Mastering the Airwaves: Peter Levy

Our 2022 Career Achievement in Television Award honoree surveys his journey into episodic excellence.

It was the late ’60s, the height of the counterculture, and like many youths of the time, 17-year-old Peter Levy refused to follow the conventional route for middle-class Australian kids like him. The future ASC and ACS member dropped out of high school. That same day, he found a job — helping a photographer relocate from the suburbs to a Sydney warehouse — that would unknowingly set him on a career path and alter the trajectory of his life. A little more than five decades later, Levy has been honored with the 2022 ASC Career Achievement in Television Award — a milestone whose origins he can trace back to that job.

While whitewashing the walls of that warehouse in Sydney, Levy watched the photographer’s process and thought that he might be able to do this kind of work, too. So, Levy shot a few rolls of film and processed them at a local university, where the resident photographer gave him the highest praise any new shutterbug could receive: He had a good eye. Levy and a friend soon set up a photography studio in the latter’s garage — a business venture — but it wasn’t until his sister Sandra hired him to shoot stills on a short film she was helping produce, The Machine Gun, that Levy discovered where his budding interest in photography could take him. On that set, he got his first real glimpse of what a cinematographer did.

“Since that day, there was never a doubt in my mind that cinematography was what I was going to do,” Levy tells AC during a meeting with him at his home in Los Angeles.

The Emmy-winning, ASC Award-nominated cinematographer learned from the best. After starting his career as an assistant for freelance cinematographers, Levy was hired by Australia’s Commonwealth Film Unit — “which met all the filming requirements of 27 different government departments, narrative and documentary,” Levy says — where Peter Weir, Phillip Noyce and Gillian Armstrong were staff directors, Chris Noonan (future director of Babe) was a PA, and Dean Semler, Don McAlpine and Michael Edols — the latter of whom became Levy’s mentor — were staff cinematographers. (Semler and McAlpine were later invited into ASC membership, and all three achieved membership in the ACS.)

“The very first frame of film I shot in my own right was for Peter Weir,” Levy recalls of his time at the Film Unit. The chief cameraperson then told him that Weir “needed a pickup shot for one of his movies of someone getting off the train at Central Station, and I was dispatched to do it,” Levy says.

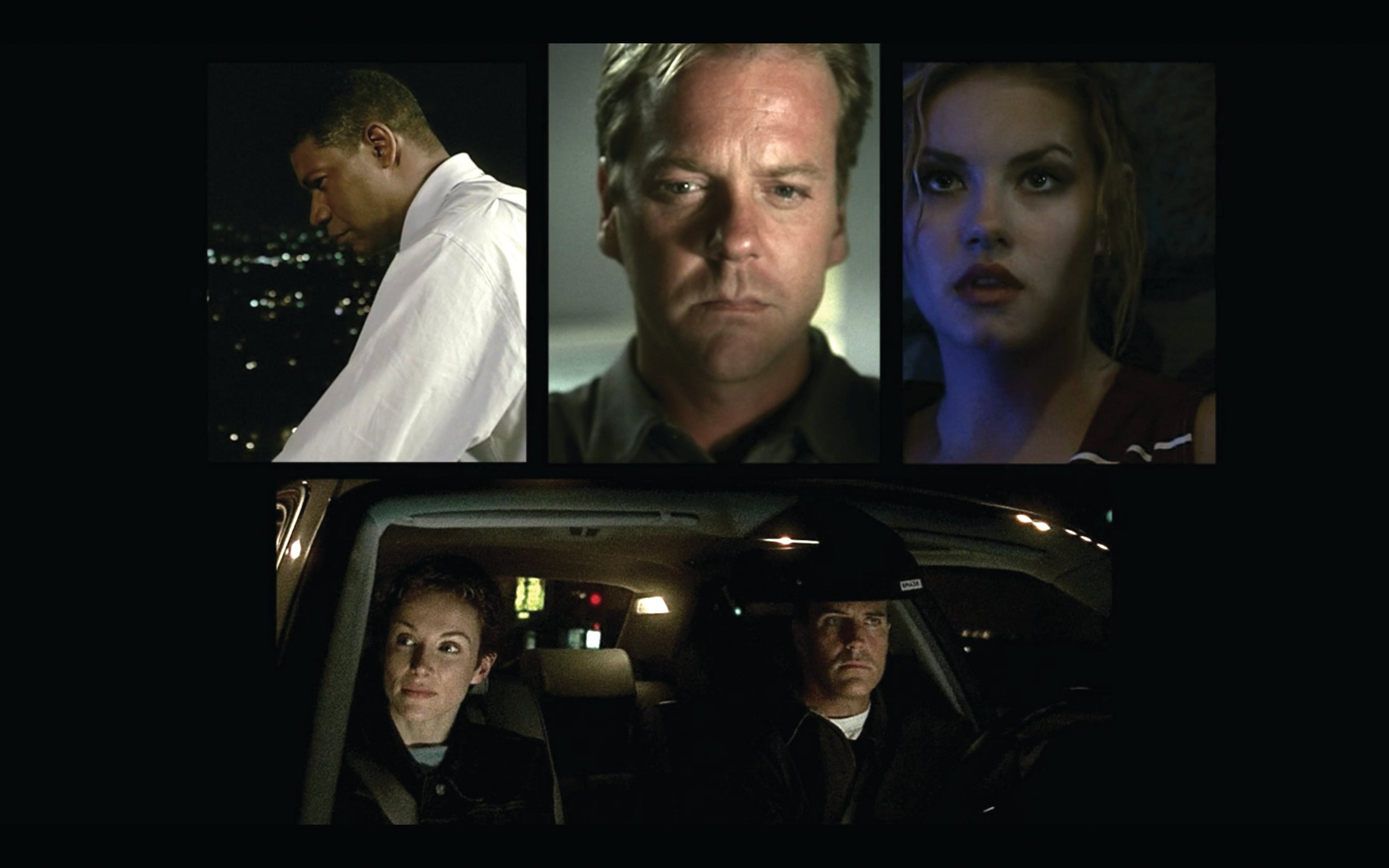

longtime collaborator Stephen Hopkins.

The Film Unit in the early ’70s proved to be an incredible training ground for Levy. One month, he would be sent to sea with the Royal Australian Navy to shoot missile tests off the deck of a destroyer, and the next month he would be sent to New Guinea for a piece about a cable that provided telecommunications services to the remote Highlands for the first time. After that, he would travel throughout the Australian Outback to film a short about Aboriginal Australians’ housing.

“Looking through the eyepiece, shooting film, became a very familiar place for me. That’s what documentaries gave me,” Levy says. “The eyepiece was like my office. Just having a camera on my shoulder, rolling, was a very familiar place for me. I was confident with a camera.”

This self-assurance and experience became vital when his team was ambushed while on a shoot in Cambodia. “The driver was badly shot. I was grazed by a bullet. The Khmer Rouge were trying to assassinate us because we had a well-known journalist with us. It was a pretty terrifying situation,” Levy says. “But just having that camera, I was thinking about exposure, focus, how much footage was in the mag, that if I shot this now, I would have to do a reverse shot as well. I managed to put myself back together in a panic situation because I could do it through my camera.

“But that was amongst the last times I did documentary work. I realized I wasn’t prepared to die for this. I’ll live for it, but I won’t die for it.”

Levy soon moved into more commercial fare. His first major job in scripted filmmaking came in 1983 when French director Henri Safran saw Levy’s past work and hired him to be his cinematographer on the television miniseries A Fortunate Life, based on an Australian bestselling novel. During the eight-month shoot, Levy discovered his camera skills allowed him to quickly grasp techniques for which he had no prior training, such as “capturing special-effects shots with painted-glass mattes and hanging miniatures” that were necessary to re-create the landing at Gallipoli. “It was easy enough to get troops to run up the beach, but behind them, we needed the British fleet,” he says. “To do that, we got a whole lot of model warships and stuck them on glass so that when seen through the camera, it looked like they were sitting on the horizon. It’s such a great delight making magic in the camera. In the film days, we were trained that what came out of the camera was what the public saw. There was no digital manipulation or anything that could be done because it was just your photography that went out there.”

At the time, Levy also shot hundreds of music videos, which gave him the opportunity to experiment with new technology and “get rid of all of my stupid lighting ideas, by trying all sorts of different lighting fixtures and combinations. I used colored gels with abandon. Sometimes what sounds good doesn’t always look good.” It was on one such music video in 1984 that his career and life changed again — in a major way. “I don’t remember the band,” Levy says of the video, “but I remember the light.

The video’s director, a young British-Jamaican man named Stephen Hopkins, asked for shadows from Venetian blinds to come across the floor. Levy suggested putting an HMI outside the window, but Hopkins had another idea — impressing Levy with his visual acumen. “I’ll never forget this,” Levy recalls. “He said, ‘I’d rather use a brute [carbon] arc for its crisper shadow.’ And, I thought, ‘Wow, awesome. I love this director.’”

The two formed a close friendship and a dynamic collaborative partnership. They teamed on the director’s first feature, the Australian slasher Dangerous Game (1988), and afterward, New Line Cinema in Hollywood offered Hopkins the job to direct A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child. Hopkins insisted Levy be brought over from Australia to serve as cinematographer, and Levy has remained in Los Angeles ever since.

Levy has continued to shoot most of Hopkins’ projects, including such big-budget blockbusters as Predator 2 (AC Jan. 1991), Blown Away (1994), and Lost in Space (AC April, ’98), and smaller dramas including Race (AC, March ’16) — as well as television projects such as the TV movie The Life and Death of Peter Sellers (AC Dec. ’04) and the series 24, House of Lies, and most recently Liaison. Levy has had successful collaborations with other talented directors, such as John Woo, Renny Harlin and Todd Robinson, yet the cinematographer feels that his relationship with Hopkins is one-of-a-kind. “I owe my career to Stephen. Everything in my career that’s worthwhile has got Stephen’s fingerprints all over it,” he says. “I’m forever mindful that he’s the director — that it’s his vision I’m there to support. I’ll offer up any ideas and suggestions, but I’m happy for him to refine them any way he wants. He also knows how I photograph things. When he sees the scene in his head, my guess is that he sees my photography.”

Filming 24

Levy and Hopkins’ collaboration on the pilot of the Fox action drama 24 disrupted the norms of network television through the iconic look they created. In order to best visualize the series’ real-time method of narration — in which every episode was exactly an hour of storytime — the filmmakers decided against the traditions of three-point lighting, master shots and reverse close-ups. Instead, Levy and Hopkins opted for a more realistic approach to convey the tension of the show. “The concept of 24 is that you can only cut to change location — you can’t cut to change time. So, you couldn’t use the edit to compress time. It had to be real-time, and the cut had to be a match cut,” says Levy, whose camerawork on the pilot earned him his first ASC Award nomination. “Stephen was lamenting the fact that he didn’t have enough time to get all the coverage he wanted for all the cuts he knew were necessary. I said, ‘Let’s shoot this documentary-style and then consider whether we need to do any additional shots to make that scene work, or whether we can choreograph it with two cameras.’”

But they didn’t deploy the two cameras to secure coverage, per the common practice. “We might start a scene with one camera in one room, and when the actor walks out of that room, the second camera was outside the room, and we’d pick the actor up from there, and shoot the second half of the scene,” Levy says. “Rather than shooting with two cameras to get different angles on one shot, we would use them to extend the set and the shot.”

Krishna Rao, who served as Levy’s camera operator for many years until he became a cinematographer and director in his own right, operated the camera on the 24 pilot and remembers the intensity of that shoot. “I was challenged with a tricky shot — director Stephen Hopkins doesn’t do easy shots. I asked Peter for another rehearsal, and he denied my request, saying he didn’t want the audience to get the impression that I had a chance to rehearse the shot. He said he wanted viewers to feel that we barely had time to set up the cameras before the action happened,” Rao says. “There is an immediacy to the action if the camera feels unrehearsed and reactive to the action in frame. Sometimes it’s okay, even beneficial, if an actor’s head breaks frame on a standup or if you miss the first word of dialogue when panning over to see who’s talking. This reactive style is something I carried over to when I started shooting the [CBS action drama] The Unit. You make it real by making it less than perfect. Not sloppy — real.”

To craft the television biopic The Life and Death of Peter Sellers (AC Dec. ’04) — which earned Levy another ASC Award nomination — the cinematographer and Hopkins allowed Sellers’ pained mindset to guide the production’s lighting. “Sellers hated his life,” Levy told AC in 2004. “He only thought he existed and had value when he was onscreen, so that affected our lighting and shooting. The scenes when he’s making films are hyperreal, deliberately theatrical, whereas scenes depicting his normal life are not glamorous at all. I tried to be more miserly with light for scenes showing him offscreen, and excessive with it when he is working.”

For the Showtime comedy House of Lies, “The overriding idea was that we were making a comedy about management consultants,” says Levy, whose work on the show garnered him two more ASC Award nods. “Their world is slick. It’s clean — not grainy or shadowy. I wanted to give it a certain level of gloss.” He and Hopkins shot the bulk of the series’ episodes, and always strove to move away from the conventions of television comedies. “It used to be a truism in comedy that the camera was really just a recording medium and it couldn’t contribute to the creative process. We didn’t accept that on House of Lies. It’s quite clearly a comedy, but we tried to shoot it as dramatically as possible, and often broke the fourth wall and crossed the line whenever we could.”

The upcoming Apple TV Plus thriller series Liaison required Levy and Hopkins to work within tight boundaries, which appealed to the cinematographer. “I get pleasure from adapting, modifying and improvising,” he says. “We found this place to shoot — an old telephone exchange — that had no windows. It’s supposed to be a hackers’ hideout in Syria where some quite complex action takes place. We built a false wall in there that contained two false windows to the ‘outside,’ which we covered with random wooden slats — through which I shined two open-face 5Ks with my favorite dirty-yellow [Lee 104 Dark Amber] gel to simulate sodium-vapor streetlights from below, which threw shadows on the ceiling. The building had skylights, so I got my grips and electrics to blackout all of them except one — and for that one I put up some greenish gels and an ND to give a lovely, soft top ambience — relying on natural light. It lit this huge area quite dramatically and gave the director full 360-degree flexibility, with no lights on set. I was delighted with that, because the light from the skylight was free, and with gels and NDs, I could control it.”

Fifty-plus years after deciding to become a cinematographer, Levy — whose additional accolades include two Emmy wins, for Californication and Sellers — is a true master of his craft. But his skills extend well beyond the camera and lights to his interactions with the people around him. “Working with Peter is like working with a family member or one of your best friends,” says Alan Cohen, Levy’s longtime 1st AC. “You can talk to him about anything, which makes for easy communicating to ensure we are always getting the best possible results in every scene. He appreciates every individual’s hard work, and he compliments you when you pull off a really difficult shot.”

Michael Joseph Reyes, who worked with Levy for more than 15 years as key grip, admires how he prepares and treats his team. “Peter would walk with a viewfinder during a first-team rehearsal, and throw hand signals to us with lens sizes and dolly marks for the A and B cameras, so that we knew all the camera angles and lighting direction,” Reyes says. “When the AD asked if he was ready to shoot, Peter would ask us, ‘Are you ready?’ We’d say ‘Yes, Peter.’ And he’d reply to the AD, ‘If they’re ready, then I’m ready.’ It doesn’t sound like much, but it was huge for me to have his respect, collaboration and protection on set.”

Levy was invited into Society membership in December 1999, with recommendations from ASC members John A. Alonzo, Russell Carpenter and Peter James.

On being honored with the ASC Career Achievement in Television Award, Levy says, “I’ve always tried to do good work, and interesting work. I’ve always tried to avoid the cliché. But there are times when you wonder whether anyone else notices. So, to have my peers acknowledge my work is…” His voice trails off in a moment of strong emotion. Once composed, he continues:

“I’m a member of the only club I’ve ever wanted to be a member of. And for them to recognize my work means the world to me.”