Ray Harryhausen Talks About His Cinematic Magic

After more than 40 years, the wizard of stop-motion cinematography finally shares some of the technical secrets of his unique artistry.

By Ann Tasker

[Editor’s Note: This discussion was part of AC’s coverage on Clash of there Titans, with an overview of the film’s production found here.]

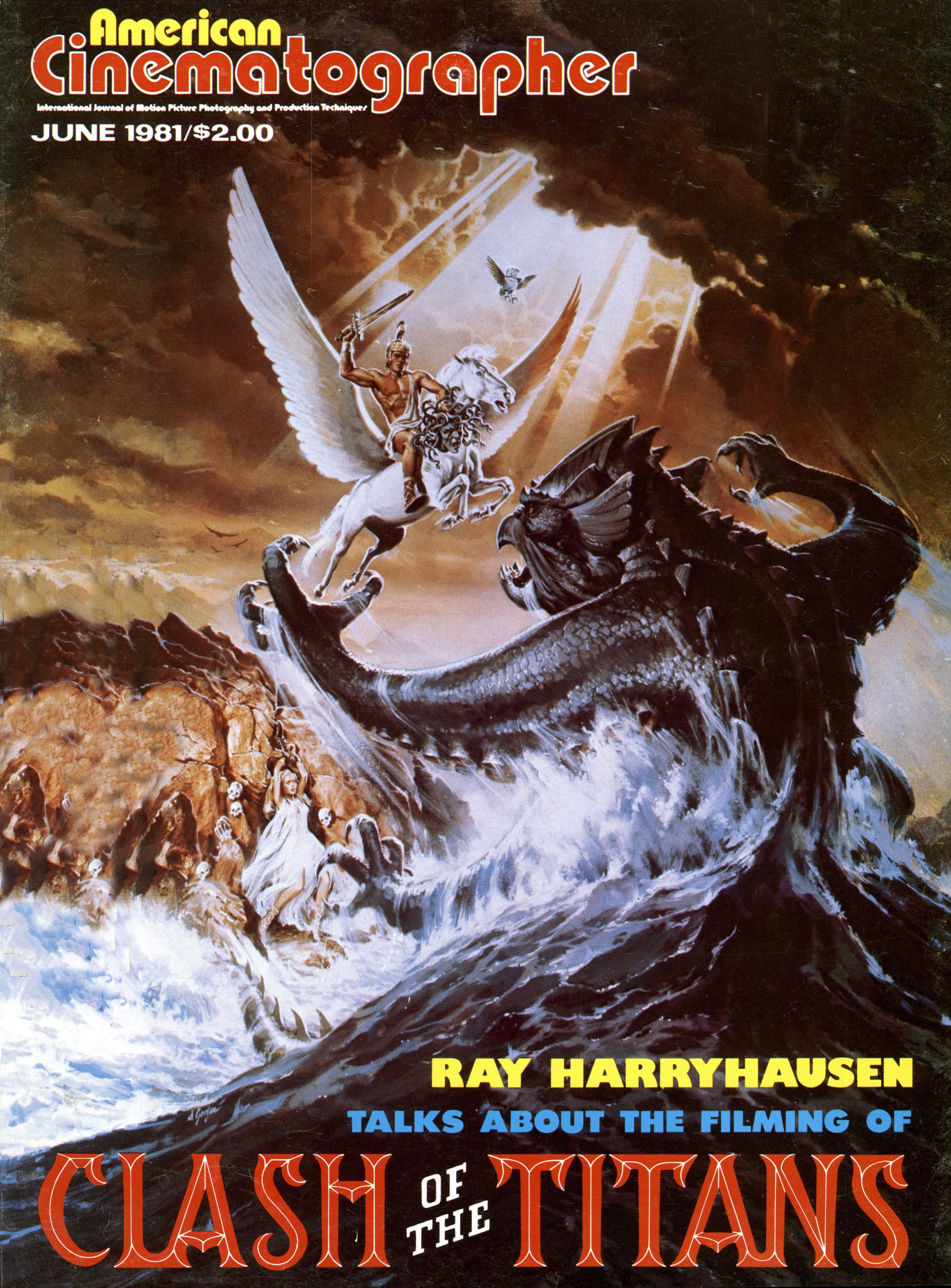

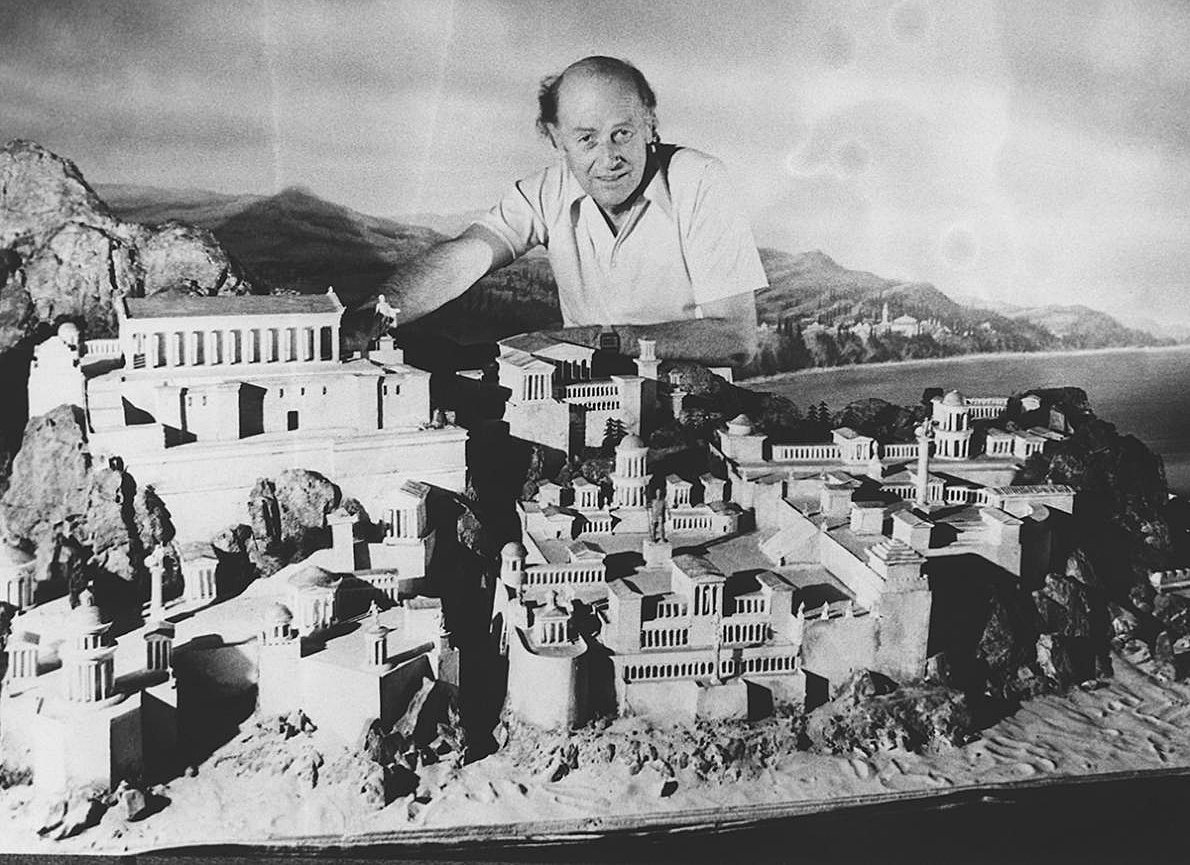

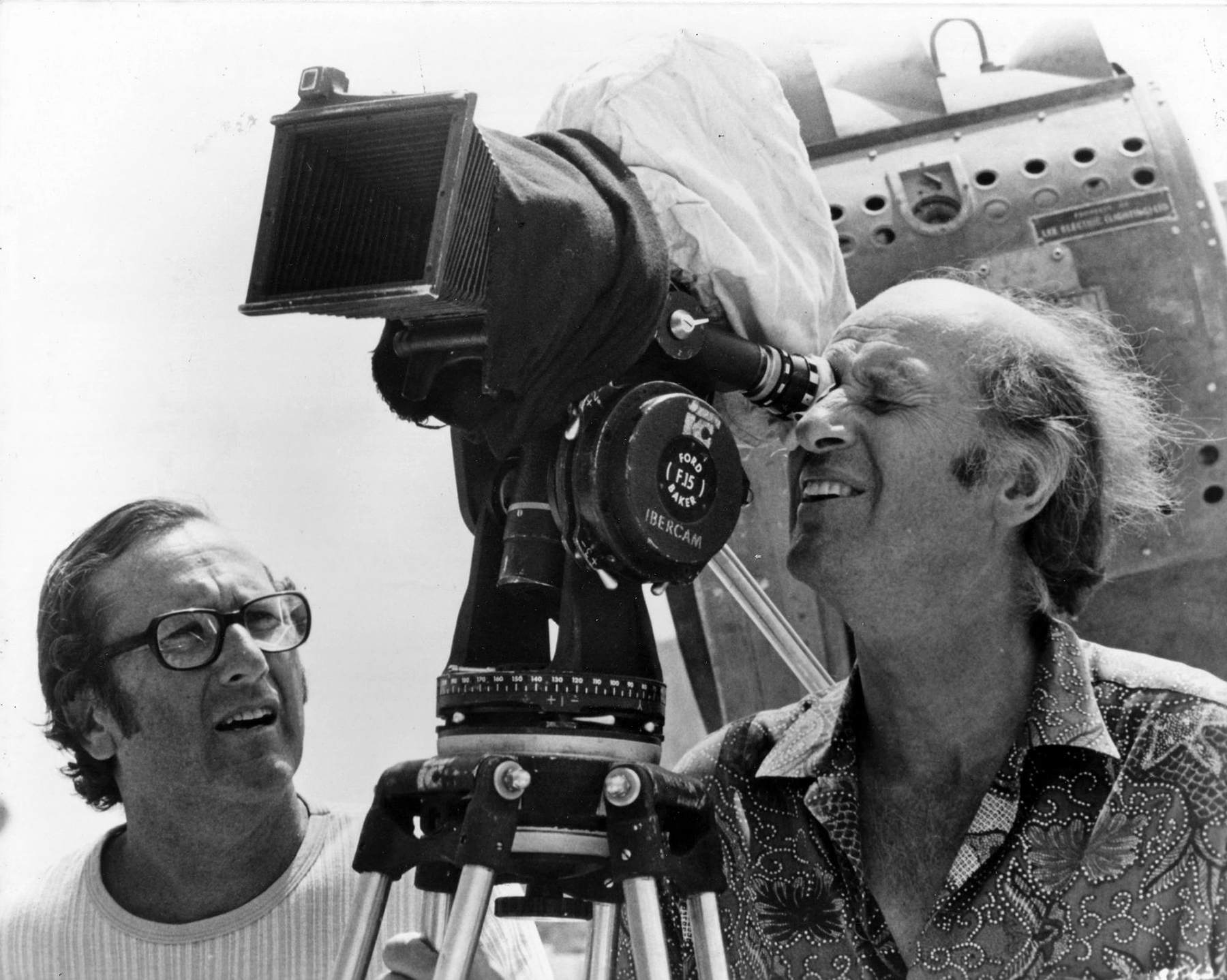

Grand wizard of special visual effects, Ray Harryhausen has just completed his 16th motion picture in a career spanning 41 years. Clash of the Titans is the 12th he has worked on with longtime friend and producer Charles H. Schneer, the eighth to be filmed in Dynamation, a term coined by Schneer to describe the technique of mating live-action and stop-motion animation which Harryhausen has pioneered into high art.

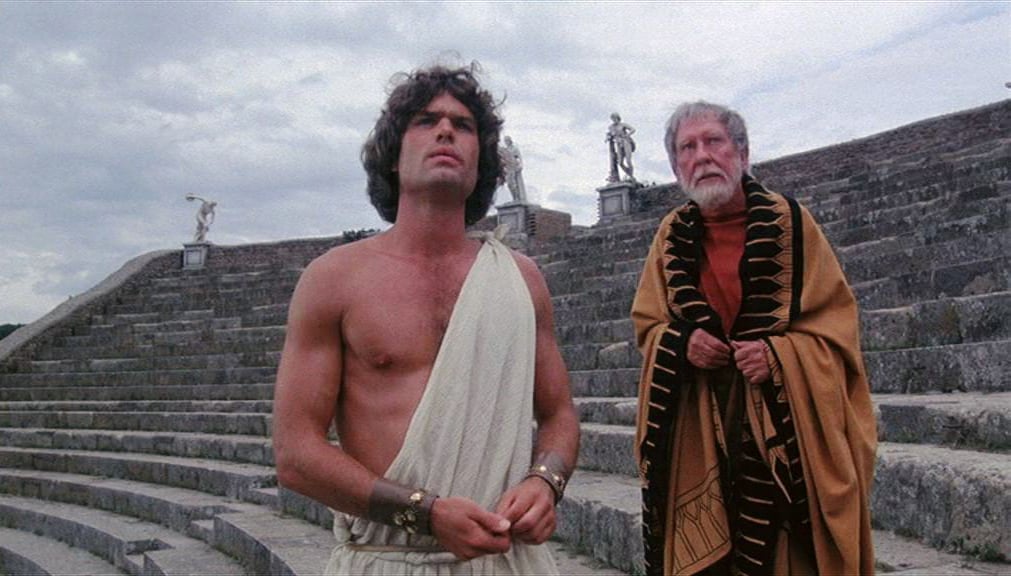

Representing MGM’s most ambitious project in more than 10 years, Clash of the Titans is a fantasy adventure with its roots in mythology. Desmond Davis is the director and “more stars than there are in the heavens” include Harry Hamlin, Judi Bowker, Burgess Meredith, Maggie Smith, Ursula Andress, Claire Bloom, Sian Phillips, Flora Robson and Laurence Olivier as Zeus, Father of the Gods.

To find out about the techniques of filming this epic, American Cinematographer traveled to England where Los Angeles-born Harryhausen has now lived and worked for 21 years.

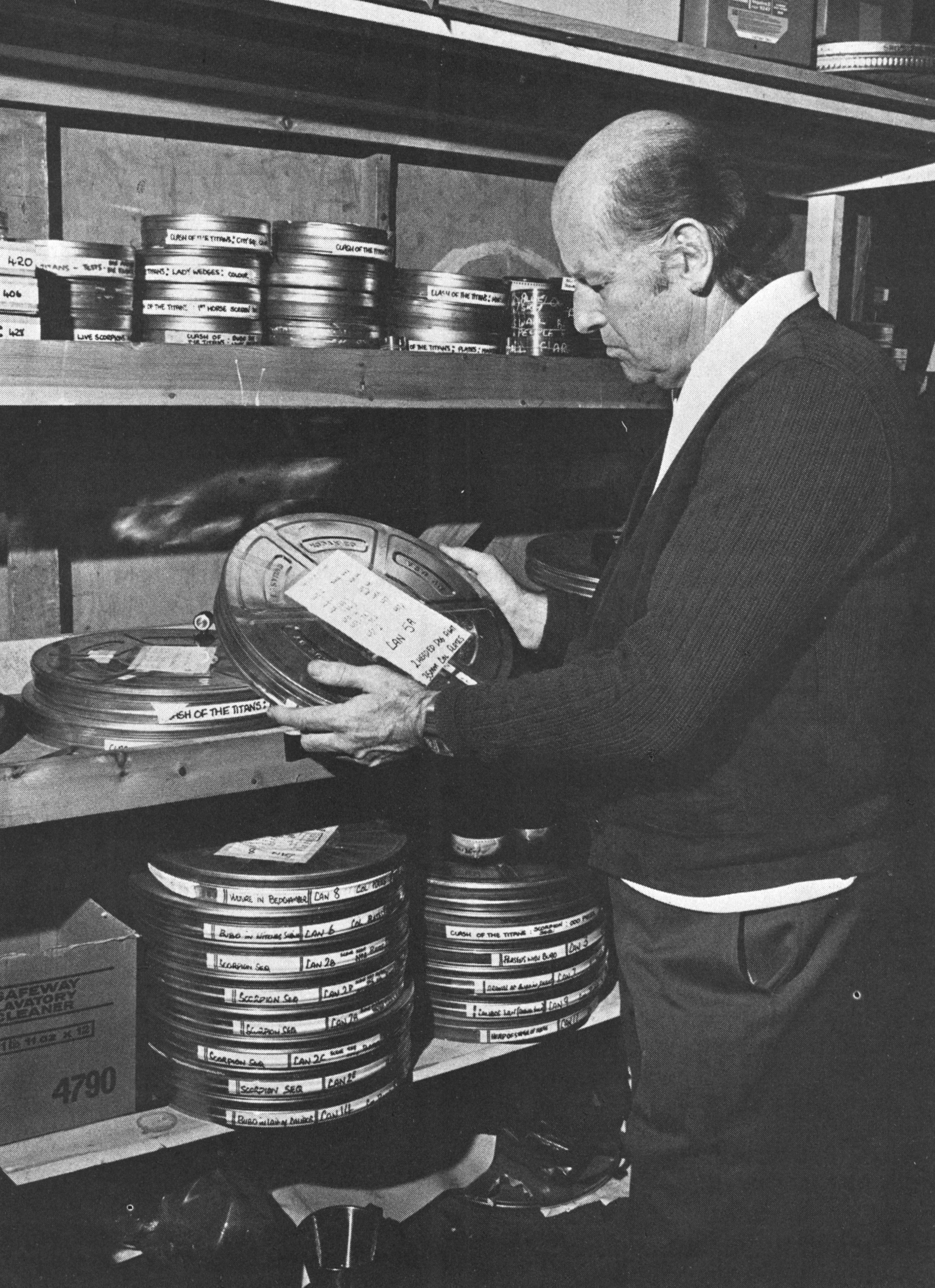

The wonderful world of Ray Harryhausen is entered by a paint-scarred door that creaks open in one of the more remote corners of Pinewood Studios, 15 miles from London. For the past two-and-a-half years the old sound state has been his working home, and the place, quite frankly, is a mess. The Harryhausen technique has always seemed to be one part technology to two parts schoolboy improvisation, imagination without limit, and an infinite capacity for taking pains. All is reflected here.

Creatures — always “creature,” never “monster,” as Harryhausen abhors the word — lay disemboweled on the floor, their ball-and-socket skeletons removed to make newer and better models. An electronically operated owl with a mechanism sophisticated enough to guide a missile leans against a bottle of Fairy Washing Up Liquid — “better than glycerine for highlighting creature features when you go in for the close-up,” claims Harryhausen.

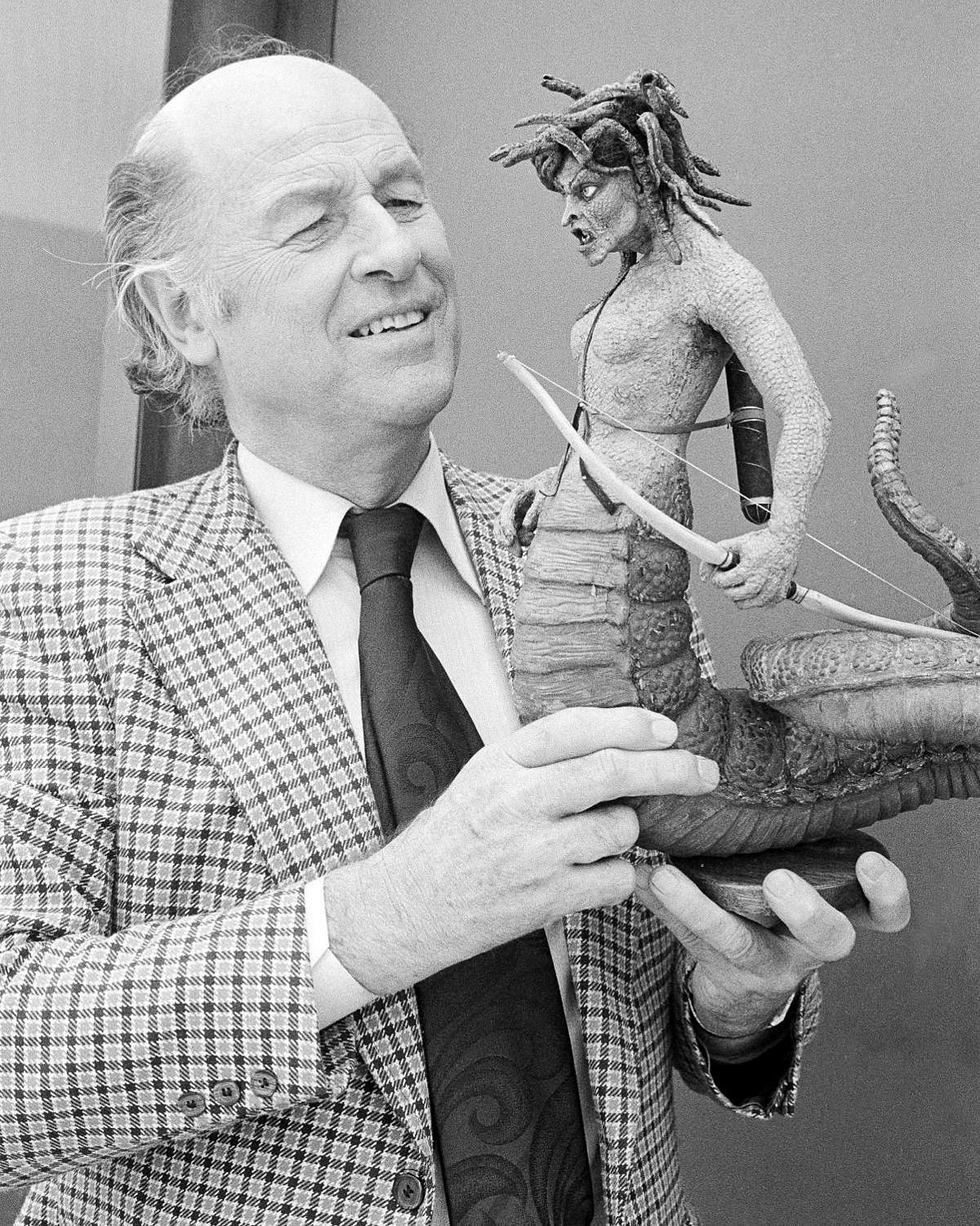

A pair of porcelain eyes awaiting the paintbrush hang from a tripod fashioned from clothes pegs and knitting needles. Soon they will go into the foam rubber head of a Gorgon whose hair has been replaced by 12 snakes, each containing 25 joints.

Comic book clippings and leather-bound art volumes, wheels from construction sets and his own beautiful sculptures all litter the surface of what Harryhausen optimistically calls his worktable.

the camera. He does not use computer animation, feeling that the personal touch of hand animation is needed.

Though he could write the book on the technicalities of his craft, and indeed has contributed to all the definitive treatises on the subject, Harryhausen’s preoccupation remains the story he is helping to tell; a man more interested in beautiful music than in the hi-fi equipment which plays it.

Pressed hard he will cautiously reveal some of the secrets of Dynamation, but his real passion is reserved for the untold adventures he would like to film, the new creatures he would like to create, if only there were just enough time and money left in the world.

One name recurs throughout his conversation, the name that started it all for him: King Kong.

Harryhausen was 13 when he saw the 1933 film at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and became an instant disciple of Kong’s creator, Willis O’Brien.

“I was intrigued by the film because I didn’t know how it was done,” he recalls. “I knew it wasn’t a man in a suit. The film played on my imagination. I had been making dioramas as a hobby out of clay, the La Brea tar pits and various other prehistoric subjects, and I saw in King Kong a way of making these things move.

“I began making my own films in the back garden. We had no lights but a friend had bought an old Victor 16mm camera and offered to shoot footage. We made a bear out of my mother’s fur coat and started animating in the early morning. We finished in the late afternoon by which time the sun had shifted so that as the bear came out of the cave the shadows were moving across the screen. I wanted to do it much better, so got involved with photography and lighting.

“I was then about 15 or 16, and I made it my duty to try and find out how King Kong was made. Occasionally there would be something in magazines describing ball-and-socket joints, etc. I collected every bit of information I could about stop-motion animation and it all developed from there.”

While still at school, Harryhausen studied art direction and photography at a night course run by the University of Southern California under the guidance of various members of the film industry — editors, art directors, and cinematographers such as Lewis Physioc, ASC. After a brief flirtation with acting and a stint at the Los Angeles City College Drama department, Harryhausen returned to sculpting, drawing and planning fantasy films.

In the early 1940s Harryhausen joined George Pal, then producing a series of animated films called Puppetoons. Pal’s puppets were very stylized figures turned on a lathe and cut from plywood. For each move, there was a separate figure and one step could involve 24 figures. Although Harryhausen learned a great deal about photography and gained practical experience, he found Pal’s kind of animation limiting.

He spent World War II making orientation and instructional films for the services and not wanting to go back to limited puppet animation. On his return to civilian life, Harryhausen embarked on his own series of animated fairy-tales. Known as the “Mother Goose Stories” the films still show in schools. Harryhausen’s “studio” was behind his father’s garage and production was a family affair. His mother made the costumes and Harryhausen Sr., a machinist, made the joints and armatures.

Harryhausen was "chief animator" for the Puppetoon short "Tulips Shall Grow" in 1942.

Before Harryhausen went into the Army, he conceived and started work on a film called Evolution. It was an ambitious project tracing the emergence of the world from a swirling gas in space up to the age of the mammal. He had shown his footage to Willis O’Brien and in 1946, when O’Brien was preparing Mighty Joe Young, Harryhausen was hired to work on the film.

He worked with O’Brien and producer Merian Cooper for about three years. The first year he spent cutting frames for drawings, copy-typing, anything to gain experience, and then began to help with the animation of Mighty Joe.

Various projects envisaged by O’Brien and Cooper such as Food of the Gods, Valley of the Mist, and Mighty Joe Young Meets Tarzan failed to get off the ground, and a friend then introduced Harryhausen to Jack Dietz. The producer had an outline called Monster From Beneath the Sea, which became The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and Harryhausen’s first solo feature film.

The film became one of the “sleepers” of the year, but between the end of production and release Harryhausen returned to his fairy tales. Cinemascope and wide-screen gimmicks were then the vogue and Warner Bros., the distributors, worried that as The Beast was not in color it would fail to get theater bookings. They solved this by tinting the film brown and releasing it with the promotional tag “Glorious Sepiatone.”

Friends have played a large part in Harryhausen’s destiny and it was another friend who introduced him to a young producer named Charles H. Schneer. He wanted to make a film starring a giant octopus that pulls down the Golden Gate Bridge. They got together and made It Came From Beneath The Sea.

It was the start of a partnership and friendship which has endured for more than 30 years. In 1959 the pair moved to England. We asked Harryhausen why.

Ray Harryhausen: We had made three or four films in Hollywood and then someone came to us with a script called Gulliver. We wanted to make the picture and the best way to do it was through traveling matte. Hollywood didn’t have extensive facilities at that time to do traveling matte properly, and we’d heard of the sodium vapor process, where you have an instantaneous matte, which simplified the work. We had so many traveling mattes in the picture, we decided to investigate the process, which Rank had developed. We came to England and made two pictures using the sodium backing. Mysterious Island and The Three Worlds of Gulliver.

American Cinematographer: Why was this process only available at Rank’s studio, Pinewood, London? Hollywood at this point was surely in advance with technique.

Hollywood, I think, had too much invested in rear-projection and they felt with triple-head projectors and everything they could achieve what was needed. You occasionally saw a traveling matte shot in a Hollywood film, but it became a forgotten art, although Hollywood had traveling matte when they made films like Noah's Ark making use of the old Dunning process and the Williams process in black-and-white.

When it came to color, they never seemed to develop the art to any great extent because most of the studios had big rear-projection departments with enormous amounts of money invested. They probably didn’t want to change.

Many pictures didn’t call for traveling matte but when you are dealing with big people and little people you have to resort to its use. The Rank T.M. Laboratory, with Vic Margutti in charge, had the [sodium vapor] system that was able to produce a moving matte instantaneously by bi-pack. We felt it would be a great asset to Gulliver. Disney had a franchise on the system in America.

We made the two films and liked it so much in England we stayed. We were also right in the hub of Europe and could get to any exotic location in four or five hours. We felt that Malibu, the Grand Canyon and all the scenery around Hollywood was being rapidly used up by television. Too familiar a background couldn’t possibly be used in a fantasy film. When we did The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad for instance, we wanted some authentic Arabic buildings. The Middle East was in turmoil, so we settled in Spain and used the Alhambra, with its marvelous Moorish architecture.

Some of your equipment is, I think, quite old ...?

Yes, we have a Mitchell NC, I think it was the 15th Mitchell ever made and we still use it. It would stand up to any modern-day camera. They were so well made that if you take any kind of care of them they will last forever.

On Titans we had to use extra cameras. We had three equipped with stop-motion motors and two projectors. In fact, we had three in order to keep a flow of footage coming out to try to keep up with the schedule.

How does a stop-motion camera differ from a regular camera?

Mainly in regard to the motor. A stop-motion camera has a motor that will make a very accurate one-frame exposure and it is very important that this motor be reliable. You are producing a single-frame exposure and if the exposure varies in any way you get a flicker and other problems. We used some of the stop-motion motors that were used on the first King Kong in 1933, but have recently purchased new ones.

Have cameras changed very much over the years?

The basic principle hasn’t changed, although now you can get much smaller compact cameras, and much more reliable motors working on a simpler electronic principle. I still like to go back to the 1933 type of motor, in spite of some of their shortcomings. I find them very reliable.

The action of the film is shot on location or in the studio at a certain lighting exposure determined by the director of photography. What problems do you have in matching the lighting when you place your creatures into the film? Do you make a series of charts relating to the slate numbers, for example?

I try to match the lighting that is on the background plate. It is very easy to see where the key light is coming from and during production, we make very careful diagrams. Of course, there is a big problem with color balance when you try to reproduce a piece of film.

If it is not carefully adjusted, the projection light source sometimes changes the whole tone of the colors. To intercut with the production footage you have to be very careful to try and get as accurate a color rendition as you can. This is accomplished by filters and other techniques to bring the light source into line. We have the assistant cameraman make accurate measurements as to how far the creature is supposed to be from the camera in relation to the people. We also have cardboard cut-outs to portray the creature. If the monster is very large we have someone hold a long pole to give a point of focus for the actors and extras. We’ve had a wonderful series of cameramen on our films. In our first days in England, we had Wilkie Cooper [BSC]. On Clash and our last two pictures, we have had Ted Moore [BSC].

What film stock do you use?

Basically, 5247 [by Kodak]. Film stock today is much more sensitive to the reproduction of an image and new lenses create a much sharper background. We had problems with our first color picture, The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad. It was necessary to use normal print stock for our background plates. We went through months of agony testing various color renditions.

There wasn’t any other stock at that time, but in recent years there have been new developments. Now we use a positive stock from which they make special low-contrast prints for television. It has a lower-contrast ratio and has made color reproduction much easier and much more accurate. When we made The Three Worlds of Gulliver and The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, we had to flash many of our background plates so the blacks wouldn’t go too black when they were rephotographed.

What do you mean by “flash?”

Flash means you have to expose the film before printing and fog it slightly — thus making the blacks go slightly grey. You have to control it very carefully. The film tends to pick up contrast in reproduction. Now you have 5247 and if the plate is shot properly it has a much better reproduction quality.

Do you try to use the same batch of film when you shoot your creatures as that used for the plates?

We try to. We have to have specially perforated stock. Today, because of the laws of economics, stock is produced at such a rate of speed that sometimes the sprocket holes suffer from inaccuracy We have to pick the film very carefully to have as accurate a sprocket hole as possible so that when two or three pieces of film are put together you don’t find them wobbling against one another. It is amazing over the years how this type of problem has increased rather than decreased. It is due to a number of different reasons. We try to get off the first 20,000 or 30,000 feet before the punch starts to produce overly large sprocket holes.

What other problems are there for you that differ from regular film-making?

We have to be very careful about perspective because if you are using miniature projection, it is very difficult to make the insert of the animated figure move toward and away from the camera. Many times you will not use the same lenses as used in the original photography. If an actor starts in the background and moves forward he increases in size very rapidly if a wide-angle lens is used. When you come to insert the animated creature moving in the same direction the fact that you have used a different angle lens necessary for reproducing the background plate causes changes in the whole concept of the perspective of the shot. It has to be very carefully controlled and designed in the way the action is staged. It is necessary to cope with this problem during production rather than afterward. I seldom use a wide-angle lens for rephotography of a rear screen image because of the risk of showing up the “hot-spot” in the middle of the rear screen.

What is a “hot-spot”?

A ‘hot-spot’ means you see the source of your projector light through the image projected on the screen.

Do actors have problems reacting to cardboard cut-outs?

Sometimes. That is why I make a series of drawings of the highlights of the picture, as well as continuity sketches. They show the actor exactly what they are supposed to be looking at in the final scene. For the actor, it is a form of shadowboxing. They are looking and reacting to something that isn’t there. Many times we are able to stage the scene with stand-ins or with stuntmen who will take the place of the creature. We photograph the stuntmen only as a guide to analyze their action. At the same time we make another background plate without the stuntmen, only recording the actor “shadow boxing,”so to speak. This is the actual piece of film we later use to combine the animated model.

What exactly is a “plate”?

I do not know how the term came about but we have always called the piece of positive film used for reproduction, a background “plate.” It consists of a specially printed strip of positive film made from the original photography. It is placed in a rear miniature projector and reproduced with another camera. It is most important that it has negative, Bell & Howell, sprocket holes for accuracy and registration.

Film goes through the camera at a certain speed. In your work do you have problems adjusting to this speed?

The speed of live-action photography is always 24 frames per second and you have to judge the speed of the movement of your animation accordingly. The broader the movement the faster the model will appear to move. It presents a problem of timing because your creatures and actors must appear to be photographed at the same time.

This makes it necessary to sometimes move the figure about one-half of a millimeter per frame in order to keep in synchronization with the live actors. With slower speeds of movement and many models, I sometimes am only able to produce 13 frames a working day. When I was doing the skeleton fight in Jason and the Argonauts I had seven skeletons fighting three men who were live actors. To move seven skeletons, each with five appendages moving at different speeds, meant I worked very slowly indeed. Of course, there are other days when I can average 25 feet of animation.

You had resistance to using color?

Well, yes. In the early days, when Charles and I made 20 Million Miles to Earth, they had just brought out a new black-and-white stock that was marvelous for reproduction. You could reproduce a background plate and intercut it with the original negative and hardly be able to detect the difference. We had just about mastered the problem inherent in black-and-white when Charles wanted to make The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad in color. "We simply cannot make an Arabian Nights picture in black-and-white,” he said. He kept goading me into experimenting with color in spite of its many obvious problems. The first results were not as good a quality as we had hoped for, but it was the right step in a relatively new field.

Color obviously presents more problems?

Color presents many more problems in reproduction because the various colors change when the plate is rephotographed. At that time, greens for example, unless they had a particular intensity, had a tendency to go very grey. We had the same problem with other colors. When you intercut a rephotographed background with the original production material a jacket or turban would turn a completely different hue.

With color do your models have to be built that much better?

Yes indeed. This is particularly true in the photographing of close-ups of a relatively small model. Detail is most important, particularly in skin texture. The use of excessively sharp lenses to get the best out of the background sometimes makes the model far too sharp in relation to the background. It then makes it necessary to diffuse a portion of the picture for the final effect.

Do you always shoot on 35mm film?

Yes. We shoot full-aperture — from sprocket hole to sprocket hole — for the background plates. This is reduced down to normal Academy or to the 1:1.85 aspect ratio, as the case may be. The larger your negative, the sharper the picture you will get in the background.

We have often wanted to experiment with VistaVision background plates. The larger negative reduced to 35mm would give a sharper picture and better reproduction. But with the large number of background plates we usually have in our pictures, it is questionable if the final results would justify the additional costs.

Returning to color, do you share Martin Scorcese’s concern about the rapid fading of color film?

Yes. We made a picture called The Frist Men on the Moon and I had some clippings from the 70mm version. I took them out of my file a couple of months ago and they were all faded. They had been in the dark and were not stored in bad conditions. I was shocked that the colors had faded after less than 12 or 15 years.

A lot of pictures are being made in black-and-white again and, of course, the three-strip Technicolor process where you actually record or transfer your picture onto black-and-white is about the only salvation. You have to go to China now in order to have that done. I understand Technicolor sold most of their equipment to China and they are the only people who use three-strip release prints. I remember, when working with George Pal’s Puppetoons, we were using black-and-white film with a color wheel. Every successive frame was a different color-red, green and blue. Every third frame was printed one over the other and you got the most beautiful color. Of course, black-and-white film doesn’t fade because it has the silver content.

The answer to preserving film seems to be to go back to the three-strip Technicolor process. Now they say silver is so costly that it will price itself out of existence.

Which of all the creatures you have created was the most complicated or difficult? The skeletons in Jason must have presented problems.

Yes. They are the closest to the human being and therefore probably the most subject to criticism in movement. Dinosaurs, for example, no one really knows how a dinosaur moves, so you can take great liberties, but a skeleton has to move in a way you expect a human to move. You have to conceal all the joints to make it appear there is just bone.

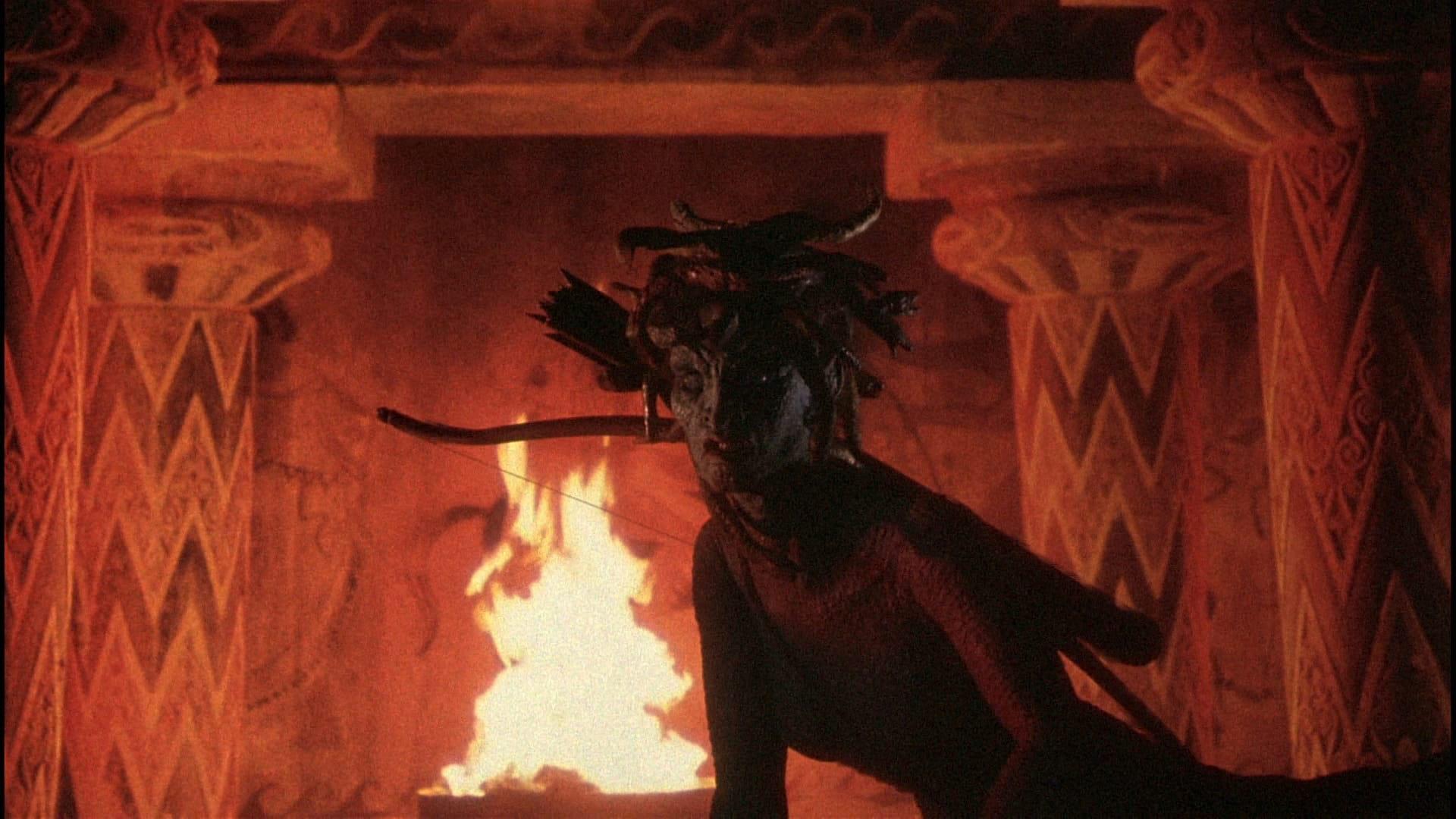

In Clash of the Titans, I think Medusa presented the greatest problem because she had 12 snakes in her hair, and each snake had to be jointed to hold its own position. We could not just stick wires in the snake and expect to get any kind of successful movement. She also had to be a large enough scale to allow a jointed frame in each snake. For every frame of film, I had to move a snake into a different position. She had 12 snakes in her hair, plus the tails, plus her mouth moving, her eyes moved, her fingers moved, she shot an arrow and her tail rattled. She probably had over 100 joints in her body — 150, perhaps — including the snakes.

How were the movements done?

Completely by hand. I do not believe a computer has been devised which could create the complicated movements necessary for our animated creatures to perform. The basic skeletons are made of machined ball-and-socket joints. This enables the model to be posed in any position and hold that position. The big problem is in the synchronizing of all the appendages in order to give the illusion of a living being. Most of this illusion depends on an inward feeling for movement by the animator.

The ball-and-socket joint — is that a new development?

Willis O’Brien devised it in the early days of the making of The Lost World (1923), and even before. The basic ball-and-socket joint is quite an old device, but Willis O’Brien was one of the first to adapt it into the design of humanoid or animaloid miniature figures for stop-motion purposes.

Have there been many recent developments in the creation of movements of the creatures?

In the field of stop-motion, not that many. Of course, the actual design of any creature brings with it its own innovations. There are various devices for aiding in making smoother animation, but the movement itself is still largely locked inside the animator until it is freed by the use of stop-motion photography.

How do your creatures differ from the Muppets, for example?

A Muppet works on an entirely different principle. The Muppet is mainly a hand puppet, sometimes utilizing electronics. They have been able to get some very unusual and interesting characterizations, such as Yoda, in The Empire Strikes Back. Where we have to resort to the long stop-motion process for the creation of the illusion of life, a Muppet can be photographed much like a normal live-action actor.

Are you tempted to use that process?

We have resorted to hand puppets in the early days, such as some shots for The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. But, all in all, we tend not to use the technique, as it is not as suitable for our type of stories.

What about electronics, for instance?

That, again, is a possibility. We have gone partway into electronics with Bubo, the mechanical owl for Clash of the Titans. There are some scenes where he is radio-controlled.

How much of Bubo in the film is radio controlled?

In quite a number of scenes where the actors are handling him. His wings flap, his head will revolve, his eyes spin and his mouth will open. But basically, unless many owls were made to do many different things, his movements are limited. For example, it would be difficult to make an electronic owl walk or take off and fly. For this type of movement and more intricate characterizations, we found it necessary to resort to a stop-motion model.

Do you think the electronic process is limited?

It is limiting because you are resorting to motors to create movement rather than animation where you have great flexibility. It is an entirely different problem when you are shooting a rocket ship and using a computer camera.

What is a computer camera?

A computer camera is a repeat camera which will repeat its exact movements in stop-motion or live-action or slow motion.

Is it like a stop-motion camera?

Yes, it sometimes involves stop-motion. It is controlled electronically so that it can repeat every movement. It has to be on a track, it has to be geared in a certain way and it has to be programmed so that no matter where you move it can repeat that exact position again and again.

Would it not be of any use to you at all?

Not particularly. It certainly would be an asset in certain types of scenes but we haven’t come across those at the moment.

Your work is very personal, very tactile, whereas, using a computer camera is very impersonal. Is this perhaps why you don’t like the electronic process?

It is not a question of whether or not I like the computer camera. It is more a question of whether it can be applied to our type of film. Yes, I do feel there is a personal connection in what I do and the way that the final effect is achieved. Stop-motion animation is a personal expression of the animator needing complex movements along with ad-lib character details. There is a big difference between photographing an inanimate rocket ship flying through space and the complex movements of, say, the Jason skeleton fight. Each has its place in the type of story being told.

In Clash of the Titans was there any creature you wanted to use, but couldn’t because of budget restrictions?

No, we used everything we set out to do.

Do you have a vast storehouse of fantastic creatures lurking in your mind waiting for the chance to emerge?

The creatures sort of develop from the story, but I probably do have a number of things in my subconscious which will not come out until the right script is presented. In Clash, which deals with Greek mythology, I tried to go back into the past to see what other artists had done. We found, for example, that Medusa has an enormous number of variations. In some pictures she is a beautiful woman with snakes in her hair, in others she is just an ugly sort of middle-class housewife. But for our situation, we felt Medusa should have a snake’s body. We wanted her face to have a beautiful bone structure but with an ugly overtone because I cannot imagine a beautiful woman turning anybody into stone — even if she does have snakes in her hair. Or, perhaps the more subtle implications have escaped me. We tried to make Medusa more grotesque so that there was the possibility her looks could be frightening enough to turn someone into stone.

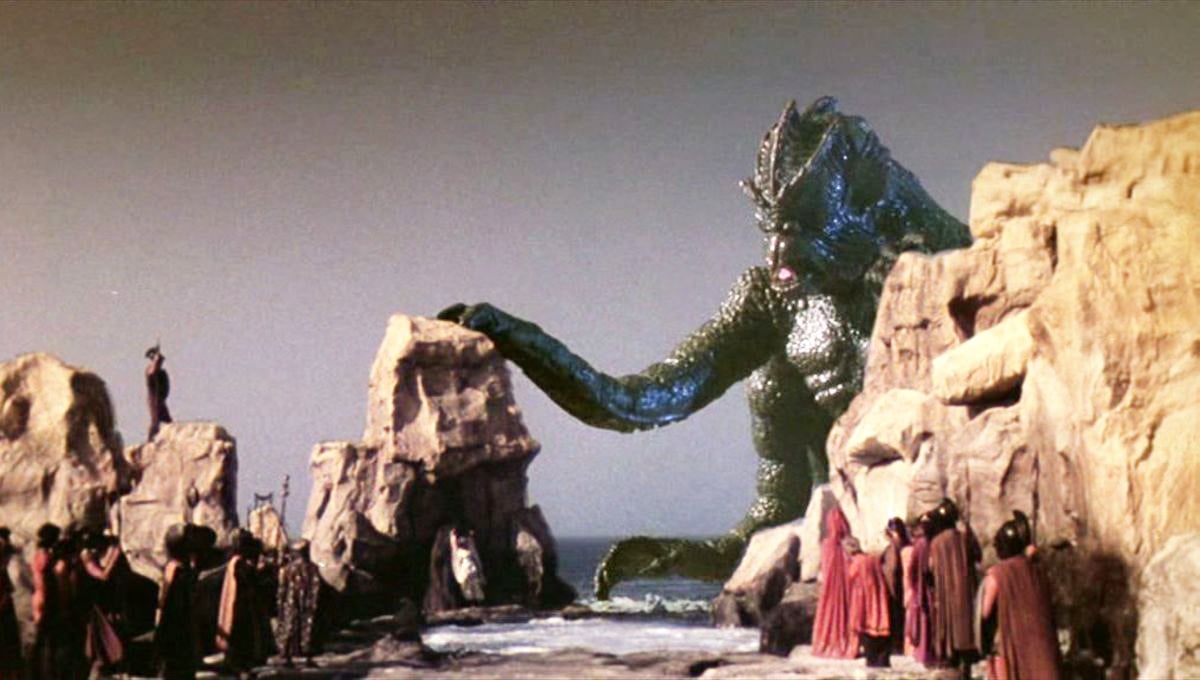

What about the Kraken? He doesn’t really exist in mythology. Is he your creature totally?

Only in the design. In the script we called him the Kraken, although the word comes from a much later period in history when medieval sailors returned with tales of giant squid and whales, etc. There was a leviathan in early Greek and biblical times, of course, and various other names for grotesque sea monsters. Andromeda was sacrificed to a sea monster of some sort and there are various paintings of what he looked like. Sometimes it’s a dragon, sometimes an enormous fish but I’ve never seen it as an octopus. We tried to make it a combination. We wanted it slightly humanoid to give a reason for her being sacrificed to this thing, otherwise, the creature would just devour her and go back to the sea — not a very dramatic situation.

Is it scarier if the creature has certain human qualities?

Yes, that is what we had in mind. We gave it four arms with the basic form of a combination of sea creatures. There is sort of a merman concept combined with octopus overtones. We gave it four arms rather than eight because we thought that would give a more grotesque and unusual appearance. This was not because we had budget problems as we did on the film It Came From Beneath the Sea where we had to compromise with a six-armed octopus to pull down the Golden Gate Bridge.

There were problems with the Kraken though. We seem to remember a large Kraken flopping around in the sea off Malta?

Yes. I really dislike men dressed in dinosaur suits almost as much as I dislike seeing a man in a Kraken suit. Sometimes one is forced into using them by circumstances and time. In the end, we used only the Dynamation shots. However, we did build a large Kraken for the underwater scenes. Under the photographic supervision of underwater cameraman Egil Woxholt, we built a submerged set in Camino Bay, off the island of Malta. We had to tow a 15-foot model in and out of the underwater cage. As you can imagine, there were many problems in working beneath the sea, as well as working with such a large model. One major drawback was that the wretched monster always wanted to float. He was made of a sponge substance. Many hundreds of pounds of lead had to be used as ballast. Unfortunately, when we left the location overnight all the lead was pilfered and we had to start from scratch the next morning.

How about the scorpions?

They were another type of problem. They had eight legs and two claws and a tail, all of which had to be kept in motion. We had to make them on a much larger scale than a live scorpion. The trouble with live scorpions, even if you found a talented one, is that they are difficult to train and make do exactly what the script requires.

And Dioskilos, the two-headed wolf dog?

One of the big problems in designing Dioskilos was that once you start branching two heads out of a normal dog’s body it becomes grotesque. We had to manipulate the design quite extensively to get it to look believable, but he comes out quite well.

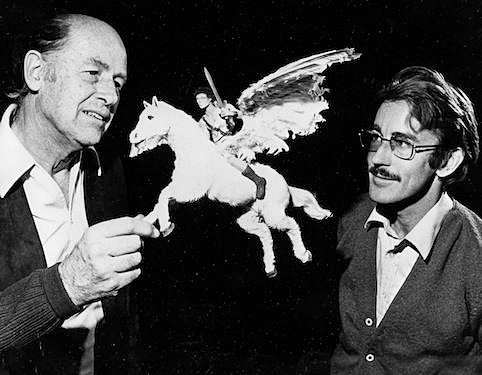

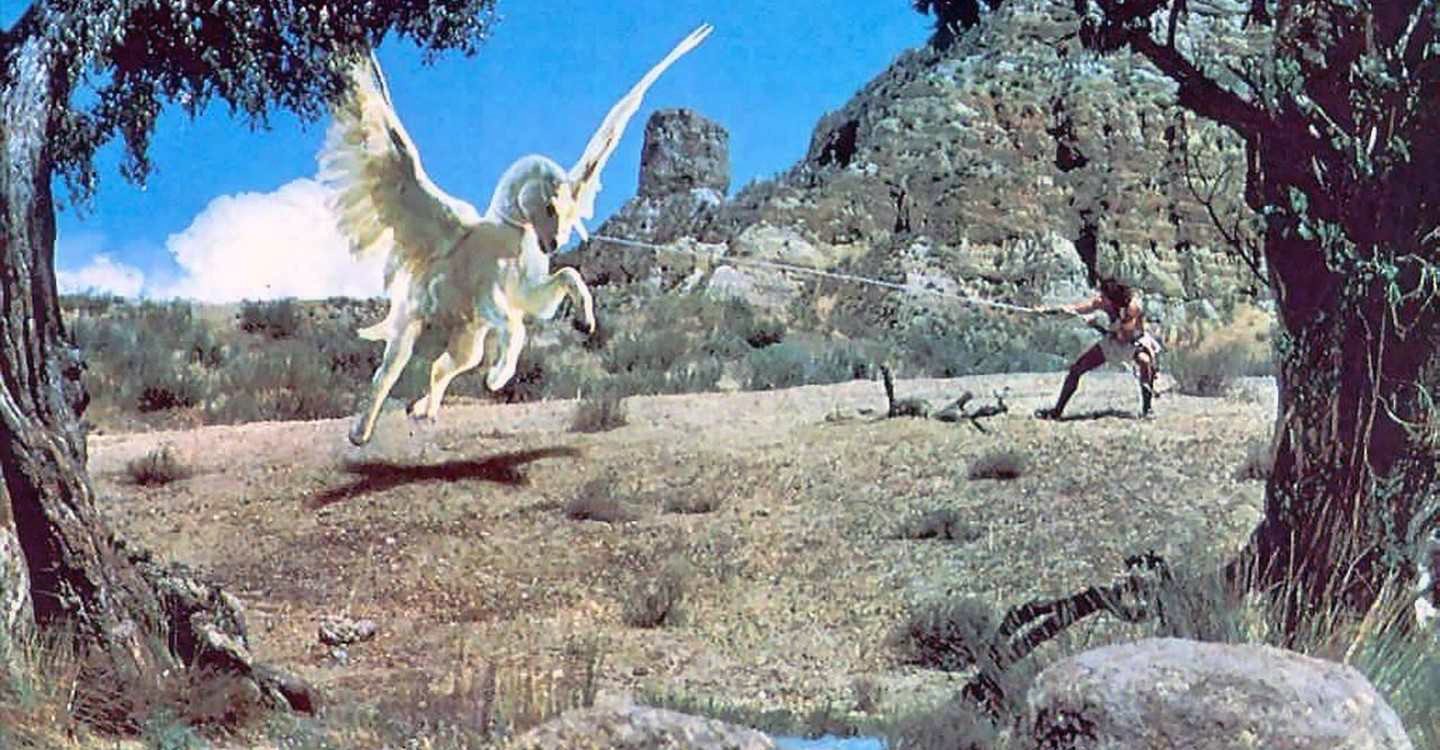

Pegasus the flying horse is part real, part animation?

Yes, because of the detail in a horse’s head we used a live horse in certain shots, but the long shots are all animation.

How big are the models you use?

Some of them are very small. I once made a model of Raquel Welch only 3 ½ inches high. In the film One Million Years B.C., she had to be picked up by a giant pterodactyl. I did not want to make an enormous life-size winged lizard, so I made a small Raquel Welch and animated her frame by frame. Of course, other models can be much larger, as much as two-and-a-half feet in height.

What dictates size?

It depends on what the creature has to do. Many times a smaller model is easier to work with. I almost feel like Dr. Frankenstein or Dr. Cyclops in that respect because I take actors and shrink them down in order to make a model look large rather than build a big model which is uncontrollable.

Before filming begins you lay out the whole film in storyboard form. Why?

Because in photographing anything there is an expensive way to do it and an inexpensive way. Sometimes, just setting the camera three feet lower or three feet to the right or left can make the difference when you are animating the final scene. It’s the difference between spending one day or 10 animating, because of the complications a particular camera angle presents. I find it is very important to layout all the major sequences in rough diagram form in order to have one harmonious point of view with all concerned. It aids the actors to visualize as well as the director and photographer. We go over the complete sequence before production to see if the director has any changes he feels will make the scene better. Of course, there are always compromises one has to make, changes in the weather, charter planes to catch, etc.

Do you care about the actors or are your creatures more important?

Basically, I’m interested in the overall product. As a producer on this film, I take more of an interest than just my part. I want to see a rounded picture that will produce the best results but naturally, I’m prejudiced towards the creatures because we feel they are the unusual values of the production.

With Titans you have an expensive group of actors. Do you have a sneaking resentment that a lot of money was going to them rather than your creatures?

I cannot deny the thought had passed through my mind. In the past, we have found the story we were telling did not command a very expensive performer, but in Titans, we felt it would enhance the end product by having as good actors as we could possibly get.

Why have you never directed an entire picture yourself?

The problem is that a film of this nature has so many complications, I feel it would tear you apart to try and do everything; something must suffer. I’ve never been that intrigued with directing live-action.

Is there ever conflict between you and the director?

There is always a clash of personality possible, and sometimes that happens. You have to cope with it as best you can. Everyone doesn’t see a certain scene or situation in the same light. I may see a scene developed in a certain way because of my previous experience and the director will have other ideas. This is why, before we get into production, we have to agree on the way a scene should be handled. But, sometimes, out of battle comes a better product, other times it simply hinders. It was once said, ‘When two people think exactly alike, one of them is unnecessary.’

The story ideas, are they yours?

Not always. Beverley Cross for example, came up with Clash of the Titans. I had always wanted to do this story but couldn’t quite figure out a way to solve some of the plot problems. I have contributed stories in the past and then someone like Beverley or Jan Read or various writers elaborate and develops them into screenplays.

Mythology seems to be your main story source.

Yes, I find mythology has a built-in structure for the creatures that we can best do with Dynamation. You don’t have to write the monster into the story. With many stories, you find the elements have to be incorporated just to create the spectacle. I remember in my youth seeing some of the early Sinbad pictures where they just talked about the fantasy element but never showed it. Consequently, the films became simply cops and robbers in Arabic costumes. You never saw any form of magic or wonder. Of course when I viewed Korda’s The Thief of Bagdad that stimulated me even more into believing it was a great truth that you must show the fantasy on the screen the way it is in storybooks and not just talk about it.

Space stories occupy a lot of screen time now. Do they not interest you?

I find them terribly cold and indifferent. The stories are always to do with gadgets and machines and occasionally there is a bit of dramatic personal involvement. I prefer the past; it has a much more romantic quality, much more story value. Somehow, space pictures all end up very similar. If we found a good script, however, I would be delighted to try one. We did H.G. Wells’ The First Men on the Moon, but I guess you would call that a Victorian space epic. It was a lot of fun, but again we went back into the past, to 1900, for the bulk of the picture. We had only the present-day rocket ships to contend with in the prologue and epilogue.

What have been the major influences on your work?

There have been many influences when I look back. Charles R. Knight, who was a museum illustrator and fine painter. He restored concepts of prehistoric animals for the New York Museum of Natural History. As a small child, I would sit for hours looking at his dinosaur books. Willis O’Brien’s The Lost World impressed me enormously at the age of four. The dinosaur falling off the cliff into the mud below became a lasting memory. King Kong and its assorted cast of dinosaurs became a stimulus that changed my life completely. The fantasy film to end all fantasy films. Through O’Brien, I was introduced to the wonderful engravings of Gustave Dore and John Martin. The films of Merian C. Cooper, James Whale, Tod Browning, Rouben Mamoulian, Fritz Lang all expanded my imagination. The list could go on.

Have you not wanted to make a film based entirely on animated creatures with no human beings?

Not really. I like to think my interests have a broader expanse than just creature films. I doubt very much if an audience could sit through two hours of just animated characters. In the early days I made 10-minute animated Fairy Tales on 16mm film simply to gain experience. Subjects such as Hansel and Gretel, King Midas, Rapunzel, and others. I still love to watch a good musical, any good drama, some horror films. Laurel and Hardy make me laugh uncontrollably. There will never be another pair like them.

Now you have become a cult figure, almost the father of stop-motion, what do you see as your position in the business at this time?

I really have no idea. If I stopped to think about it I doubt if I would be able to do anything more in the field of dimensional animation. However, I do feel there is a point in time coming up when we will not be able to function in the same way as we have in the past. Stop-motion, dimensional animation is mainly hand-work. It is personal to me and has been all of my career. Charles and I are most grateful to receive many letters from young people telling us that our films have inspired them toward a new career. Because of television, there are many more opportunities for expansion of this field.

If you had stayed in Hollywood instead of moving to England do you think your work would have gone in a different direction?

I would have to be a prophet to answer that. I have no idea. I just felt Hollywood was not the place for me. We made many films and had marvelous working conditions, but for our type of fantasy film, we felt it would not serve our best purpose.

Is there a film you really want to do? We seem to recall you mentioning Dante’s Inferno.

Dante’s Inferno, as such would make a rather tedious feature, I think, but certain elements of it could be incorporated in the right script. It would be an enormous project and I do remember saying I would like to see thousands of tormented souls rolling up through the heavens in the spirit of Gustave Dore. Unfortunately, the complete story of Dante may not be commercially viable.”

So what are you going to do next?

I have no idea. As we say in Titans, ‘It’s is in the lap of the Gods’

In 1992, Harryhausen was presented with an Academy Award for his lifetime achievements in film. Despite his body of work, he had never previously been nominated:

In 2003, the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce presented Harryhausen with a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, located across the street from Grauman’s Chinese Theater, where he first saw King Kong as a 13-year-old boy. In his acceptance speech, Harryhausen pointed and said, “Everything for me started at that theater 70 years ago.”

The short documentary below from the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art offers additional insight on Harryhausen and his lasting contributions to cinema. Much more can be learned from the Ray & Diana Harryhausen Foundation, the non-profit that chronicles the artist's creativity, life and career.