Real-Time Ray Tracing for Virtual Production

“Project Arena was an opportunity to take things to the next level inside the volume.”

All images courtesy of Chaos

One of the most important aspects of in-camera visual effects (ICVFX) is the real-time rendering engine. This piece of software renders virtual environments on the fly so they can be captured in camera, and it must realistically perform at 24 fps or faster. It also needs to respond to tracking data about the camera’s position to generate realistic parallax.

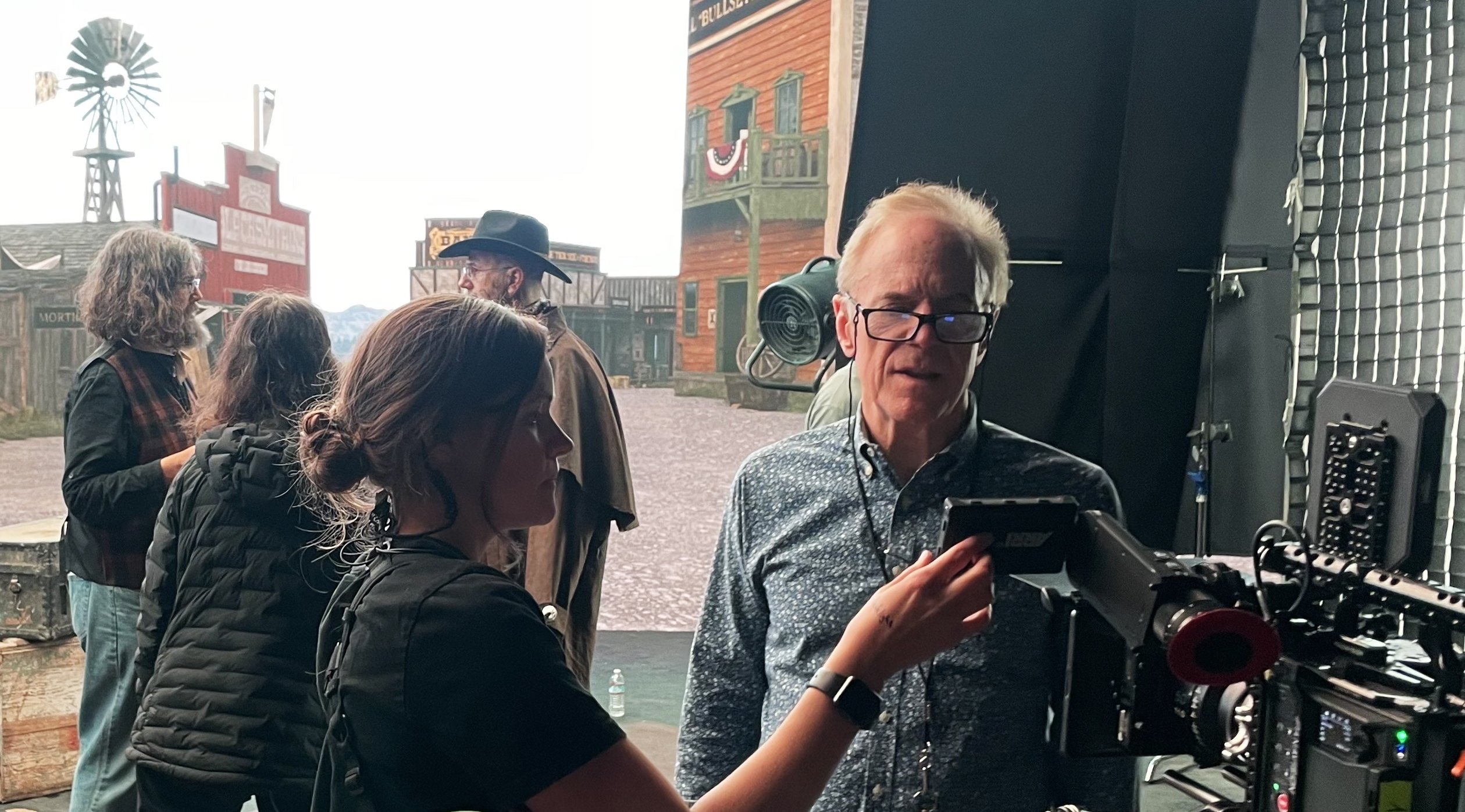

Richard Crudo, ASC recently collaborated with a cross-section of visual-effects artists and software developers to create a short film called Ray Tracing FTW as a demonstration of Project Arena, a new real-time renderer from 3D-visualization company Chaos. (“FTW” is internet slang for “for the win.”) Project Arena uses Chaos Vantage for rendering, which is a real-time version of V-Ray, a ray-tracing renderer that is widely used in postproduction animation and visual effects. While ray tracing is a decades-old standard for CG rendering, it’s only recently that technology has advanced to the point that it can operate in real time on a “monitor” as large as an LED wall.

The focus of Ray Tracing FTW was to shoot an ICVFX production exclusively using ray-tracing technology without the need to decrease frame rate or otherwise down-rez the image on the wall to avoid overloading the processors.

The short is a sendup of classic Westerns. A Who’s Who of visual-effects experts portray movie archetypes, making meta-commentary about the history of their craft. Some of these VFX heads served other key positions on the project as well, including director Daniel Thron; executive producer Vladimir Koylazov; producer and VFX supervisor Christopher Nichols; and writers Thron, Nichols and Erick Schiele.

“Prior to this,” Crudo says, “my experience in virtual production was limited to LED walls for video plates and driving shots. That was an improvement over greenscreen because it allowed you to balance color and exposure without having to rely on visual effects that were completed later. Project Arena was an opportunity to take things to the next level inside the volume. I learned a lot in the process and felt like I was at the very tip of this technology.”

Transfer of Power

Ray tracing mimics how light interacts with surfaces, producing ultra-realistic effects like reflections, refractions and shadows. This contrasts with a technique called rasterization, which was long the primary foundation of rendering engines, and which prioritizes speed by approximating lighting. Although rasterization excels at real-time performance, it can’t achieve the same level of realism as ray tracing, especially with complex lighting and reflections. It’s therefore not surprising that real-time ray tracing for ICVFX has come to the fore — another case in point being Unreal’s development of Lumen.

The challenge in achieving high-resolution ray tracing in real time has been that a single fixture can have millions of rays of light that are traced with reflections and refractions on multiple surfaces — equaling hundreds of millions of calculations per light. Therefore, ray tracing an environment with hundreds of sources — and thus billions of reflections and rays — causes processors to overload unless frame rate is brought down and/or the image is down-rezzed in some way.

Nichols — the director of special projects at Chaos Labs, who has spearheaded Project Arena — explains, “I’ve always been fascinated by ray tracing, which is a much closer approximation to how light behaves in the real world than most renderers produce — that’s what Chaos’ V-Ray renderer does — but it’s so computationally expensive that it’s complicated to achieve in real time. Then, in 2023, Nvidia came up with a new type of AI de-noising for ray tracing, which suddenly enabled the speed of what we were doing to go to a completely new level. That led us to explore real-time ray tracing on an LED wall.”

Project Arena leverages this new real-time ray-tracing capability “using a machine-learned algorithm and Nvidia’s Deep Learning Super Sampling (DLSS) algorithm version 3.5,” notes James Blevins, who served as a virtual-production producer (and actor) on the film. With this system in place, high-resolution, ray-traced virtual environments within an LED volume can be displayed at 24 fps and above, while reacting dynamically without performance issues stemming from large numbers of light sources “or the complexity of the 3D scene,” Nichols confirms.

“There was a moment during testing with Richard when we were moving lights around within the virtual environment very quickly,” Thron recalls. “Until this version of the technology, that’s something you couldn’t do without going back and re-baking your environment, which causes a big delay. Even in the real world, a lighting change on set can take up to 30 minutes. But with this solution, Richard could call for a lighting change in the background and it would happen instantaneously.”

Crudo adds, “As a bonus, you can now isolate things in the volume. One of our shots featured an architectural column within the image on the LED wall. It was highly overexposed relative to everything else, which was relatively mid-range or lower key. When I pointed it out to [Chaos co-founder and executive producer on the film] Vlado Koylazov, he instantly dialed it down. The details then came back in the column, which matched the rest of the shot. That was quite an eye-opener.”

Nichols notes another Project Arena element that veers from the norm: “While we still use frustum rendering to produce cam-era parallax for the in-frame material, we render the entire image at once, rather than compositing the background and the frustum separately, such that the material outside the frustum appears in the same high resolution as the imagery within it. Rendering in a single pass ensures that the imagery within the frustum is always at a perfect resolution, regardless of its size, without stretching pixels. It’s a fully ray-traced image across the entire scene, which sets us apart from how others typically approach this.”

Thinking Like an Artist

Crudo and the team had three days to capture a 10-minute period Western full of characters and action sequences, including a train chase. “My big trepidation was how efficiently the volume was going to operate,” he recalls. “I knew our foreground elements were easily controllable, but could the volume deliver? In the end, there wasn’t one glitch. It was quite something.”

Thron also came away enthusiastic about the process and its potential to offer a better pipeline for directors than traditional postproduction VFX. “When you defer creative decisions to post, it obstructs production because you don’t know what you’re ultimately getting,” he says. “Instead of thinking like an artist, you start to think like someone just gathering data for a pipeline. With virtual production, Richard can line up a shot, and I can look through the lens and see something I didn’t even realize we could grab. You get the images you dream of getting instead of waiting to see what happens in post.”

Reusable Assets

Another notable element of Project Arena is that it features a simple process for using assets created with traditional 3D applications. This means that imagery crafted with an application such as Maya or 3ds Max “can be sent to Project Arena for virtual production and continue to be used in that initial application for postproduction,” Nichols says. “You would use the same asset for both.

“In post, we were looking at a whole sequence that takes place onboard a train, and the environment that was displayed on the LED wall for the scene was the same asset as the one we were using for additional postproduction visual effects,” Nichols continues. “That means the artist creating the new shots in post has the same lighting and assets as the original production. There’s no question about how things should look, because the models are identical and we know things will match. It simplifies the entire process, and it looks great.”

Parting Shots

With the release of Ray Tracing FTW — which can be viewed on YouTube — Crudo had an opportunity to reflect on the cinematographer’s role in virtual production. “The essence of what the cinematographer has to do hasn’t changed at all — you still have to light convincingly and according to the mood you’re trying to create. The primary concern is color management be-tween the wall, the camera sensor, the monitor and the post house. All that requires much attention, testing and weeding out during prep.

“Once you wrangle all of those elements and teams onto the same page, you’re pretty much free to do almost anything you want. When everything is set up well, it’s an absolute dream and easy to work with. Virtual production is not something that any cinematographer should be intimidated by.”

Nichols adds, “The concept of the ‘digital twin’ has been used a lot in the CG and tech world, and in this case, we’re creating a digital twin of a motion-picture camera. Ray tracing sees light the same way a camera does. Project Arena could be anything that has a digital twin; it’s not just limited to LED volumes. If you’re making an all-CG movie, you could also get a virtual camera that behaves exactly like a real camera.”

Below is the completed Ray Tracing FTW demo video from Chaos: