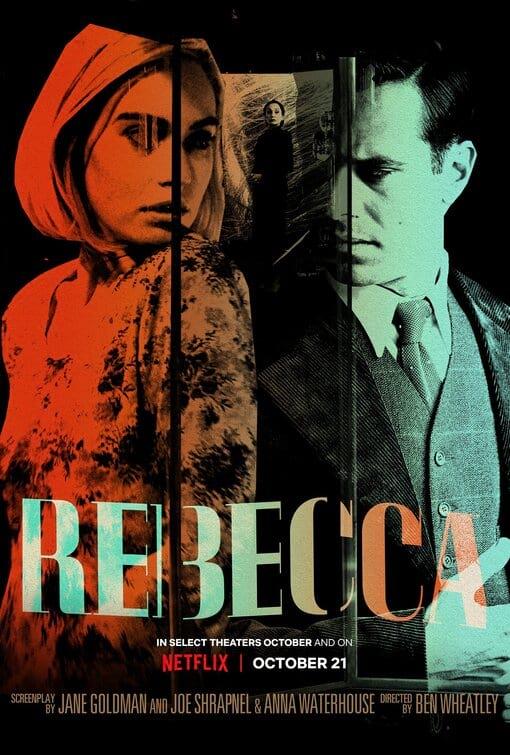

Rebecca: Revisiting Manderley

BSC member Laurie Rose shoots a new screen adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s classic novel.

Photos by Kerry Brown, courtesy of Netflix.

In 50 years, the dawn of the streaming broadcasters might be remembered as another golden age of cinema. Right now, the fight for dominance is funding a huge range of productions that demand carefully applied craft and also, increasingly, the big guns of modern production technology: larger sensors, HDR, 4K and beyond. Sometimes, though, that drive for high-spec moviemaking meets a simultaneous desire for classical pictures that evoke a period setting; bringing those two elements together became the responsibility of cinematographer Laurie Rose, BSC on Rebecca.

Daphne du Maurier’s novel — on which this production is based — follows the young new wife (played by Lily James) of a wealthy widower (Armie Hammer) as she uncovers dark secrets about his late spouse, Rebecca, under the stern glare of forbidding housekeeper Mrs. Danvers (Kristin Scott Thomas). Rose describes the source material as “a venerable piece of English literature. I’ve always liked a bit of du Maurier, and I especially enjoyed what my fellow BSC member, Mike Eley, did more recently with My Cousin Rachel. The writing is so fantastic.”

Though Rebecca — streaming now on Netflix —would shoot mainly outside of London, AC found the production unit hard at work in a location off Tudor Street on the balmy night of August 3, 2019. In the scene underway, James’ character visits a doctor during her investigations into the wife who preceded her, in an attempt to clear her husband’s name. A small corner of London had been taken 80 years into its own past, this time a SkyPanel S360-C suggesting steely moonlight from its perch atop a cherry picker and an array of PAR cans simulating the historically warm glow of receding streetlights.

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 screen adaptation — photographed by eight-time Oscar nominee George S. Barnes, ASC — took the Academy Award for best black-and-white cinematography that year. “I hadn’t seen the Hitchcock Rebecca for some time,” Rose says, noting that his prior collaborations with this adaptation’s director, Ben Wheatley — which include the features Free Fire, High-Rise, A Field in England, Sightseers and Kill List — were not at all typified by somber period drama. “My love of film stems from my mum being a big fan of the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s eras of filmmaking, but when Ben and I started talking about Rebecca, it might have seemed a bit off our path. And yet that’s what made it such an interesting prospect — to be able to get some budget and also work with Working Title. It was a different world for us to exist in.”

The movie’s world comprises three distinct parts, all set in a 1930s milieu of wealth and privilege but ultimately yielding very different looks. “There’s the summer holiday romance at the beginning, all set in the South of France, when [the couple’s relationship] is meant to be idyllic, charming and beautiful. Then they crash back into the U.K. for the second part of the story — the wetter, dreary, more Gothic part when Mrs. Danvers arrives, and we’ve got the character of the old house and a kind of ghost story. The third part, which is quite short, is when our new Mrs. de Winter undergoes an emotional change, grows up and develops a darker side. It’s the detective story where she takes control of her destiny, for good or bad.”

Rebecca was shot on Arri’s Alexa 65, a new camera to Rose. “I’m very excited about it,” he says. “Russell Allen and Simon Surtee at [Arri Rental] London were very helpful and couldn’t do enough for me.” While the camera’s huge 6.5K sensor provided a generous canvas, Rose treated it as a foundation, upon which he could build period-appropriate imagery using several techniques. “More and more, with bigger sensors and higher resolutions, I want something a little bit vintage on the front of a digital camera. I want character, texture and soul. I do that with a bit of onboard ISO. I shot Rebecca at 1,280 or 1,600, because the big sensor has so much latitude. It can handle that high-ISO approach, which puts a bit of grit into the images.”

To aid in his pursuit of a less clinical picture, Rose chose Arri’s Prime DNA lenses, which the company describes as being based on “vintage optics from different historical periods.” Shooting ArriRaw at 5.1K removed some of what Rose calls the “wild edge artifacts” of the DNA lenses; the show’s B camera, an Alexa LF, recorded in 4.5K Open Gate, also in raw. Special permission was granted by Netflix to frame for a 2.39:1 aspect ratio, as opposed to the 2:1 ratio the distributor usually prefers. Rose operated the A camera personally, with James Layton alternating B camera and Steadicam.

“The DNAs are an ongoing project for Arri, and they are somewhat tuneable to taste,” Rose notes “I had a couple of 50mm and a couple of 80s; one was a red-dot variant. It had a little engraved red dot and it had the most beautiful sweet spot and fall off and flare aspects that were a world apart from the rest of the set — it was one that I’d go to really regularly. Our go-to lenses were the 35, 40 and 80mm. I’d go to the 80 because it just looked stunning. I almost asked if I could just have a whole set of red-dot variants.”

There is some mystery behind the lenses. “We were talking about the tuning, and when I asked Arri what they’d done with the red-dot variants, they said DNA stands for Do Not Ask! There’s an element of experimentation, and that’s what’s lovely about those lenses.”

Manderley.

Rose put the finishing touch on his camera setup with Schneider’s Hollywood Black Magic filters. “I really like them, but I only used them very sparingly. You don’t want to overdo these things — eighths and quarters only. Coupled with the DNAs, which are quite textured and interesting vintage-feel lenses with modern mechanics, the filters really gave me the look of ‘holiday romance’ that I was going for [in the early scenes]. Lenses and filters only added to the Alexa sensor rendering dreamy skin tones and color.”

Beyond the tech, Rose expresses his clear respect for the show’s Oscar-nominated production designer, Sarah Greenwood. “Sarah designed Atonement and, more recently, Beauty and the Beast, Darkest Hour, many of Joe Wright’s projects. There’s just an astonishing amount of period detail [in those films]. The scope and scale, the lengths they went to, were astonishing. What I love most about production design is when they create these universes for us to prowl around in with a camera. It’s a joy.”

Rose adds that Greenwood was also heavily involved in the choice of locations, which included a variety of settings in both the U.K. and France. A sumptuous hotel seen early in the film was “a real Victorian hotel. It’s an apartment building now, but it still has that area that was originally a lobby. It was a super-grand entrance hall that we filled with period fixtures.”

The location presented its own problems, though, with “incredible windows that were good and bad. Immediately outside the lobby is a conservatory, a glass interior eating area with a terrace immediately beyond, where the couple have breakfast together.”

Lighting this area was complicated by the local topology: “There’s a 12-foot drop off that terrace into the street, which was crossed with a bridge — the same street you see in the show when their car drives up — and I had to light from that street. We had to get bigger machines than we normally get, truck-based cherry pickers.” Other equipment included a SuperTechno 50 crane, transported to the Nice location from a depot in Munich.

None of the hotel’s interiors, other than the lobby, were actually shot in France. Scenes featuring Mrs. Van Hopper (Ann Dowd) were shot at Waddesdon Manor — a location so beautiful, according to Rose, that it “barely needed dressing. But a lot was shot in stunning heritage houses, where the caretakers are rightly wary of film crews. Often you’re not allowed to use smoke, and I wasn’t at Waddesdon. We could do that in France — they were less precious about that in the hotel — but I categorically wasn’t allowed to use it in the apartment, which was tricky for continuity.

Rebecca has a plot that’s overwhelmingly influenced by its setting: the fictional Manderley, an English country home that assumes an almost mythical portent as the story progresses. Rose says Wheatley was intent on making Manderley feel labyrinthine and unknowable, so the house was constructed from “five or six locations that were pieced together to create this infinite scale for the setting. That was a challenge because it involved a lot of travel. The sense of walking out of one room and into another was spread out over a lot of locations.” Those locations included Cranborne Manor in Dorset, Osterley in west London, Mapperton in Dorset, and Hatfield in Hertfordshire.

One of Hatfield’s larger spaces was disguised with extensive flats for a party scene, but also provided grand hallways. “The windows were amazing,” Rose recalls, “and there’s a lot you can do without using anything at all. The interiors are relatively dark, so you have your contrast sorted out.”

The house itself also offered some practical help, particularly in the library, “where we did a last-minute walk-through scene. Due to access, I couldn’t get any lighting into that room from outside, so we went with available light, but the room did have roller blinds that we could use almost as dimmers. My chief lighting technician, Julian White, would clip very lightweight diffusion or very lightweight blackout to the roller blinds. You can bring them down and reduce the light in the room, or have the light coming from the bottom of the window only — it’s a fast and non-invasive use of controlling what you have at hand!”

Splendor aside, Rose and his team faced a need to make scenes set in England feel noticeably different than those set in France. But the weather in England, Rose recalls, was “not quite how we wanted it. We shot in high summer, but we really wanted the feeling to be autumnal, October, a bit more ‘England.’”

Scenes at the high point of the story take place at a coastal location, represented by Hartland Quay in Devon, requiring Rose to light an entire bay. “We had a lot of firepower out that night,” he says. “The cove was about two kilometers across. I had five 18Ks that were giving me a level on the cove, the biggest area I’d ever had to light. We also used a fantastic new system called TommyBars — an array of 16 8-foot LED bicolor tubes.”

Deploying those tube arrays had some practical benefits. “Because they’re without textiles, they don’t act like a sail. Often you’re building moon boxes with diffusion, and that’s naturally subject to wind. Our concern of working on that windswept coast was solved with the weatherproof TommyBars, which gave me an overall ambient ‘moonlight’ along with the cove background. And then our heroine approaches the boathouse using an LED-supplemented oil lantern.”

The globetrotting narrative finally reaches Cairo, punctuating a character point for James’ unnamed protagonist. The setting is “a bedroom where she wakes up and walks across to the mirror. Her transformation is complete and you see her smoking; she’s a character who’s lost her innocence.”

The filmmakers tried to find a location in the South of France that might double for an Egyptian bazaar, but the scene was eventually shot at the Leighton House Museum in Kensington, London. “Cairo is a greenscreen outside the window! We put in a single 24K tungsten unit, and we were luckily allowed atmos [smoke] to complete the sundrenched dusty heat.”

Rebecca was finished by Goldcrest colorist Rob Pizzey, whom Rose considers “a long-term collaborator. He makes anything I throw at him look astonishing, so I’m in gratitude to Rob.”

The production’s shooting schedule was achieved over a relatively compact 50 days, and with such a breadth of locations, Rose describes the shoot as “very, very busy. We weren’t at many locations for very long at all, which was a real challenge. I think the film has a certain pace and sophistication, though, and the story feels as if it covers a lot of ground. A lot goes on, and it all feels quite deep and profound.”