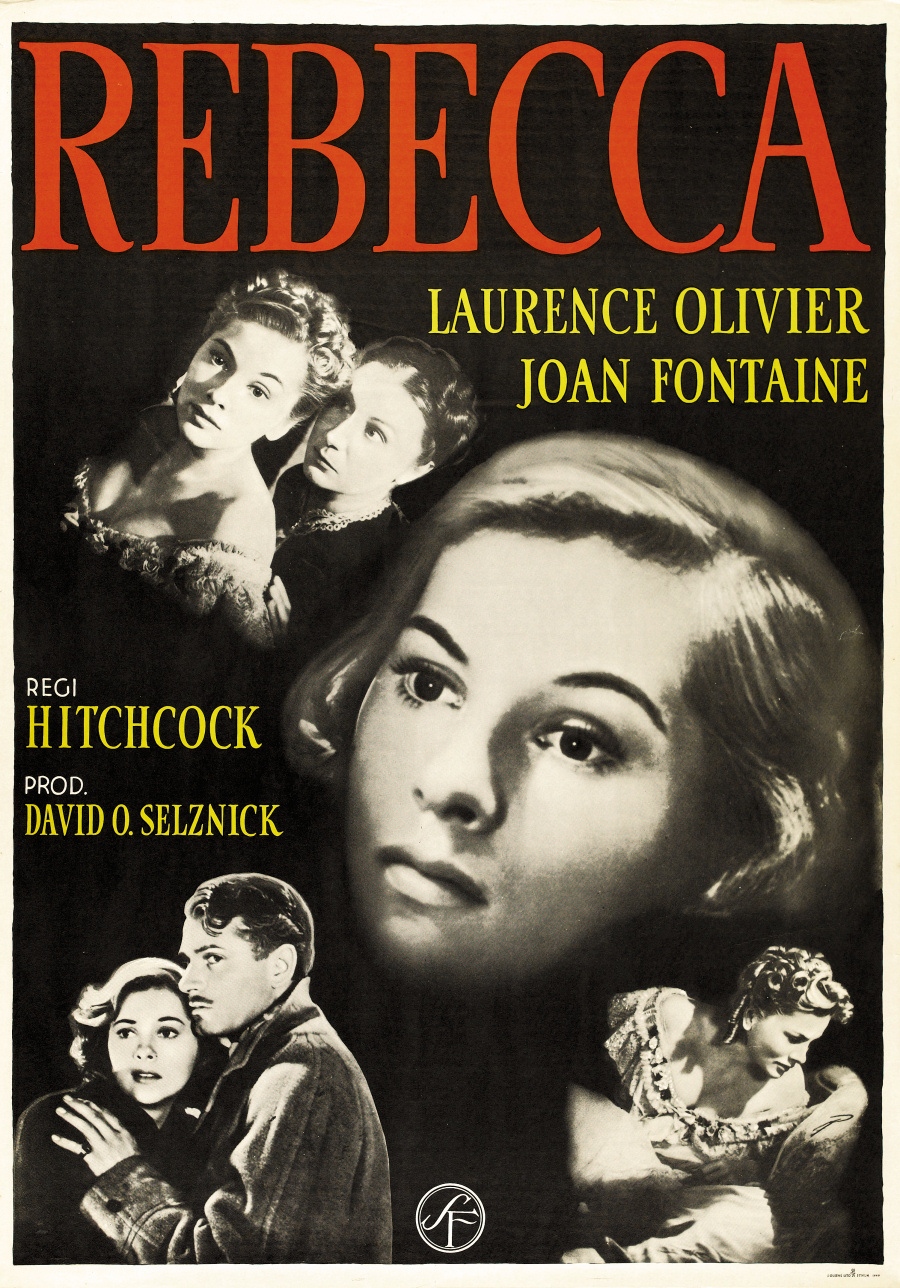

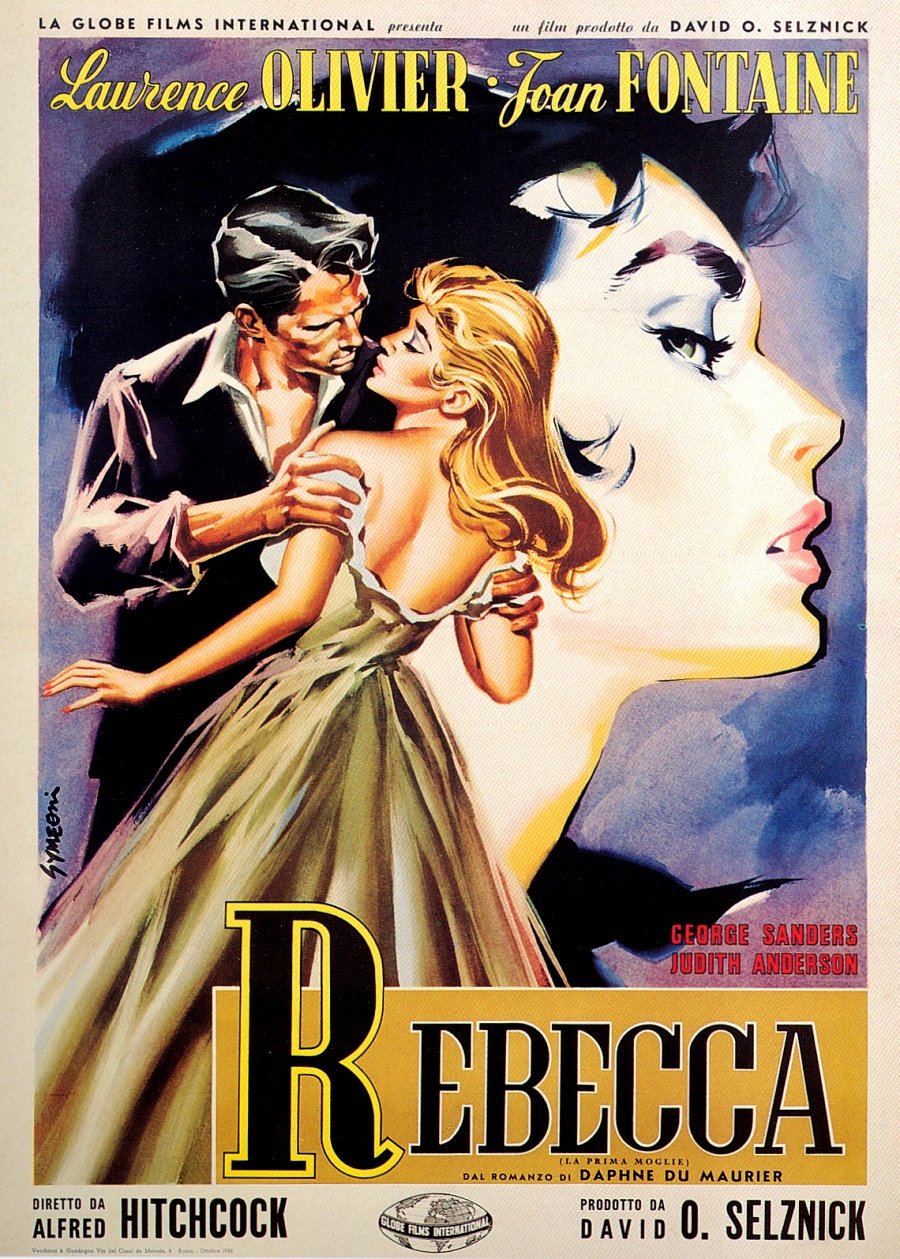

Du Maurier + Selznick + Hitchcock = Rebecca

Disparate elements combine to deliver a classic exercise in atmospheric suspense.

This article originally appeared in AC July 1997. Some photos are additional or alternate

“I’ve a feeling that before the day is over someone is going to make use of that old-fashioned but somewhat expressive term foul play,” drawls the inimitable George Sanders in David O. Selznick’s production of Rebecca. With Alfred Hitchcock directing, of course, foul play could be expected.

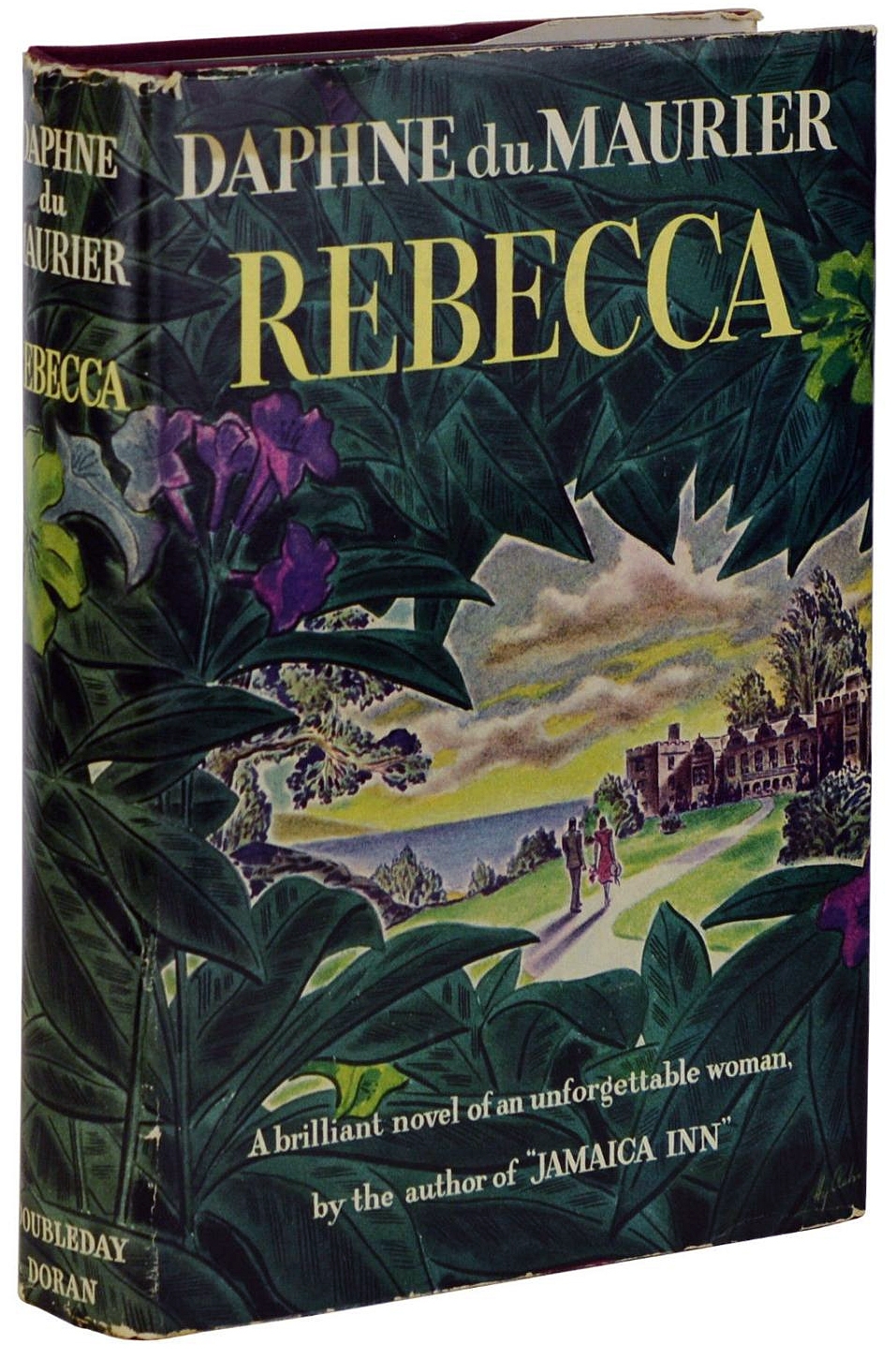

Rebecca began in 1938 as a novel by Daphne du Maurier. The book captured the attention of Hitchcock, the British director who had built his reputation as the “master of suspense” with melodramas such as The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) and The 39 Steps (1935). After glancing through galley proofs at Elstree Studio while directing The Lady Vanishes (1938), he considered buying the property, but decided that the price was too high.

Kay Brown, East Coast story editor for Selznick, sent a synopsis to her boss with the highest recommendation. After consulting with his resident story editor, Val Lewton, the producer acquired the film rights to du Maurier’s book for a hefty $50,000.

The novel is told in the first person by an unnamed young woman, a shy paid companion to the gross Mrs. Van Hopper, who is on holiday in Monte Carlo. There, “I” meets moody Maxim de Winter, a wealthy English widower. They marry and return to his estate, Manderley, which seems haunted by memories of the beautiful Rebecca, the first Mrs. de Winter, who supposedly drowned the previous year while boating alone. The new bride grows increasingly terrified of the housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, whose abnormal devotion to Rebecca makes her hate her new mistress; she even tries to coax her to commit suicide. The discovery of Rebecca’s corpse in her scuttled boat casts suspicion on Max, who had identified another body as Rebecca’s. Max admits to his wife that he killed Rebecca when she boasted that she was pregnant by one of her lovers. A doctor reveals that Rebecca had learned that her supposed pregnancy was actually terminal cancer. The coroner rules death by suicide. Rebecca’s lover, Favell, telephones the news to Danvers, who goes berserk and burns Manderley to the ground, dying with it. The de Winters find happiness elsewhere.

Although Selznick wanted to be faithful to the novel, the censors demanded that Max could not kill his wife without paying the penalty. Suicide was also frowned upon. After a hard-fought but futile battle, Selznick had to settle for Rebecca being accidentally killed when she falls while attacking Max.

Selznick, son of pioneer producer Lewis J. Selznick, had presided over many distinguished films at Paramount, RKO Radio and MGM. In 1936, he leased the RKO-Pathé Studio in Culver City, renamed it Selznick International Pictures, and bannered his credo: “In a Tradition of Quality.”

Built in 1919 by Thomas Ince, the studio had both modern and antiquated stages and shops, a colonial-style administration building and a 40-acre backlot. There Selznick produced such admirable films as The Garden of Allah, A Star is Born, The Prisoner of Zenda, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and others. In 1938-’39 he made the most popular movie in history, Gone with the Wind, a Herculean effort that left him exhausted and subject to wide mood swings. Selznick labored ever after in the shadow of GWTW, agonizingly aware that he would never surpass it. Of the 11 films that followed during his career, only Rebecca approached it in prestige or popularity.

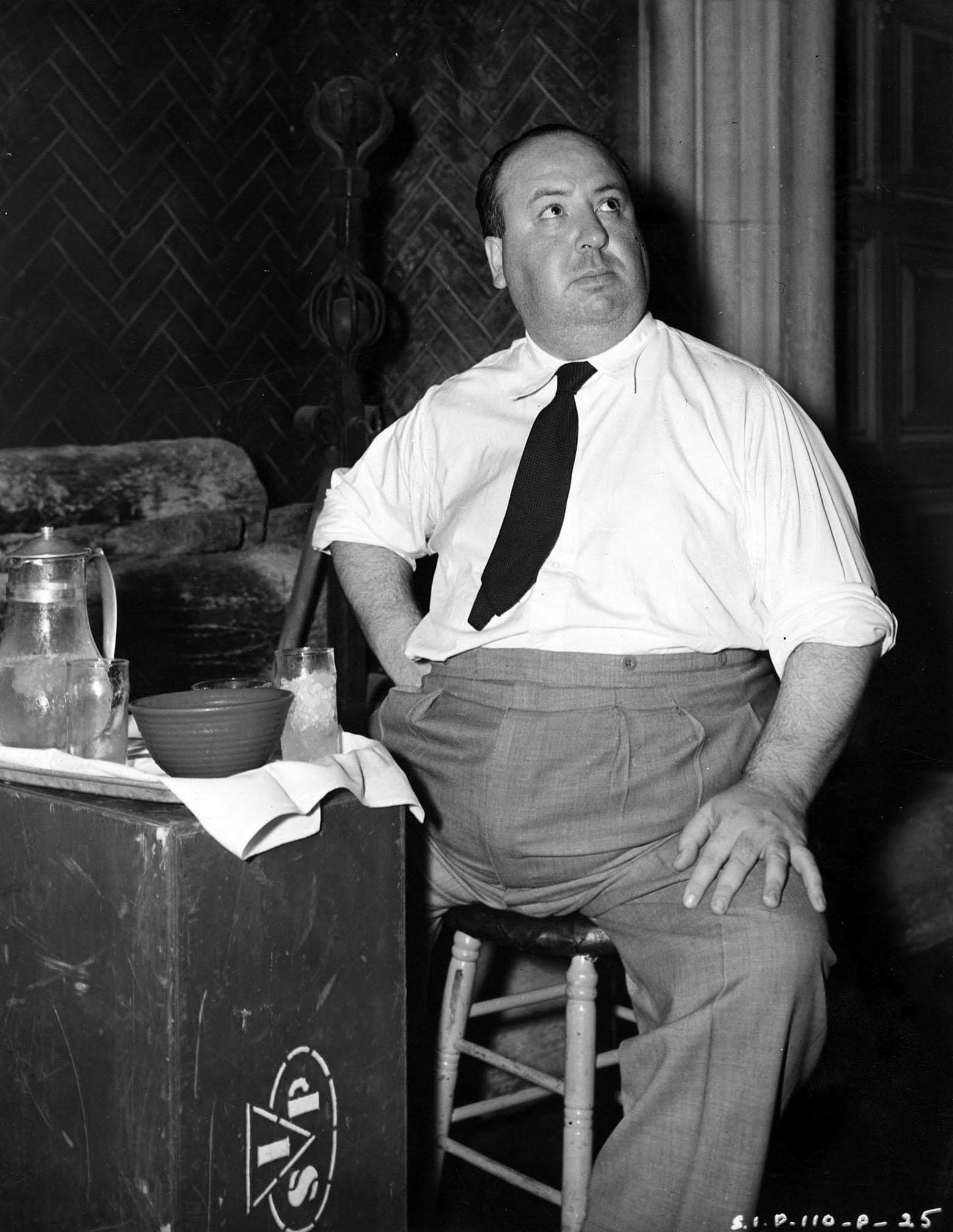

“I shall treat this more or less as a horror film.” — Alfred Hitchcock

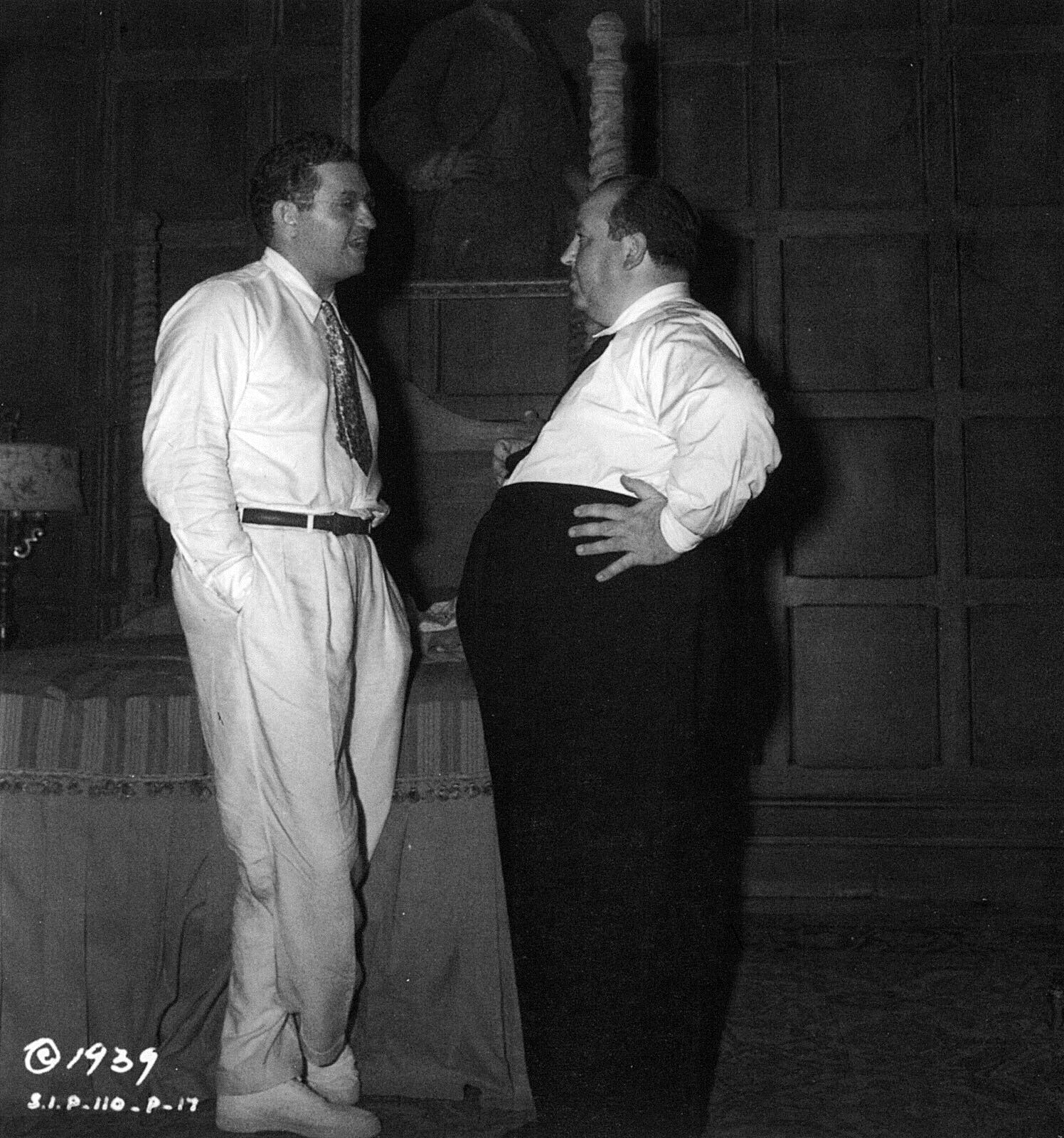

Hitchcock had long fantasized about making pictures in the United States with famous stars. Through Selznick’s agent brother, Myron, he negotiated a contract with Selznick effective July 14,1938. Hitchcock’s first assignment was to be The Titanic, but in September he was named to direct Rebecca. The teaming of the most autocratic of producers with the most independent of directors made head-butting a way of life for both. Somehow, from this monumental mismatch, a great movie emerged which exhibited the distinctive artistry of two very different men. It also showcased the work of an outstanding production crew and the finest work of a brilliant cast.

Du Maurier ranted that she hated Hitchcock’s version of Jamaica Inn (1939) which reflected his cavalier attitude towards source material. Selznick asked her to write the screenplay, but she refused.

To Hitchcock, even an international best seller was nothing more than a springboard for his own ideas. “This is really a new departure for me,” he said in the November 5, 1938 edition of Film Weekly. “I shall treat this more or less as a horror film, building up my violent situations from incidents such as one in which the young wife innocently appears at the annual fancy-dress ball given by her husband in a frock identical with the one worn by his first wife a year previously.”

Du Maurier needn’t have worried: Selznick demanded that the novel be followed faithfully. When he saw the first treatment, which was prepared under Hitchcock’s supervision by distinguished Scottish author Philip MacDonald and Hitchcock’s former secretary, Joan Harrison, Selznick flew into a rage. In a 10-page letter dated June 12, 1939 (which can be found in Memo from David O. Selznick by Rudy Behlmer) he told Hitchcock he was “shocked and disappointed beyond words” at the “desecrations” of their “distorted and vulgarized version ... We bought Rebecca and we intend to make Rebecca.”

Hitchcock, Harrison and Michael Hogan quickly prepared a version that passed muster. Later, Selznick hired playwright Robert E. Sherwood to prepare the final script.

Selznick was again outraged when Henry Ginsberg, vice-president and general manager, submitted a budget of $947,000, based upon the total estimates of all department heads. Calling it “a disgrace,” Selznick declared that the head of any department that did not stay within a sensible budget “is going to be fired ... If there is going to be any extravagance in our picture-making it is going to be indulged in by me personally to improve the quality of pictures, and I am not going to have it thrown away through sloppy management.”

The casting of the lead roles proved difficult. Selznick had bought the property for Ronald Colman, whose contract for The Prisoner of Zenda called for a second picture. Colman, who likely would have been the perfect de Winter, balked because he thought his public wouldn’t like him as a murderer, and because he feared that Rebecca would emerge as a “woman’s picture.” Hitchcock also tried vainly to convince Colman to take the part.

After considering such top stars as William Powell, Leslie Howard and Melvyn Douglas, Hitchcock and Selznick agreed upon Laurence Olivier. The British Shakespearean actor had just scored a hit as the brooding Heathcliff in Samuel Goldwyn’s Wuthering Heights, and his asking price was $100,000 less than what MGM wanted for Powell, their first choice. Olivier was signed in June of 1939.

It happened that Olivier was the paramour of Vivien Leigh, who was finishing Gone with the Wind. She quickly began to badger Selznick for the role of the second Mrs. de Winter. She made a screen test with Olivier and was, Selznick noted, “terrible.” After she and Olivier returned to London in midsummer, she made another test there and air-expressed it to Selznick.

Selznick wanted Hitchcock’s former protege from England, Nova Pilbeam, for the part. Hitchcock, who preferred an American star, finally talked Selznick out of it. Hitchcock, John Cromwell and Anthony Mann were directing tests of about 30 other actresses, with contract actor Alan Marshall standing in as de Winter. Some were impressive, particularly established stars Margaret Sullavan and Loretta Young, and a very young New York actress, Anne Baxter. George Cukor suggested Joan Fontaine, whose previous film roles had been unimpressive, and she made several tests.

Selznick eventually decided that he wanted Fontaine’s sister, Olivia de Havilland, for the role, but when de Havilland learned that Fontaine was being considered for the part, she refused to be tested.

By mid-August, the candidates had been narrowed to Sullavan, Hitchcock’s choice; Fontaine, Selznick’s choice; and Baxter, the staff’s popular favorite. Selznick finally eliminated Sulla van with the line, “Imagine Margaret Sulla van being pushed around by Mrs. Danvers right up to the point of suicide!” Baxter was dismissed as being too young and too difficult to photograph. Over the Labor Day weekend, against the advice of almost everyone, Selznick decided to use Fontaine.

For the role of Mrs. Danvers, the choice was Judith Anderson, a haughty and demanding stage actress from Australia. The supporting cast could hardly be better. It is difficult to imagine anybody but George Sanders as Favell, the charming, lip-curling scoundrel. There is also the unforgettable Florence Bates as Mrs. Van Hopper, and such sturdy Britishers as Nigel Bruce, Gladys Cooper, Reginald Denny, C. Aubrey Smith and Leo G. Carroll.

During this time, contract cinematographer Harry Stradling Sr., ASC had started shooting Intermezzo: A Love Story for Selznick. The producer was displeased with the closeups of his new star from Sweden, Ingrid Bergman, and replaced Stradling with Gregg Toland, ASC. After being assigned to Rebecca, Stradling sent Selznick a teletype asking to be released from his contract because “with the mental strain of wondering whether I was satisfying you and with thoughts of being taken off the picture, I honestly don’t feel I could do justice to you and your organization in making Rebecca.”

Selznick ordered Ginsberg to get Toland, whom he felt would be “worth his weight in gold to Rebecca. I will be agreeable to paying a very fancy bonus for having him on the picture. I don’t feel there is any other cameraman in town comparable with him for this job — and while there may be other men of equal ability, they would take twice as long to get the same result.”

Toland wasn’t available, but his long-time mentor, George Barnes, ASC, was. He brought to the picture a wealth of artistry and experience that assured a first-rate job— and he worked fast.

The sets for Gone with the Wind were still in use when construction began on the 40 settings Lyle Wheeler designed for Rebecca. As soon as a GWTW set was struck, a Rebecca set grew in its place. Twenty-five were interiors, mostly of Manderley; others included the boathouse, the coroner’s courtroom, the doctor’s office and an inn. Hitchcock and Selznick were in agreement that Manderley was the co-star of the show.

Hitchcock knew how he wanted the great house to appear, and had several historic English mansions photographed, but Selznick didn’t like them. It was left to Wheeler to create the epitome of settings for Gothic romance, with a cavernous main hall, ornate rooms, gigantic fireplaces, towering staircases, high doors and massive chandeliers.

On September 1, 1939, the German Army invaded Poland. England declared war on September 3. Hitchcock and his predominantly British players were tormented by fears about their families and friends. On September 8, in an atmosphere of gloom and anxiety, principal photography of Rebecca commenced. Production was budgeted for 36 days, but in two weeks the company was five days behind schedule.

Hitchcock, who now championed Fontaine, spent a lot of time coaching her. Already lacking selfconfidence, she was particularly nervous because Olivier wanted to get rid of her. A product more of stage than screen, Olivier was driving both Hitchcock and Selznick to distraction with his habit of alternately slowing down action to make his role more showy, and then speaking very rapidly.

Hitchcock’s modus operandi of “cutting in the camera”— by pre-planning his shots meticulously and shooting no coverage from other angles — was especially galling to Selznick. This, he told the director, was the most important of the “things about your method of shooting which I think you simply must correct.”

Hitchcock was horrified when he learned that assistant director Eric Stacey and continuity supervisor Lydia Schiller were reporting to Selznick everything that happened on the set. He made their lives miserable for the duration.

Elaborate special photographic effects played an important role in getting Manderley onto the screen. According to the action and mood of the moment, it had to be perceived variously as warm and friendly, cold and forbidding, lively and in ruins. It would be shown by day, by night, in rain, mist and in flames. Hitchcock, Wheeler, production manager Ray Klune and special effects director Jack Cosgrove, ASC wanted to film the exteriors by utilizing large miniatures in two different scales. Matching portions of the exterior, such as the entrance, would be built full-scale. It was difficult to convince Selznick to use miniatures, because he feared that they would look fake. Hitchcock, a master at staging complex miniature scenes, was confident the method would work.

The first miniature of Manderley, the mansion with adjacent landscaping and a sky backing, almost filled a big, barnlike stage behind the administration building. A vestige of the silent films, the stage had never been soundproofed and was utilized mostly for special effects work. This model was used for close views, such as when a light is seen moving through the rooms and during the climactic fire, but there was not enough room on the stage to allow full shots of the building.

A second Manderley — half the size, but surrounded by forest and including the winding road through the woods — was built on another stage. There, Cosgrove filmed the superb visuals that open the film. The voiceover narration by the second Mrs. de Winter begins, “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. It seemed to me I stood by the iron gate leading to the drive, and for awhile I could not enter, for the way was barred to me. Then, like all dreamers, I was possessed of a sudden with supernatural powers and passed like a spirit through the barrier before me. The drive wound away in front of me, twisting and turning as it had always done, but as I advanced I was aware that a change had come upon it. Nature had come into its own again, and, little by little, had encroached upon the drive with long tenacious fingers. On and on wound the poor thread that had once been our drive, and finally there was Manderley — Manderley, secretive and silent as it had always been, shining in the moonlight of my dream…”

As the camera weaves through tangles, mists and gusts to reveal at last the ruins of the estate, the spectator is drawn quickly into the heart of the story. It is one of the great openings to a film of mystery, comparable to the discovery of the fort manned by dead soldiers in Beau Geste [see AC June ‘97).

The dream trip dissolves into a turbulent sea and cliffs, where de Winter and his soon-to-be-second wife meet for the first time. The scenery was filmed along the rocky northern California coastline near Carmel by a second unit helmed by D. Ross Lederman, a hard-working director of “B” mysteries and Westerns at Columbia and Warners, and veteran cinematographer Archie Stout, ASC. Fontaine and Olivier were doubled at the location for the long shots. Everyone in the unit was later subject to a three-day hospitalization for poison ivy infections.

The stars played several scenes with rear-projected Carmel footage. For one complex clifftop scene, they were placed in the middle distance of the landscape via a perfect split-screen shot composited by optical effects cinematographer Clarence W. D. Slifer, ASC in his lab on Stage Five. Other second-unit images from the Del Monte area provided backgrounds for scenes in the estate grounds. A third unit, under the supervision of Stacey and Lloyd Knechtel, ASC, filmed beach exteriors at Santa Catalina Island.

Using a new aerial-image printer he had designed with Don Musgrave and Oskar Jarosch, Slifer also composited numerous matte shots painted by Al Simpson. Slifer furnished Wheeler with 11” x 14” enlargements of the matted shots, upon which Wheeler or one of his staff sketched in the effects desired. The matte artist used these as guides; upper walls, ceilings and chandeliers were introduced into interiors, and architectural features were added to partial exterior sets. Some of the flames in the film’s climax were composited from shots made by Slifer during the burning of “Atlanta” in GWTW. A striking, muchemulated shot is a Danvers-eye-view of the burning ceiling crashing down.

Principal photography wrapped after 63 days on Monday, November 20 at 4 p.m., 26 days behind schedule. Three days were lost when Fontaine fell ill with influenza, followed by another three days due to a union “wildcat strike.” The last scenes were retakes of Rebecca’s burning bedroom, ending as the “R” on her nightgown case is devoured by flames. Selznick, who was constantly on the set to oversee every nuance, nixed the first staging for a variety of reasons; he felt that the room wasn’t clearly recognizable as Rebecca’s; that the lighting was unrealistic and not weird enough; that the “R” was not as meticulously placed as Danvers would have done it; that it was slow in catching fire; and that the flames failed to rise to create a “curtain of flames” for the end title.

With 216,000 feet of film to tinker with and a head full of ideas for new dialogue to be dubbed, Selznick took over. Some 30 scenes were scheduled for retakes. He borrowed German-born composer Franz Waxman from MGM, where he was finishing The Philadelphia Story, insisting that he compose the music while the picture was only roughly assembled and make it fit at the last moment. Most of the players were called back for dubbing sessions. Selznick was frustrated in his attempts to slow down Olivier’s clipped speech with dubbing.

Eventually, Waxman got to meld his fine score into the finished picture, building it upon a seductively erotic but somehow sinister melody reminiscent of his theme for Bride of Frankenstein. After Waxman left, Selznick removed his music for one sequence and substituted some Max Steiner music from A Star is Born, infuriating both composers.

With a final cost of $1,288,000, Rebecca emerged as a marvelous blending of Hitchcock inventiveness and Selznick opulence. Fontaine’s sensitive performance made her a major star overnight. Convincingly repressed and furtive during most of the film, she brings equal conviction to the later scenes in which she rises defiantly to her husband’s defense. Olivier earned wide acclaim for his strong portrayal of dignified but vulnerable nobility. Anderson, toning down her stage technique to the subtle needs of the camera, projects malevolence superbly. The other players, especially Sanders and Bates, are also memorable.

George Barnes’ cinematography is characteristically first-rate. Avoiding the use of extreme angles, short lenses and fantasy lighting — all stocks-in-trade of mystery melodrama — the cameraman’s work conveys mood largely through subtle shifts in lighting and composition.

“Well, it’s not a Hitchcock picture,” the director himself remarked in 1966 to Francois Truffaut, as quoted in the latter’s book Hitchcock. “The fact is, the story lacks humor.” Even so, Hitchcockian “touches” are abundant, and while there are no belly laughs, there are chuckles when George Sanders, Nigel Bruce, Gladys Cooper are onscreen. Audiences react audibly when the uncouth Van Hopper snuffs out her cigarette in a jar of cleansing cream. “Most girls would give their eyes to see Monte [Carlo],” she tells Max, who asks, “Wouldn’t that rather defeat the purpose?” The handling of Mrs. Danvers is pure Hitchcock: she is seldom shown moving, but suddenly appears in the frame when least expected — cold, unblinking, dressed in black, wearing an upswept hairdo that makes her look a bit top-heavy, cocking her head like a bird of prey. When she speaks of Rebecca, she seems to lapse into dementia.

Both the producer and director, jealous of each other’s trespasses, had misgivings about Rebecca. They needn’t have worried: following its gala premiere at Radio City Music Hall on March 28, 1940, it became a popular, critical and financial hit. It won the Academy Award as Best Picture of 1940 (besting Hitchcock’s own Foreign Correspondent, among other nominated films), brought an Oscar to Barnes (who had been nominated twice previously, and would be again twice after), and earned nominations for Olivier, Fontaine, Anderson, Hitchcock, Sherwood and Harrison, Wheeler, Kern, Waxman, Cosgrove and Arthur Johns (sound effects).

Even today, Rebecca is a hit show. As Hitchcock told Truffaut, “It has stood up quite well over the years. I don’t know why.”

CREDITS

The Selznick Studio presents its production of Daphne du Maurier’s celebrated novel; released through United Artists; produced by David O. Selznick; directed by Alfred Hitchcock; screenplay by Robert E. Sherwood and Joan Harrison;adaptation by Philip MacDonald and Michael Hogan; director of photography, George Barnes, ASC; music by Franz Waxman; music associate, Lou Forbes; art direction, Lyle Wheeler; special effects, Jack Cosgrove, ASC; interiors designed by Joseph B. Platt; interior decorations, Howard Bristol; supervising film editor, Hal C. Kern; associate film editor, James E. Newcom; scenario assistant, Barbara Keon; sound recording, Jack Noyes; assistant directors, Edmond Bernoudy, Eric Stacey and Ridgeway Callow; production manager, Ray Klune; second-unit directors, D. Ross Lederman, Eric Stacey; second-unit photography, Archie J. Stout, ASC, Lloyd Knechtel, ASC; casting test directors, John Cromwell, Anthony Mann; gowns, Irene; makeup artists, Monty Westmore, Ben Nye, Frank Westmore; hair stylist, Hazel Rogers; sound dubbing, Arthur Johns, Gordon E. Sawyer at Samuel Goldwyn Studio; optical effects, Clarence W.D. Slifer, ASC; matte artist, Albert Maxwell Simpson; executive assistant to producer, Marcello Rabwin; camera operators, Vincent Farrar, Arthur Arling, Irving Rosenberg; camera assistants, John F. Warren, Harry Wolf; technical advisor, W. A. Bagley; script supervisor, Lydia Schiller; script clerk, Adele Cannon; story editors, Kay Brown and Val Lewton; construction supervisor, Harold Fenton; still photographer, Fred Parrish; Western Electric recording. Running time, 130 minutes. Released May 12, 1940.

Maxim de Winter, Laurence Olivier; Mrs. de Winter, Joan Fontaine; Jack Favell, George Sanders; Mrs. Danvers, Judith Anderson; Beatrice Lacy, Gladys Cooper; Major Giles Lacy, Nigel Bruce; Frank Crawley, Reginald Denny; Colonel Julyan, C. Aubrey Smith; Coroner, Melville Cooper; Mrs. Van Hopper, Florence Bates; Dr. Baker, Leo G. Carroll; Frith, Edward Fielding; Robert, Philip Winter; Chalcraft, Forrester Harvey; Ben, Leonard Carey; Tabb, Lumsden Hare; Policeman, Billy Bevan; Chauffeur, Leyland Hodgson; Desk Clerk, Egon Brecher; Hotel Manager, Gino Corrado; Pedestrian, Alfred Hitchcock.

Parts of this article were based on conversations with the late Arthur Arling, ASC; Clarence W. D. Slifer, ASC; Lyle Wheeler; and Harry Wolf, ASC.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.