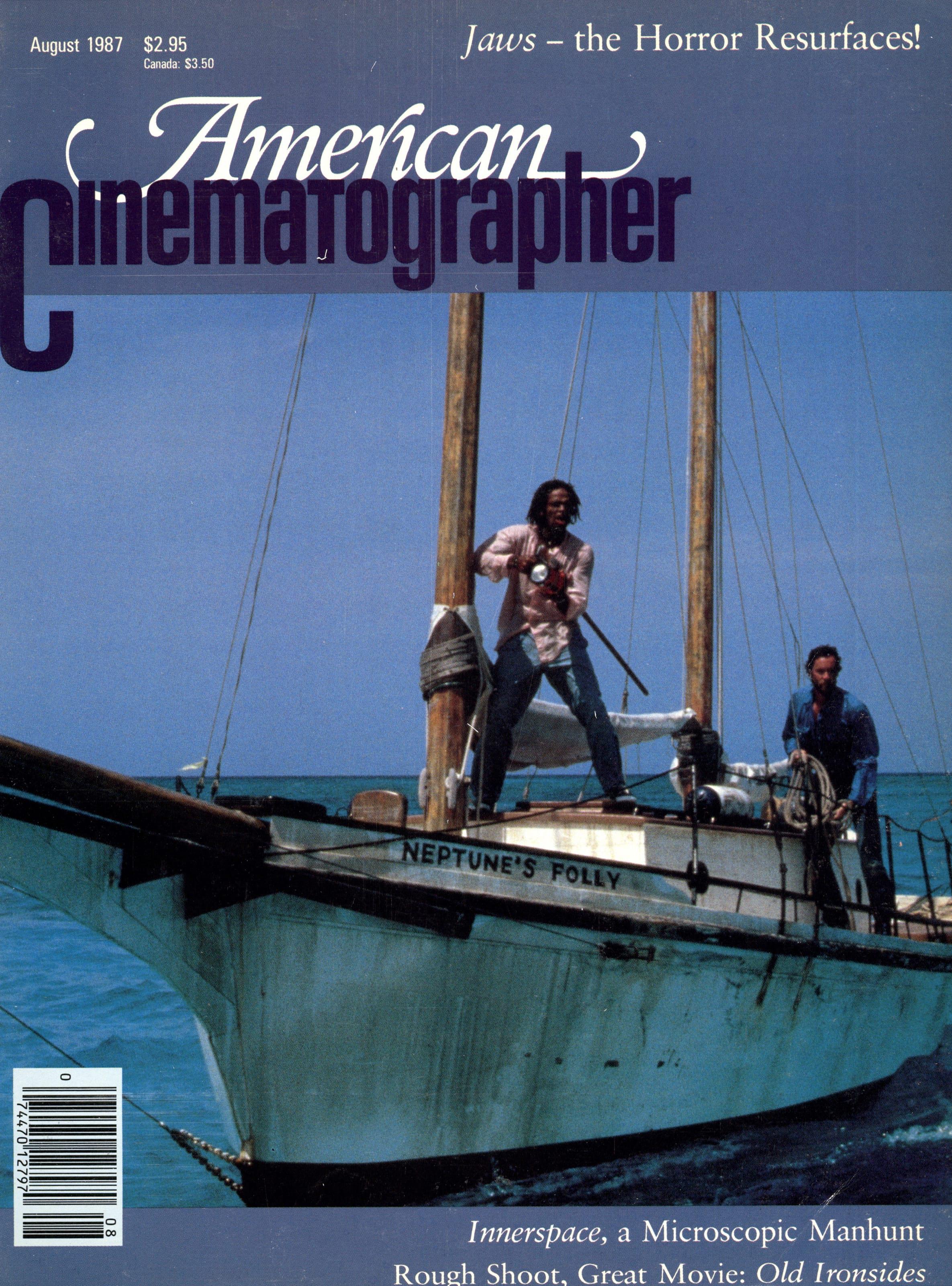

Predator Dispenses Invisible Terror

Director of photography Don McAlpine discusses his work on the sci-fi action feature, involving remote locations and complex effects.

Unit photography by Zade Rosenthal

The latest summer hybrid, Predator, from 20th Century Fox, combines elements of two similar top-grossing films: Commando and Alien. Formerly entitled Hunter, the Jim and John Thomas screenplay features a creature that is the ultimate predator. Like a terrestrial chameleon, it has the ability to mimic whatever background environment it inhabits so perfectly that it becomes completely invisible when motionless. When moving, a faint rippling Fresnel-like outline betrays its presence.

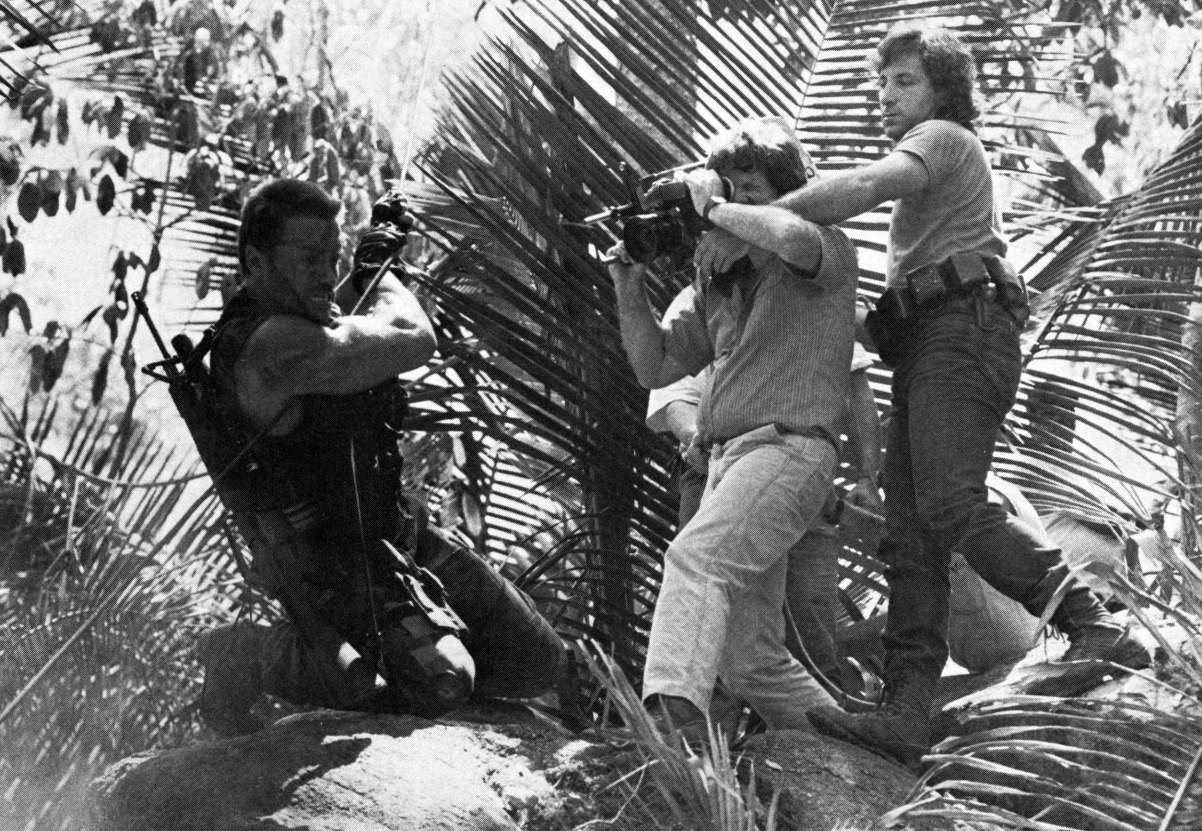

The creature is a hunter. It enjoys a challenge. The Predator travels from world to world searching for the most dangerous being to stalk and destroy. On Earth, the game happens to be Major Alan “Dutch” Schaefer, played by Arnold Schwarzenegger. The Predator comes to our world just as Dutch and his crack military rescue unit are looking for allies captured by guerrillas in the dense Latin American jungle. It proceeds to hunt the highly trained men, eliminating them one by one until Predator and Dutch are the only ones left.

The director of photography for this highly visual film was Don McAlpine. Before this, the Australian cinematographer worked in his native country as lead cameraman on a slew of government-produced films that coincided with the blossoming of Australia’s film industry. He worked with director Bruce Beresford on one of the first films to introduce the new wave of that country’s feature filmmaking, The Getting of Wisdom. He later advanced from shooting a feature every two years to four films per year, which included such award-winners as Breaker Morant for Beresford and My Brilliant Career for director Gillian Armstrong.

Eventually, McAlpine began filming American productions overseas in Manila. The good fortune of working on some of the most successful Australian films to be released in the United States led to his being hired by director Paul Mazursky in 1981. Since then, he has worked on several of Mazursky’s films — among them, Tempest, Moscow On the Hudson and Down and Out In Beverly Hills.

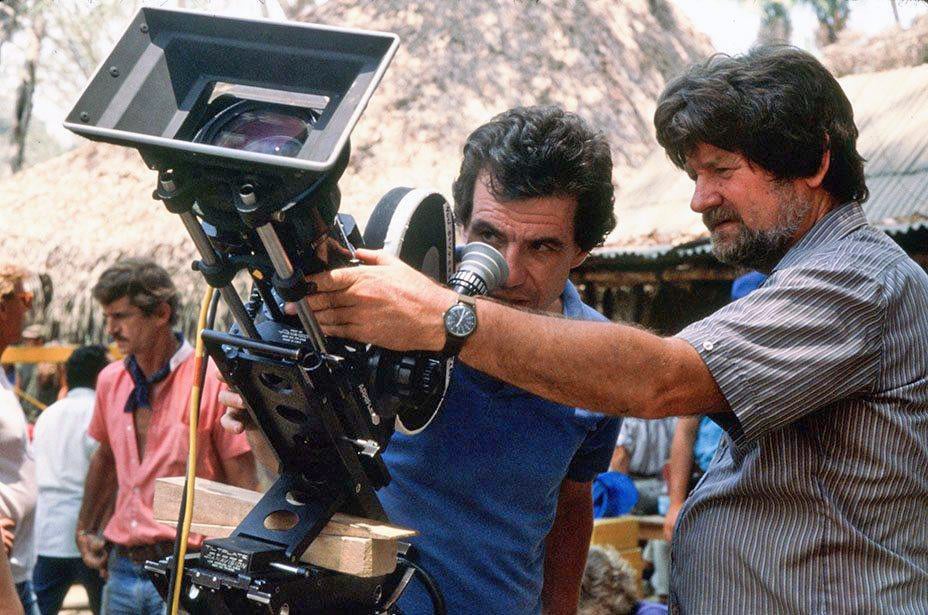

The director of Predator, John McTiernan, asked McAlpine to become involved after seeing some of his previous films. Unfortunately, he was granted only two weeks of pre-production, a very short term for a project of this complexity. Initial thoughts for locations involved shooting in Mexico and using crews from south of the border. But when they arrived, the lack of ability to communicate in detail, needed for the many intricate special effects sequences, became a definite problem. So, McAlpine had to use additional crew from Australia to complement his team.

“At that time, I was in a bit of a hiatus with the union [Local 600] because I was a group 2,” McAlpine recalled. “I couldn’t do feature films in Los Angeles, but I could in New York. As [Predator] was outside their jurisdiction, I was allowed to work on it.” McAlpine was only involved with principal photography in Mexico for the jungle exteriors. Any shooting needed in the States was to be handled by 2nd-unit special effects teams based in America. As it turned out, in the middle of shooting, all Local 600 groupings were abolished and now McAlpine can work in L.A. without any trouble.

Predator’s principal photography can be divided into two periods: the time in which Richard Edlund, ASC’s Boss Film special effects company was involved, back in Spring of 1986, and the February ’87 shoot, when Stan Winston’s company took over make-up and creature effects. Most of the principal photography had been completed with cast members during the first six-week shoot. The second period primarily involved the final climactic battle sequence, when Dutch, the sole survivor, goes one-on-one with the Predator. Fortunately, the creature is not really seen in full body until the film’s end, so only some of the previous footage that accompanied make-up effects had to be re-shot in the remaining five-week period.

McAlpine hinted that limiting time factors were partly responsible for the unusable footage obtained during the first shoot. “Most of the special effects work was supposedly designed and blocked before we started,” he said. “I think the whole thing was probably started a little soon.

“But, inevitably, with commercial considerations, this happens on all but the most exceptional movies. The lesson for me is never go into a special effects movie unless they really have enough time to resolve a lot of the problems.” He wonders if that will ever be the case. The original creature suit, worn by martial-arts actor Jean-Claude Van Damme, was intended to be partially covered by 3M Scotchlite material. Onto this was front-projected various patterns to reflect the creature’s current mood to give it more density than just a flat costume. Filmed separately, the projected elements consisted of white TV snow for anger, static electricity for confusion and rushing water for its few moments of calm.

According to McAlpine, these were photographed outside, some with long 300mm lenses. “We shot either Friday or Saturday morning, the studio saw the results on Monday, and I was back in L.A. on Tuesday evening. That’s when they re-grouped and decided first, whether they had a movie, and second, what they needed to complete it.”

Evidently, the discussions came out positive. McAlpine was called back to the production in early 1987 as the rest of the crew regrouped in Palenque, an historic archeological site in southern Mexico near Guatemala. He had just finished shooting another project during the eight-month interim, Orphans, and believed the long delay was due more to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s commitments on the film The Running Man, than the time it took to regroup. “The new location turned out to be much nearer the dream we had, and it was the place that we had declined in the first location survey because of the logistics involved in servicing it,” McAlpine added. But, not everyone was brought back. By then, they had already filmically “killed” much of the cast. They had progressed with the script to where it was basically just Arnold and the creature — the showdown sequence — the most difficult part of the picture. Concerning material shot in the early stages, there were some additional pickup shots to expand and develop. But most of it (nearly three-quarters of the film) stayed as it was.

Panavision equipment was obtained from Mexico City along with Panavision Z series lenses. The slower T1.9 glass was used on the first half and Superspeed Zeiss optics on the second. Most of the filming for both shoots was accomplished with primes. Zooms were employed only when needed, which was not very often. “I had less flaring problems with the faster Zeiss lenses than with the slower,” said McAlpine. “They seem a better all around lens and I’m using them for the production I’m on now.” He is currently working on Moving, starring Richard Pryor.

All principal Predator photography was shot either with 35mm 5294 or 5247, depending on lighting conditions. “Artificial lighting in the jungle, particularly on an action movie, is almost impossible,” explained McAlpine. “Your biggest problem is the dense undergrowth. It’s all top light. You read it with a meter one way and it reads 60 (footcandles). Hold it another and it reads three. There’s nothing coming off the ground, as you’d expect.

“Once you introduce a light, all it does is light the foreground to an excessive degree so that it looks obvious. Occasionally, I used very broad distant sources where I could get them in. I needed the speed of 5294. Oftentimes we were still shooting at T2 in anything but the middle of the day.”

He switched to 5247 when set-ups involved wide clearings. One of these shots dealt with a bear trap covered with leaves that the men rig to try to capture the monster. HMI lights created fill for cutaway shots of the men. When the trap springs into the air, followed by a shower of leaves, no fill was needed as the camera aimed at the sky.

“There’s no problem matching [the two stocks] as long as you don’t cut them together in the same scene,” McAlpine points out. “When you come to a bright sunny shot, everyone seems prepared to accept the fact they see more detail, but when you climb into a jungle it gets a bit murky in the grays.”

McAlpine rated the 5294 for its standard exposure index and has strong feelings as to the rating of films in general: “Film is what it is and it’s processed to very fine tolerances in all labs around the world. You might find a third of a stop difference. I go for a pretty heavy negative. I carry a densitometer and do my own tests. If the printer numbers average about 30 to 36, I’m very happy.”

Some cinematographers force the lab to print film their way by slightly over or underexposing the negative. In effect, they change the film rating to suit their style. “Film has an El or ASA and what you do with it is your business. In their mind they’ve changed the ASA. But all they’ve done is underexposed or overexposed. They’ve changed nothing. In the interests of precision it’s better to talk about what you’ve done as opposed to what you’ve imagined you’ve done,” McAlpine concluded. Being in such a remote location as Palenque, film processing was not your typical overnight affair. A long four-day turnaround existed, mostly due to U.S. and Mexican customs relations. McAlpine received reports from the lab usually two days after. If printing lights were in the 30s, he knew he was okay.

During the initial shoot, dailies were often sent to the location on video. “I objected most strongly to this, virtually to the point where I refused to look at them,” McAlpine admitted. “There’s no point in it to me. It’s bad enough you’ve got to look at a work print from the lab. Then to take that print and transfer it onto video with no concept of what controls they had... to virtually change it to a whole other medium and make judgments on that...the lab numbers are good enough. You can’t judge focus, color and lost detail on video.” Video dailies seem more of a director’s tool at this stage. The production eventually ordered a portable double-system 35mm projector.

The crew averaged 15 setups a day when not filming special effects. According to McAlpine, director McTiernan rarely went for straightforward shots. Nearly every shot had a visual or action edge that necessitated a complex camera movement. “The Nettmann Cam-Remote [by Matthews] was utilized as much as I’ve ever used it in a movie,” he acknowledged. “We averaged five set-ups a week on it; sometimes three per day.” The crane is cheaper to have on hand than a Louma. A normal-size crew can assemble it without bother, as it breaks down into small pieces for shipping. One of its prime advantages is that the camera lens height ranges from six inches off the ground to 23 feet high, making it a very versatile piece of hardware. The Cam-Remote was employed on several jungle tracking shots. Also on hand throughout was a Steadicam, operated by first assistant Rob Agganis from Australia. The system was adapted to hold a film-and video camera arrangement tied together on the same configuration via beam splitter for running point-of-view shots of the creature.

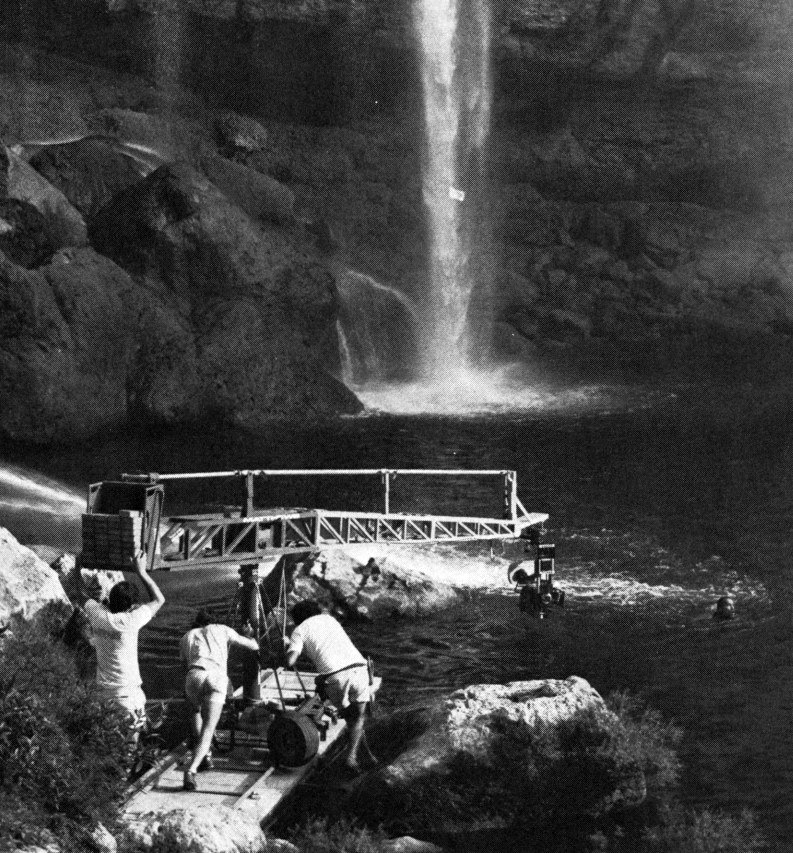

The climactic battle between Dutch and the Predator proved to be the most difficult part of the shoot. It took place entirely within a ravine virtually 1,000 miles from nowhere — two days drive from Mexico City — and mostly at night. The area was so expansive that Australian gaffer Warren Mearns rigged a bank of Dino lights which consisted of 2K spot lamps, each at 3200 Kelvin. He placed them atop a waterfall at the head of the ravine. These provided McAlpine’s sole key illumination.

“I was getting 7 or 8 footcandles down there,” he remembered. “After they started using a lot of smoke, I’d end up with 4 or 5 footcandles for a key light. We never forced [the film]. Our stop was a T2 — most Zeiss lenses sustain a good image around 2. The ravine at night is a dark scene to begin with. You’re not exposing it for daylight, so it’s not going to carry the same density.”

McAlpine kept the lights about 30 to 50 feet away from the subject. This avoided the hot foreground look discussed earlier and made fall-off less perceptible. “With rocks and jungle at night you can’t introduce light anywhere near the camera or else that rock is going to be three stops too bright,” he warned.

Before a campfire, Dutch dons war paint and prepares for the fight of his life. The crew rigged up a propane gas mechanism so they could control the firelight. Here it didn’t matter that Schwarzenegger was well-lit since he was so close to the flames. The scene was photographed at T1.6 during magic hour as it was used for a transition between day and night.

“At one point in the beginning, I had to walk away from a strict reality to the point where it became fantasy,” said McAlpine. “In all films in which I’m trying to portray a reality, I always try to justify every light source. Otherwise, the audience, even without any technical knowledge of lighting, senses an air of unreality.”

A longtime member of the Australian Society of Cinematographers, McAlpine later became a member of the ASC and went on to shoot a series of popular movies in the 1990s spanning multiple genres, including Patriot Games, Mrs. Doubtfire, and Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet.

In 2002, he received an Academy, ASC and BAFTA nominations for Best Cinematography with the spectacular musical Moulin Rouge!

In 2009, McAlpine was honored with the ASC International Award for his outstanding body of work.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.