Realism With A Master’s Touch: The Asphalt Jungle

Startling depth of field and dramatic perspective mark the photography of Asphalt Jungle, which Harold Rosson, ASC photographed almost entirely with a 35mm lens.

This article originally appeared in AC Aug. 1950

The Asphalt Jungle is a tautly-paced drama of the underworld that runs the emotional gamut from harsh brutality to quiet sensitivity. Its plot is based on the familiar chase pattern, but more specifically the pursuit by the law of a group of shady characters involved in a jewel theft.

It is the type of a story which, in less skilled hands, might have evolved into a run-of-the-mill melodrama — but favored by the incisive direction of John Huston, the outstanding photography by Hal Rosson, ASC, and top-notch performances by a uniformly excellent cast — the picture emerges not only as bang-up entertainment, but as a very artistic technical achievement as well.

“[Huston] wanted Jungle to have the look of having been filmed entirely in actual locales, without any studio atmosphere — and so we worked closely together to produce that effect.”

— Hal Rosson, ASC

It is Rosson’s craftsman like photography as much as any other element or combination of elements that makes MGM’s Asphalt Jungle an outstanding photoplay, for here is a film that leans heavily upon photographic mood in order to create its dramatic impact. For Rosson the filming of the picture was a particularly enjoyable experience in that it marked the first time in his lengthy career as a director of photography that he has been called upon to create so starkly realistic a style of photography. “It is a great tonic for a cameraman to work with John Huston,” he observes, commenting on the filming of the picture. “Huston is a man of very original approach. He knows what he wants but is very receptive to ideas and suggestions from his fellow technicians. He wanted Jungle to have the look of having been filmed entirely in actual locales, without any studio atmosphere — and so we worked closely together to produce that effect.”

The final product as it appears on the screen is indeed the result of very careful pre-planning by director and cinematographer. The picture’s title refers to a city (and not, as many people think, to the place where Tarzan used to hang out). But it was not important that the city be identified as any particular one — in fact, the producers preferred that the city be unidentified. With this in mind, and because the original script called for a waterfront locale, Huston and Rosson scouted locations in St. Louis and Cincinnati. After several weeks of scouting, it was decided that all of the scenic requirements could be met on the West Coast — so with the exception of one shot, all of the metropolitan shots were made right in Los Angeles.

For filming these scenes the studio received the close co-operation of civic authorities so that various areas could be roped off. Many of the sequences, as demanded in the script, were filmed in the early morning hours when the deserted streets lent further atmosphere to the situations.

In shooting the picture, Rosson avoided the usual “documentary” style of photography, which has become a kind of vogue since World War II. With all due respect to those who have achieved great cinematic effects through the use of this unvarnished type of photography, it can also be said that much downright poor photography has slipped by with the excuse that it is documentary. Rosson proves in this picture that a craftsman who knows his tools can combine realism with the kind of technical finish one has come to expect of Grade A studio product.

“I think of the camera as a member of the cast — an actor, and as such it must play its part and give the finest possible performance.”

To Rosson, who for years has been considered one of the top “glamour” cameramen in Hollywood, the lighting requirements of Asphalt Jungle presented a challenge and called for a complete departure from anything he had ever done. Accustomed to having to consider the “best side” of this or that star’s face, as well as the necessity of eliminating double chins, crows feet and the ravages of stellar hangovers, it was a refreshing experience to be given a cast of good actors who were not name stars and who did not have to be glamourized on the screen.

With the exception of Marylyn Monroe, who plays the part of a bush-league Lana Turner and is therefore given the full benefit of glamour lighting, all of the players were photographed as realistically as possible. In the case of the feminine lead, an exceptionally attractive actress named Jean Hagen, it was actually necessary to play down her good looks so that they would not detract from the drama of her characterization.

In lighting the picture, Rosson took into consideration the fact that the underworld has a peculiar glamour all its own — a harsh, sinister, ominous quality that warns of danger lurking in every shadow. He lighted each set to simulate light sources natural to the particular locale, and in so-doing he let the shadows lie where they would naturally fall. This meant that instead of having to light his players so that they would be fully illuminated throughout the entire pattern of action in the sequence, he could light the set with perfect realism and let the players play in and out of the light as they would in the actual situation. In some cases the actors went completely into silhouette, an effect which added greatly to the drama of the sequence.

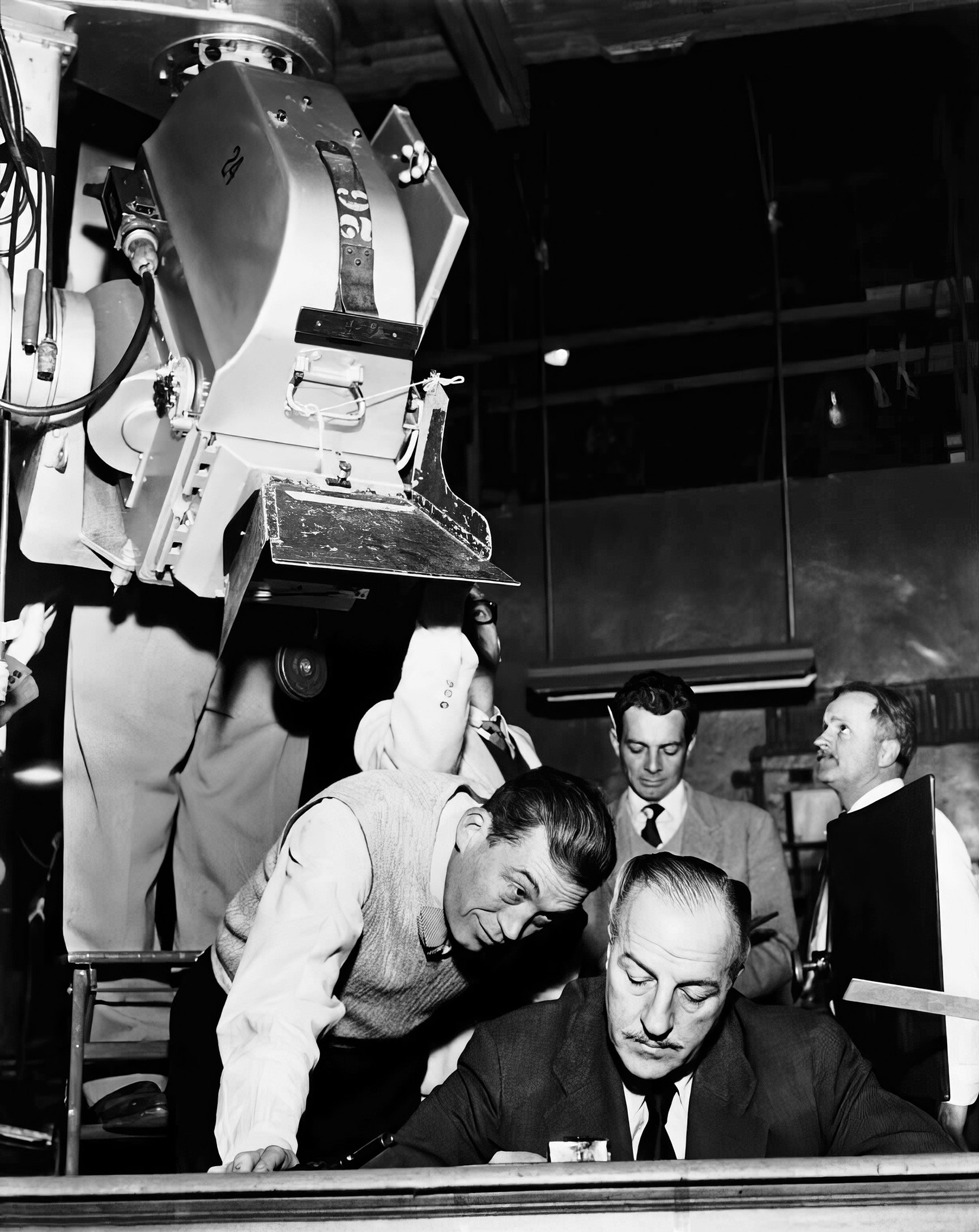

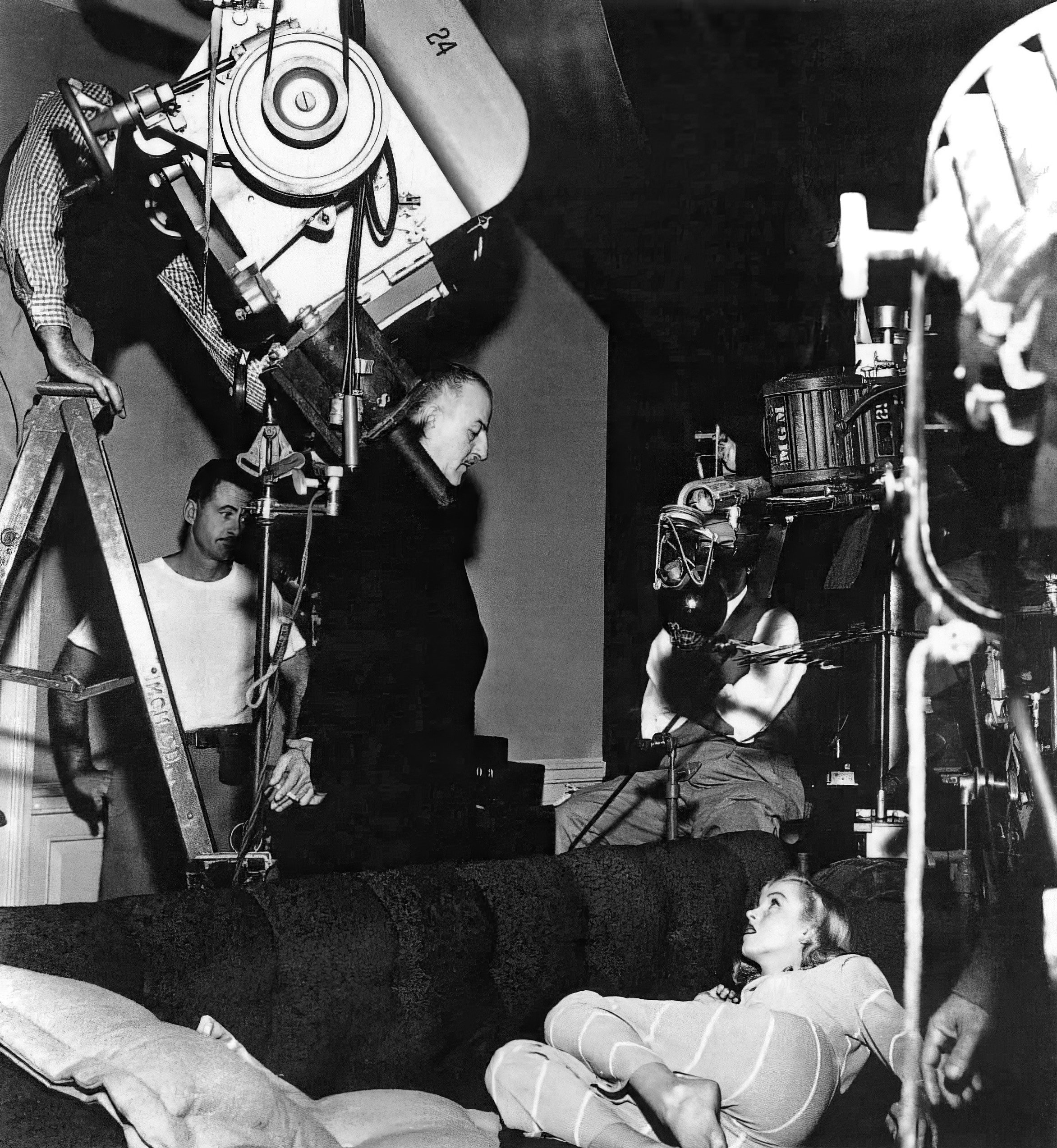

Almost the entire picture was filmed with a 35mm lens in order to achieve the desired depth of field as well as dramatic perspective. The depth factor assumed unusual importance because director Huston staged much of the action with players prominent in the foreground, but with important action also transpiring in the background. In order to hold both of these widely separated planes in sharp focus, it was necessary to use unusually high light levels and stop the lens down for greater depth of focus. The trick in this type of filming is to match a scene shot at f.2.8 with one shot at f.5.6 for the same sequence — retaining, for example, the same degree of luminosity in the walls of the set while keeping the key of the lighting identical in both shots. When a lens is stopped down in this fashion there is a natural tendency toward increased contrast, and some skillful calculation is required to keep all of the light values in balance to match scenes shot at a wider aperture.

Rosson used low camera angles extensively in Jungle in order to emphasize the dominant character of the underworld personalities portrayed, and such shots were particularly effective in sequences where the action is played from planes far back on the set on up to closeups. An added problem in such shots was the fact that ceilings had to be used on the sets, thus making light placement more difficult.

The process of latensification [intensification of a latent photographic image by chemical treatment or exposure to light of low intensity] was widely employed in this film in order to permit realistic lighting of night exterior scenes. With this method it is possible to photograph scenes with a great deal less light, or by means of light natural to the locale. In the case of the night exteriors it was possible to shoot with far less illumination than would ordinarily have been required, and the effect is more realistic.

In one instance, latensification permitted the filming of a sequence that otherwise could not have been captured on film. Part of the chase takes place through a tunnel approximately 300 feet long, three feet wide, and six feet high, with smooth concrete walls and no recesses in which to hide lights. The only illumination comes from small bare bulbs used to light the tunnel, but these were sufficient to get an exposure when shot with film that was later latensified.

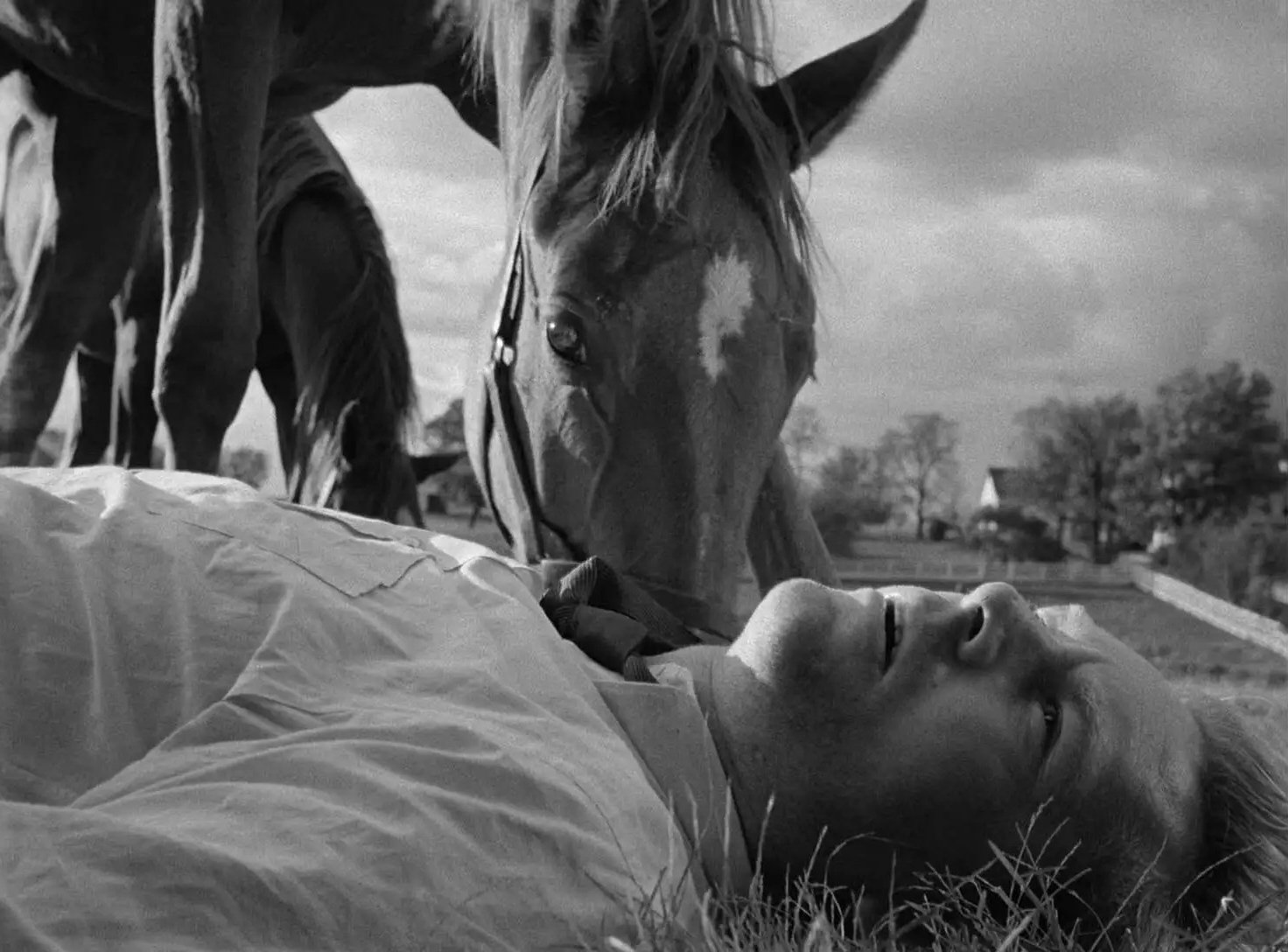

After all of the harshly dramatic low-key interiors it was a welcome break for Rosson to go to Kentucky to film the beautiful sun-lit horse farm which is the locale of the picture’s final sequence. It is in a meadow, surrounded by peacefully grazing offspring of War Admiral, that the protagonist finally dies, thus fulfilling the moral of the story and the demands of the Johnston Office. [Editor's note: This refers to the Motion Picture Production Code, at the time run by Eric Johnston.]

A veteran of more than 30 years in motion pictures (the last 20 of which have been spent at MGM), Hal Rosson has filmed many outstanding successes. Among his own favorites are: Captains Courageous, The Scarlet Pimpernel, The Ghost Goes West, and all of the Clark Gable pictures. He recently completed Gable’s latest, the as yet-unreleased To Please a Lady. Prior to the war he filmed many pictures in England for Alexander Korda as well as for MGM, including Things to Come and A Yank at Oxford. He is now preparing The Red Badge of Courage, a Civil War story in which he will again team with director Huston.

In approaching a screen story Rosson reads the script carefully, mapping out the camera’s role in each sequence, as well as in the establishment of mood and style for the entire picture. “I think of the camera as a member of the cast — an actor,” he explains, “and as such it must play its part and give the finest possible performance. It is my job in directing this particular actor to get the best from it.

“Jungle was one of the most interesting pictures I’ve ever been privileged to work on, and it was made especially pleasant due to the unusual teamwork and enthusiasm of the cast and crew. Each evening, all of them voluntarily stayed an hour or so late to crowd into the projection room and view the previous day’s rushes. How do / feel about the picture? Well, if in 20 years someone asks me to name the favorite pictures I’ve worked on, I’m sure that Asphalt Jungle will stand right at the top of the list.”

In 2016, The Criterion Collection produced this video commentary for their release of the film, featuring John Bailey, ASC and his thoughts on the production:

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.