Problem Solving on Terminator: Dark Fate

Storytelling amidst a sea of technical details is a test for every cinematographer, but this sci-fi sequel took the dynamic to a new level for director of photography Ken Seng.

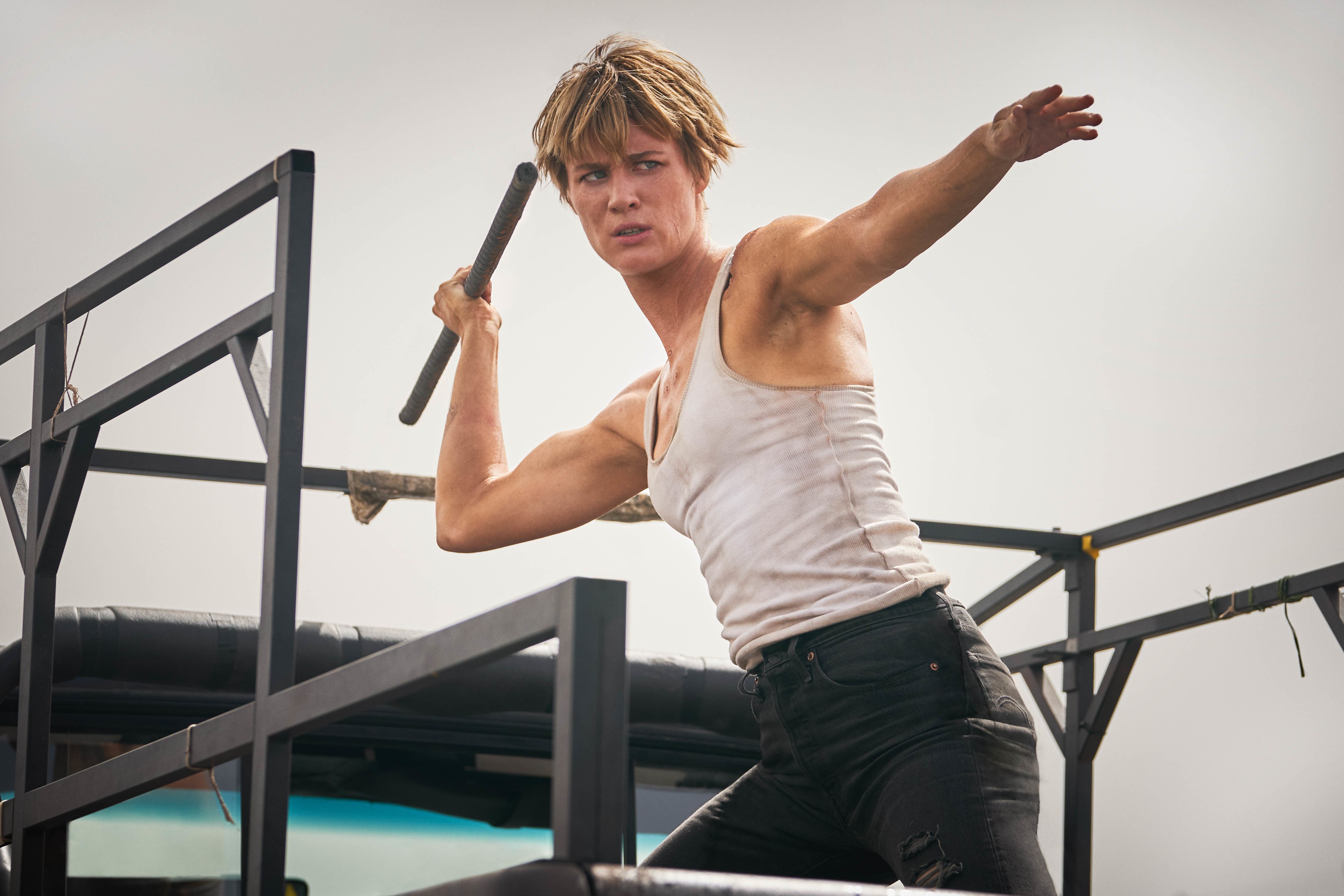

Unit photography by Kerry Brown, courtesy of Paramount Pictures

Making a Terminator film is often as much about confronting a legion of technical and logistical challenges as it is about facing off against killer robots from the future. This tension is mirrored in the story itself: a time-spanning tale of the struggle between humans and machines.

Photographed by cinematographer Ken Seng, Terminator: Dark Fate is the sixth time this story is being told, but according to the filmmakers — including director Tim Miller and executive producer James Cameron — Dark Fate is a direct continuation of Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991; photographed by Adam Greenberg, ASC; who also shot the 1984 original), in which heroine Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton, returning) averted the Skynet AI’s nuclear holocaust. However, the timeline branched off into a grim future where another malevolent AI called Legion sends its own version of a Terminator (Gabriel Luna, the “REV-9”) back in time to Mexico City to assassinate the leader of the human resistance, Dani Ramos (Natalia Reyes). Meanwhile, the resistance has sent back a protector, the augmented super-soldier Grace (Mackenzie Davis). Sarah, Dani, and Grace cross paths before a series of mysterious text messages leads them to Laredo, Texas, where an aged Terminator named “Carl” (Arnold Schwarzenegger) — the same T-800 responsible for murdering a teenaged John Connor (Edward Furlong, in a motion-capture performance) shortly after the events of T2 — lives with a surrogate family. Its mission complete and experienced enough to feel an AI’s approximation of regret, Carl agrees to help Sarah with her mission to protect Dani.

This is the second feature collaboration between Seng and Miller, following Deadpool (2016). That film also featured a large number complicated effects and stunts, but, being a Terminator film, Dark Fate presented a whole new level of technical hurdles.

In two lengthy phone conversations with AC, Seng offered insight on this rigorous process.

American Cinematographer: In tying this film into the first two, was it important to honor an established visual style?

Ken Seng: Absolutely. Tim and I felt like we had to strip some things away from the way the last few films were made to make things feel a little more raw, a little more natural, a little more believable, especially in the first two acts. The Cameron movies were very grounded visually, the characters were real people that crazy shit was happening to — and in his execution it didn’t seem absurd or farfetched.

What do you mean when you talk about stripping it back and getting more real?

One of the main things that we wanted to do is shoot on older anamorphic lenses to give the film a messier, more human, aesthetic. I frankensteined together a set of Cineovision and Xtal Xpress anamorphic lenses from ARRI Rental in Europe that to me felt imperfect, raw, and real. Also, in the beginning of the movie, in Mexico City, we wanted to be handheld on a long lens so you really felt like there were foreground and background layers of lively Mexico City in all of the shots with Dani. In her house, we tried to make all the lighting feel practical, and let people go dark in certain areas. We needed to establish her home life and her family — that she’s a real human being — because that gives us license to do the rest of this big action movie; if you don’t have empathy for the characters the audience stops caring.

How does the visual language change when you get into the action sequences?

When we get to the factory and Grace fights the REV-9, we wanted to give the camera this very robotic quality, like it was locked onto the Terminator’s movements; we also wanted the camera to whip with the action and stop hard when someone slammed into a wall or the floor so there’s a sense of inertia and weight to the movement. It was critical for Tim and I that the REV-9 and Grace felt more powerful than anything human. They needed to embody superhuman power and weight. We purposefully accentuated the impact during these fights with hard pan and tilt stops using the extra frame space left in our 8% overall frame reduction. It’s hard to get a big camera to stop as quickly as we wanted it to. When a human or a remote head pans a camera we can’t stop on a dime, it’s always padded out a little. We wanted to change that, and I feel like the scene stands out as a result.

What camera did you use to shoot the project?

We were going to shoot with ARRI Alexa 65s but then I realized the Alexa LF can go up to 150 frames per second at 4K. Also, compared to the previous versions of the Alexa, the LF’s sensor rolls off better in the highlights, has more detail in the heel, and there’s a beautiful edge focus fall off that’s unique to large format.

Any other lenses?

For the personal, heart-wrenching scenes I used the Cineovision and Xtal Express anamorphics, and the bigger action set pieces I shot with the Master Anamorphics. For all of the flash-forward future work we used some of the custom ARRI DNA primes that Bradford Young [ASC] created for Solo, as well as some of the lenses that Robert Richardson made with ARRI. I was fortunate enough to build some of our own custom lenses as well. My favorite was the 35mm DNA T Series we made that has lots of edge fall off used for the subjective flash forward POV’s. We also had a bunch of standard DNA lenses and some T-type DNA lenses with customizable irises, which we used to get a square bokeh. I wanted the flash-forwards to feel subjective, which is why I went for that edge fall-off you get with DNA lenses pinned all the way to the corners.

By “pinned to the corners” do you mean wide open?

I mean trying to maximize the image circle on the sensor. I did that with the Master Anamorphics, too. They cover more of the sensor than the other 2x lenses we tested, and we pushed our frame line as close to the edge of the sensor to really maximize the fall-off and utilize the most resolution possible.

What resolution did you capture?

I had to sell my decision to shoot the film in anamorphic with the LF, because people were a little hesitant about the camera’s effective amount of pixels. Everyone talks about topline resolution, like the picture has to be 4.5K pixels across the top in order to be 4K. For this film, we started with an 8% reduction in the frame in case visual effects needed to stabilize shots or create heavy robotic camera moves, so the LF in full gate anamorphic mode gives you a square negative that ends up being 3,698 by 3,096 pixels. Some people will look at that number and say it’s only 3.6K, but the total resolution works out to about 7.6 million pixels. When you shoot 4.5K spherical, the frame lines would be 4,448 by 1,862 pixels. Some people would call that 4.5K, but, in reality, it’s only 7 million pixels per frame.

Did you test different cameras?

I did tests with the Alexa 65, Alexa LF, Sony Venice and Red Monstro. It was all about dynamic range and the feeling the images conveyed. I also wanted to look at detail, what it looks like when you zoom in on hairs and things that were backlit. We put all these cameras up against each other and looked at them in a DI suite with our colorist Tim Stipan at Company 3. To me, the LF sensor just looked the best. The Venice was comparable, but you can really dig into the LF’s ARRIraw negative in a way that sold me for this film.

So when you say that it’s hard to get a big camera to move the way you wanted…

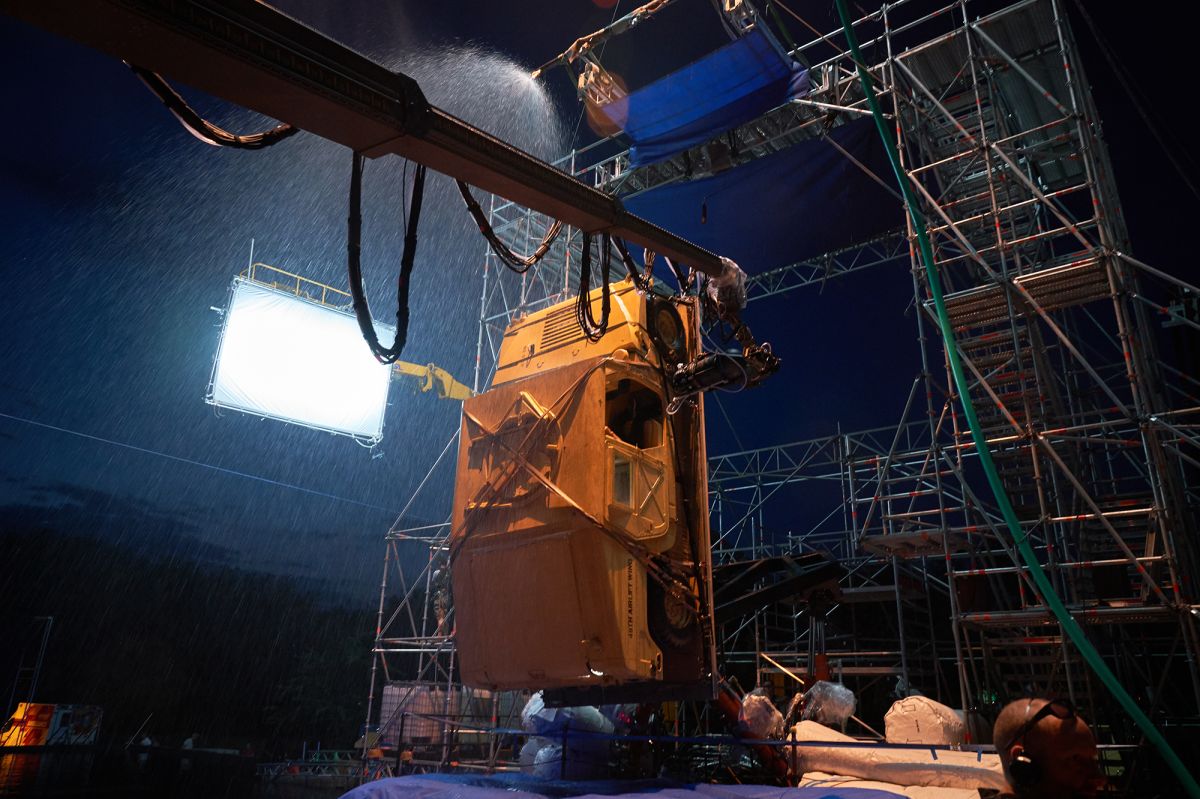

The LF isn’t as big as an Alexa 65, but it’s still a big camera. In order to move it that fast, we ended up using a Scorpio 30’ crane or a MovieBird 45 with a Matrix gimbal. This was my first time working with key grip Guy Micheletti, and the interesting thing about Guy is that he likes to key from the dolly or from the crane. He put a wand on the crane and just walked with it everywhere operating the pickle himself. He’s right in there with the action, moving the camera super fast. He’d wear a full-face mask and lead body suit when we usedsquibs or full loads in weapons. It was awesome, but it was strange for me to see a key grip on a $200 million movie keying from the dolly.

Where are you used to seeing them?

Next to me at video village, or delegating from floor. But Guy just wanted to be in there with our A camera and Steadicam operator Christopher McGuire. We used HME wireless communications systems to stay in constant communication regardless of our location on set.

“It was amazing to plan out something this big and complicated on paper, then make it happen in real life.”

Let’s talk about the first big car chase set outside of Mexico City. Where did you actually shoot it?

Murcia, Spain. I really love that part of the movie.

It’s a hallmark of all the Terminator films — you need to have a huge chase sequence. What was yours and Tim’s approach for this one?

For me, it all comes down to empathy and telling a story about real human beings. We wanted to tie all the destruction and the fear and mass and inertia back to Dani and her brother Diego [Diego Boneta]. But also, it was amazing to plan out something this big and complicated on paper, then make it happen in real life. I remember working on the previz with Tim and we were thinking, “what if the front plow of the REV-9’s dump truck plows four cars out of the way as it bears down on our heroes?” And all that stuff was real and we built this big cowcatcher out of steel pipe to hit vehicles and fling them into the air. [The plow was added in post.]

How much of the action did you shoot yourselves, and what was turned over to the second unit?

The main unit spent two weeks on the highway, doing everything with the characters and the REV-9’s truck in the same frame. Our goal was to tie our actors into the action, then second unit cleaned up for two weeks, getting shots of the dump truck hitting other vehicles and blasting through the center lane. Tim and I collaborated with second-unit director Phil Silvera to come up with a rough game plan. We knew what the A and B cameras were going to do for every setup, and then oftentimes the C and D cameras were just bonus to see what we could get from putting them in dangerous situations.

There was a lot of geography to cover, and every day we’d start in a different part of the highway. One of the best tools out there to keep actors in the middle of intense and visceral action car work is a pod car — a detached driving console you can put on the front, on top, or in back of the picture vehicle — and we would rig a bunch of cameras looking at the actors while they went through high-speed close-quarters driving choreography and we could fake hitting a guard rail or another car. Another incredibly efficient tool we had for main unit actor work was a camera car with a 30’ Technocrane riding in the back bed, which we used to tow our hero car and whip the A camera around the vehicle while it moved through the high speed driving choreography. Additionally we got great stuff with the B camera operated by Laszlo Billie on a long lens, mounted to a slider on the back deck.

How much of this sequence was done practically?

We tried to do practical stunts as often as possible, but it was always our plan to clean up that sequence on stage if we had to, so we made sure to get multi-camera array plates for everything. We did a handful of bluescreen shots in Budapest, where we did all of our stage work at Origo and in Fót.

One of the cool things about The Terminator and Terminator 2 is that they don’t feel like stage movies. We wanted to honor that tradition. Maybe it feels like a bit like a stage once we get to the C-5 crashing and flipping around in the air, but all the VFX work is really impressive. We could have a whole separate conversation just about that.

Let’s do it.

We had to do really tight previz for that sequence because it’s all wire work with actors in an enclosed space. We built three separate C-5 sets, one which we used for most of the action on the runway and takeoff, another set that could rotate 360-degrees, and a vertical set.

My assistant [to the director of photography] Nick Turner made incredible previz breakdowns that showed the roll axis and tilt inclination of the airplane and where we’re at in the sequence. You have to methodically break it down and commit early on. A DP on a smaller movie could maybe change things on the day, but not on something like this, because the camera rigs have to be vetted by special effects and visual effects. You really have to engage with your effects departments and do incredible amounts of homework so you always know where you are in the scene and not lose sight of the storytelling in a sea of technical details.

I understand the C-5 set used one of the largest gimbals ever for a film production.

Five massive gimbals were used on this movie. [Special effects supervisor] Neil Corbould has so many huge movies under his belt, so I could just go into his office on my own and say “I don’t understand this process.” And he would say, “we have a designer who works with our department. You should sit down with them and figure out where all the lights go, and by the way this whole set is going to roll in multiple directions, so you’re not going to be able to plug anything in.” We needed months of pre-planning to know what lights were going where, and we needed precise control over all those lights because they’re always flickering and changing in a specific progression throughout the scene. So gaffer Brian Bartolini and I sat down with special effects art designer Stuart Frossell and we decided to build SkyPanel 120s built into the fuselage, 2’ Quasar tubes in the lower section, and LED Kino Flos in the top for the red emergency lights, needed fill, and ambient light. A lot of the fixture choices were about what’s the right size that’s LED, wirelessly controllable, and not with DMX, because all the power had to be on a slip ring.

I saw a Bolt motion-control rig in one of your behind-the-scenes photos. What’s going on there?

Sometimes our cues needed to be super-precise, so we needed a rig that would move fast and wasn’t as susceptible to inertia as a Moviebird or a Technocrane.

It looks kind of like a Kuka robotic arm.

It’s consistent, safe, and fast — you know you're going to get the results you need every time. Our Bolt was prepped about a week before we started shooting and we’d typically look at the moves the day prior, in case we wanted to make any adjustments. Jason Snell from ILM mapped the Bolt’s software perfectly with our previz.

What’s an example of a shot where you used the arm?

There’s a super-complicated one-r where the Humvee is flying through the air and Sarah sees this out-of-focus fireball in a rear-view mirror, then we rack focus to the burning C-5 careening towards us as the flames become the primary lighting source, then the camera wraps around to the back of the Humvee to reveal Grace hanging off the vehicle platform while the C-5 plummets toward the ground in the distance. We wrote a program for the Humvee gimbal and a program for the Bolt, then mimicked the burning C-5 with a bunch of Color Force 2s on a 40’ truss that descended past the rear quarter panel of the vehicle and landed perfectly on Grace.

“Doing a movie of this scope and scale teaches you so much. I had to ask so many questions going in. I had to be humble and open-minded, and really take a back seat to the machine before learning how to drive it.”

Was everything automated at this point?

There were times when we used Q Take to cue all the elements and times when the SFX gimbal control, Bolt Motion control system, and dimmer board operator Josh Thatcher had to instinctively wing it. Maybe it’s cool to say that we tried to automate everything, but we ended up going old-school for the lighting because we just trusted our board op Josh, and the rest of the crew to nail it every time.

What can you tell us about your collaboration with visual effects supervisor Eric Barba?

I learned a lot from him and one of the really cool ways that we interfaced was for Grace’s arrIval, when she falls from the overpass and these two Mexican teenagers find her. It was always going to be a bluescreen set with practical elements — because Mackenzie’s naked for this whole scene and it was going to be a closed set — but it started getting cold in Budapest, so I asked if we could just shoot it on a stage. And Eric was like, “absolutely, we can make it look real.” He showed me some scenes from Zodiac, which he supervised, and you would have no idea were shot on bluescreen at all.

Like the scene where they investigate the taxi driver murder scene?

That’s the one. And I was like, “Okay, now I have more freedom to light the way I want to, with much less work for the crew.” We decided to make this big gravel parking lot on an Origo stage with two light posts and berms around the perimeter, just high enough to hide the ground row SkyPanel S60s we had uplighting the bluescreen. We also drove cop cars onto the set, and had to shoot almost 360 degrees.

How did you light it?

From one side with a heavy 5:1 ratio, because I needed to keep Grace’s body in the shadows. I also like to do color temperature mixing, so for all the night work in the movie I would have Lee 728 Steel Green as a base ambience between 3-4 stops under and then I would have the Lee 651 Hi Sodium key lights generally at a half a stop under, almost like I was shooting film but with slightly more latitude. We ended up using SkyPanel S60 space lights because they just hang as these clean cylinders and that allowed us to accommodate the stunt rigging. One of the hard things about this scene is that I really wanted a plate unit go to Mexico City, but we never got around to it. Instead, I told Eric I wanted sodium vapor lights, I gave him my contrast ratios and he had his concept people rough in the environments, so that I knew what the backgrounds would look like by the time we started shooting. At first, I was super skeptical. We were on a small stage and the bluescreens are a little closer than I’d like. But it totally works. Eric’s got an Oscar, he works with David Fincher, he works with Joe Kosinski, so you gotta give a guy like that the benefit of the doubt.

Were you able to monitor the backgrounds on set in real time?

No, we just had to plot everything out. We were kind of under the gun because it was a last-second move to shoot the scene on stage, but we coordinated things well and luckily our set met with another stage that shared a garage door, so we were able to drive the cop cars right in. I’m still amazed when I watch that sequence to think that it was all bluescreen.

The de-aging effects for Sarah and John Connor are also remarkably seamless. How did that process affect your work as a cinematographer?

Our approach was to use younger body doubles for the 1990s versions of those characters on set, and then Linda and Ed did performance capture so we could replace their faces in the same lighting environment. In my work at Blur as a visual consultant for their video game cinematics, I’d noticed that staying out of direct sun seems to give the best results for photorealistic CG human skin, so we decided early on to have this scene happen under a cabana, where the characters would be in shade.

Why is it better?

There’s something about the reflective quality of specular light on real human skin that’s difficult for computers to recreate. It comes down to shading, translucency, and texture. The whole scene felt risky when we were doing it, because this was the opening of the movie and if it didn’t look real we’d lose the audience. ILM loaded in video of every movie that Linda and Edward were ever in — every single frame of them, to teach this AI software to know who that actor is, and to recognize them whenever they see them. So, every time Edward turned his face, the program’s real-time tracking software would go through every possible image of him and come up with frame by frame a match in this little window for the CG animators to use as a reference.

What can you tell us about your collaboration with colorist Tim Stipan at Company 3?

Tim Stipan and I went to film school together at Columbia College in Chicago, and we had a great experience with Deadpool, so Tim Miller and I were happy he was available for this film. After we shot our first round of camera tests, he came to the Company 3 office in London to help us create our show LUTs.

What was the purpose of these LUTs?

I wanted to light the film a little darker than your typical Hollywood blockbuster and having the insurance in the negative was important to me. We typically used a half-stop overexposure LUT and we also created a one-stop overexposure LUT. I try to get the dailies as close to the finished product as possible. Our DIT, Jay Patel nailed everything, but then in my back pocket is some extra detail if I need it later. It also helped visual effects to have a dense negative. It goes against my instinct to over-expose a digital negative, but in this instance is served us well for multiple reasons.

Where did you do the final color? What kinds of adjustments are you making in the DI?

We did final color at CO3 in Los Angeles. It’s a commercial film, but we also wanted to take an artistic approach. Tim Stipan has done the artistic indie films with me, and he’s also done the big Hollywood action movies with me, so we’re able to reference our past work in terms of how far we push things. It has to walk a line, and he understands the aesthetic that I’m going for. When new shots come in and I can’t be there, I can be sure he’s going to do something similar to what I’d do because he’s been with us from the first camera tests, he understands the longterm vision, and he knows what I like.

I imagine that the color grade helps to further tie all of your visual effects together.

Tim Stipan is really good at doing all of the subtle little things that make the composites look great. On a movie of this size you have vendors from all over the world turning in visual effects shots from various sequences, so a big part of the DI is taking that footage and making it look cohesive. That’s why it’s so critical to have a colorist who understands the vision of the film.

After making a film as technically complex as this one, do you feel like you can pretty much tackle anything going forward?

Doing a movie of this scope and scale teaches you so much. We shot on huge stages, against bluescreen, in the woods, in the desert; we shot aerials, we shot underwater, we shot motion control with spinning gimbals and a massive 20-minute car chase. I had to ask so many questions going in. I had to be humble and open-minded, and really take a back seat to the machine before learning how to drive it. I love being humbled by the process. I hope I never lose that.

TECHNICAL SPECS

2.40:1

ARRI Alexa LF

Cineovision, Cooke Xtal Xpress, Zeiss Master Anamorphic primes; ARRI DNA spherical primes

Digital Capture

VFX Supervisor Eric Barba

“Collaborating with the cinematographer has always been a primary focus for me. It’s my job to make sure the visual effects not only match the director’s vision, but the look and feel of what the DP is after.

“Ken and I talked at length about what we needed to do on Terminator: Dark Fate. He was very supportive of visual effects needs, and together we made sure we could make sequences like Grace’s arrival work: I explained my desire to only shoot on bluescreen, and how using the bluescreen would give us the best overall look, especially with the skin tones of our actors. Ken and his crew were very helpful, and that lead to what I hope is a pretty seamless sequence. We also used different shutter speeds to help enhance the image quality of what the visual effects teams would be working with, and then those teams would add back in the motion blur in post.

“For the opening flashback sequence where we needed to bring back a T2-era Sarah Connor, John Connor, and T-800 Terminator, I requested that our witness cameras be the same cameras as our main unit: Alexa LFs. Normally other cameras are used for VFX witness, but given the way we were going to use the footage and how complex the work was going to be, I felt we needed the same cameras — all timecode synced — to make the head replacements work. It meant that Ken’s crew needed to support the extra cameras, and that we would need them ready to go for all head replacement shots. Not a trivial feat, but one that would help ensure that our head replacements would hold up on the big screen. This is a great example where the camera department became a crucial part of the visual effects process, a similar plan and process used on Tron: Legacy and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.” — Iain Marcks