Photographing Fitzcarraldo

Cinematographer Thomas Mauch relives the difficult journey of filming Werner Herzog’s iconic drama on location in Peru.

This article originally appeared in AC August 1983. Some images are additional or alternate.

By Thomas Mauch

Black-and-white unit photography by Beat Presser

Fitzcarraldo is the latest film by German director Werner Herzog. It was a project that he labored on for over three years, with an actual shooting schedule in excess of eight months in both South America and Munich. I spent most of those eight months on location in South America, and we worked seven days a week for virtually the whole time. The only breaks we had were when some major piece of equipment broke down, and due to our very remote location we had to be fairly self-sufficient as far as food, health care, and technical backup were concerned. Fortunately we were down only three or four weeks out of the whole schedule. In my role as director of photography, I often acted as operator, focus-puller, assistant, loader, repairman, doctor and patient, and baggage handler at one time or another during the production. That’s how Herzog makes films, good films.

“It has been said that Herzog was placing his crew and people in constant danger. This is an exaggeration. I put myself into difficult situations often enough, but never at the request of Herzog.”

— Thomas Mauch

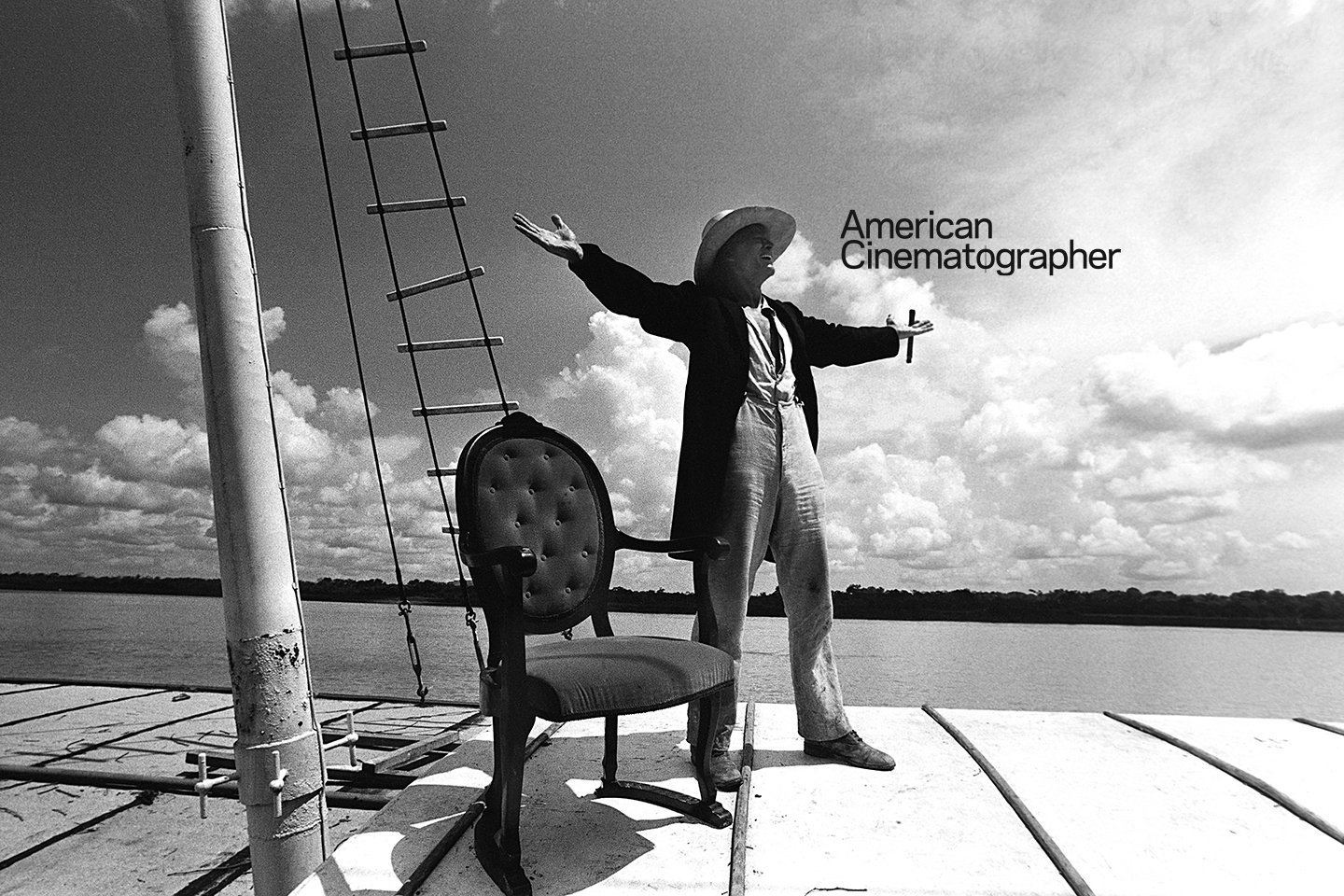

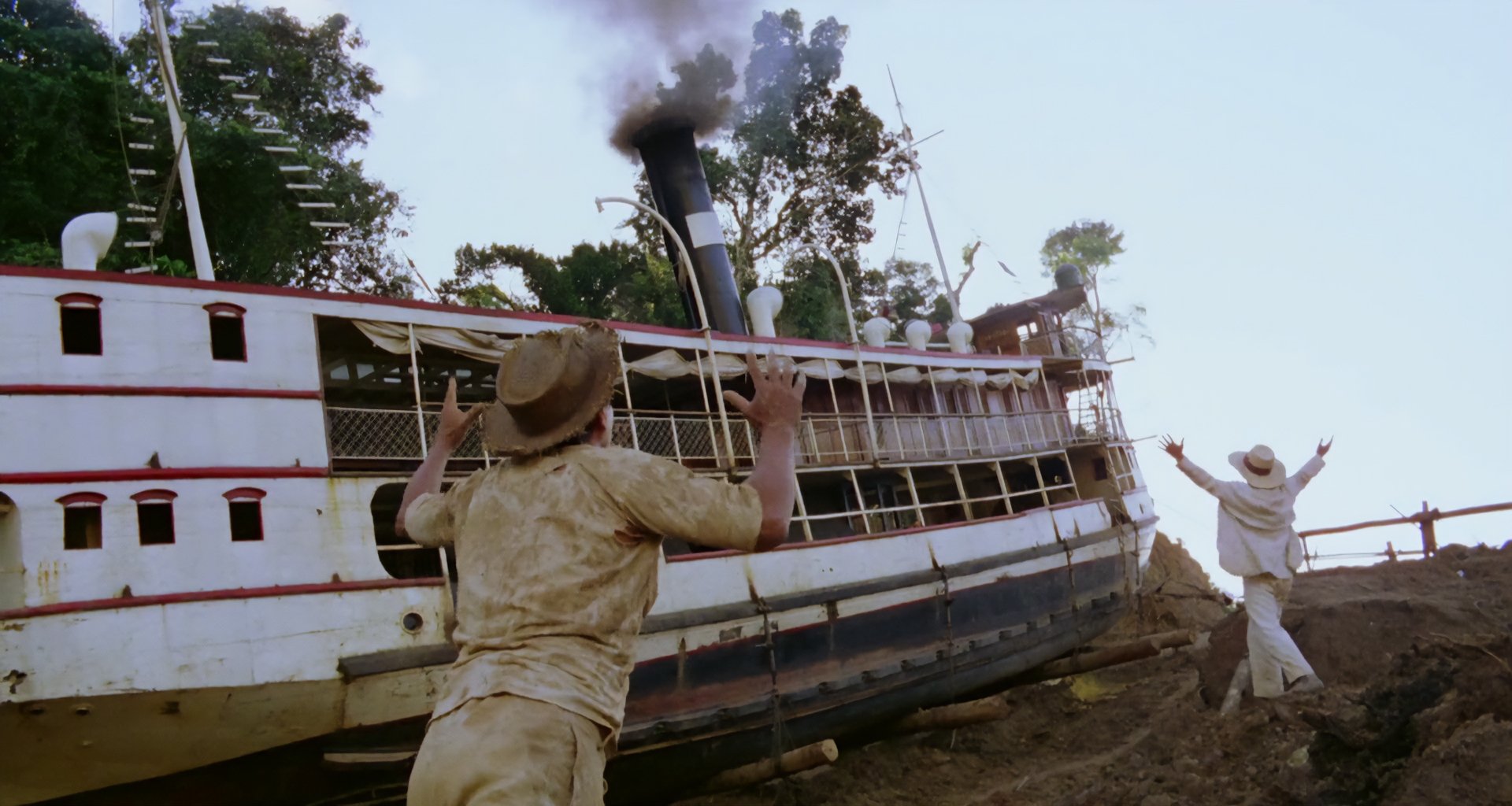

The basic story line of Fitzcarraldo, one developed by Herzog from a true story, is that of a crazed opera fan, named Fitzcarraldo, living in South America, who wants to build an opera house in the jungle. His quest to raise money for the adventure results in the idea of opening up formerly inaccessible rubber tree forests, located deep in the jungle, for harvest. Previous to this attempt, the only profitable rubber tree ventures were those close to navigable water. Fitzcarraldo “solved” this problem by locating a navigable river that came very close (on his charts) to an inaccessible inland river, with the idea of dragging a large riverboat overland from one to the other, thereby opening up the inland system for trade. He had a ship built measuring 36 meters (110 feet) in length. This is, and was for us, the beginning of the film.

For shooting we needed two ships: one to be based in Iquitos, approximately 1,200 kilometers (750 miles) from the Camisea river system and the other upstream on location. During the year before production these two ships were built. The one taken upstream spent five weeks navigating the heavy flood waters of the rainy season (without the flood waters the rivers would have been too shallow), and resting in the shallows where the crew had to wait for floods in order to move on.

This was the production’s first success. During an earlier attempt to make this picture, Herzog scouted for a suitable location in northern Peru, but the area’s Indians made tremendous demands that the production could not afford. Shortly after, the Peruvian military dictatorship fell, and the local Indians stormed his camp and burned down the production’s medical station. No film was shot.

Dealing with Indians, we learned, creates problems far beyond those we usually associate with political or cultural reasons. The loss of their identity is increasing. There are also virtually no more completely isolated areas in either the Brazilian or Peruvian jungles for the local Indians to live in. The first Indians I saw looked relatively “uncivilized,” yet many of them were wearing T-shirts with logos and English lettering on them. One had on a shirt with the Holocaust TV show logo on the front, but, of course, he didn’t know what the Holocaust meant. What then did these Indians seem to know of our culture? I had to come to the conclusion that they knew nothing but a few details, but because of their own temperament and the abrupt culture shock, nothing surprised them either. In fact, I never met an Indian that seemed surprised or showed surprise about any technology or situation that they encountered during the entire shoot. That surprised me! They had the same low-level enthusiasm for a ride in a helicopter as they did for a walk in the jungle.

The project itself was well known to American and German film companies. 20th Century-Fox was originally interested, but later dropped out. Lloyds was not willing to insure the shoot. Finally, a group of smaller British companies formed a pool to insure us. They, unfortunately, had to cover a loss which later amounted to a total of $1.5 million. The film was finally financed as a co-production of Gaumont in France, and Filmverleih der Autoren in Germany. Additional support came from the Bavarian Film Development Council, German Television, and a host of smaller organizations. Our total scheduled budget, as far as I know, came to about $5.5 million dollars, relatively low on the scale of American budgets.

Originally the film was to star Jack Nicholson, but as he insisted on a $3.5 million dollar salary, Herzog had to develop his concept with someone else in mind. Jason Robards was later hired for the title role. I recall when he landed in Iquitos he was quite shocked. Unfortunately, he became seriously ill from fever and other health problems, which necessitated his return to the States.

It was at this time that our insurance companies began to get restless, and the press began to relay back stories of this “crazy” film shooting in the South American jungles. Meanwhile, Herzog brought in Klaus Kinski for the title role. Kinski had worked with Herzog before, and they had lived through many good and bad times together. We felt that now at least we had a more predictable situation regarding talent. Still, we had to reshoot five weeks of material with him to replace the Robards footage.

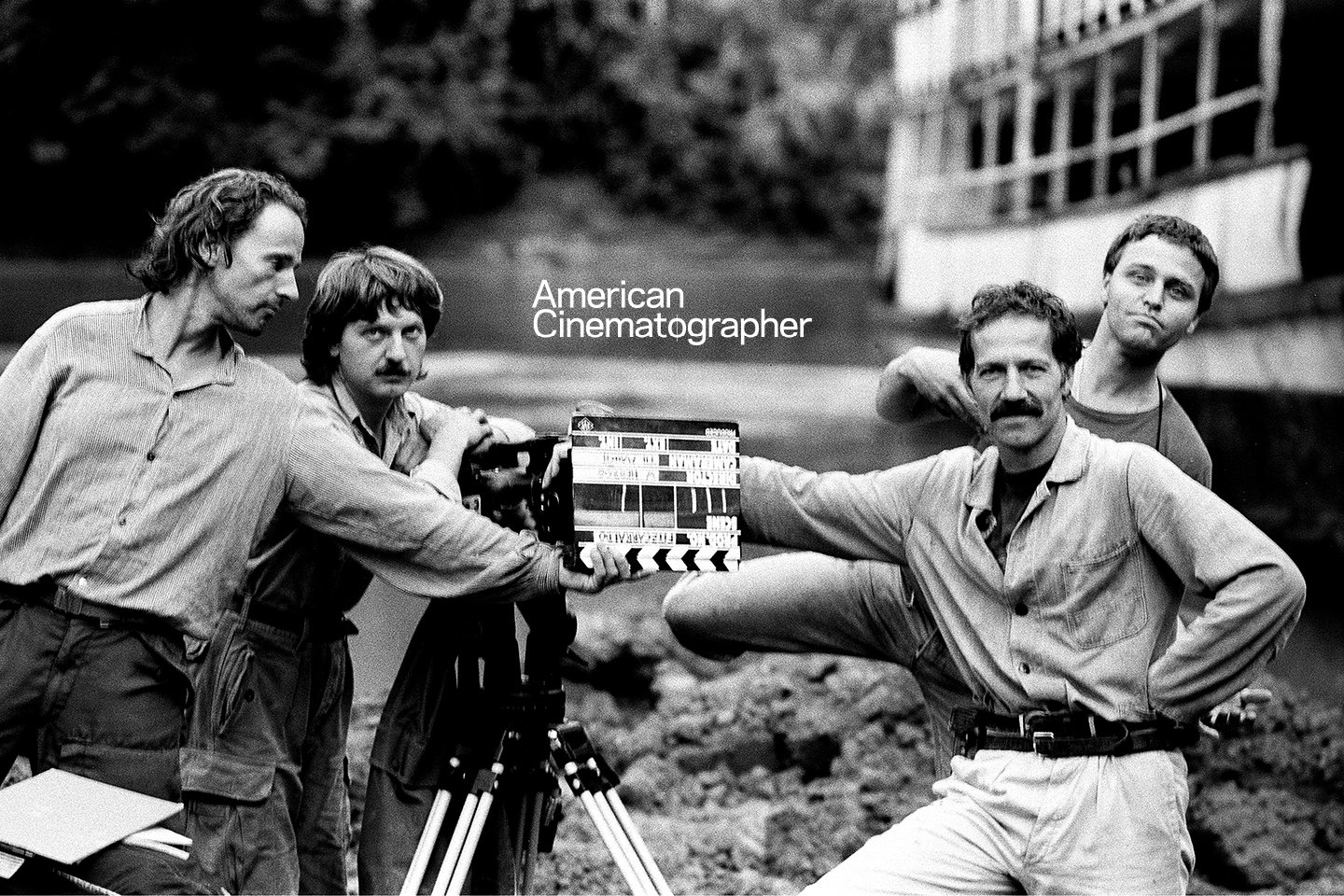

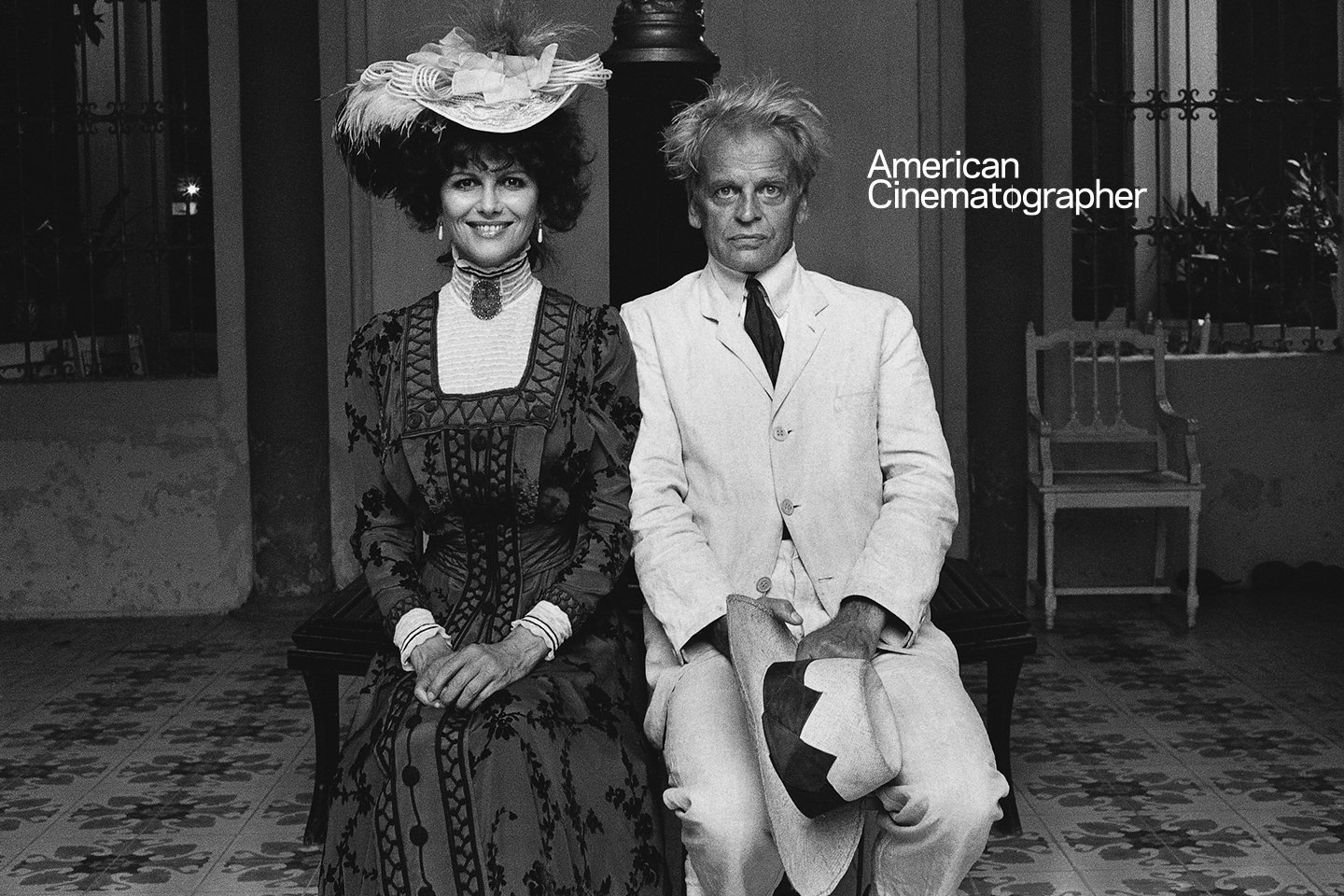

The production team was absolutely international: Herzog, as producer and director, and I, as director of photography, were both German. Our production manager Walter Saxer was Swiss, as were my two camera assistants. The sound recording crew came from Brazil, the special effects team from Mexico, and most assistants, from production assistants to 2nd and 3rd camera assistants, were Peruvians. There was another mix of Brazilian technicians that we recruited in the port of Lima. You could hear every language from Portuguese, German and English, to Spanish and Indian. The last of the changes occurred with the arrival of Kinski. Mick Jagger left the production at the same time as Jason Robards, but Claudia Cardinale, who played the role of a bordello owner and friend of Fitzcarraldo, remained. She had her own Italian assistants, including makeup.

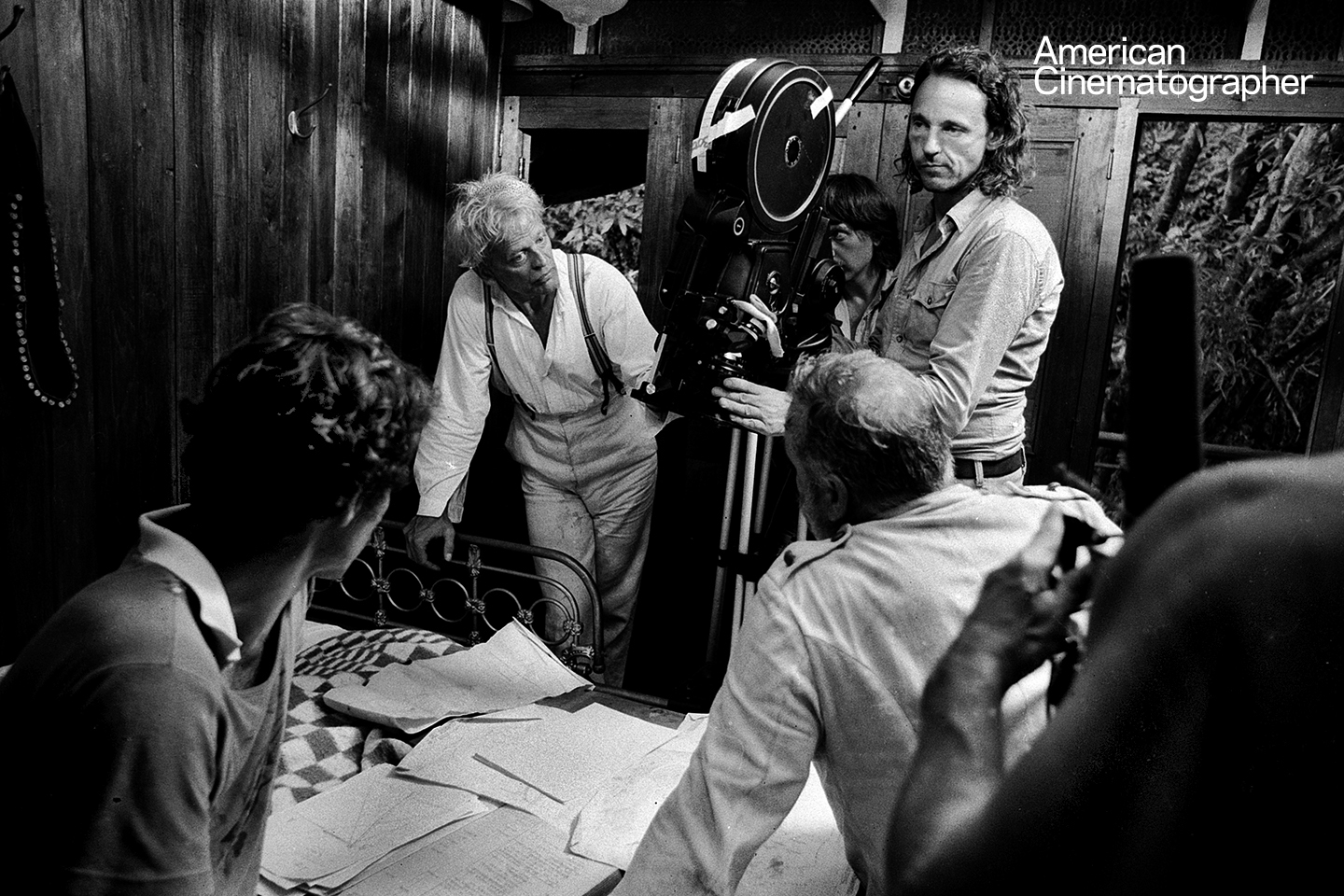

We packed in all our own camera equipment. We brought Herzog’s own Arri 35BL-2, with a set of normal Zeiss lenses. We didn’t bring highspeeds [Super Speeds], because they give a harsh, hard look that I didn’t feel was appropriate for this film. We had an additional Arri BL, several Arri II-Cs, and a variety of prime lenses. We rented two zooms in Lima, but later they proved to be terribly defective. We also brought most of our lighting equipment. I had a variety of tungsten 4Ks, and two each 2.5Ks, and 575W lamps. We also had a selection of small lamps and spots. Actually, we didn’t need much more than we had planned on. The sun there is so very harsh that I ended up bouncing light much of the time, and using all sorts of secondary reflection to light interiors. Frequently, we used only fire light or light from large oil lamps.

I had tried to anticipate certain technical problems. Certainly, I had expected it to be terribly hot, and that there would be all sorts of disease and mosquitos, and that we would only be able to sleep and work under nets. I also expected a lot of rain. In fact, both water and rain were to play a major role in the film. I was also afraid that we wouldn’t have enough light and power to make even simple exposures. None of these fears proved justified. Our elevation was about 1,200 feet, which placed us above most of the heavy ground waters, and consequently most bugs, which congregate in the lower regions.

What I hadn’t anticipated was the constant rising and falling of the river. It rose and fell so rapidly in such short periods of time, that it became difficult to film on it. Several times we hit barely submerged sandbanks, which hadn’t been there shortly before, and everything would topple over. We nearly lost our cameras overboard several times. Sometimes the water level was so low we couldn’t navigate, and therefore had to postpone shooting. Sometimes we had to change composition and lenses when navigating in extremely narrow water passages.

“Our problems in the jungle, at least as far as the cameras were concerned, were more human than technical in nature.”

Our biggest problem, of course, as it was for Fitzcarraldo, was to get the ship across the mountain. The total distance between the two rivers was 1.5 to 2 kilometers, with an upward elevation of around 150 feet. The ship itself weighed approximately 200 tons, was over 100 feet long, and clearly was not going to be moved by Indians and winches, even though that’s what the movie was all about. Theoretically, of course, moving the ship should only have been a question of “How many Indians?’’ In reality, however, it took a large Caterpillar tractor and heavy steel cables to inch this ship literally centimeter by centimeter up the hill. The whole thing had to be staged and photographed as if the Indians and winches they used were moving the ship. Actually, it all looked pretty good. The only difficulty was in staging it.

The Indians could not come into contact with the main cable, as it was very dangerous to be around. Nor could we shoot any original sound during these shots because the noise of the tractor was deafening. We were forced to record our live sound separately with the cast, as it would have been impossible to later duplicate the noise and sounds that 500 Indians make in a jungle pulling a 200-ton ship up a mountain.

So, the biggest problem faced was not in the simple making of a film, but pulling the ship up a mountain. This also consumed the largest part of our total budget. Actually, camera had the smallest budget line in the whole production: me, two assistant cameramen, two gaffers and no grips. Grip was handled by the Mexican special effects team, and a few Indians.

Our problems in the jungle, at least as far as the cameras were concerned, were more human than technical in nature. Our main camera was an Arri 35BL-2, a relatively early one that Herzog owns himself. We had a set of Zeiss normal lenses, and a rather beat-up zoom lens that I later found to be only really good from f/5.6 on. Herzog’s old 35BL-2 proved not to be the quietest camera due to its age, but it was virtually indestructible. It survived rains, floods, high humidity, high temperatures, dirt — we didn’t have a single camera problem in all eight months.

We did have problems, however, with batteries. They broke down often, but even worse was our makeshift charging system. We had a Honda generator installed on the other side of the river from us, and twice each night one of us had to row across with gasoline, fill the generator and attach all our batteries to charge overnight. The trip often ended with us in the river, as we could never get used to those small, Indian boats.

Herzog also owned a set of Zeiss Super Speeds for his BL. As I said earlier, we decided not to use them because of their cold, harsh look, and the fact that highlights or points in the background do not merely lose definition and maintain their shape when you run them out of focus, they turn into triangular points of light. An experienced cameraman can tell, in some cases, what f-stop was used depending upon the shape of that triangular spot of light. I love the older f/2 Zeiss lenses, which are sharp but still give you a softer, warmer atmosphere. This was the look that Herzog and I had agreed upon for Fitzcarraldo.

So, we had our standard Zeiss primes, and the old Angénieux zoom. Of course, as it worked out, Herzog decided to do a lot of very complicated night-for-night shots. As can be seen in the final film, we did many shots in firelight. This created a number of problems for me, most of which we solved by building and using one or more kerosene lanterns on poles, hung like microphones from a boom, and having our special effects people hold them just outside the frame. These kinds of primitive lighting devices gave us the edge in our struggle to hold to f/2, just so we could use our warmer standard Zeiss primes.

“When you work with a large group of nonprofessional actors, you must be able to adapt to any given situation or movement quickly, and remain flexible.”

The rest of our lighting was handled somewhat in the more usual fashion, with a few exceptions. We brought a range of tungsten lamps, 4Ks down to 575W. This was the usual stuff. What was unusual were the generators we had. They required eight people to move, and whenever we had to move over land, we could lose up to 1/2 day just to reposition them. On the other hand, they ran perfectly for the whole eight months, except for the fuel problem. The diesel fuel they required had to be absolutely pure. With the slightest impurities the generators would stutter, and occasionally we had to postpone production one or two days until a new supply was flown in. This also caused a somewhat irregular battery charging schedule for us. Depending upon that day’s situation, it might happen that we would find three or four batteries running short of expected power. To combat that situation, we maintained between six and eight batteries all semi or fully charged at all times, always anticipating the worst.

Interesting enough, we didn’t experience any problems with our film stock. We had Kodak 5247, and a few rolls of Fuji Highspeed. We were often asked how we cooled and stored the film. We didn’t. I felt that cooling the film while in the tropics can cause more problems than if you just leave it alone. The condensation problems alone, experienced when you pull cooled film out into the hot jungle air, were enough to influence my decision.

Night in the tropics comes very fast. One moment you’ll be shooting at f/6 or f/8, and five minutes later it’s dark. During long takes at dusk, I could see it getting darker through the viewfinder as I shot. As a result, I was forced to do a lot of handholding, as often there just wasn’t enough time to set up a tripod to get the shots Herzog wanted to capture. We had no dolly equipment at all, as it would have proved as difficult to move around as the 200 ton boat.

Of course, European DPs have always had a strong tradition of handholding their cameras. But, for this picture I decided to try out a new body mount developed in Los Angeles. I tried it, but I wasn’t happy. The only way to really see camera composition is by looking through the viewfinder yourself. The body mount’s monitor was really a compromise, especially when I panned or moved past highlights with backlight, the sun through the trees, for example. In these highlights, the monitor had a problem of image smear, or lag. In our kind of film, it wasn’t workable. When you work with a large group of nonprofessional actors, you must be able to adapt to any given situation or movement quickly, and remain flexible. This requires, at least for me, that the camera move with my body, not independently.

I had an additional problem with the body mount on board the ship. We often experienced turbulent water, but handholding the camera and being tossed around was manageable. With the mount, I was not able to maintain equilibrium, I had no natural reference anymore. The “ground” floated and shook around, the monitor image floated and shook, and then I floated and shook too. I put the mount aside, and continued to shoot as usual from the shoulder.

“We took great pains to make it look more like a documentary than a feature film.”

Our lab was MovieLab in New York, with whom I’ve worked with for the past four years. I’ve put four films through MovieLab, and I can say that they are one of the best. But getting the film to the lab was a major production in itself. It took one day to go from our location, via small plane, to the nearest large airport in Pucalpa. From there it was another 1/2 day flight to Iquitos. Three times a week, a flight left Iquitos for Miami, and there we had a man to take the film through customs, and ship it to New York. But our problems didn’t end there. Cocaine, and the widespread illegal traffic in it, made our customs transfers quite difficult. Here we were, shipping in sealed tin cans flown in from South America. Customs, of course, wanted to open the cans. Our man, after several difficult conversations, finally got them to check them, when they did, in a darkroom. The return trip of the film was somewhat easier, but Peruvian customs was a somewhat rusty operation that had to be lubricated with liberal applications of cash.

Herzog and I discussed the look of the film very little. During shooting there were many occasions where we discussed individual photographic approaches, but in general we were driven by a continuous chain of challenges and technical staging problems which we sorted out as we went along. For example, take the logistics of feeding 400 Indians out in the middle of the jungle, with the nearest mission two hours away by plane. If it rained two days in a row our little airstrip was unusable, and food had to be air dropped in. We had the additional responsibility of keeping the men “happy.” A local priest recommended that we supply several camp followers or we would have serious problems. We did so, and the women that we brought in were very nice and added a lot to our rough camp.

Photography, in general, was pretty much standard, excepting the difficult circumstances in which we had to work. In addition to Herzog’s 35BL-2, we had three Arri II-Cs. We experienced some minor problems in simultaneously composing for both 1.85:1 and TV aspect ratios between our two camera crews working separately at different locations. Some of what we shot required minor corrections later, but it didn’t prove to be too much of a problem.

The most difficult shot in the film was when the boat was to go through Pongo, the rough rapids of the river Ucayali. We covered this shot with all four cameras. I stayed on board the boat to do the handheld material with the 2-Cs. During the shooting, the ship smashed several times into the huge boulders in the river. Of course, the ship was supposed to smash into these rocks, but standing up proved to be more difficult than anticipated. The best way we found was with Herzog holding me by my belt. It didn’t always work too well, as one time I fell, splitting open my hand. Such emergencies were usually handled directly on the set. Unfortunately for me, I had to have my hand stitched up without any anesthesia, as it had all been used up after a recent major incident involving our crew and a group of Indians who attacked them. A local teacher was shot through the neck with an arrow, and our medical man did an excellent job in patching him up, but had used all our pain killers. I can say that these ten stitches were probably the worst pain I ever have experienced, but it did add to the reality of this production. Herzog was very proud that everything was so real in Fitzcarraldo, and with the exception of one scene, all the shots were real with few special effects involved.

The one major special effects shot in the film is the one where the ship finally goes through the rapids. We did as much as possible on location, but to finish we built a 10-1 scale set at Bavaria Studios in Munich. We built our to-scale boat, and created the rapids and falling water by pumping in enormous quantities of water. The scale was so large that I couldn’t get back far enough on the stage, so we opened up the large studio doors and I set up outside. I couldn’t believe it, but just then it started to snow. Through the viewfinder I could see a steaming jungle location, with river, and in the foreground it was snowing. We moved back inside, and selected a shorter focal length lens.

The end of the film shows the wild party Fitzcarraldo has with all his Indians after they had successfully pulled the boat overland to the next river. The party ends with everyone getting completely drunk. While most were sleeping the party off, the Indians cut the ship loose, and allow it to drift down the river to smash up on the rapids. They do so as a sacrifice to the River. Fitzcarraldo never understands that the Indians had accepted this superhuman challenge, without complaining, only to sacrifice the ship to their river god. It is, of course, a disaster for Fitzcarraldo, and he is ruined.

On the technical side, it should be noted that the film does not involve any trick photography, and only some limited special effects as mentioned already. We took great pains to make it look more like a documentary than a feature film. This didn’t mean that we did not use a sophisticated approach to our photography and everything else, but nevertheless we wanted it to be credible and accepted on a documentary-like basis by the viewer. For this reason, we used very little artificial light at night, and real explosions rather than special effects.

It has been said that Herzog was placing his crew and people in constant danger. This is an exaggeration. I put myself into difficult situations often enough, but never at the request of Herzog. In fact, it often happened that Herzog would say, “We won’t step on this board; it’s too dangerous; please don’t do it.” This is one area, these nasty rumors circulating about him, that needs some correction. Yes, it is true that a few Indians were killed during the film. But this was not properly reported in the press. Two Indians drowned in the river in spite of warnings from their Chief and the production not to use the river boats as we knew that they were from the highlands and were not able to swim. In spite of these warnings, they stole out in a boat which soon capsized in the rapids, and two of them drowned. This did not happen during shooting.

One time an aircraft carrying some Indians to our location crashed, and some were brought in with severe injuries. None died, however. Other Indians died of dysentery. They refused to see our doctor. In fact, they would generally only consent to Western medical treatment when it was almost too late for their condition, and they were close to death. We also had one birth, a girl, whose mother named her Molly Aida, after Fitzcarraldo’s boat. We celebrated.

Special thanks to Beat Presser for assisting AC in republishing this archival story.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.