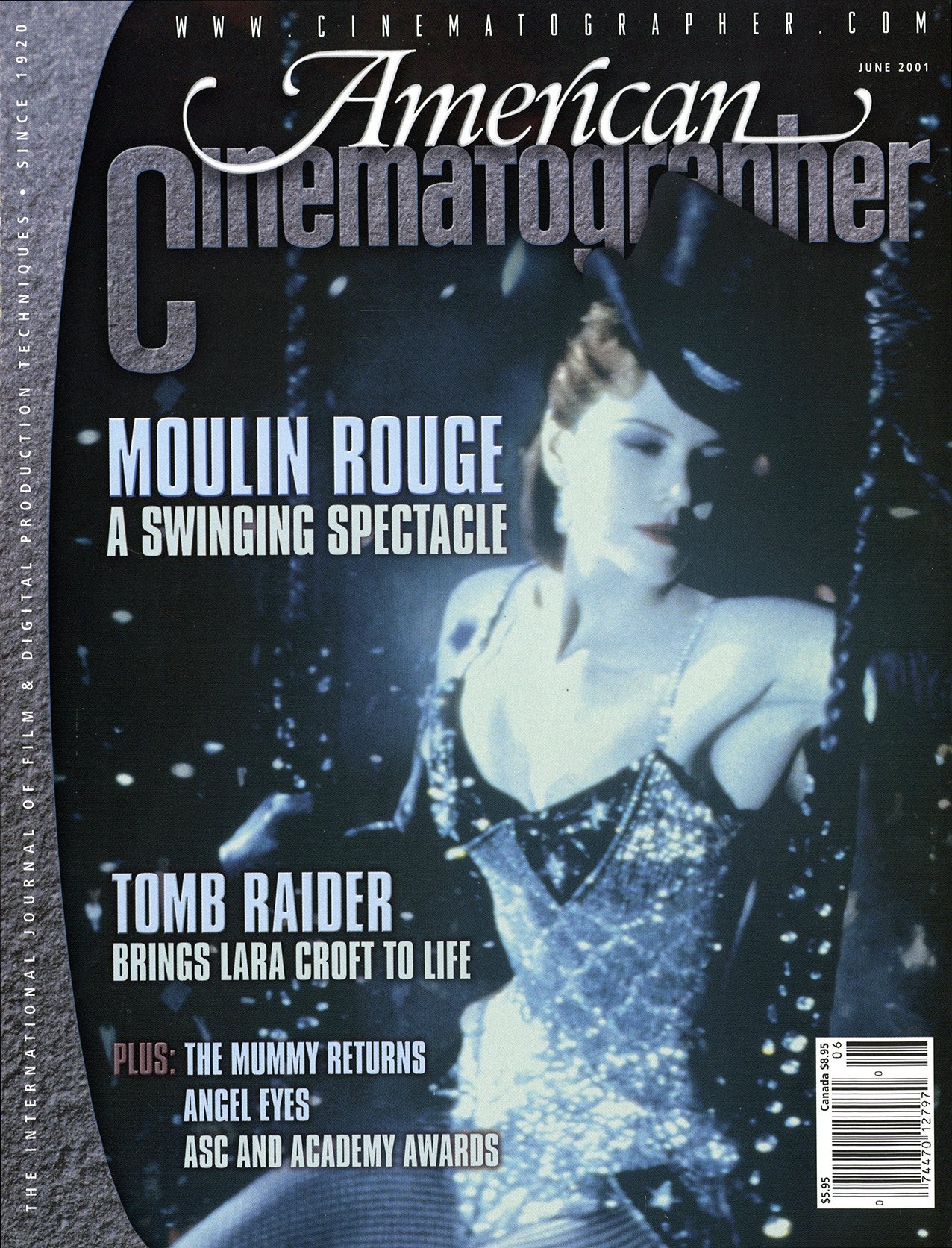

Moulin Rouge: Capturing a Timeless Song and Dance

Twenty years after its release, Donald McAlpine, ASC, ACS looks back on his collaboration with director Baz Lurhmann on this jukebox musical.

Cinematographer Donald McAlpine, ASC, ACS began his collaboration with director Baz Luhrmann on his anachronistic adaptation Romeo + Juliet: “I got this call from a guy wanting to do Shakespeare, and I was a bit reluctant. I mean, I've enjoyed studying Shakespeare throughout my life, but I've avoided making movies of his work. I'd had a few requests to do it before this, but this was just so crazy. I thought, ‘Let's go.’ So I did that film — and that led me to Moulin Rouge.”

At the time, the cinematographer was possibly best known for his work in such features as Moscow on the Hudson, Predator, Parenthood, Mrs. Doubtfire and Clear and Present Danger.

McAlpine spent a year in pre-production working on Moulin Rouge, which took the anachronistic element of Romeo + Juliet even further — set in 1890s Paris to the tune of contemporary pop songs from the likes of David Bowie, Fatboy Slim and Madonna.

For McAlpine, “My collaboration with Baz was great from day one. I found very early in my career that the most difficult, but most rewarding, thing you can do is decide what you can offer the director, and what you can take from the director. Every director is different and every situation is different. If you go in and do what you did on your last movie, it’s probably not going to work on this movie. Every director I’ve worked with is different — that’s part of the business, figuring out who they are and what they want from me.”

An integral third partner in the pre-production process was production designer Catherine Martin. “She became a massive interpreter of Baz’s ideas and her own ideas,” McAlpine says. “For both films, Romeo + Juliet and Moulin Rouge, she would make these fantastic graphics on the computer of a scene from the movie. The costumes would be near-perfect. The characters had the right expression. They were incredibly useful because it also gave some concept of how the lighting should be set up. It was a great shorthand to see through her what Baz really wanted. The work she produced was really unbelievable.”

Clear communication and collaboration was evident from pre-production onward: “It was an absolutely exhilarating experience. I mean, the three of us, Catherine, Baz, and myself, really did intermingle, really did communicate and participate together. I never felt that I was just the cinematographer there to photograph the project, but I was part of the team. That’s a good feeling.”

Almost the entire film was shot on stage, using elaborate scaled sets of the Moulin Rouge club in Paris built for the film. The only shot taken on location was used as a plate for a greenscreen effect — the view outside a carriage window (itself filmed on stage).

Relying mainly on practical effects and production design, McAlpine created an opulent visual style, shooting in anamorphic with Panavision Primo lenses paired with Panavision Millennium cameras and Kodak 500 T 5279 film stock. For handheld and Steadicam work, C-series lenses were used. “We shot in anamorphic to make it look more grand,” he says. “In the days of theatrical exhibition, when the screen goes out just that little bit further, the audience tenses up a little bit. Visually, I just wanted it to be extreme. Framing wise, I wouldn’t call it conventional, but it isn’t excessive. The lighting, the color, the performance, and the coverage, certainly was extreme and had massive energy. I mean, the energy in the film is fantastic.”

McAlpine wanted to steer away from the traditional, proscenium-style approach of watching the dance numbers. To capture the frenetic energy he desired, he used multiple cameras and many takes: “Most of the musical numbers were shot with four cameras. We might shoot four or five days on one number. I tell you, having listened to [the Police song] ‘Roxanne’ for about four or five days, there was nothing better than getting home and putting a pillow over my head. It was amazing. I would have these four cameras, I would get four setups, we would do two or three goes with the number. Then I get another four setups and then I'll get another four. Now the fourth set was just endless, endless, endless coverage from predetermined situations, most of which I had to find because everyone else ran out of ideas. I mean, we always had a theme in the back of our heads. But many times the third and fourth camera had a very weird position, mainly because they'd be out of the shot on the other cameras, and they would actually get some of the greatest shots of the performances because it wasn't a predicted situation.”

In contrast to the dance numbers, most of the drama was shot single-cam. A large focus was put on maintaining energy throughout. “We shot an unbelievable amount of coverage,” McAlpine says. “You have to if you're going to participate in that kind of production. Whenever the performers were rehearsing, Baz and I were trying to find the best way of shooting the sequence. What’s the best way to photograph this? How can we get the most energy?”

While Moulin Rouge was an immensely elaborate production, McAlpine was not phased by the scale. “Of course, at one level, I could say in my ignorance I never realized there was a problem,” he says. “That’s sort of been the concept under which I've worked. There’s always a solution to the problem. Just put your mind to it. Get down there and do it. Most of the technical challenges — you just go work them out. They cease to be a challenge very quickly. I really believe I looked at most of them as an opportunity more than a challenge.”

The film was finished photochemically in Australia and color timed between Australia and Los Angeles, where Lurhmann and McAlpine were at the time, respectively. “The timer would start a reel in Australia and we would watch in two different theaters on other ends of the world,” the cinematographer remembers. “It’s sort of amazing that the film was timed in just four passes. They would have to reprint the whole thing between passes and have the new prints flown over to us for review. And over a period of about three weeks, we actually finished color timing the whole project from two sides of the world.”

Looking back on Moulin Rouge 20 years later, McAlpine cites his crew for the film’s success: “Steve Mathis was my gaffer and Patrick McArdle was the first AC. Both have been with me for most of my American career, and, from my point of view, on the camera side and with lighting, I've got to take a fair bit of the credit that normally goes to me and give it to them. I’m proud I did the film. Often, looking back at these previous endeavors, you wonder how you did it and what would you do if you had to do it now. There’s probably two movies, which I'm not going to mention, in which I didn't go home feeling satisfied or rewarded, out of 60. That's not bad. Not bad at all.”

Moulin Rouge has recently had a successful reimagining as a Tony Award-winning Broadway musical. While McAlpine was not involved in the stage production, he is excited that the story is finding new avenues to reach audiences: “I'll be there on opening night in Melbourne. It will be great to see — I can see how they’ll do it too.”

McAlpine was honored for his camerawork in the film with Academy Award, ASC Award, ACS Award and BAFTA nominations, winning Best Cinematography from the Australian Film Institute. In 2009, he was honored by the ASC with its International Award for his exceptional body of work.

His subsequent films have included The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe; Ender's Game and Ali's Wedding.