Why Renoir Favors Multiple-Camera, Long-Sustained-Take Technique

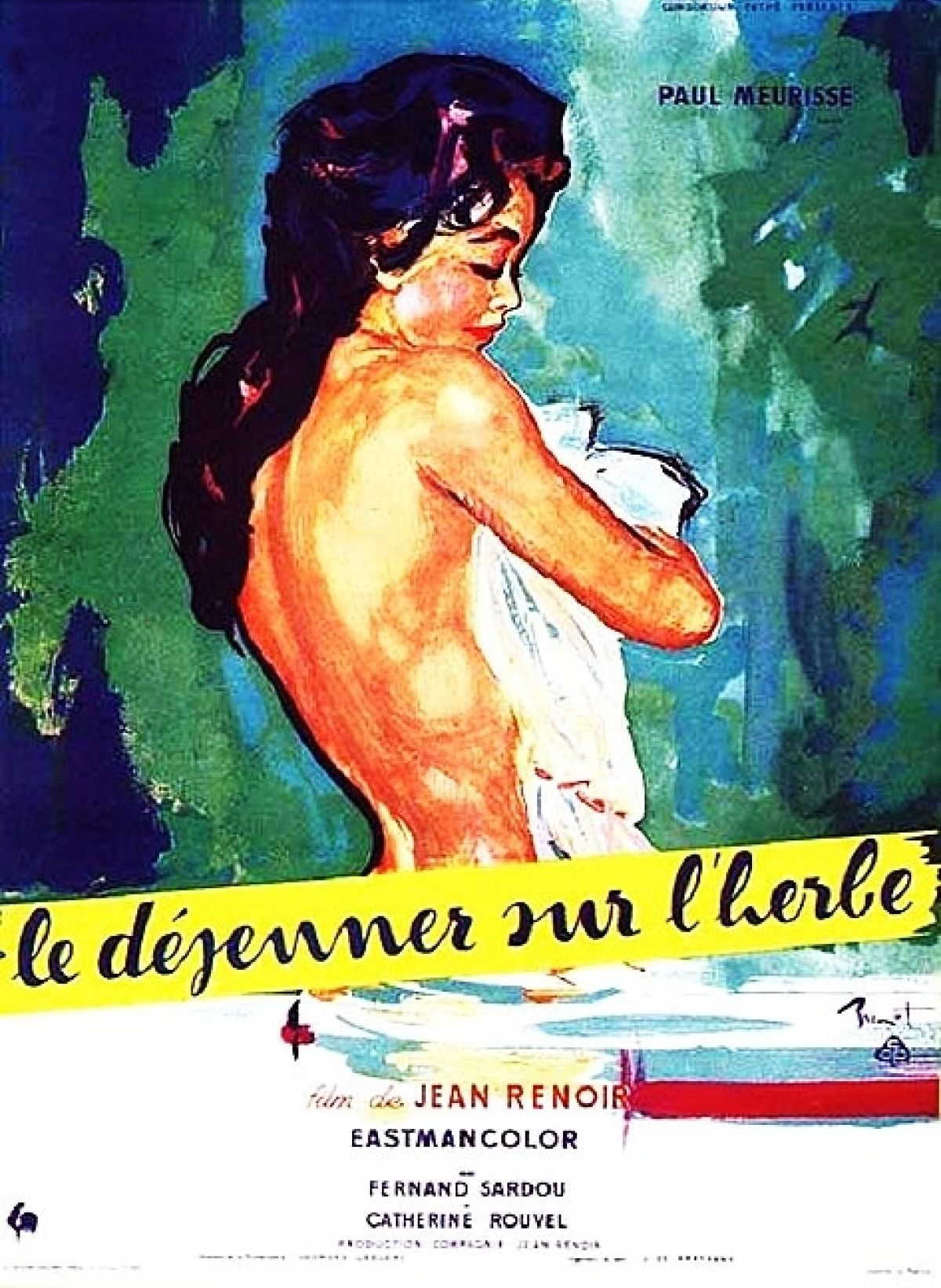

French director Jean Renoir’s camera techniques for 1959’s Picnic on the Grass.

This article was originally published in AC March 1960.

Few screen directors, perhaps, have so greatly influenced the cinematographic style of European film productions as has veteran Jean Renoir, whose most recent film Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (The Picnic Party, by which title I shall refer to hereafter) [Ed. Note: The film is now known as Picnic on the Grass] reveals interesting innovations in use of the camera that undoubtedly stem from Renoir’s recent excursions into program production for French television.

The more important of these innovations is best described as the not unfamiliar technique of employing several cameras operating simultaneously to record long sustained action and dialogue of players, as in TV. Renoir believes an actor is better able to develop a feel for his role and give a better reading when the action is not broken up into short takes for the sake of varying the camera angle or point of view. Using the sustained take technique, the action is photographed by several cameras, each shooting from a slightly different angle and with lenses of different focal lengths. This affords greater latitude for the director and the cutter to develop pace and build up suspense through the variety of “points of view” this method affords for each take.

In The Picnic Party, Renoir has perfected the methods he had employed earlier in his production Le Testament du Dr. Cordelier (Dr. Cordelier’s Will), which was made for both theatres and French television.

Renoir’s director of photography for both pictures was Georges Leclerc, who has several feature films and a number of short subjects to his credit, and who also was my cameraman on the production Tube On Tires, a short subject about the Paris subway produced in 1957. [See “Subway Filming Poses Problems In Lighting and Photography,” AC Dec. 1957.] More recently, Leclerc has been lighting programs for French TV.

The multiple-camera technique was used most ambitiously by Renoir in filming Le Testament du Dr. Cordelier (aka The Testament of Dr. Cordelier or Experiment in Evil, Renoir's adaptation of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde). Here several cameras were employed running continuously, or starting one after the other on cue as an actor progressed with a lengthy scene — as when exiting from a room, then proceeding along a passage, down a stair, etc — with each of the carefully placed cameras picking him up as he comes into view. This was a film with few actors, made in black-and-white, and in the conventional screen format.

The Picnic Party — a comedy about a famous biologist whose parthenogenetic doctrines are defeated by the love of a simple peasant girl — has a large cast, three-fourths of its scenes are natural exteriors, is in Eastman Color and 1.66:1 aspect ratio, and was photographed with the multiple-camera technique.

Mitchell cameras were chosen, not only because of their ruggedness and reliability, but because of the accuracy with which their lenses are mounted. The latter was a most important consideration because it insured smooth intercutting of negatives from all Mitchell cameras used in the multiple camera setup.

Still another factor which favored the Mitchells was the fact there is no glass in the camera’s matte box, which, as Leclerc pointed out, insured none of the differently positioned cameras would be bothered by glare and reflection when panning on a scene, regardless of position of the sun. This is a vexing problem with some European cameras.

In all, cinematographer Leclerc had at his disposal for this production a total of four Mitchells and one Cameflex — the versatile 400'-magazine-equipped French camera known in the U.S. as the Camerette. The latter was sometimes used with a blimp, thus providing a fifth sound camera when necessary. But its greatest value was as a portable, handheld camera for making roving shots. Leclerc’s camera crew numbered 12 in all: an operating cameraman and an assistant on each of the Mitchells; one cameraman for the Cameflex; plus two general assistants, one in charge of color problems and the other in charge of loading and care of the film magazines.

Renoir chose the 1.66:1 aspect ratio instead of the CinemaScope format because, if he likes to place his actors in groups, he does not want them too far apart. The 1:66:1 format also enabled Leclerc to use longer focal length lenses, which enabled him to reduce foreground and sky areas in scenes — factors which played no part in the human comedy aspects of the story Renoir was most interested in. Moreover, Renoir explained, the longer lenses made the actors more “present” on the screen. In this respect, TV imperatives and his own tastes were in agreement.

Before actual shooting of the picture was begun, Renoir journeyed to the location where most of the action was to be filmed — les Colettes, the old country house of his father, Auguste Renoir, famous French impressionist painter. It stands near Gagnes, a picturesque village on the French Riviera. To facilitate construction at the studio of the necessary interior sets, accurate measurements were taken of the rooms of the historic country house. While set construction progressed, extensive rehearsals were conducted involving all technicians, cameras, lighting and sound equipment, as well as the actors. All this was important, of course, in order to insure the flawless performances and the technical excellence of the photography in filming the action in sustained, unbroken continuity using several cameras as previously described.

Nearly four-fifths of this 100-minute production was shot at, or near, les Colettes. The weather was generally good. However, because the location was close to the Mediterranean, distant backgrounds in long-shots were marked by haze. The beautiful trees and meadows surrounding the old country house enhanced the pastoral effect so desirable for the exterior action of the picture. To achieve the light colors and soft photography which Renoir felt these scenes demanded, Leclerc consistently used 85/N3 and 85/N6 filters on his camera lenses so that in the bright Riviera sun he could work at stops of f/3.5 or f/3.2.

Comparatively few booster lights were used — just one 225-amp. and three 150-amp. lamps were brought to the location along with two small generators. The sound engineer (Joseph de Bretagne) mounted a separate mic at each camera location so that he often had as many as five channels to take care of at one time. The electricians worked in two crews — one setting up the lights in advance and the other working during the filming. Though the picture, including the Paris studio interiors, was shot in three weeks, it was not for financial reasons that Renoir chose the methods that he did and which resulted in completing the picture in such a short period of time. To him the actors are all-important, and by filming action in long, sustained takes he was able to obtain from his cast performances having more human warmth and spontaneity than when the conventional “short-take” method is employed.

There were some exceptions, of course: in one scene in which an old shepherd produces a momentary hurricane simply by sounding a few notes on his flute, the noise made by the wind machines made silent filming imperative, and the required sound was dubbed in later—something that Renoir, a stickler for authenticity in scenes and action, hates.

There were problems in makeup, too. Most of the actors were sensitive to the sun and as days went on, their skins became more sunburned. This required a very careful check of the principal players each day by cinematographer Leclerc so that there would be no visible change in the color tones of faces from day to day day—a matter that was remedied by progressively changing the type of makeup applied daily to these players.

What made the problem of face lighting more intricate, Leclerc explained, was that much of the exterior action was played under or near trees in which the actors invariably moved from shade to sunshine or vice versa. Also, with continuous filming of scenes with five different cameras at various positions, the players sometimes did not face the camera. Here, cinematographer Leclerc’s wide experience in photographing documentary films served Renoir's preferences. In documentary films, Leclerc explained, the people on the screen appear working or enjoying themselves without troubling to be “correctly” positioned for the camera. It is this style that marks the photography of The Picnic Party, and which, according to Renoir, enhances the impression of realism — “makes you break into the real world of people who are concerned with their own lives, not into the world of actors playing to the theatre audience.”

An interesting footnote to this account of the photography of The Picnic Party is the fact that nearly every scene was done in a single take — eloquent testimony of what can be accomplished when a director with ideas and an imaginative cinematographer work harmoniously together to weld the dramatic with the pictorial for an outstanding screen result.

Access every issue of AC and every story from more than 100 years of coverage with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.