Flight Risk: Up in the Virtual Air

“We never wanted the audience to feel like they were watching something fake or overly produced. We wanted to ground it in reality,” says cinematographer Johnny Derango.

This article was originally published in the March 2025 issue of AC.

The thriller Flight Risk unfolds almost entirely within a nine-seat Cessna 208 as it flies 14,000' above snowy Alaska. Cinematographer Johnny Derango shot the film for director Mel Gibson, working closely with on-set visual-effects supervisor Michael Ralla. “Mel sent me a different script during the pandemic with a big nighttime car chase through the desert,” Derango recalls, “so I began researching virtual production, and in doing so, we visited several different facilities to learn more about the process. Then Flight Risk came about, and we both immediately realized virtual production would be a perfect fit.”

Except for a handful of scenes set on the ground, the filmmakers shot Flight Risk over 22 days of volume work. “Creatively, the reason we went with a virtual-production approach is that Mel and I wanted to sell the authenticity of being in a small plane,” Derango says. “We never wanted the audience to feel like they were watching something fake or overly produced. We wanted to ground it in reality.”

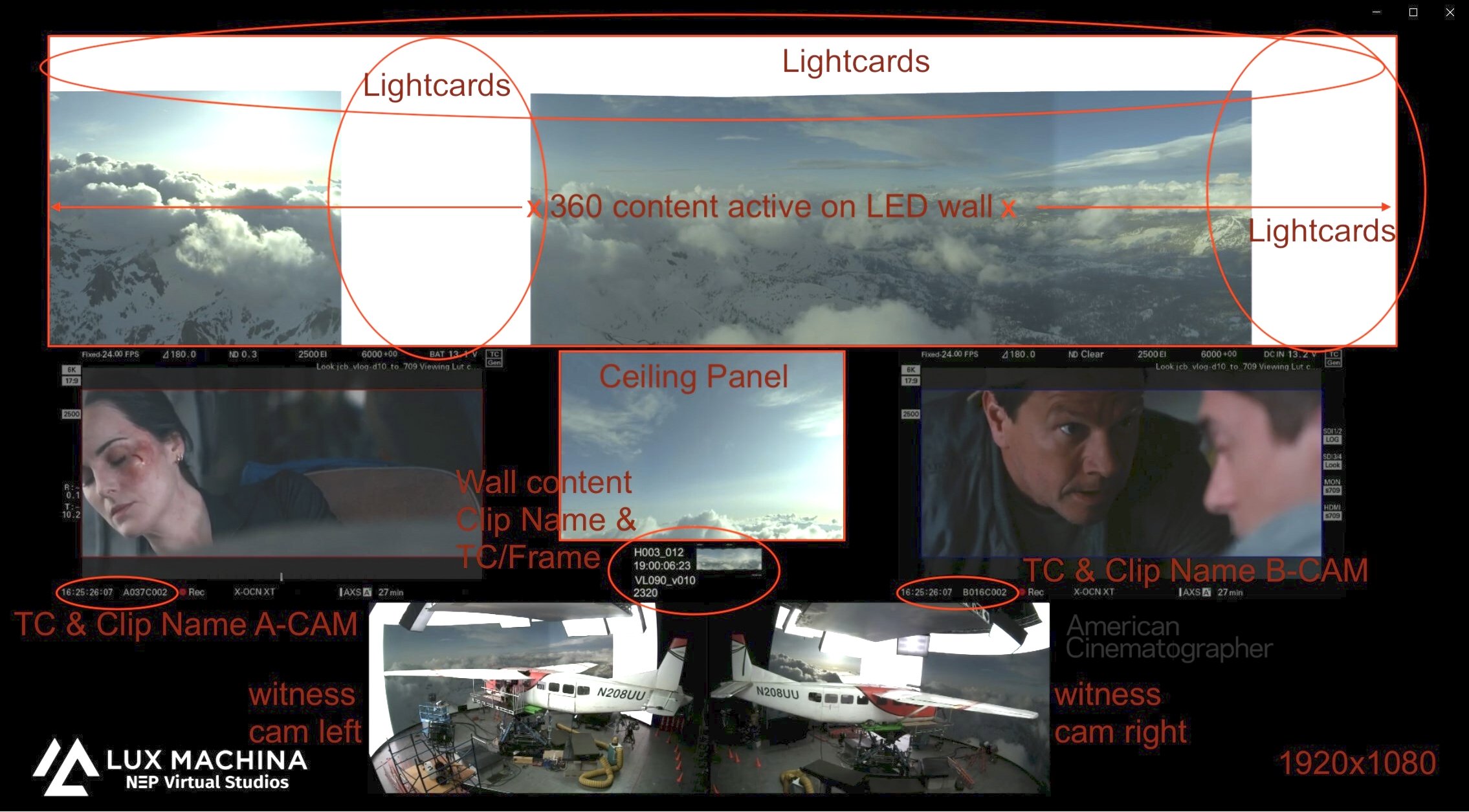

XR Studios supplied the panels for the production, Monolith handled the systems integration, Lux Machina ran the day-to-day volume operations, and the feature was shot on a bespoke stage in Las Vegas.

The cinematographer chose the Sony Venice and Venice Rialto paired with Panavision VA spherical primes for the volume work — and the Venice 2 for night work on the runway, as the plane approaches, and for single-cam work from a helicopter.

Loading the Plates

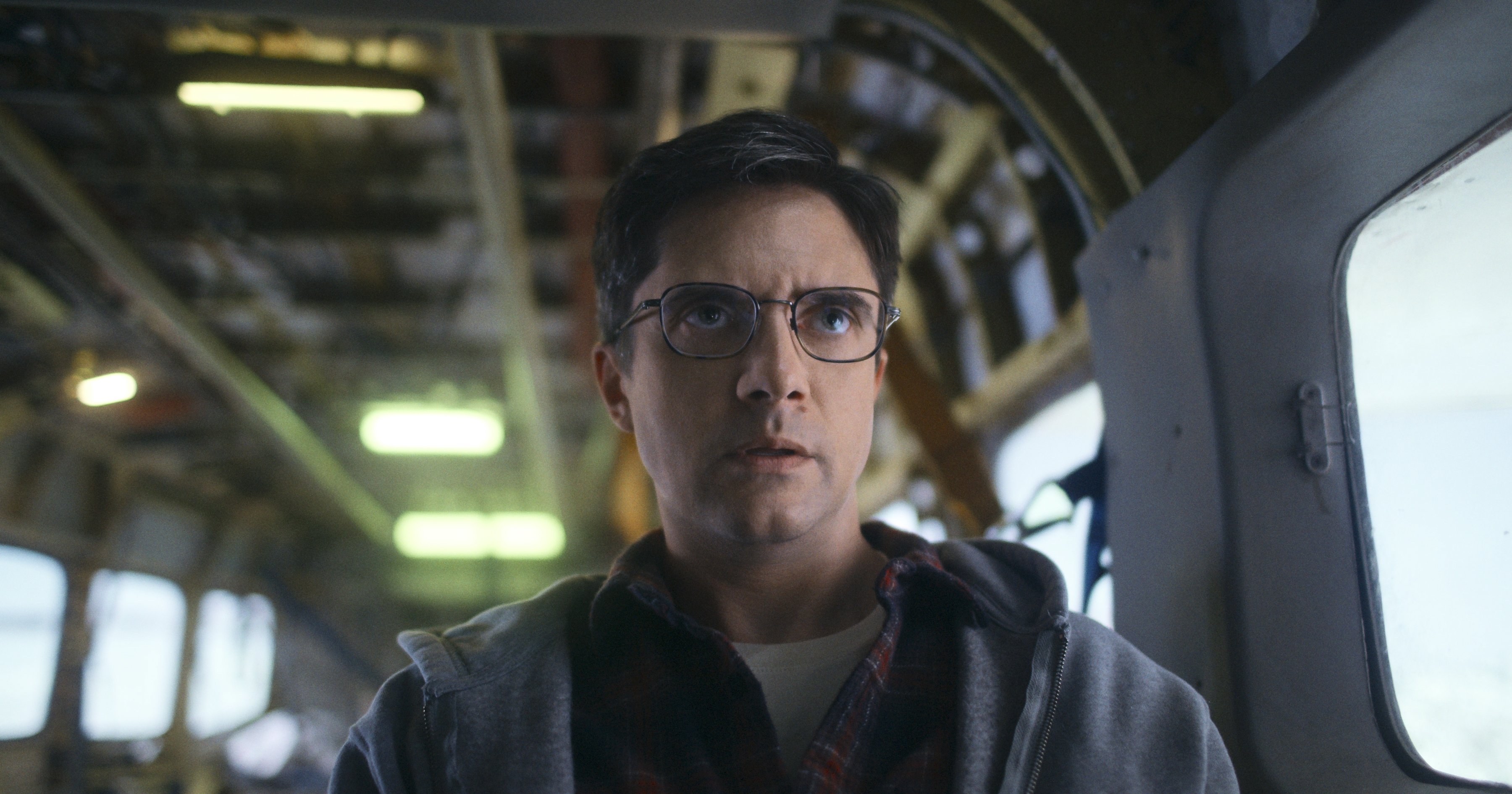

The film stars Mark Wahlberg as a pilot who flies a U.S. Air Marshal (Michelle Dockery) and key witness (Topher Grace) to a trial, and nothing goes as planned. Derango understood that the quality — and believability — of the final imagery would depend highly on the background plates that would be featured in almost every shot.

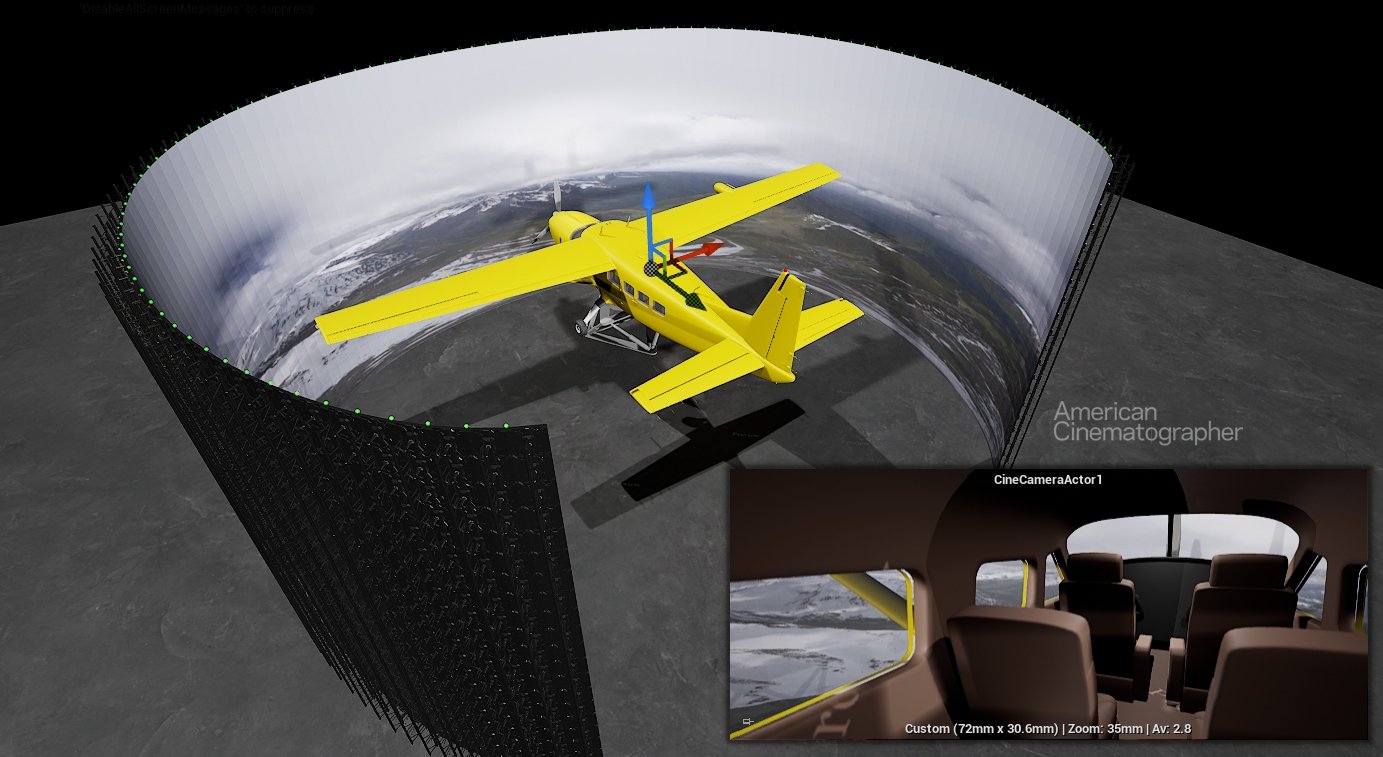

With just eight weeks of prep, he prioritized testing how to best capture the content for the volume with Ralla. “An LED-volume project rises or falls with the quality of the displayed content,” Ralla says. “I did some idealized projection tests in [Foundry’s] Nuke using a 3D model of the volume build to figure out what pixel raster would give us maximum visual clarity on the wall, and ultimately, in the Venice camera, without factoring in lenses at that point — which were a separate testing subject. I calculated that we needed at least 18K horizontally, ideally more, to get sufficient perceived visual ‘resolution.’”

He adds that the Cessna 208 Grand Caravan has large panoramic windows, and the team realized that “to give the camera enough freedom of movement — even if somewhat restricted to mostly rotation and less translation — that not only would the volume build have to be extremely tall, but the content also had to be shot with a high vertical angle of view, which severely limited available 360-degree array-camera options.”

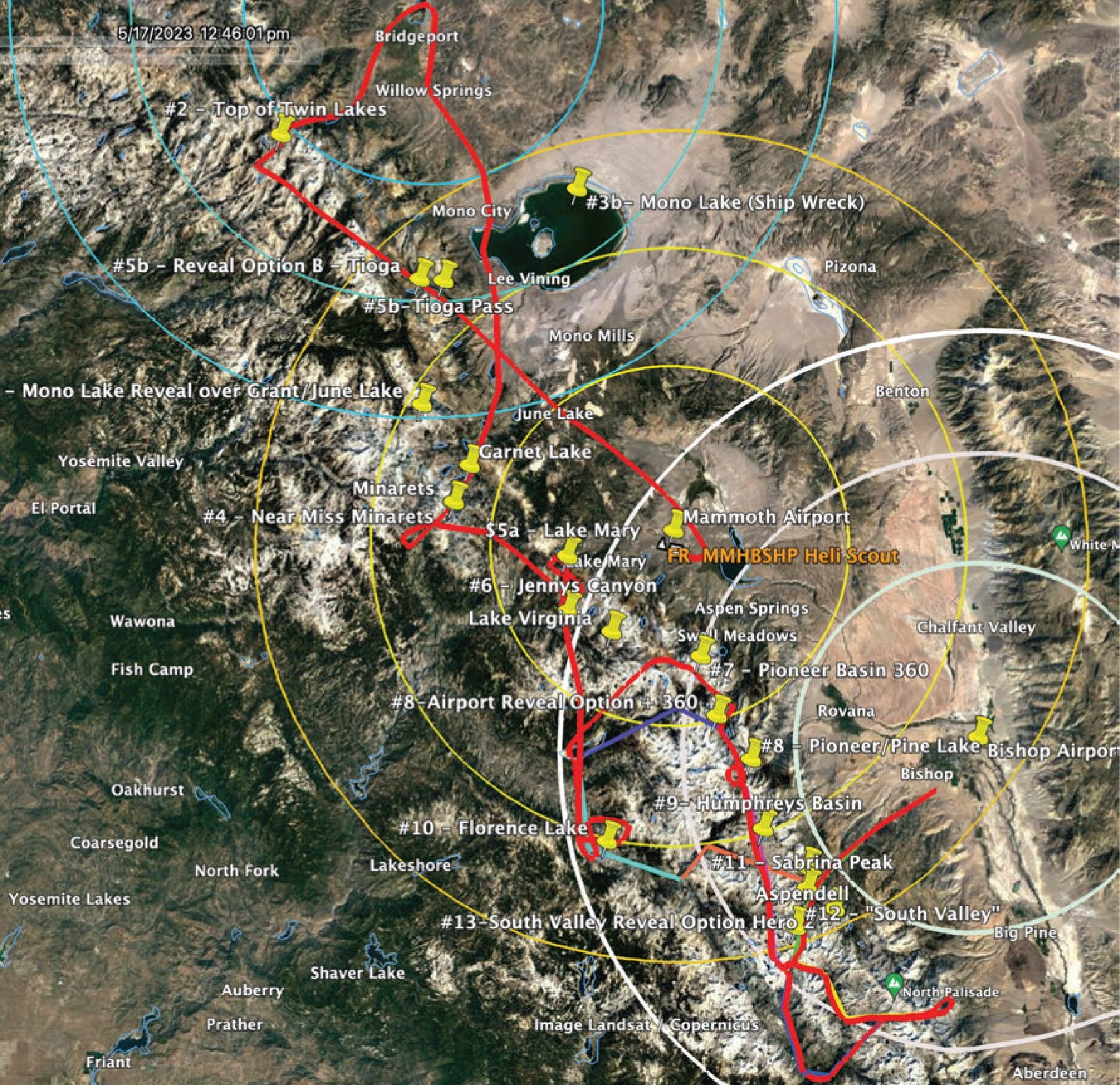

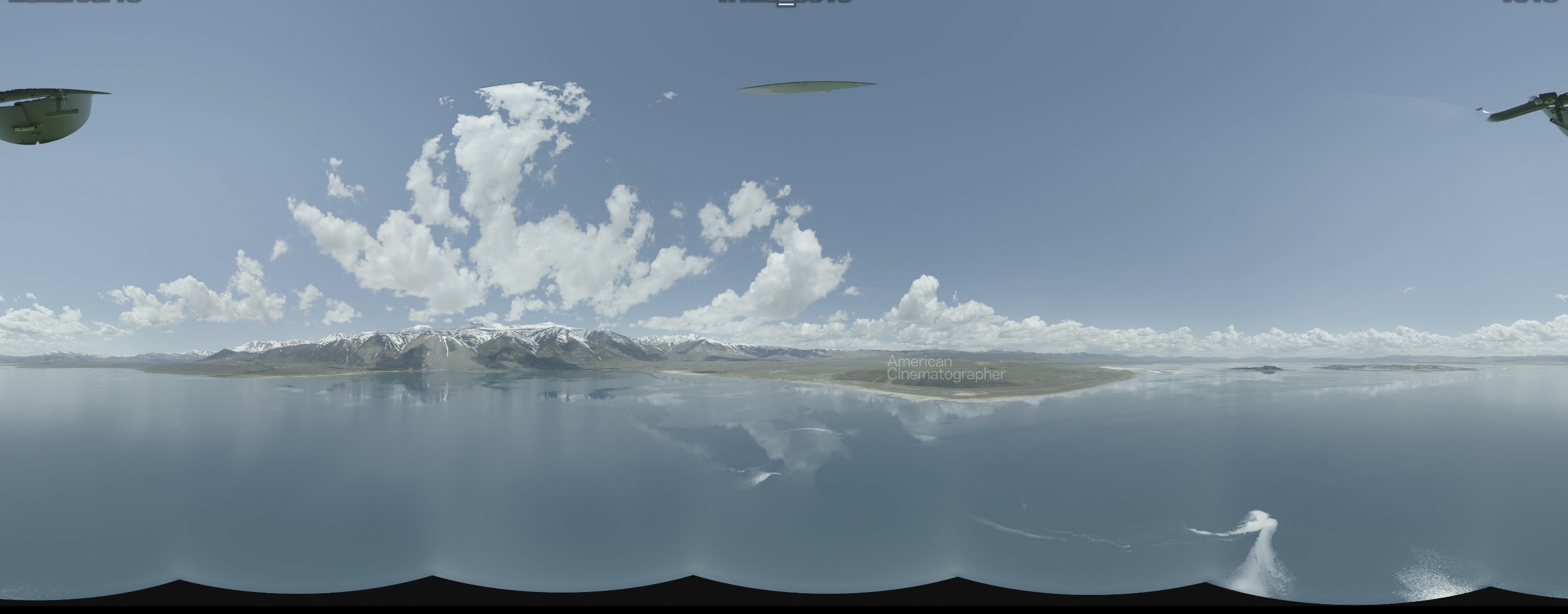

To capture the plates, the team employed “a custom long-line camera array, comprised of six portrait-mounted 8K Red V-Raptors paired with 15mm Zeiss CP.3 primes,” Ralla continues. “It was mounted to the bottom of a gyro-stabilized torpedo-like payload, which hung from a cable about 30 feet below a helicopter, just enough for the helicopter to be outside the array frustum. Wild Rabbit Aerial supplied an actively stabilized array system that integrates cameras and a stabilized head into one, while using a low-parallax pinwheel layout.”

After working out flight plans to capture story-appropriate landscapes from the script, the plates were acquired over three days, substituting the California High Sierras for Alaska.

Team5 Aerial Systems, with pilot Fred North and aerial cinematographer Dylan Goss, handled the flying, while Ralla supervised the flight path.

Google Earth-based previs and GPS-logged scouts precisely determined where the filmmakers wanted to shoot and at what time. Immediately after landing, Derango and Ralla showed the captured content to director Gibson “using recordings of onboard real-time stitches, mapped to script beats, and made selects for hi-res-content prep,” Ralla says.

Framestore Los Angeles, under the supervision of Paul Krist, created roughly 60 minutes of finished 360-degree stitched sequences for looped playback in the volume from the nearly five hours of captured plates.

“Lux Machina greatly expanded on the existing toolset of the Pixera playback engine, enabling additional CG overlays, on cue, to supplement the photographed imagery of the background plates,” Ralla notes. “So, elements such as clouds could be applied live during shots.” Derango enthuses that “the integration of on-demand CG clouds and practical SFX atmosphere were key in helping sell the illusion of being in the sky.”

Custom Stage

Because the production required LED walls larger than any existing stage the filmmakers could source, they used a massive rehearsal studio in Las Vegas to construct a bespoke, horseshoe-shaped LED-wall measuring 33' tall x 65' wide, with 270-degree circumference that created a 65'-deep production space. They used ROE Visual’s 2.8mm BP2 LED panels for the wall and diffused BP5s for the ceiling.

“Our production designer, David Meyer, worked out everything in [3D modeling system] Rhino 3D for the volume, [including] the plane buck mounted on a Nacmo six-axis motion-base gimbal, and what the camera would see at all the different angles we had planned,” Derango says. “We had 270 degrees of screen and plates with 360 degrees of coverage, so we could spin the perspective per shot. We could also spin the plane itself and tilt it up and down on the gimbal.”

There was no need for camera tracking, as the plates were 2D and the distance to any object in the footage was considerable enough to provide no sense of parallax. “Any theoretical absence of parallax will be perceptually compensated [for] by the fact that we’re flying at 200 miles an hour,” Ralla notes.

In-Flight Camera Techniques

Derango was determined to avoid capturing shots that would be impossible to film in an actual plane in flight. “There aren’t a lot of shots that are disconnected from the plane,” he says. “The majority of the movie is either inside the cockpit or hard-mounted to the Cessna’s exterior. We also built wild panes of glass with corners so we could put the camera up against the dashboard but still feel like we were inside the windows. It all helped build up the story’s claustrophobia and realism.”

A handful of shots required drastic changes in visual orientation, such as when the plane dives hard into clouds. “You just can’t get that sort of perspective from a long line suspended from a helicopter, so we’d switch to bluescreen for those and complete the plate in post,” Derango says.

Some shots called for looking directly into the screen to depict the pilot’s POV. This meant shooting straight into the LED wall — which is, of course, the Achilles’ heel of virtual production, as focusing on the wall creates immediate moiré in the image. “You have to set focus just short of the screen,” Derango says. “To the eye, it still reads as being in focus, but it’s not quite critical focus. We were also very conscientious about how close the plane was to the [LED walls] to avoid other potential moiré issues. We were never closer than 10 feet from the volume wall with the plane itself.

“One day, during prep, we were just getting set up, and I took a seat inside the plane. They had the plates running on the screen, and I thought, ‘This is amazing — it feels like we’re flying around.’”

“We did probably 50-50 single-to-dual-camera coverage,” the cinematographer adds. “Mel loves to shoot multiple cameras, but when you’re working in such a tight space, even with the Venice Rialto heads, there’s only so much room for cameras and operators!”

Derango notes that he and Gibson briefly considered shooting anamorphic, but “when you’re in a location that small, there’s no avoiding the lens ending up mere inches from an actor’s face at times. I knew close focus would be a huge issue for us and anamorphic lenses are not necessarily known for their close focus. They also tend to have more distortion and falloff around the edges than spherical. When you have three actors in a narrow-body plane, someone was almost always going to be on the edge of frame. Shooting spherical was a pretty easy decision to make.

“In regard to filtration, I used Tiffen Black Pro-Mists of varying degrees, along with polarizers. I’m a huge fan of controlling reflections and highlights with polarizers. For this film, I used roto-polas, which were wirelessly controlled by hand units at video village. This allowed me to quickly adjust highlights on actors’ faces or reflections in the glass windows of the plane. I was concerned that the polarizer would actually make the image on the volume disappear when rotated — as this happens often with computer displays and TVs — so it was the first thing I tested when our volume was up and running.”

Parting Shots

Derango found the overall immersion so effective that it fooled even his eye. “One day, during prep, we were just getting set up, and I took a seat inside the plane. They had the plates running on the screen, and I thought, ‘This is amazing — it feels like we’re flying around.’ Then the Lux team vertically moved the horizon around, and I grabbed my seat because it felt like the plane was falling off the gimbal. It was all a highly visceral experience for the crew and the actors.”

Asked if he would do anything differently on his next volume production, Derango says he would try to be more engaged during post. “Postvis — making sure the postproduction visual-effects teams can guide the editors about what’s in missing shots — was an area I wasn’t initially familiar with. For those shots, the editors are guessing what’s supposed to be there until they see the final effects shots delivered. The volume stuff is straightforward, but the more traditional VFX shots are a little trickier.”

Ralla notes that virtual productions succeed or fail based on the level of planning. “The key factor is the collaboration between the virtual-production team and the cinematographer,” he says. “At the start of production, Mel and Johnny expressed concern over hearing about other productions ultimately replacing much of their volume work because it didn’t look photorealistic enough. The challenge is that many virtual productions start out from a technical, ‘wouldn’t-it-be-cool’ perspective. For me, that conversation should always begin by asking the DP, ‘What do you want to see, and what will work for you?’ That, and the collaboration with Lux’s [chief technology officer] Kris Murray and his team at Lux Machina, ultimately made Flight Risk successful.”

Tech Specs

2.39:1

Cameras | Sony Venice, Venice 2; Red V-Raptor

Lenses | Panavision VA, Zeiss CP.3

Spotlight on Lighting | Supplementing the Ambience

To augment the ambient light emanating from screen content, Derango and gaffer Andy Lohrenz used Aputure Nova P600c, Nova P300c, LS 1200d Pro and LS 600c fixtures encircling the scene’s perimeter. “The Nova P600cs were primarily used in soft boxes rigged in a hexagonal pattern around the plane to provide ambient light through all of its windows, no matter the position of the plane,” Derango says. “The Novas were mapped to provide subtle effects for all the different location- and weather-related changes in the onscreen footage. However, they were not synced to the footage, so that we could maintain control over them ourselves. In a perfect world, we would have tested and found places for the lights to be synced, but unfortunately, our schedule did not allow for it. Thankfully, our lighting programmer, Elton James, was so fast, efficient and prepared that we found we could make quicker and more subtle adjustments when we had full control, rather than letting the footage dictate what was going on. Novas were also used from the ground when we needed fill light from the open end of the volume.

“The P300c and LS 600c were used primarily to up-light the airplane wings, simulating the ambient bounce from the snow-covered surface below, and sending ambience into the ceiling of the plane,” he continues. “Subtle effects and flickers were also added to help sell lighting changes when passing through clouds or into sunshine. We generally did not sync [those] to the screen [either], which allowed us the flexibility to fully control effects and levels. The 1200d Pros acted as our main direct sunlight, depending on plane orientation, and were never synced with the wall.

“Because of their small size, Aputure Infinibar PB3s and an Aputure MC Pro 8-Light Kit were primarily used inside the plane to add eyelights; soft edges; backlights; and, on a few occasions, supplemental reflective or ambient light in the cargo area. The plane was cramped and anything inside needed to be easily rigged and controllable. Because of their soft quality, [the fixtures] were primarily used as constant soft sources, and only occasionally were they used to supplement effects. These lights were never synced with the volume, either.

He adds that virtual light cards were deployed for additional fill and contrast control. “It was great because I could place each card exactly where it was needed and just slide it around whenever a bit of it came into the frame. We could even track and move the light cards within a shot to create light and shadows moving around as the plane banked.

“These white cards, black cards, ND cards and even gray cards were constantly adjusting. At any given time, we could have up to 10 different cards playing, giving subtle edge highlights to Topher in the passenger seat behind Mark. It was used additionally as a hair light for Michelle to separate her a little better from the background. These were instrumental on wide shots; we were able to get light into places where we would have never been able to with stands and without rigging.

These cards could be added anywhere in the volume, from ground level all the way to the top. We could create as large a shape as necessary, down to something as small as a 4-by-4 for an eyelight, 30 feet in the air. We could also use them to brighten or dim outside specific windows if the footage onscreen was a tad too dark or bright. Shooting multiple cameras on varied focal lengths simultaneously can prove challenging, but these cards allowed us the flexibility we needed to succeed.”

Aputure later published this behind-the-scenes video featuring Durango and his lighting approach: