of view of the Highway Patrol officers, and also the point of view of the fugitives inside the car. It's up to the audience to determine who's right or who's wrong. That's what this picture is all about. So, in that sense, I think the camera is nothing but a spectator — though Vilmos and I have let the camera editorialize when that's been necessary.

“I’d heard about this crazy Hungarian who lights with six foot-candles and who’ll try absolutely anything — so I sent the script to Vilmos and he loved it.”

— Steven Spielberg

Have you been doing anything that you feel is visually innovative in this picture?

There is one thing that I've been doing that I've never tried before and it has to do with revealing a surprise to the audience. For example, there is one sequence in which I wanted to show police car 2311 running out of gas. The captive patrolman, in a private, personal effort to stop the fugitives, notices that the gas gauge is down to "E," but he decides to ride it out and see what happens. I chose to shoot this sequence near a very large dip — about 50' deep — in a major highway. We shot it with a 1,000mm lens and, in the background, you'll see 15 police cars going into the earth behind a second horizon line that is very much in the foreground and so soft that it looks like the police cars are being eaten by the ground. Then the next thing you see, in almost startling closeup, is our car 2311 rising up out of that same foreground cutting piece. You see the three people in the car and then you hear the sound effects: sputter...sputter...sputter... The car stops ao it runs out of gas and begins to sink back down the hill. All the way through this movie I've been using the terrain as interesting discovery pieces and it's worked out just beautifully so far.

I've noticed that there seems to be a very special working rapport between you and the director of photography on this picture. What is your usual approach in selecting a cameraman to work with, and how did you happen to choose Vilmos Zsigmond to photograph this picture?

Up until now I've only worked on TV episodes and features for TV, but my usual approach to selecting a cameraman is to ask myself two questions: (1) Do I like the man personally?, and (2) How big is his ego? If his ego is too big, he's not going to want to do all the shots I want to make. He's going to give me a rough time and I'm not going to use him. But if he's the kind of guy who will experiment and try things he's never done before in his life — who will light a scene with eight foot-candles, if that's all that's available, then I'll grab him in a minute. In other words, I look for a cameraman who's not going to fight me by saying: "It can't be done." I'd seen McCabe and Mrs. Miller — which is my favorite Vilmos Zsigmond film — and Images and Deliverance and parts of The Long Goodbye, and I'd heard about this crazy Hungarian who lights with six foot-candles and who'll try absolutely anything — so I sent the script to Vilmos and he loved it. I explained to him that I wanted to shoot this whole picture in the rain with windshield wipers going all the time, and he committed to it. Well, we haven't shot in the rain during the last 47 days, but we've had other interesting weather effects and, to me, he is the biggest joy on this film. It's great when you find a cinematographer who also can function as a director's sounding board, a kind of Devil's Advocate. It's an enormous help when egos don't dash and you can creatively exchange thoughts — not on just the momentary problems, but conceptual ideas, as well. Vilmos is the kind of cameraman whom I'd invite into the cutting room, because he would have something to contribute. I would never do that with any other cameraman that I know. He's an amazing man.

“The way he directs a film makes you think that he must have many features behind him, but this is his first feature and it’s really unbelievable. I can only compare him to Orson Welles.”

— Vilmos Zsigmond

What is your opinion of the new Panaflex camera?

It took a long time getting here, but it was worth the wait. It's a sensational tool, and I think it's going to revolutionize the business. Many times, in filming for TV, I've been romanced by a shot and have sacrificed performance because I was trying to get in real close with a 20mm lens. I like very much to keep the foreground and the background exceedingly sharp, and then allow the audience to choose what is commanding attention in the scene. Anyway, because of the noise from the camera working that close to the mike, the poor actors would have to come in later and loop the whole scene. The Panaflex is so quiet that it eliminates the necessity for looping. It's especially valuable on a picture like this in which at least 60 percent of the action takes place inside a car, but you still want to get a lot of variety. The Panaflex is so small — especially with the 250' magazine — that you can do just about anything with it. It's great for shooting in close quarters. You can't get in that close with the Panavision R-200 because it's so much bigger. For weeks on this film, while waiting for the Panaflex to arrive, we've had to take the R-200 and rig it on a special dolly track mount next to the car and dolly back and forth, because I couldn't actually stick it through the car window. But you can tie the Panaflex onto a board, start it going, shish-ka-bob it through the window and into the car and then pull the board out through the opposite window. In other words, with the Panaflex you can make a "dolly'' shot straight through the guts of the car, without having to zoom from window to window. It's an amazing camera and I'm sure Mr. Gottschalk is very proud of it. The only sad thing is that it's late — about 20 years late.

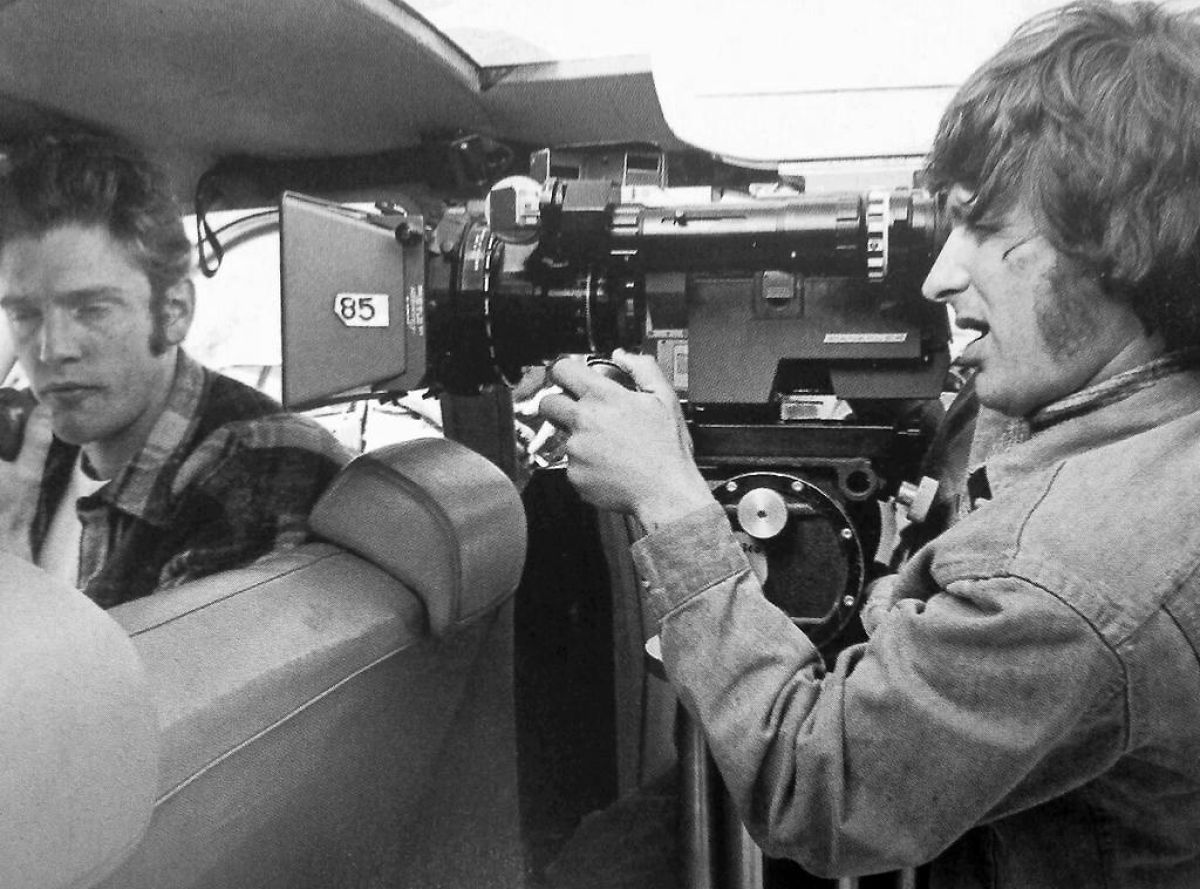

That evening, in the projection room set up in the hotel, dailies are screened and I get my first chance to see what the Panaflex has been able to do in action. The results, especially the scenes shot inside the car while it is traveling, are nothing short of incredible. One in particular sticks in the mind. The operator, obviously riding in the back seat, starts on the husband and captive policeman in the front seat. It pans around to show Goldie Hawn in the back seat, then continues around so that we can see through the rear window that Ben Johnson, in another police car, is rapidly gaining on them. The camera pans front again as Johnson draws abreast on the left side. There is an exchange of dialogue between the two drivers. Then Goldie sticks a shotgun out of her window and, in ladylike tones, tells Johnson that if he doesn't get the hell out of there she'll blow his bloody head off. He falls back and the camera pans to the rear with him. A moment later, in the same shot, he draws up on the opposite (right) side of the car and there is another exchange of dialogue before the lead car pulls away from him and the camera settles on the men in the front seat. In the meantime, the Operator, probably tied in a pretzel by now, has covered a panning arc of at least 480 degrees in the one shot. It is the kind of shot one could visualize being made only by a dwarf contortionist handholding something like an Eyemo — but here it all is on the screen, with usable sync dialogue, yet.

Dick Zanuck leans over to me and says, “Incredible! There's never been a shot like that on the screen before.” I'm willing to bet that he's right.

“When you are working with what is essentially a caravan — as we are all the way through this picture — it could become very stagnant if you just kept cutting from close shots to long shots, so we’ve kept the camera moving but, at the same time, we’ve managed to disguise the moves, and that has given the film an interesting look.”

— Steven Spielberg

What is so impressive about these dailies is that, while the camera does some impossible things, it never calls attention to itself. There are no tricks for the sake of tricks. Even the zooms are so skillfully orchestrated that they are covered by the action and remain totally unobtrusive. When I later mention this to Spielberg, he says, "Vilmos is the only cameraman I know who thinks like me in terms of lateral dolly moves and in terms of hiding the zoom. I hate to see unmotivated zoom shots, and I see them so often on TV — zoom in, zoom out! Vilmos feels the same way about it, so we disguise all of our zoom shots. You don't notice that the camera has gone from close to far. By the time you would normally become conscious of the zoom a cut has been made and you are only faintly aware that the scene has assumed a different look. When you are working with what is essentially a caravan — as we are all the way through this picture — it could become very stagnant if you just kept cutting from close shots to long shots, so we've kept the camera moving but, at the same time, we've managed to disguise the moves, and that has given the film an interesting look."

The next morning, crack of dawn, we drive out to beautiful downtown Floresville, where the “big” sequence of the picture is to be filmed. By this time, according to the script, the fugitive car has acquired a caravan of followers, including hundreds of admiring fans (all on wheels) and sixty or seventy police cars from various headquarters. The caravan inches its way down the main drag, as the entire town turns out to stage their bucolic version of a royal welcome. The fully uniformed high-school band (complete with majorettes) is tooting away, trying to get it all together. Mounted Shriners, togged out in their ritual finery, fight desperately to control their nervous horses. A country-western band on a flatbed truck is banging out rhythms never heard on this planet before. A miniature ferris wheel, set up in the street, rides the kiddies dizzy. Cold pop and cotton candy vendors are doing a brisk business. It appears that all 3,710 of Floresville's residents, plus dogs and cats, are on hand to join the fun — truly a sight to delight the heart. One wide-eyed young thing, practically orgasmic with glee, sighs: “This is the most exciting day of my life!”

necessary to give a "bird's-eye view" of the happening. Right: How the scene looked from camera position. All 3,710 of Floresville's citizens

seemed to have turned out to be in the movie.

In the midst of the chaos, a huge Chapman crane has appeared on the scene and taken up station at one end of the main street. The Panaflex is broken out and mounted on the end of the boom, with a grip tying shock cord around it “just in case.”

Then the fun begins. The high school band, in a flourish of sour notes, begins to play. The majorettes begin to twirl. The crane starts to move down the street through the crowds, booming up as it goes. The diminutive Panaflex looks a bit ridiculous perched on the end of that huge boom, but it's getting the picture. At the far end of the street the crane booms down to embrace the Western band, by now in a lather of country rock. It's mind-boggling!

After eight or ten takes, cutaway shots are made, point-of-view shots from inside a bar out toward the street, and quick cuts in the town square where people are hanging from the tower windows of the courthouse and climbing trees to catch the action. Both the Panaflex and its "big brother,” the Panavision R-200, are burning film like crazy.

“Most of the action — 50% or more — takes place inside a car and we have a young director who really wants to do the impossible. He wants to shoot the car from all angles at the same time.”

— Vilmos Zsigmond

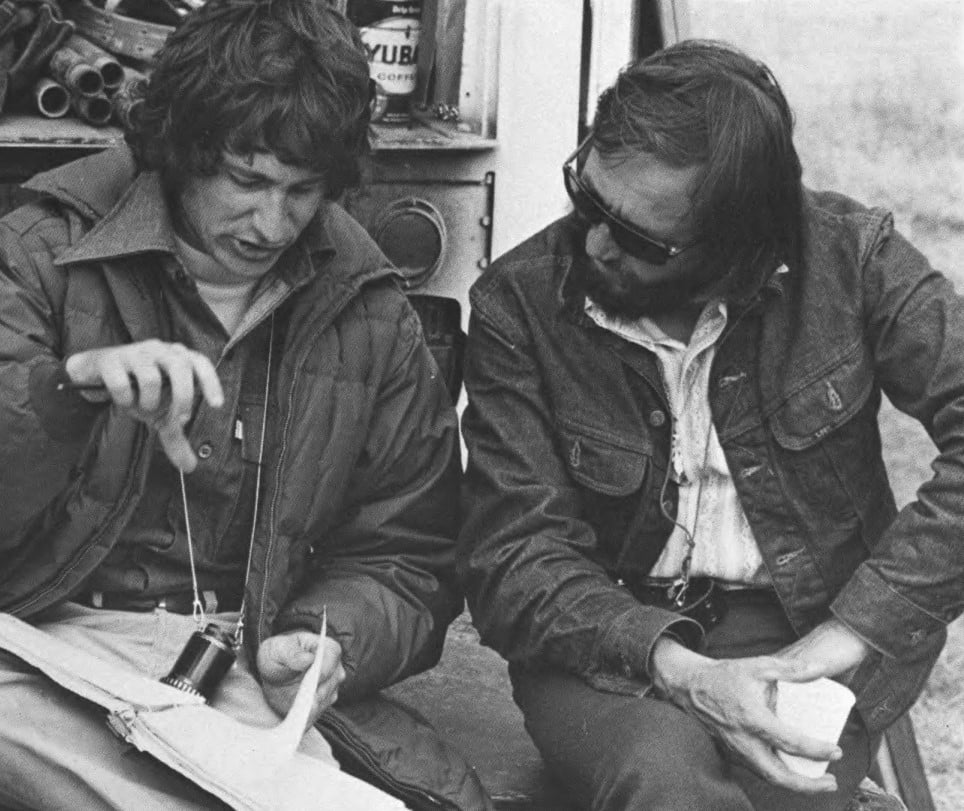

Later, back at the hotel, Zsigmond and I have a chance to talk and the talk goes something like this:

American Cinematographer: Can you tell me a bit about the general photographic style you're using on this picture?

Vilmos Zsigmond: Well, we aren't really going for a definite style on this picture. What we're going for is reality. We just want to photograph the action as real as it looks. We would like the audience to feel that they're with us every single minute — inside of the car, outside of the car, everyplace — and we would really like not to be noticed at all. That means that we're trying to avoid lighting the film. We're trying to make it look as though there're no cameras and no lighting involved at all. I tried to do the same thing on Deliverance and most of the time it worked, but I think this is going to be even more "real'' than Deliverance.

What are some of the unique challenges of this picture?

Most of the action — 50% or more — takes place inside a car and we have a young director who really wants to do the impossible. He wants to shoot the car from all angles at the same time. Many times he'll come up with an idea and he'll ask: "What would happen if you put a camera inside in the middle of the car and pan around 360 degrees?" The funny thing is that when we do the shot it turns out to be 480 degrees. Obviously, if you think about the problem, you will realize that we can't use any lights at all inside the car. We're making a pan all the way around and there's no place to put lights. Another problem is how to record detail in the faces without burning up detail of what's outside the car. You don't want the outside so overexposed that you can't see anything, but at the same time, you want to see the faces of the actors inside the car. Obviously, you cannot accept a silhouette.

“If we had shot with an ordinary camera, the scenes would have had to be looped. We tried to shoot inside the car with the R-200, but we just couldn’t get the camera set in the right places.”

— Vilmos Zsigmond

I'll bite. How are you managing it?

Technically, the only thing that helps me here is the technique we've developed for flashing the film. We've experimented with it on previous films [including The Long Goodbye] and found that it works. Many times, on this picture, it's sunny outside the car and there is so much contrast that the only way I can help the situation is by flashing the film more than usual. Quite often we're using as much as 20% to 25% flashing, but it's been working fine. You see the detail in the faces, as well as the detail outside. What we're really doing is altering the characteristics of the film in order to handle this very contrasty kind of situation.

Does that mean that you haven't been using any lights at all inside the car?

Let's put it this way: If we're in a situation where we can't use lights, then we don't use lights. But if we're doing shots where we don't move around, or where the car is stopped, then we do help the faces by using some lights and I can cut down a little on the flashing, because flashing is not really an answer for everything. I mean, whenever I can I will try to get the best result. The problem is how to blend that scene in with the others so that it doesn't look like a jump. You really have to be very careful how you do it. Even when we do light, we under-light the scenes. We're pushing the whole picture one stop in processing.

I can see how flashing would help expose the detail in the faces, but what about the exterior background outside the car. It's already so bright that there would seem to be a danger of really burning up those areas of the scene. Isn't that so?

The interesting thing about flashing is that it really affects just the shadow areas. Let's think about the lighting ratios. Let's think of the places where the sun lights up a face, and we'll call that 100% lighting. The shadowy part, which catches some reflected light from the sky, has only 5% lighting. Now we are dealing with a ratio of 20-to-1. If you add 10% flashing to this, it really means that you are adding 10% more light to both sides of the face—the lighted area, as well as the shadow area. Now the original 100% becomes 110% and the 5% becomes 15% — so your ratio changes to something like 8-to-1, which is a ratio that the film can handle. It would not have been able to handle the 20-to-1 ratio. It's really like adding fill light. You use lights whenever you can, and when you can't use lights you use flashing.

"handheld" by Zsigmond, with a little help from his friends. This photograph was sent to Panavision President Robert Gottschalk to help speed the arrival of real Panaflex unit.

You are the first cinematographer to use a production model of the Panaflex on a feature. What are your impressions of it?

I think it's fantastic. It's like you dreamed about a camera with which you could do everything, and with this camera, I think, you can do everything. We've waited a long time for the Panaflex to arrive and we postponed shooting some scenes until then, so that we could shoot with sound inside the car. If we had shot with an ordinary camera, the scenes would have had to be looped. We tried to shoot inside the car with the R-200, but we just couldn't get the camera set in the right places. After six weeks of waiting, we got the Panaflex and jumped right into shooting scenes with it. The results have been fantastic. One of the beautiful things about it is that you can mount the magazine in two positions — on the top or at the end. Most of the time, when shooting in the car, you have to mount the magazine at the end of the camera in order to get enough head clearance. You can also shoot through the windows and be high enough to see outside. I don't think there's any other camera that can do this.

“Most young directors, when they get their first film, somehow get timid; they pull back; they try to play it safe, because they are afraid that they will never get another chance to make a feature. Not Steve.”

— Vilmos Zsigmond

What are your reactions to working with this new young director?

Spielberg is probably the most talented director I've worked with. He's only 25 years old, but he seems to have had the experience of a man 40 years old. The way he directs a film makes you think that he must have many features behind him, but this is his first feature and it's really unbelievable. I can only compare him to Orson Welles, who was a very talented director when he was very young. There's one great thing about him that I like very much. Most young directors, when they get their first film, somehow get timid; they pull back; they try to play it safe, because they are afraid that they will never get another chance to make a feature. Not Steve. He really gets right into the middle. He really tries to do the craziest things. Most of the shots he gets he could only dream about doing, up until now. He could never do them on TV. He did a TV feature called Duel and it was magnificent, but he couldn't experiment much on that one. On this picture — where he has a nine-week schedule — he's really trying to fulfill his dreams. As a cameraman, I think the best thing I can do for him is to really try to get the shots he wants. I never try to talk him out of a shot, even if what he wants to do seems impossible. Occasionally, we just cannot do a certain shot he's dreamed about and I really feel badly, because I always feel, along with him, that there must have been a way to do that shot. But 90% of the time we succeed, because we both want to do the shot. Some of the people on the crew may laugh at us when we're going through the rehearsals and all that insanity, but, in the end, when we've got it, they seem pleased that we did something that seemed impossible to do.

Spielberg and Zsigmond again collaborated on the science-fiction fantasy Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), for which the cinematographer earned the Academy Award. The director was honored with the ASC Board of Governors Award in 1994. The cinematographer was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 1999 and died in 2016.