Park City Standouts 2019

AC’s observations on an array of outstanding features and docs that screened at the recent Sundance Film Festival, recommended for their creative camerawork.

AC’s observations on an array of outstanding features and docs that screened at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, recommended for their creative camerawork.

The following capsule profiles offer a peek at just a few of the most visually interesting titles to screen at the annual event (January 24 - February 3):

Honey Boy

Cinematographer: Natasha Braier, ASC, ADF

Director: Alma Ha’rel

A raw, emotionally bruising drama about the perils and pitfalls of showbiz parenting, Honey Boy resonated with Sundance audiences, earning a standing ovation at its premiere, forthcoming distribution by Amazon Studios, and a Special Jury Award for Vision and Craft.

The prize was presented to director Alma Ha’rel, but could also be credited in part to her fruitful collaboration with cinematographer Natasha Braier, ASC, ADF, who was determined to work with Ha’rel after watching her stirring 2011 musical docudrama Bombay Beach, which chronicles the lives of three people living in one of Southern California’s poorest communities.

The protagonists in Honey Boy struggle amid equally hardscrabble circumstances. Child actor Otis Lort (played in his teen years by Noah Jupe and as a troubled adult by Lucas Hedges) endures a rough upbringing with his mercurial rodeo-clown father, James (a potent Shia LaBeouf, who also wrote the screenplay based on his own childhood years in Hollywood). Although Otis manages to support the pair financially by landing roles on various productions, the duo reside amid abject poverty in a run-down motel, where James’ battles with his personal problems — alcoholism fueled by his flailing inner rage and the bitter, mocking resentment he aims at his more-successful son — take a tremendous toll on Otis, who eventually lands in rehab and therapy sessions after escaping his father’s orbit.

The intimate nature of the story creates a remarkable level of emotional tension onscreen, as LeBeouf exorcises some very personal demons by channeling his father with an intensely volatile performance. In her cinematographic approach to the drama, Braier tried to remain as unobtrusive as possible, allowing the instinctive LeBeouf to move about freely on set. To give the actor room to roam, Braier set up a system that incorporated LED fixtures and wi-fi transmitters that allowed her to “deejay” the lighting while observing the actors from a monitor. (Her strategy helped Jupe as well, since the young actor wasn’t required to hit marks or be overly precise in his movements.) “I wanted to give Shia a lot of space to improvise, as he would only do a couple of takes — and sometimes just one, with no rehearsal,” Braier noted after the festival. “This approach wouldn’t have been possible a few years ago, before the wide adoption of LEDs and wireless technology. We used Digital Sputnik fixtures, prototypes of Sputnik’s Voyagers, Aspera tubes and ARRI SkyPanels.”

Braier added, “The challenge in this movie was to capture the characters’ relationship and their emotions with the freshness of the documentary style that I loved in Alma’s previous films — and, at the same time, create and a stylized, poetic lighting style and camerawork that would support the story and the characters’ emotions.”

The movie clearly benefits from this strategy, framing its Oedipal conflict in poignantly downtrodden locations that lend its central relationship a melancholic ambience. Braier and Ha’mal use these settings and others effectively, symbolically representing the father-son dysfunction through an accumulation of finely observed details: the motel’s red neon trim hovering over a character’s head; the clutter and decay that surround James and Otis on a daily basis; the child-actor indignities suffered by Otis on set.

As the camera roams restlessly through the story’s environments, flashing back and forth between its two time periods, the father’s inability to transcend his own shortcomings takes on a tragic dimension, demonstrating how James’s overbearing personality and impulse-control problems impact his increasingly distraught son. Nevertheless, the filmmakers’ perceptive and humane approach engenders a surprising amount of empathy for a boorish character who betrays only slim glimpses of parental care and compassion. — Stephen Pizzello

The Last Black Man in San Francisco

Cinematographer: Adam Newport-Berra

Director: Joe Talbot

This is the exactly the kind of indie-bootstraps story that Sundance loves. First-time feature director Joe Talbot got the ball rolling with a $50,000 Kickstarter campaign and ended up with the U.S. Dramatic Directing Award and a special jury prize for Creative Collaboration to boot.

That collaboration was with Jimmie Fails, his best friend since high school. After meeting in a public housing complex in the Mission District, Fails began to act in the short films that Talbot and his brother shot. For this first feature, Talbot and Fails came up with a storyline during the course of long, rambling walks (much like those taken by film’s two leads) that was drawn from Fails’ life — in particular, his love for an old family house in the once predominately black, now gentrified, Fillmore District.

Fails plays the title character, also named Jimmie Fails. As the film’s Jimmie tells it, his grandfather built that Victorian mansion with his own two hands in 1946, and their extended family occupied it until redevelopment and a housing crisis flung them hither and yon — to the city’s outskirts, to SROs, to foster homes. Jimmie returns regularly, nostalgically, to do upkeep, refreshing the paint and tending the garden, despite protests from its elderly white owners. After they move out, he sets his sights on repossessing the home. But with its $4-million price tag and Jimmie’s marginal employment as a geriatric-care attendant, he’s fighting an uphill battle.

Speaking of hills: This film is as much a paean to San Francisco as anything else. Not the touristic side, but the city seen from Jimmie’s skateboard, where marginalized neighborhoods get equal time. Shooting on an ARRI Alexa Mini coupled with ARRI/Zeiss Master Primes, director of photography Adam Newport-Berra often worked with wide lenses at low angles, both dignifying the film’s players and placing them within the city’s embrace. Shot in 1.66:1 to honor San Francisco’s verticality, the film makes use of long traveling shots, slow-motion tableaus, and impressionistic montages to tell its tale with lyricism and leisure, allowing us time to drink up the sights of a city under transition, for better and worse. — Patricia Thomson

Share

Cinematographer: Ava Berkofsky

Director: Pippa Bianco

Another writer-director who knocked it out of the park with her feature debut is Pippa Bianco, winner of the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award for Share. The lead actress, British newcomer Rhianne Barreto, also scored with a special jury prize for Achievement in Acting.

Share tells the story of Mandy (Barreto), a high school basketball player who wakes up one morning in her front yard with no recollection of how she got there or the previous night’s activities. When friends urgently text her disturbing videos circulating on social media, her alarm grows. Though blurry, it seems it’s her being violated by several laughing boys.

The film follows Mandy’s quest to find out what happened. It also traces her increasing isolation as she’s suspended from school for drinking at that party, thus losing connection to teammates and friends. Normal activities are stripped away as she hunkers down in shame in the deepening shadows of her house.

“We talked about that isolation a lot,” Bianco said during a post-screening Q&A, referring to Ava Berkofsky, her cinematographer onan earlier 11-minute version of Share, who reteamed with her for the feature. “Especially when Mandy is in the house, it becomes a prison movie, in a way. She’s in this increasingly small space, and she’s not going out and nobody’s coming in. Those movies were appropriate to the level of pain and hopeless and powerlessness. It was important to have that resonance, and not just be, ‘Oh, she just left school,’ Ava and I thought a lot about ways to have either claustrophobic, very intimate, very sensual shots that were close to Mandy, or spaces that were more objective and voyeuristic, to show her in the context of a confining space.”

Berkofsky shot with an ARRI Alexa Mini, picked for its flexibility and rendering of low light, since much of the movie would happen in shadow or at night, and they wanted to embrace the darkness. She paired it with Hawk V-Lite and vintage Angenieux anamorphic zooms, using their imperfections to create a textured, psychological world. Further enhancing the sense of claustrophobia, the image was framed to a 2.0:1 aspect ratio instead of the usual widescreen 2.39:1.

Acquired by HBO, Share draws from the director’s own experience, the 2012 rape case in Steubenville, Ohio, and interviews with survivors, activists, attorneys, detectives, digital forensic experts, school principals, psychologists, and perpetrators. But all that research gets seamlessly folded into Mandy’s emotionally fraught experience, making this an empathic journey down a very unnerving road. — Patricia Thomson

Native Son

Cinematographer: Matthew Libatique, ASC

Director: Rashid Johnson

Matthew Libatique, ASC returns to his indie roots with this new take on Richard Wright’s 1939 racially charged novel. At the helm was Rashid Johnson, a visual artist and first-time feature director. “My mother introduced me to this book when I was 15,” said the Chicagoan during a Q&A. “She caveated by saying, ‘There are quite a few things about this book and this writer that I like, and quite a few things I don’t like.’ That was the challenge that I kept digging into.”

Johnson recruited Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks (Topdog/Underdog) to pen the script and bring the 80-year-old story into the present. “Richard Wright invented the wheel,” she told the audience. “All we needed to do was roll it forward to 2019.”

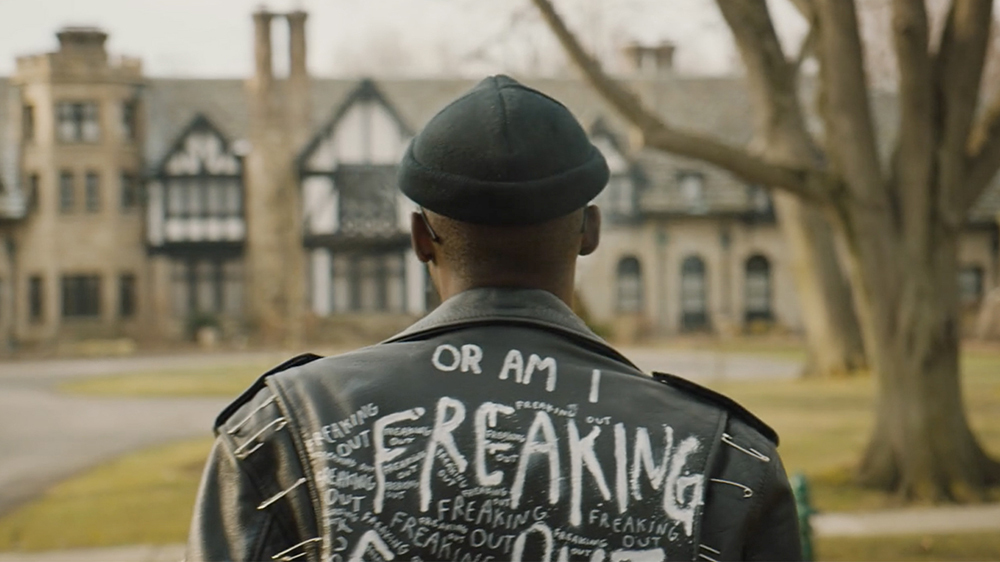

In this retelling, Bigger Thomas (Moonlight’s Ashton Sanders) is a fully rounded person with real potential in life. He’s a North Side black youth who doesn’t fit into any box. With green hair and a graffitied jacket, he’s got a punk aesthetic (nicely signaled with some handlebar-mounted GoPro shots on his messenger bike), but he also listens to Beethoven, indulges in nothing harder than pot, and is reluctant to get involved in a friend’s robbery scheme, despite taunts of being “inauthentic” and a “coon.” When offered good money to chauffeur for an affluent white liberal, he seizes the chance and moves in with the family. Things get complicated when daughter Mary tries to strike up a friendship — both an honest reaching across the racial divide and a superficial badge of wokeness. Then things go off the rails after a molly-stoked evening triggers a fatal chain of events, which a fearful Bigger only makes worse.

Needing a quick pace on a short schedule, Libatique (who also co-produced) once again picked up the ARRI Alexa Mini, the same camera he used on A Star Is Born, for which he received his second Oscar nomination. The Mini was by far the most popular camera among narrative features at this year’s Sundance, due to its versatility. In the case of Native Son, Libatique would often affix it to a Movi Pro 15 combined with a Cinema Devices AntiGravity rig, a body-mounted stabilizer that enables a big lift range, absorbs footsteps, and essentially acts as an affordable remote head.

Inspired by Harlem Renaissance photographer Roy DeCarava and his balance of subject and space, Libatique chose to shoot anamorphic with Todd-AO and Cooke vintage lenses, taking advantage of negative space in the widescreen frame as well as depth from focus fall-off.

Nimbly moving from the lower to upper reaches of Chicago — from rat-infested apartments to sprawling mansions, down-home eateries to lakeside beaches — the film immerses Bigger in modern-day Chicago as it thrust him into a predicament that belies the notion of a post-racial world. — P.T.

American Factory

Cinematographers: Steve Bognar, Aubrey Keith, Jeff Reichert, Julia Reichert, Erick Stoll

Directors: Steve Bognar & Julia Reichert

American Factory, winner of the U.S. Documentary Directing award, shows there’s nothing like verité in the hands of veteran filmmakers. Longtime partners Julia Reichert and Steve Bognar, who have four Oscar nominations between them, offer a fascinating story about globalization and the U.S.–China cultural divide by training their lens on one microcosm: the Fuyao Glass America factory, an automobile-glass manufacturing plant outside Dayton, Ohio, which opened in the husk of a shuttered GM plant.

Six years earlier, Bognar and Reichert had documented the final days of that very plant in their Oscar-nominated HBO documentary The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant. GM forbade them entry, but this time access was unfettered. In fact, Fuyao Glass had reached out to the Dayton-based duo, wanting to commission a film that would memorialize the cornerstone of its intended expansion into the U.S. The filmmakers made a counter-offer: “We told them that to really dive deep, we’d need access to the factory floor, to meetings, to the boardroom ― to everything,” says Bognar. And, of course, they’d need complete editorial control. A believer in transparency, Fuyao’s maverick multibillionaire owner, Cao Dewang, bought in.

With five camera operators divided between key characters, plus 16 others providing additional material, the filmmakers wound up with 1,200 hours of footage captured over three years. Their workhorse cameras were two Canon C100 MK IIs and one Canon C300 MK I. “But we also shot a lot with theSony PXW-X70 on a monopod; it came recommended to us from great docu DP Joan Churchill [ASC], who likes that camera for its compact form in tight situations,” says Bognar.

From that mountain of material, Bognar and Reichert tease out a riveting story, starting with the honeymoon, when 2,000+ unemployed GM workers are grateful just to get a paycheck — though, at $14 an hour, it’s half their former wage. Eventually, a culture clash surfaces. The Chinese criticize American workers’ slow speed, fat fingers, and tendency to chat too much on the job. Americans look at the Chinese and see a robotic lot whose company loyalty goes beyond the pale. When the plant starts bleeding red ink, safety measures lessen, expected work hours increase, and tensions worsen. Unionization rumblings begin, countered by the company’s anti-union blitz (attendance at these propaganda sessions was mandatory).

No commentary is necessary when facial expressions speak volumes. The cameras capture the CEO and his VPs fuming when, without warning, Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown voices support for unionization during the factory’s opening ceremony. When American employees are later sent to headquarters in China to see how things should be done, they’re visibly incredulous at the regimentation, the speed, and the over-the-top displays of company spirit — including a group wedding at a corporate party.

Having no advance agenda, the filmmakers give time to all sides. The fact that the two cultures never mesh, and that increased mechanization leaves factory workers further in the lurch, makes this sobering but necessary viewing. Netflix’s acquisition will make that possible. — P.T.

Midnight Traveler

Cinematographers: Fatima Hussaini, Hassan Fazili, Nargis Fazili, Zahra Fazili

Director: Hassan Fazili

Sometimes one is reminded that content is king, the camera a mere courier. Such is the case with Midnight Traveler. Winner of a special jury award for No Borders, the film’s three Samsung mobile phones sufficed to tell a powerful verité story about the grueling odyssey of a family of asylum seekers.

Hassan Fazili was a successful Afghan director, but trouble followed his Peace in Afghanistan, a nationally televised documentary about a Taliban commander who laid down arms in favor of a peaceful civilian life. (The Taliban subsequently assassinated that commander, then proclaimed the director would die next.)

Thus began the family’s exodus, a three-year journey on the notorious Balkan smuggling route. Early on, Fazili’s wife, Fatima Hussaini — an actress and filmmaker in her own right — sits their two young daughters down and shows them their intended route: Some 3,500 miles across multiple countries to Germany. What she can’t know is the grueling conditions they’ll face: Beds in hallways, safe houses, detention camps, empty construction sites, and frosty fields. Anti-immigrant violence in Bulgaria. A twisted ankle on the run. The sheer boredom of months of detainment in razor-wired “transit zones.”

With few establishing shots, the film stays intimate and cinematic, capturing both these challenges, the landscapes they traverse, and quotidian moments in a loving family’s life: a daughter’s hair blowing in an open car window, the girls’ joy at seeing fresh snow, a marital debate about what’s considered flirting.

With his asylum case pending in Germany, Fazili could not attend the festival, but in a director’s statement he notes, “Working with the mobile phones, we discovered a style of framing and camera movement that captures the experience of our family on the run. At the same time, we are working to intertwine our reflections on the journey in order to expand the interiority of the characters.” As the daughters grew, they joined their parents in capturing these moments, which ultimately amounted to 300 hours, plus 25 hours of voiceover. Unable to travel with his laptop, Fazili worked with producer/writer/editor Emelie Mahdavian to smuggle his SD cards to safety. He’d wipe the cards clean, then start anew, keeping production lightweight and mobile.

There’s no tidy ending to Fazili’s story; that may be years away. But the scenes captured in Midnight Traveler remain indelible. Viewers will never look at asylum seekers or refugee caravans in quite the same way. — P.T.

Judy & Punch

Cinematographer: Stefan Duscio, ACS

Director: Mirrah Foulkes

Those well versed in the particulars of Punch & Judy puppet shows will recognize Judy & Punch as a live-action reimagining of the ages-old slapstick amusement. Directed by Mirrah Foulkes and shot by Stefan Duscio, ACS, the Australian feature follows a 16th-century husband-and-wife team who run a traveling marionette show. The charismatic Punch (Damon Herriman) offers himself as the face and talent of the operation, though it’s quickly clear that Judy (Mia Wasikowska) is really holding things together. Indeed, Punch’s drinking has led to the near collapse of their theatrical endeavor, and ultimately to the very actions associated with his absurd puppet counterpart — which when translated to a live-action scenario veer from the comical into the truly heinous.

Alternating between locked-off camera and steady movement — and eschewing handheld — Duscio and his team adeptly frame an outlandish allegorical tale that unfolds in Seaside, a town steeped in a frenzied fear of witches and rife with citizens’ eagerness to blame anyone for their troubles but themselves. The story opens with a cloaked figure running through the rural village at night in a long, smooth single shot. Another oner then takes us inside a theater, where we witness a raucous, bawdy crowd gathered to see the spectacle.

Punch introduces his show to fawning applause, before disappearing in a puff of smoke. In the rafters we see Judy working the strings of a marionette, her face side-lit in the dimly illuminated space. She operates alongside Punch as they create the slaphappy antics below. After the curtain falls, we find the couple backstage in a darkened candlelit sequence as Judy fruitlessly petitions Punch to pull back on the show’s increasingly “punchy and smashy” bent.

When Judy is severely maimed — following a frenetic sequence featuring Punch tearing through their estate in pursuit of a dog who stole his breakfast — a group of children spirit her into the forest, and we learn that many accused of sorcery have escaped to this utopian wooded refuge. Her visage bathed in the orange-tinged light of the workroom of Dr. Goodtime (Gillian Jones), Judy is brought back from near demise to seek vengeance upon Punch and justice for her rescuers.

Among Duscio’s day-exterior wide shots, perhaps the most impressively framed is one featuring a motley crew of dissidents practicing tai chi in the woods (to the tune of Leonard Cohen’s “Who by Fire”). Having premiered in the Sundance Film Festival’s World Cinema Dramatic Competition, Judy & Punch takes a remarkably simple visual concept — a handful of hand puppets — and expands it into a wild widescreen exhibition rich in both imagery and ideas. — Andrew Fish

Clemency

Cinematographer: Eric Branco

Director: Chinonye Chukwu

When an execution she is overseeing runs into harrowing complications, a veteran prison warden’s long-garrisoned faith in the system begins to collapse in Clemency, directed by Chinonye Chukwu and shot by Eric Branco. Having prided herself on following policy to the letter while honoring the humanity of the inmates under her charge, Warden Bernadine Williams (Alfre Woodard) is now left with an unfamiliar sense of uncertainty — especially in the face of the next execution on the docket. The case of Anthony Woods (Aldis Hodge), who stands convicted of killing a police officer, is riddled with enough inconsistencies to bring big questions to the public conversation, and teems of protesters to the prison.

Clemency’s understated cinematography is punctuated with visual choices that keep viewers on their guard. For the execution scene that launches Williams into crisis, Branco’s toplight creates contouring highlights on her face, while simultaneously fully illuminating the doomed inmate (Alex Castillo) who lies on a gurney. The scene is followed shortly after by a striking overhead shot of the warden walking through a prison hall. And the dimly lit ambience that, for example, permeates Williams’ strained home life with husband Jonathan (Wendell Pierce) sharply contrasts with the bright, light-drenched whites of the inmates’ uniforms.

The feature’s smooth and steady camera movement is disrupted on selected occasions, such as when Williams and her husband have their candlelit anniversary dinner. The sequence begins with a restrained handheld style — a look that foreshadows the pronounced unsteadiness that overtakes the sequence as percolating resentments boil over.

The production — which won the U.S. Dramatic Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, where the movie premiered — is also peppered with a number of shots that appear to complement each other. The most notable of these is a slow pull-out to a melancholic wide angle as Williams seeks emotional refuge at the local bar, which cuts to a push-in on the prison’s starkly sunlit frosted window panels.

A boldness of technique is also evidenced when Williams reaches her wit’s end. For this pivotal moment, Branco ensured that the camera was close on her — and remained for a long while before the warden’s march into the light of day. — A.F.

Light From Light

Cinematographer: Greta Zozula

Director: Paul Harrill

Light From Light follows a part-time paranormal investigator as she seeks a definitive answer for a widower who can’t shake the feeling that his wife is reaching out from beyond. Shelia (Marin Ireland), a single mom who makes ends meet working at a car-rental company, is sought out by a member of the clergy (David Cale), who asks if she would look into the concerns of a congregant named Richard (Jim Gaffigan). Enlisting the help of her son, Owen (Josh Wiggins), and his special friend, Lucy (Atheena Frizzell), Shelia delves deep into the house that Richard once shared with his wife and deeper still into Richard’s feelings about his love and loss.

Most immediately apparent about Greta Zozula’s cinematography is an attention to detail in darkened spaces. As Shelia explores the interior of the house at night, her flashlight flares — and later projects its light onto a wall, bringing our protagonist into silhouette. Accenting the overall design are specular highlights dappled on such surfaces as the varnished wood of the bannister. When Shelia turns on a light in the bedroom, the effect still accentuates the dark, illuminating her face in a way that’s more haunting than revealing.

Looking to help Richard find closure, Shelia takes him on a hike to the site where his wife’s plane crashed. After some adept moving-car-interior shots on a wooded road, Zozula and her crew embarked upon exterior work on a cloudy day in the forest. A particularly well-framed shot features a tiny sprouting plant in the foreground and the wreckage behind it.

Though darkness and overcast skies feature prominently, it’s the cinematographer’s work with day-interior illumination that serves the feature’s denouement. Early in the movie — which premiered at Sundance in the festival’s Next category — we’re given a quick look at Richard’s front door, which is outlined by windows through which light pours in and blows out the frame. The image is fleeting yet memorable, and when we see it later under more portentous circumstances, it’s both familiar and imbued with newfound spirit. — A.F.

You'll find the official Sundance Film Festival award-winners release here.

You'll find more about AC's Sundance activity here, featuring livestreamed filmmaker discussions from the Canon Creative Studio.