A Transcendent Career Foretold: Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC

The American Society of Cinematographers honors Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC with their 1998 Lifetime Achievement Award.

This article originally appeared in AC Feb. 1999. Some images are additional or alternate.

A fine art gallery in Los Angeles recently featured an extraordinary display of still photographs taken by Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC. The shots included a compelling self-portrait taken nearly 50 years ago in an empty field near Szeged, Hungary, where Zsigmond was born and raised during the Nazi and Soviet occupations of his homeland. Five decades later, he explains his pensive stare: “A gypsy [fortune-teller] told me I was destined to sail on a ship across a great ocean to a big city, where I’d become an important artist.”

“My rule is that if a movie doesn’t say something of value for the audience, I don’t think it’s worth making. You only have time to make so many pictures in your life.”

It was a tantalizing prediction because fortune-tellers were taken seriously in Szeged, but the notion puzzled Zsigmond, who had no experience with freedom. He couldn’t even visit the next village without permission from the commissars, so Zsigmond didn’t understand how he could sail across a great ocean and become an “important artist.”

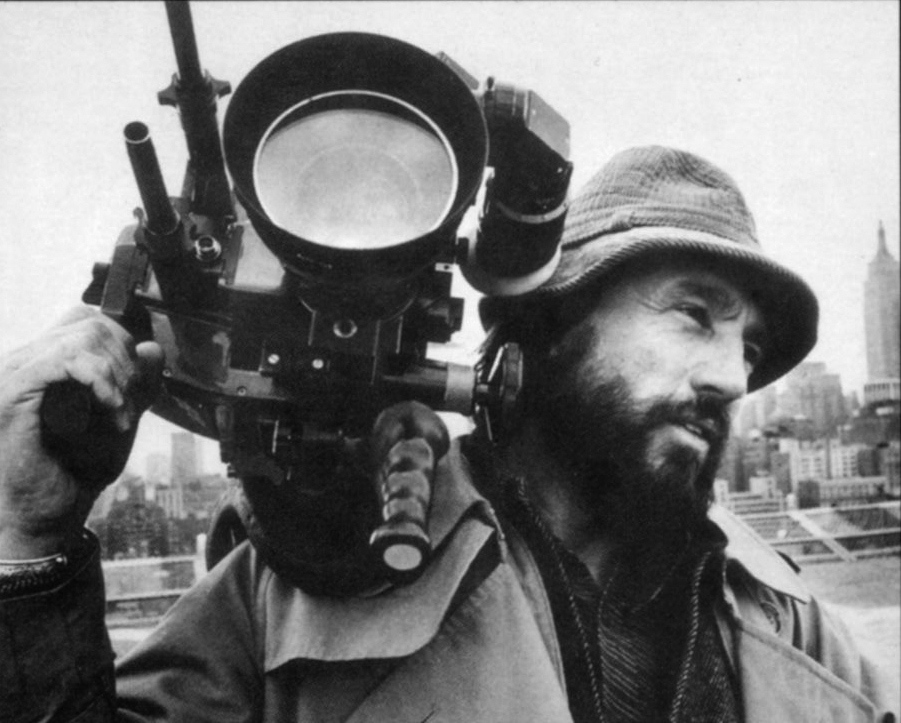

Yet within a few years, Zsigmond did cross the Atlantic Ocean and eventually made his way to Los Angeles, where he overcame seemingly impossible odds to become an influential cinematographer in the evolving art of filmmaking. His body of work currently consists of nearly 60 features, including such diverse pictures as McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Deliverance, Cinderella Liberty, The Long Goodbye, The Sugarland Express, The Witches of Eastwick, Maverick, The Rose and The Ghost and the Darkness.

Considering this, it is no surprise that Zsigmond will become the 12th recipient of the American Society of Cinematographers’ Lifetime Achievement Award, which will be presented to him at the Society’s 13th annual ASC Outstanding Achievement Awards program, to be held at the Century Plaza Hotel in Century City on February 21.

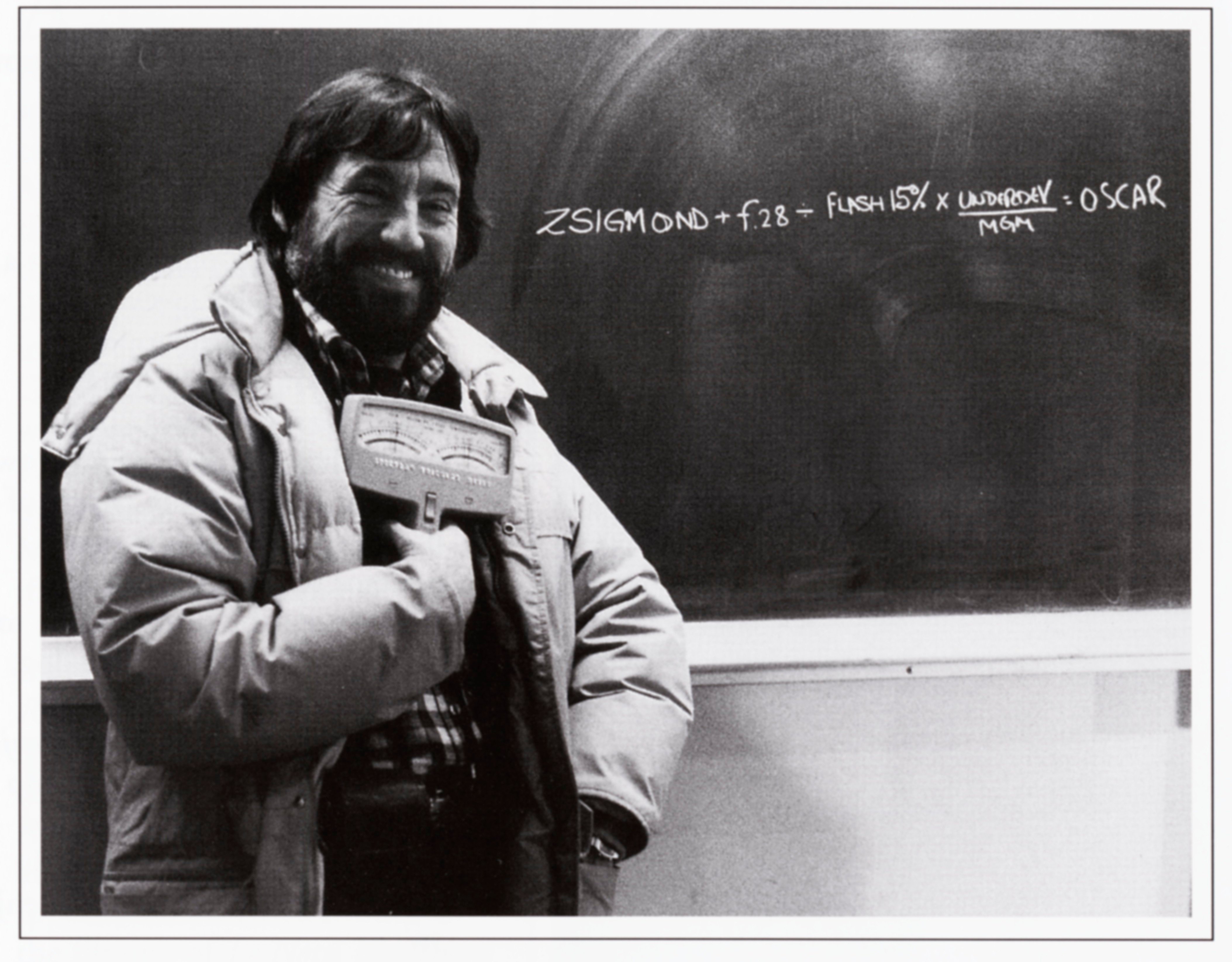

However, this is not the first time that the cameraman has been recognized for his fine work. In 1977, Zsigmond earned an Academy Award for his stellar photography in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (AC Jan. 1978), and was later nominated for both The Deer Hunter (1978, for which he also won the BAFTA Award) and The River (1984). He earned an Emmy and an ASC Award in 1992 for his extraordinary camera work on the HBO miniseries Stalin (AC May ’93). Zsigmond was then presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award at Camerlmage ’97, the International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography, held annually in Torun, Poland (AC April ’98). Despite these and many other accolades, however, he is quick to maintain that the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award represents the pinnacle of his career because the tribute comes from his peers and recognizes his entire body of work.

An innovator in his field, Zsigmond has frequently abandoned conventional thinking in favor of exploring unmapped territory. In McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1970), he “pre-flashed” the camera film to alter the contrast ratio, achieving what would become a widely emulated period look.

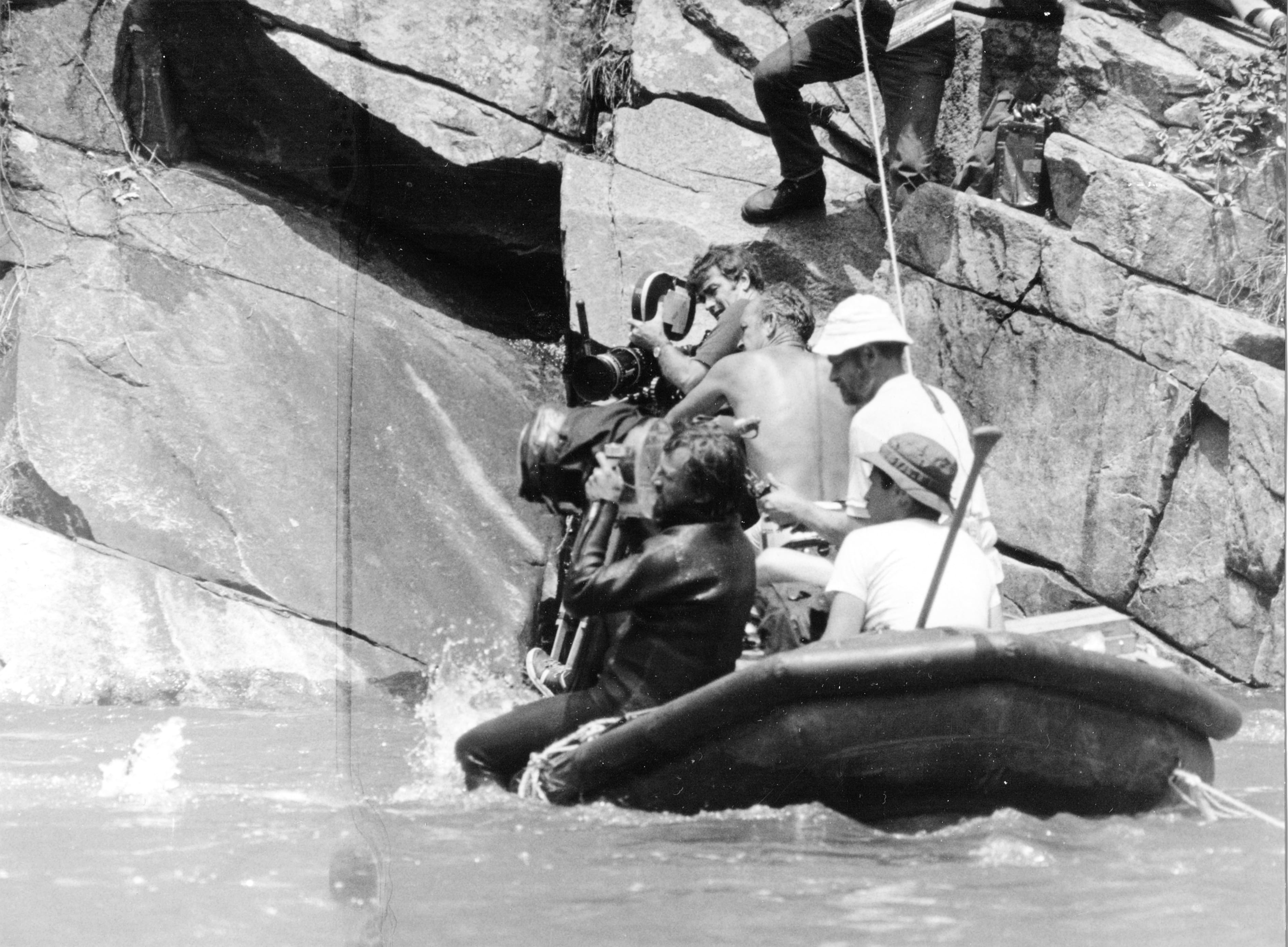

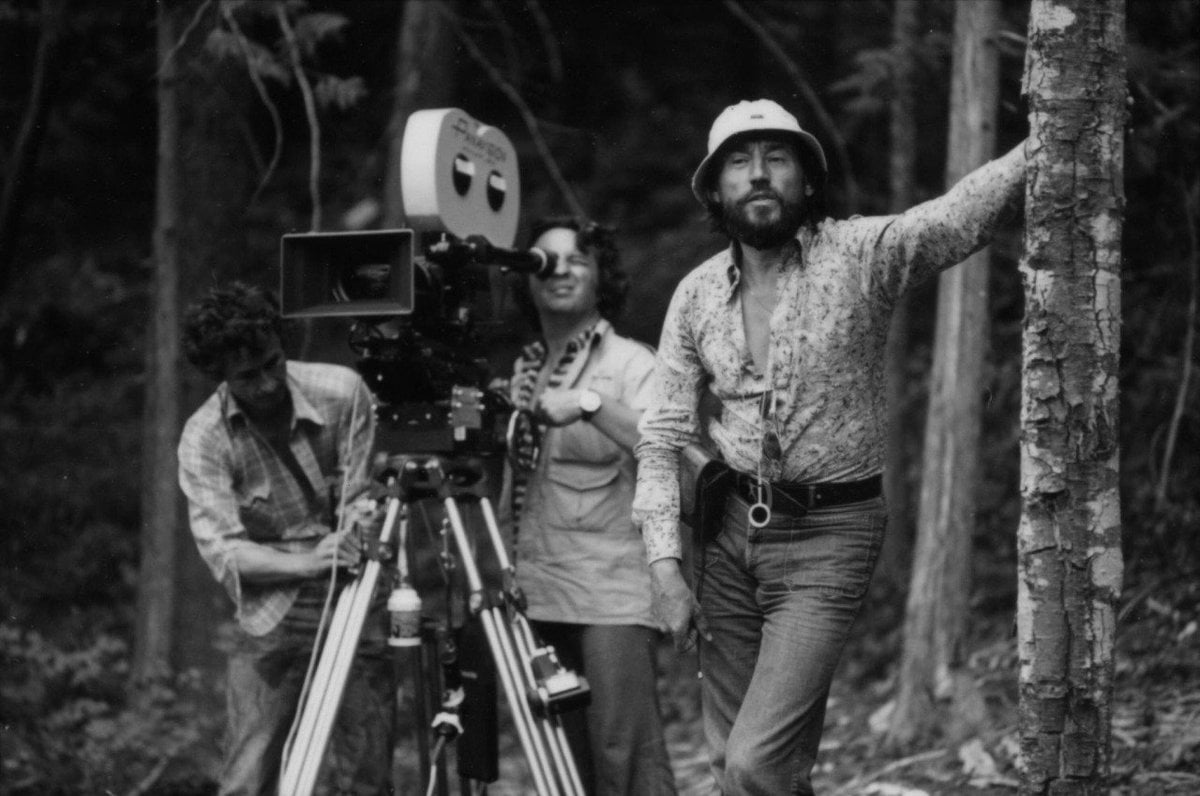

While filming Deliverance (AC Aug. 1971), Zsigmond and director John Boorman discussed whether they should shoot an important scene of the villains arriving in a canoe with a static or mobile camera. They decided that a camera on a tripod with a long lens made the tension more tactile. Zsigmond put a fluid head on the tripod and covered the camera with a plastic bag. The lens was only three or four inches above water level, recording the scene from a chillingly subjective perspective. The images provoked a premonition of primal terror; no dialogue was needed to announce that danger was approaching.

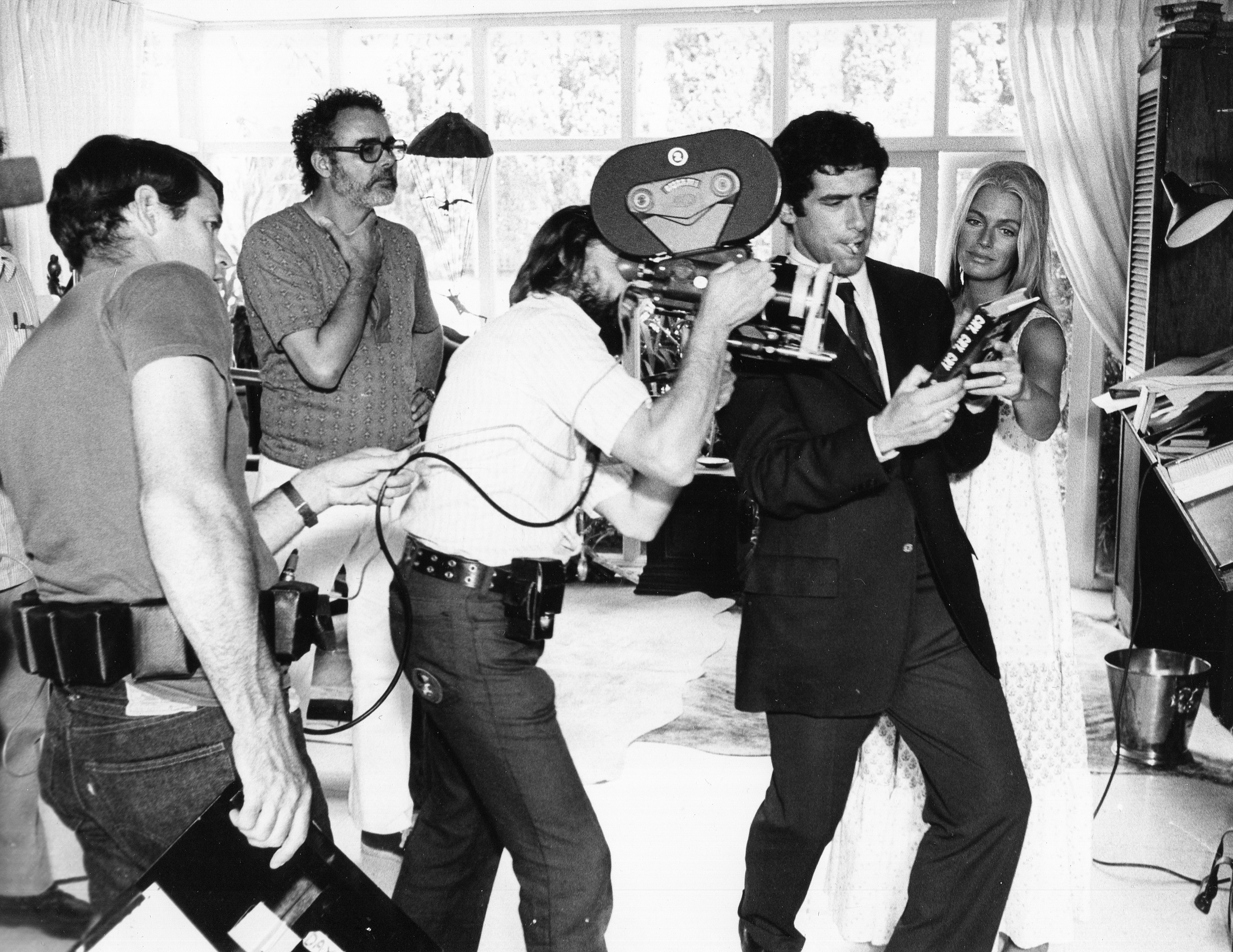

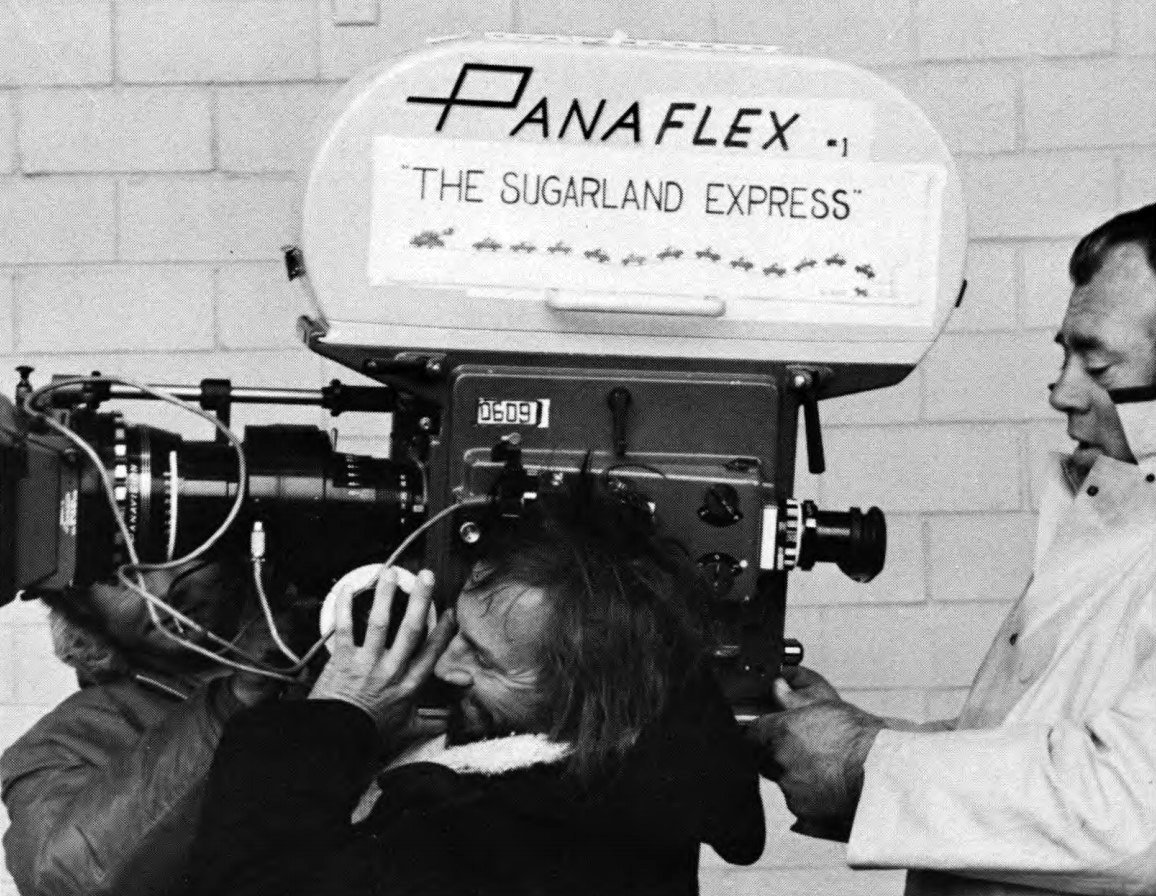

When Zsigmond was filming The Sugarland Express (AC May ’73) with director Steven Spielberg, he convinced Panavision founder Robert Gottschalk to personally deliver the first Panaflex camera to him on location in Texas. Zsigmond immediately put the camera on his shoulder and got into the back seat of a car. He pulled the audience deeper into the story by showing breathtaking action from the perspective of a passenger. “Steven wanted to direct sound in conjunction with the images,” Zsigmond says. “I needed a portable sound camera with reflex viewing that I could put on my shoulder.”

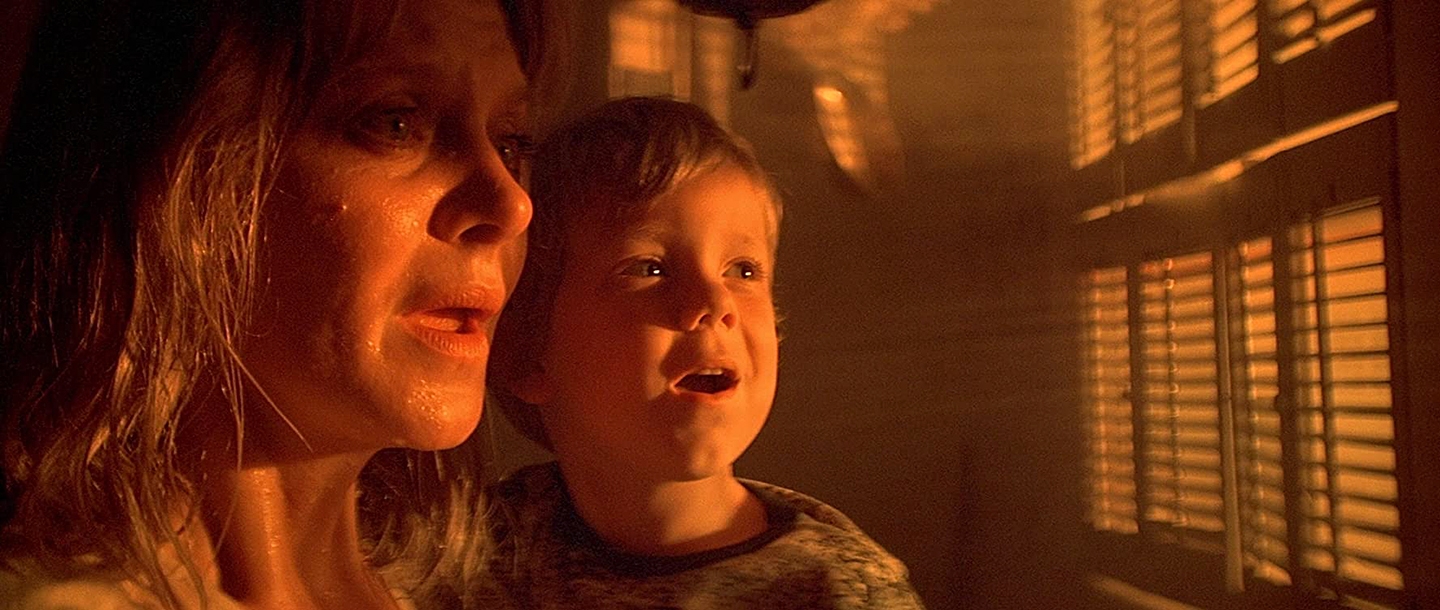

The River (AC Nov. ’84) opens with a nearly four-minute scene, which starts with a drop of rain that turns into a sprinkle and finally a torrent. The camera discovers the Garvey family in a desperate struggle to save their farm and, ultimately, their lives. Before a word of dialogue is spoken, the audience gains deep insights into the main characters. “I was lucky,” Zsigmond says. “I was working with a visually oriented director, Mark Rydell, who believed in telling stories with images. Dialogue should be like music. You should be able to follow the story even if it is turned down.”

Later in the film, there is a powerful scene in which an ominous shadow crawls across the floor of a barn where Mae Garvey (Sissy Spacek) is desperately nursing a dying calf. The shadow is motivated by rays of light from the setting sun poking through spaces in the wall. The moving shadow defines the mood, acting as a silent witness to a harsh reality.

Zsigmond describes The Rose, also directed by Rydell, as “basically a light show. We wanted to re-create an era of rock 'n roll concerts. The picture looked like documentaries of Janis Joplin concerts. We wanted the audience to see everything; nothing was hidden. That’s how we made it intimate. The singer [Bette Midler] was vulnerable. That’s why the audience loved her.”

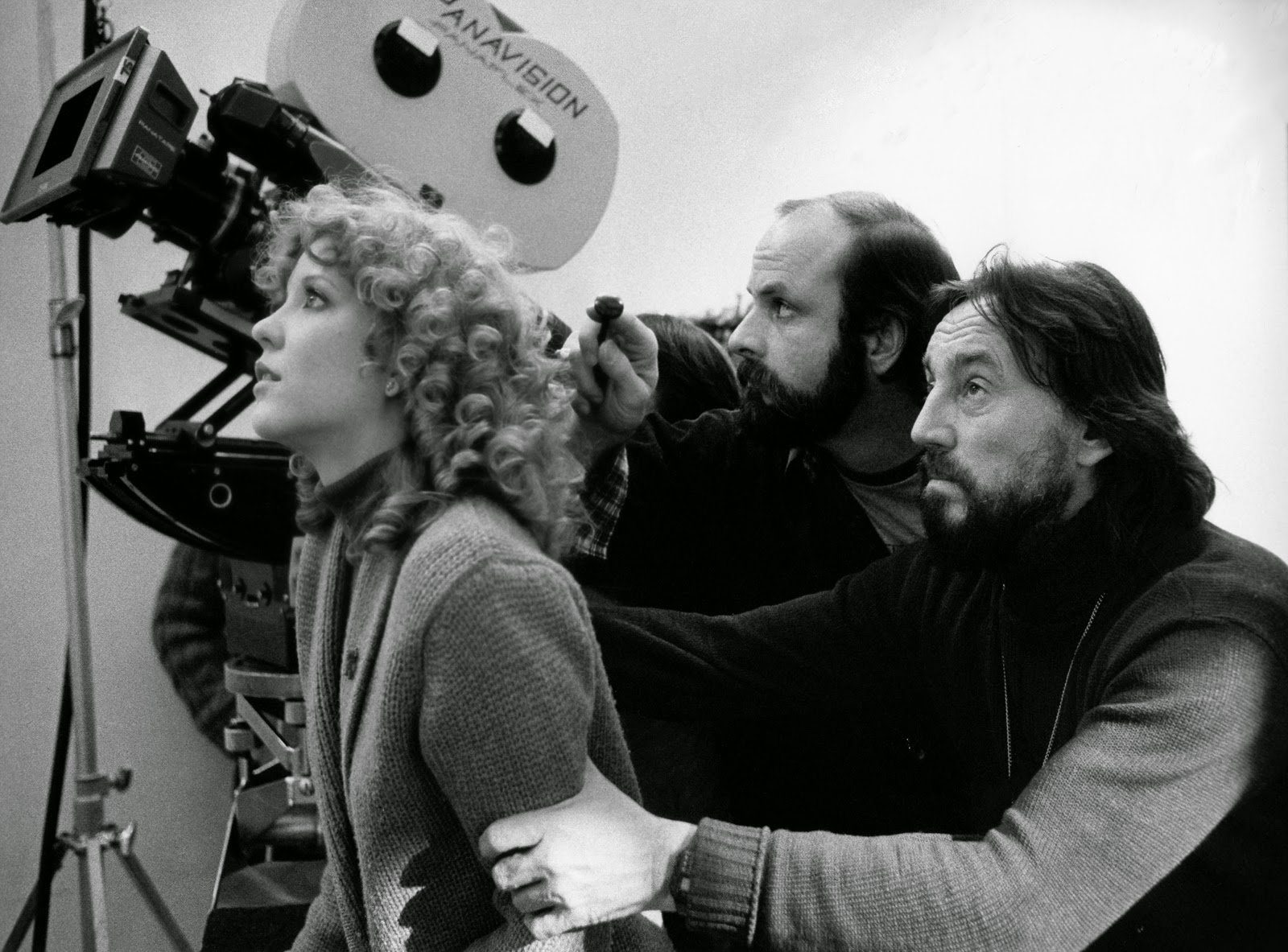

In The Witches of Eastwick, Zsigmond used colors to create a romantic and slightly surrealistic look. Jack Nicholson portrays the devil, who sets up house with three beautiful witches. Zsigmond manipulated color temperatures with the use of gels to bathe the devil in reddish tones, which were always motivated by identifiable sources. He contrasted those tones with cool, blue lighting that provided a visual signature for the witches.

In The Deer Hunter (AC Oct. ’78), Zsigmond mixed smoke with hot, red light (motivated by steel mill furnaces) to create a hazy environment that made the characters seem heroic. He explains that director Michael Cimino wanted the men in the story to seem both manly and believable. “You can see in the close-ups that it was hard, hot work, but the mill wasn’t depicted as a dehumanizing environment,” Zsigmond says. “If Michael improvised in staging, I picked it up and took his ideas a little bit further. Ideas bounced back and forth between us. It was like playing jazz music together. I love working with directors who see things visually and tell stories with images. I don’t want to discount literary values — that’s important — but first, I think, the visual part has to be there. If you want dialogue, you should read a book.”

Zsigmond traces his interest in photography to a childhood illness. When he was 17 years old, Zsigmond was confined to bed for three months, and he read a book called The Art of Light by Eugene Dulovits. Zsigmond was fascinated by the concepts it presented, particularly the use of diffusion to alter the quality of light.

Although it wasn’t apparent at the time, the book became the first step of a long journey. Zsigmond wanted to study engineering, but he was denied that opportunity because his family was considered bourgeois. His father coached a soccer team, and his mother managed a pub. In communist Hungary, people who owned anything were considered exploiters.

Zsigmond was disappointed, but not defeated. He saved enough money to buy a still camera, and taught himself how to take pictures. Soon thereafter, he organized a camera club and taught other workers how to take pictures. That impressed local authorities, who decided to send Zsigmond to the Academy for Theater and Film Art in Budapest to study cinematography. “The understanding was that after graduation, I would return to the factory to teach the other workers how to make movies,” he recalls.

Zsigmond spent four years at film school, putting in many 14-hour days and six-day weeks. While he deplored living under the tyranny of the communist government, he learned some great truths from the head of the department, György Illés, and other faculty members. “They taught us that a movie is only art if it has something important to say,” Zsigmond recalls. “It should be more than entertainment. It should have social value.” After completing his formal education, Zsigmond spent the year 1955 working as an assistant cameraman and operator at the state’s film studio in Budapest.

In 1956, a popular uprising swept through the streets of the city. For a while, it looked as if the reformers would succeed in installing a more democratic government. Zsigmond and Laszlo Kovacs, ASC, also a student at the film school, witnessed the conflict and decided it wasn’t right to be bystanders. After borrowing a motion picture camera and a generous supply of film from the school, they hid the camera in a shopping bag and documented acts of bravery and desperation, including civilians attacking tanks with their bare hands and homemade weapons.

When the Soviet army crushed the revolt, Kovacs and Zsigmond holed up in an apartment waiting to see what would happen. Within a couple of days, Illés warned them that intellectuals were being arrested. Zsigmond and Kovacs decided it was time to leave. “The Russians were saying that the revolt was influenced by foreigners and staged by counter-revolutionaries,” Zsigmond says. “We wanted the truth to come out.”

The two friends made a run for the Austrian border, carrying laundry bags stuffed with some 30,000 feet of film. They finally reached a village near the border, where Hungary was separated from Austria by a river. A Soviet patrol was in the village, and Zsigmond and Kovacs decided that the danger of being found by the soldiers was too great. They hid the film in a stack of corn in a field and walked into the village, pretending to be local peasants. The Soviet soldiers searched and questioned everyone, but none of the villagers gave away the fugitives’ true identities. The young men from Budapest soon found themselves facing a wall with their hands stretched high above them, waiting for the colonel who was heading the interrogation.

Suddenly, Kovacs remembered that he had hidden still pictures of the uprising in his boot. To this day, Zsigmond and Kovacs don’t know if the soldier overlooked the photos or simply decided to let them go. Later that night, they retrieved the film from the field, and a Hungarian border guard rowed them across the river to Austria.

A lab in Vienna processed their film, but none of the Western TV networks were interested in buying it; as far as they were concerned, the revolution was old news. The duo eventually sold the film for enough money to pay the lab bill. Later, they heard that their footage had been sold to CBS Television for $100,000. It aired for the first time five years later in a famous documentary narrated by Walter Cronkite and has since been shown many times.

Zsigmond migrated to the United States in January of 1957 as a political refugee. He spent a month in a refugee camp in New York and then moved to Chicago, where he was sponsored by the Lutheran Church. “The weather was brutally cold, and one of the other refugees, Joseph Zsuffa, a documentarian and novelist, was working on a script for a short film,” he recalls. “Joseph spoke and wrote English. I moved to Los Angeles with him in 1958, certain that I would shoot his film. I always believed I would become a cinematographer in Hollywood.”

After arriving in L.A., Zsigmond got a job in a laboratory, where he processed color film and made black-and-white prints for professional still photographers. He says he learned to speak English “one word at a time.” Zsigmond worked weekends and nights for producers who were making educational and training films.

It took him about five years to find work in the motion picture industry. His first projects were “B” films for drive-ins. They were usually filmed in 16mm Techniscope and blown up to 35mm CinemaScope. “I owned a 16mm Arriflex camera and lenses, which I modified for Techniscope,” Zsigmond recalls. “I also owned lights. Everything I had fit into a station wagon. For $100 a day, you got my equipment and my services as a cinematographer.”

“The most important thing about cinematography is lighting. That’s how you create the mood that matches the story. The ability to light artistically is a gift from the gods.”

By the early 1960s, Zsigmond had found a niche in the TV commercial industry with Gus Jekel, a cutting-edge director who owned a company called Film Fair. His timing could not have been better, because TV commercials were transitioning from hard to soft-sell, and talented cinematographers were generally given time and gear to craft “looks.” These directors of photography included such ASC greats as Haskell Wexler, Conrad Hall, and William Fraker, who helped popularize a more interpretative form of filmmaking by using soft light, long lenses and combinations of filters. Zsigmond discovered that small nuances could make a big difference in the emotional impact of a TV commercial. “I think it was really the return of an old look,” Zsigmond says. “Chaplin’s cinematographer used soft light until the studios went to a more stylized hard light. The commercial directors wanted a more natural, softer look. Kodak helped because around that time they were coming out with more sensitive films.

“Haskell [Wexler] was the first ‘Hollywood’ cameraman who noticed my work,” Zsigmond says. “I shot a movie called Futz! [in 1969], and it got terrible reviews. The audiences hated it, but Haskell contacted me and told me the photography was good. He was very encouraging, which was important to me.”

A few years later, Zsigmond got another type of support from Harry Wolf, who served several terms as ASC president. “Harry took an interest in me and gave me honest advice,” Zsigmond says. “After one film I did, he told me that my work was too slick, and I really appreciated that. Everyone needs somebody who is willing to tell them the truth; otherwise, you never get better. Cinematographers are interesting people because there generally are no secrets or jealousies. I think it is the same with musicians and painters.

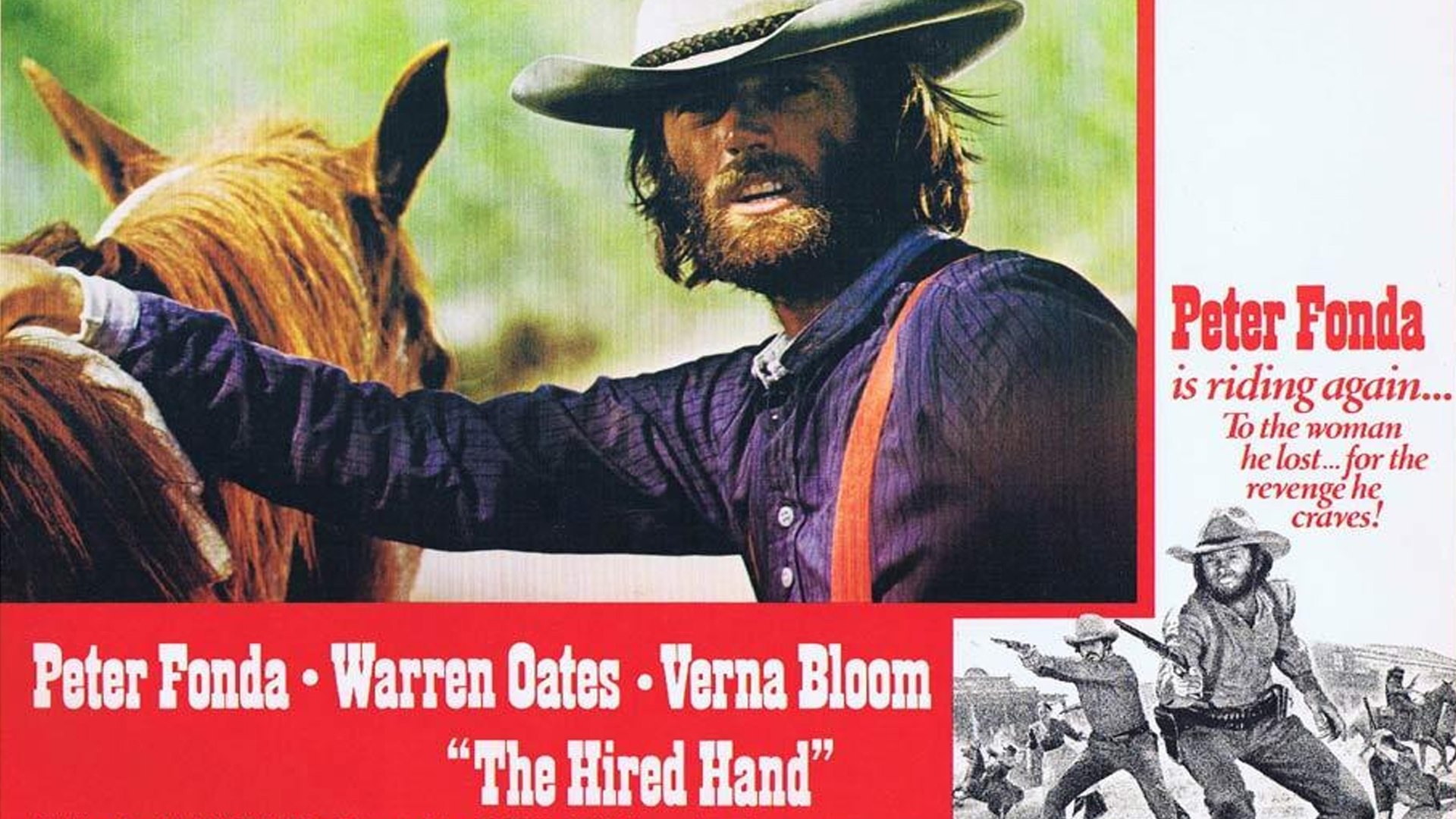

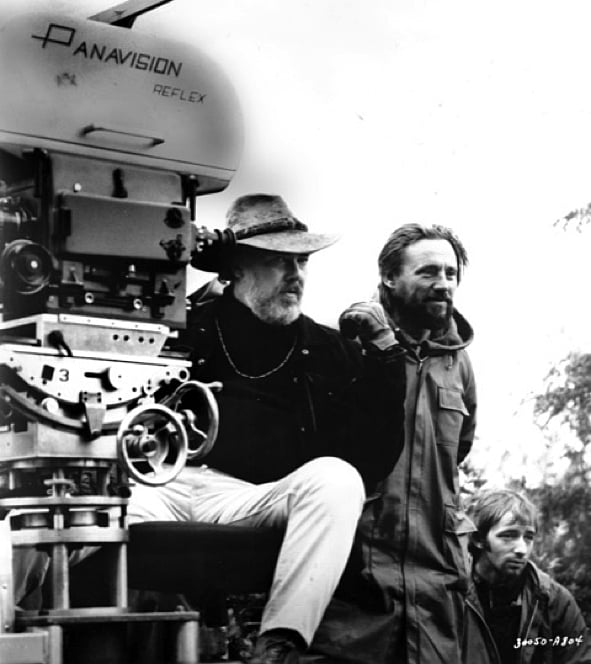

Zsigmond shot his first mainstream Hollywood feature, The Hired Hand, for Peter Fonda in 1971. That same year, Robert Altman was interested in having Zsigmond shoot McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Altman asked to see some of the cinematographer’s work, so Zsigmond showed him Prelude, a short film he’d shot for actor/director John Astin.

Fortunately, Altman liked what he saw, because Zsigmond had nothing else to show him. The Hired Hand wasn’t cut yet, and he was still shooting Red Sky at Morning — at that stage of his career, he considered those films to be the best he’d shot. “[Altman] created an incredible mood,” Zsigmond recalls, “and a big part of it was that he surrounded himself with great actors. None of them were big-name stars at that time. We had extras living in houses and tepees that we’d built as sets. They did their own cooking and bathed in the bathhouse we built for the movie. There was a still which was a prop in the movie, and they used it to make real moonshine.”

After McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Zsigmond graduated to shooting medium-budget movies, including Brian DePalma’s Obsession. “We shot that picture for $800,000,” he recalls. “I did it for a percentage of the profits, and that’s the only movie where I ever made money when my salary was based on profits. It was really fun making those movies in the 1970s, because it was very a experimental time and the directors had tremendous freedom. It was their movie.”

Zsigmond made his biggest breakthrough on Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (AC Jan. ’78). He recalls that when he heard his name announced as the winner’s at the Academy Awards ceremony, he felt as if electricity was shooting through his body. “It was like a dream,” Zsigmond says. “I still remember walking up those steps, knowing that 80 million people were watching on television. It was the first time I felt that I belonged.”

Zsigmond received his Oscar almost 20 years to the day after he arrived in the United States. He didn’t forget his past as he stood at the podium, thanking György Illés and the other teachers at the Hungarian school who gave him his start.

During the past decade, Zsigmond has photographed a number of films with blue-chip directors, including Maverick and Assassins with Richard Donner (AC Nov. ’94 and Nov. ’95, respectively), and Intersection with old friend Mark Rydell. He has also shot several modestly-budgeted features, such as Sean Penn’s The Crossing Guard and Willard Carroll’s Playing by Heart (AC Dec. ’98). Some of Zsigmond’s best work has passed relatively unnoticed, however. In March of 1989, he filmed a series of interviews with Vietnam War veterans, which served as the heart of a memorable episode of the ABC television series China Beach [Episode 2.12, "Vets"]. His footage provided quintessential proof that the soul lives behind the eyes.

Asked how he selects his projects, Zsigmond replies, “My rule is that if a movie doesn’t say something of value for the audience, I don’t think it’s worth making. You only have time to make so many pictures in your life. Maybe 75 percent of the time, you can tell if a film will be worthwhile when you read the script, but I’ve been fooled on occasion. There were times when I thought something was going to be a good movie, but it didn’t turn out that way. There are so many things that have to come together — the actors, the director, the script.”

“I only have one regret about my career: I’m sorry that we are not making silent movies anymore. That is the purest art form I can imagine.”

But in addition to his many successes, Zsigmond has suffered a few heartbreaks in his career as well, particularly on Heavens Gate (AC Nov. ’80), directed by Michael Cimino, and The Bonfire of the Vanities (AC Nov. ’90), directed by Brian De Palma. Both films were major disappointments at the box office, but serious fans of cinematography would be well-advised to screen these titles for Zsigmond’s fine camerawork.

In 1996, Zsigmond earned an ASC Award nomination for The Ghost and the Darkness (AC Nov. ’96), a film that included multiple digital-composite scenes coupling separate bluescreen elements of a lion with actors in appropriate backgrounds. He considers the evolution of digital technology to be an important extension of the cinematic craft, enabling directors and writers to tell stories that weren’t possible or practical within the limitations of optical compositing.

Zsigmond says that mastering digital post is a skill that every cinematographer must develop, but he cautions that advances in imaging technology shouldn’t be confused with the art of filmmaking. Thinking back to earlier times, Zsigmond points out that he shot McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Scarecrow and Cinderella Liberty with a vintage Mitchell BNC camera. “It took two people to carry it, and it had parallax problems,” he says, “but we still managed to record some pretty good images. I think the most important thing about cinematography is lighting. That’s how you create the mood that matches the story. The ability to light artistically is a gift from the gods. If you have the ability, you shouldn’t waste it. You should be looking for ways to improve and grow.”

Maybe that gypsy fortuneteller who predicted that Zsigmond would sail across an ocean and become a great artist was indeed prescient, or maybe it was just destiny. The reality is that Zsigmond and his lifelong friend Kovacs took their fate into their own hands, and both succeeded because they had the talent and the will to make it happen.

“When I was a student in Hungary, we saw a Western movie with a scene in a Howard Johnson’s restaurant located by a freeway,” Zsigmond recalls. “A teacher said that such places didn’t exist, that the filmmakers must have built a set for the movie. Years later, I was driving on a thruway between New York City and Buffalo, and every 20 miles, there was another Howard Johnson’s restaurant. That’s when I realized how big the lies were.”

During the first decade after Zsigmond left Hungary, the only way he could stay in touch with his former teachers and friends was by writing them letters. In 1969, György Illés came to Los Angeles after a film he had photographed, The Boys of Paul Street, was nominated for a Best Foreign Film Oscar. Zsigmond met him at the airport, and the first words out of Illés' mouth were, “Why aren’t you coming home to visit?” Zsigmond subsequently arranged regular visits to Budapest and the film school. “It was still a pretty closed country until about 1991,” he says. “We couldn’t send the students videocassettes of our movies. The government thought they were propaganda because they showed how people live in the West.”

Zsigmond has since organized an annual two-week seminar at the film school in Budapest. The faculty includes top cinematographers from many countries, and students now come from every part of Europe. “I encourage film students who are interested in cinematography to study sculpture, paintings, music, writing and other arts,” Zsigmond says. “Filmmaking consists of all the arts combined. Students are always asking me for advice, and I tell them that they have to be enthusiastic, because it’s hard work. The only way to enjoy it is to be totally immersed. If you don’t get involved on that level, it could be a very miserable job. I only have one regret about my career: I’m sorry that we are not making silent movies anymore. That is the purest art form I can imagine.”

Before his death in 2016 at the age of 85, the cinematographer was the subject of two essential documentaries, No Subtitles Necessary: Laszlo & Vilmos (2008), directed by James Chressanthis, ASC; and Close Encounters with Vilmos Zsigmond (2016), directed by Pierre Filmon.