Flashbacks: AC In the ’60s

American Cinematographer’s coverage during the 1960s reflects adventurous, evolving approaches to filmmaking.

blew minds in the late 1960s.

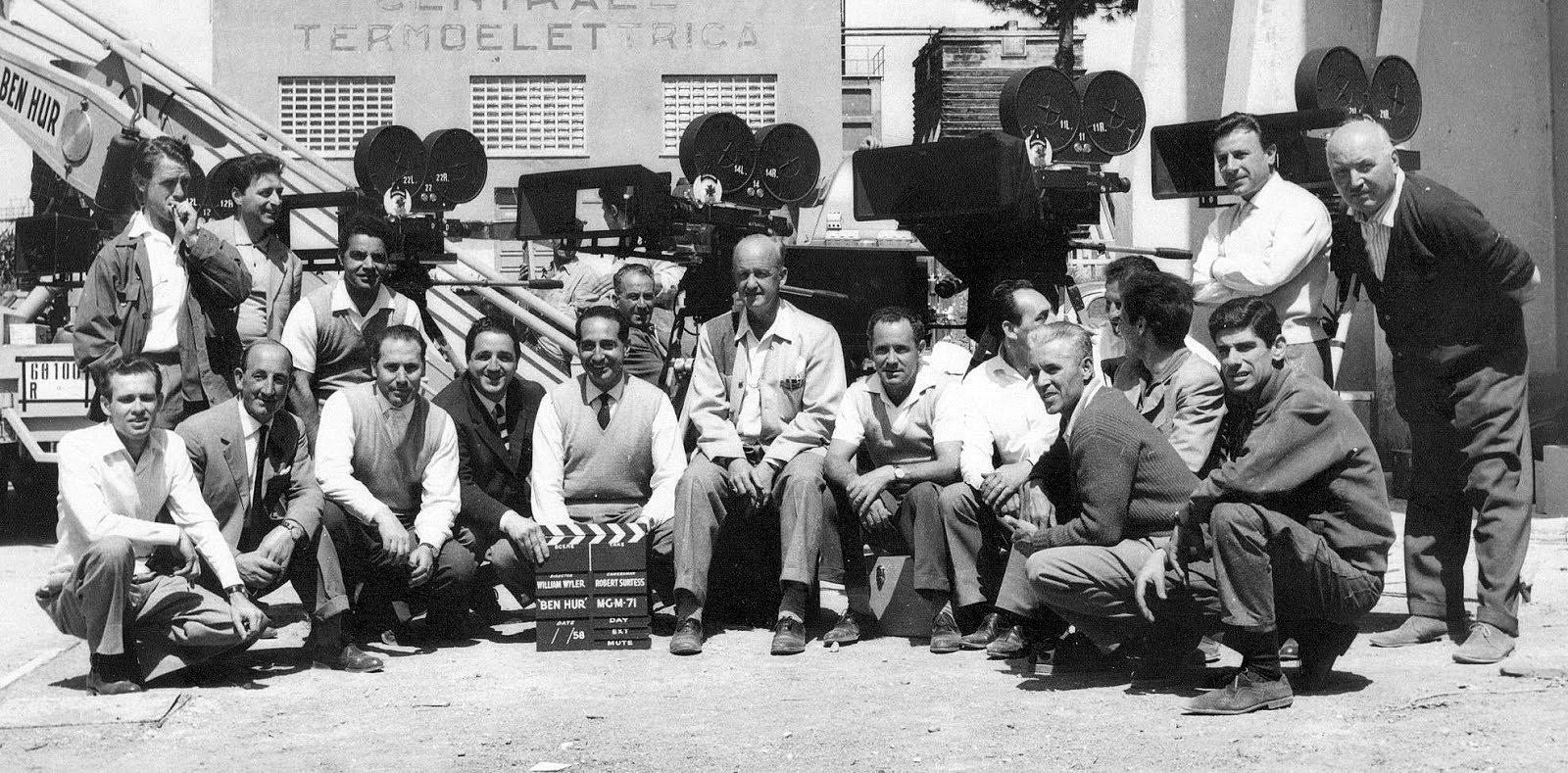

When the 1960s began, American Cinematographer was still showcasing certain productions that had a whiff of the 1950s: novelty projects like Scent of Mystery, filmed in glorious “Smell-O-Vision” (which could deliver 30 different odors to individual seats via perforated cylinders mounted just in back of and below the armrests), and widescreen epics like Ben-Hur, which the magazine covered in February 1960 (focusing on the movie’s thrilling 65mm chariot race, a sequence described as “not just a race, but a race to the death” involving 6,000 extras, elaborate stunts and 82 horses “obtained in Yugoslavia”).

covered in the February 1960 issue of AC. The production’s crew (below, Surtees at center) captured

elaborate and complex stunts for the movie’s thrilling chariot race.

But as the decade progressed, the magazine began shifting its focus to other types of productions, techniques and new equipment that would mark the ’60s as an era of forward-thinking artistry, experimentation and cutting-edge filmmaking.

The March 1960 issue began paving the way with a feature titled “Why Renoir Favors Multiple Camera, Long Sustained Take Technique,” which explained how famed director-producer Jean Renoir had been adapting methods he’d used for French TV productions to his work on cinema projects like his then-most-recent feature, Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (Picnic on the Grass). The most important of these innovations, the article submits, is “the not unfamiliar technique of employing several cameras operating simultaneously to record long, sustained action and dialogue of players, as in TV. Renoir believes an actor is better able to develop a feel for his role and give a better reading when the action is not broken up into short takes for the sake of varying the camera angle or point of view. Using the sustained-take technique, the action is photographed by several cameras, each shooting from a slightly different angle and with lenses of different focal lengths. This affords greater latitude for the director and the cutter to develop pace and build up suspense through the variety of ‘points of view’ this method affords for each take.”

Renoir’s director of photography on the picture was Georges Leclerc, who had several feature films and a number of short subjects to his credit, and who had also been lighting programs for French TV. In France, the Nouvelle Vague (New Wave) movement was already underway, with its rejection of more traditional filmmaking methods and an embrace of experimentation in cinematography, editing, and storytelling methods in general.

Another cinematographer of European renown, future ASC member Sven Nykvist, penned an article titled “Photographing the Films of Ingmar Bergman” for the October 1962 issue of AC. In it, he touts the creative benefits of the new, fast black-and-white emulsions he’d been using on The Silence: “When Bergman handed me the script, he explained the dream effect he wanted: ‘There must not be any of the old, hackneyed dream effects, such as visions in soft focus or dissolves. The film itself must have the character of a dream.’

“Bergman believes in photography having high contrast, so my preparations for this dream effect began with a series of experiments with different kinds of film emulsions. We were surprised to discover the strong graininess effect we obtained from our experiments with 16mm Ektachrome Commercial blown up to 35mm black-and-white. We also made photographic tests with ordinary sound recording film and with orthochromatic emulsions, and all these tests included the films of various manufacturers.

“The conclusion reached through the tests was that each film and each laboratory method employed offered some of the advantages we sought. Our final decision was to shoot with Eastman Double-X negative and develop it to a higher than normal gamma.”

The influence of European cinema is also apparent in the magazine’s April 1960 coverage of Federico Fellini’s masterpiece La Dolce Vita, photographed by Otello Martelli, who had previously shot La Strada and Nights of Cabiria for the Italian director. In a piece titled “Filming La Dolce Vita in Black-and-White and Widescreen,” author Libero Grandi writes, “Foregoing many of the established photographic rules, Martelli expresses in a key-tone all the various characters and events taking place in the film itself. His choice of lenses is often unique, too. Martelli used 75mm, 100mm and 150mm long-focus lenses for close-ups and two-shots in place of the 50mm lens generally used for making similar shots in CinemaScope.”

Analyzing the psychology of the duo’s approach, the article observes, “Where there are shots with dialogue between two actors (one in C.U. and the other in the foreground) the depth of field is quite limited because of the long-focus lenses used; the focusing operation (during shooting) had to follow each actor in turn very carefully, throwing out of focus the actor who had just finished speaking and bringing the other into sharp focus. An example is the dialogue scene between Steiner and Marcello at Steiner’s house — the technique underscores their hopeless isolation.

“The hazy background against which the actors play the sequence further points up their solitude — their incapability of reaching a common ground. Remarking on this, Martelli said: ‘Director Fellini has given the film individual style by deliberately distorting the characters and their surroundings, and also by their clear-cut figures.’”

The magazine’s embrace of international production also took flight — quite literally — with the appointment of the globetrotting Herb A. Lightman as editor. Lightman assumed the reins for one issue, in February 1965, after the passing of Arthur E. Gavin (who held the post from July 1948 to January 1965), before ceding the position to Will Lane (who edited one issue in March 1965) and then Don C. Hoefler (who served as editor from April 1965 to January 1966). The editorial baton passed back to Lightman in February 1966, and he held the position until June 1982; along the way, he became well known for visiting sets on location all over the world.

shot by Erich Kullmar.

American Cinematographer additionally paid editorial attention to striking independent productions, experimental cinema and even student filmmaking during the ’60s. The August 1961 issue had a full feature on the iconic indie picture Shadows, directed by John Cassavetes and shot by Erich Kullmar. Featuring a jazz score and a highly improvisational, freeform approach, the picture came to epitomize the concept of “rebel filmmaking.” Referencing a previous AC piece titled “The Experimental Film” (AC Jan. ’61), the Shadows article begins by stating, “While such cinematic sorties are rarely commercial successes, they nevertheless are valuable contributions in filmmaking in that many are possible trail-blazers to fresher, more vital motion-picture techniques. Shadows, the initial directorial effort of actor John Cassavetes, is a phenomenon among experimental films in that, despite the fact it was never intended for theatrical release, it nevertheless is currently enjoying a successful run on the art film circuit.”

Noting that Shadows had earned several international awards (including the 1960 Venice Film Critics Award) and praise from New York Times critic Bosley Crowther, the article concedes that the movie might not be for all tastes, while citing some of its cinematic antecedents: “Other critics have managed to contain their enthusiasm, pointing out that the film’s narrative frequently rambles in confused and tedious circles, and that the technical quality of sound and photography ‘leaves much to be desired.’ The controversy reaches a peak in regard to the basic premise of the film’s approach — that of improvisation. Detractors point out that the device of improvisation is anything but new, having long been the mainstay of home-movies, as well as of Roberto Rossellini, who used it with stunning impact in Open City and with considerably less success in Paisan and several subsequent efforts. Such critics are not at all certain that the art of the cinema is exalted by allowing actors to make up the plot and dialogue as they go along.”

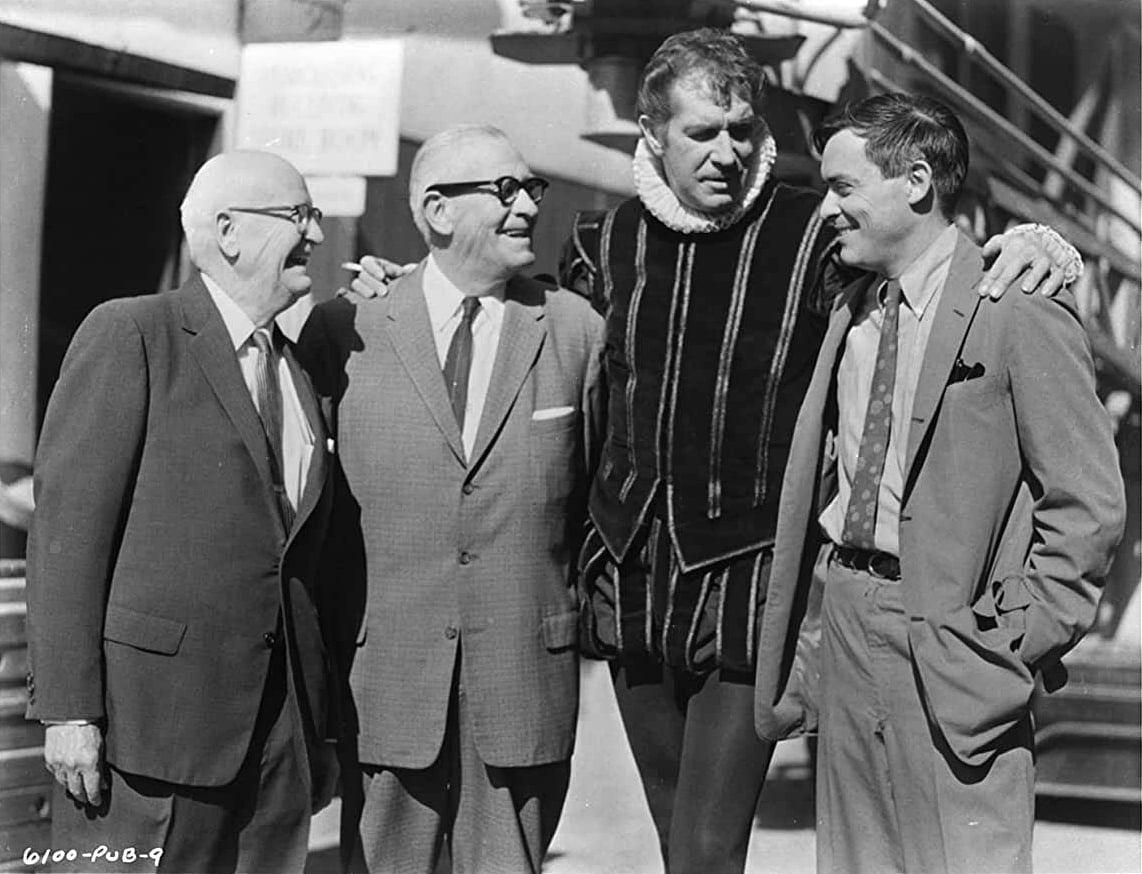

In October 1961, the magazine threw a spotlight on other indie strategies with coverage of The Pit and the Pendulum, a horror film from American International Pictures shot by ASC member Floyd Crosby for director-producer Roger Corman, who became legendary for his thrifty, low-budget approach to cinema. In a possible affront to leading man Vincent Price, the text notes, “Except for the absence of big-name stars in the cast, the film boasts production values comparable to pictures costing five times as much.”

A hands-on approach to student filmmaking was praised in the April 1966 article “Film Production by Cinema Students at UCLA,” which proposes, “Unorthodox teaching methods, including actual film production by students, prove effective in imparting cinematic skills.” Considering that UCLA alumni from the ’60s include ASC members Stephen H. Burum and Dean Cundey and directors Carroll Ballard, Charles Burnett and Francis Ford Coppola, the school may have been onto something by letting students actually handle equipment.

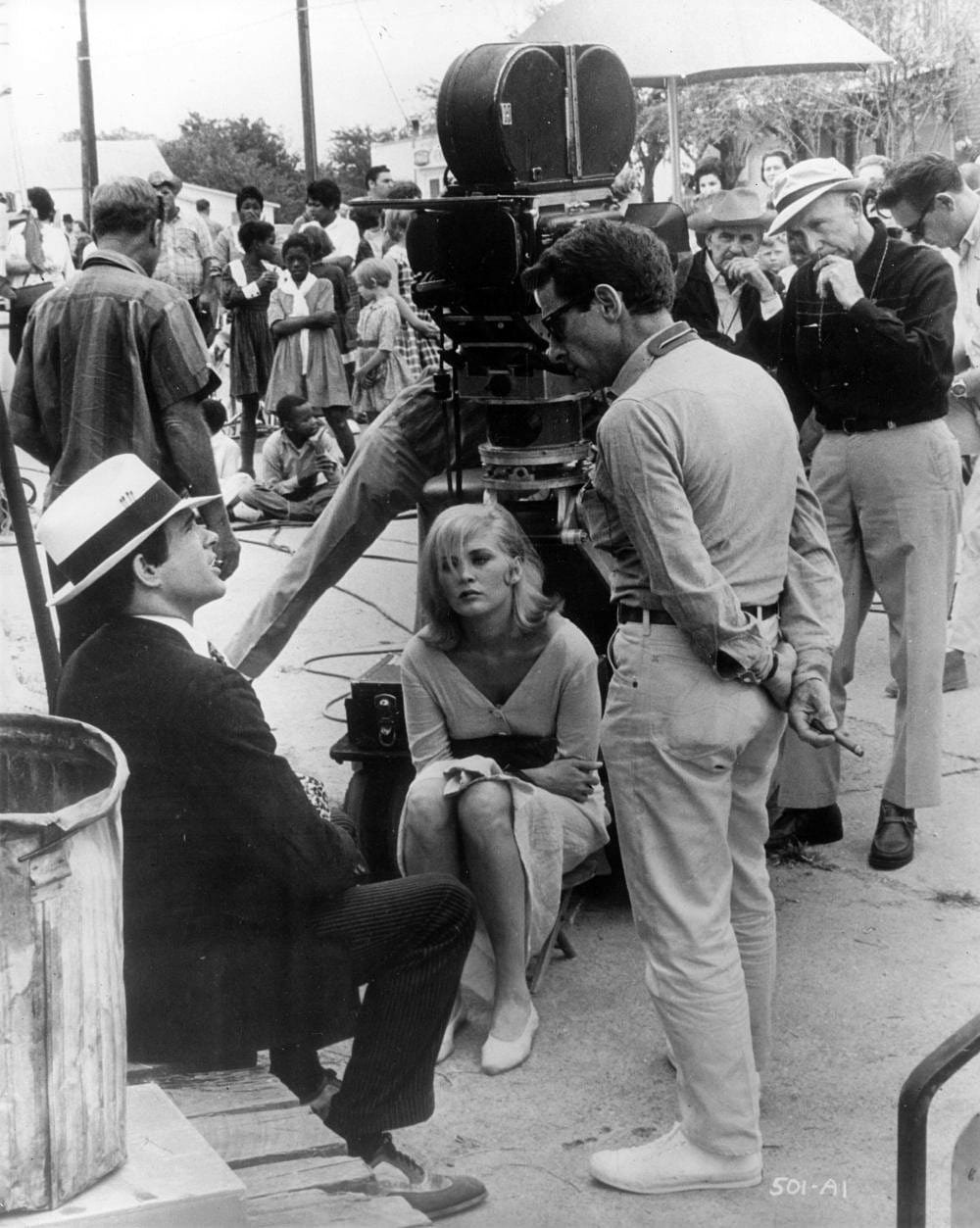

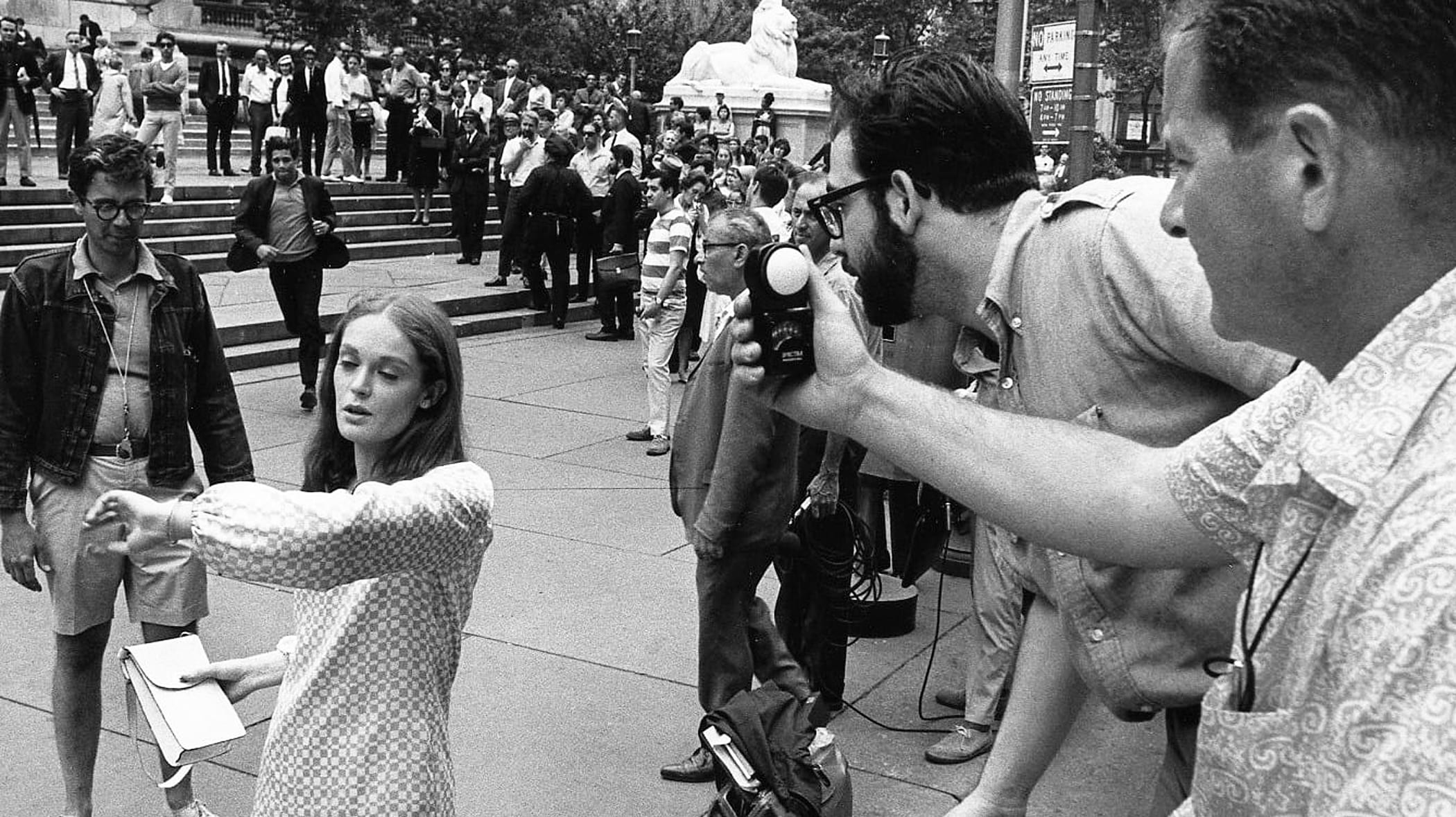

One of Coppola’s earliest directorial efforts was covered in June 1967 with the appropriately titled article “The Far-Out Photography of You’re a Big Boy Now,” which describes the film, shot by ASC member Andrew Laszlo, as “a pinch of Nouvelle Vague, a pinch of cinéma verité and a heap of good, solid professional know-how.”

Cinéma-verité techniques were advocated for cinematographers seeking new modes of expression in articles like “Cinéma Verité and the Documentary Film” (AC Oct. ’68) and “The Truth About Cinéma Verité” (AC May ’69), and select verité production strategies were eventually adopted by trailblazing feature cinematographers as well. In his October 1968 piece, author Mike Waddell explains, “The method makes use of the almost unlimited flexibility of the new 16mm self-blimped cameras; the easily-portable, high-quality sound recording equipment; the high-intensity, light-weight lighting equipment; and the new high-speed black-and-white and color film stocks that are running a close second in quality to the slower emulsions we have been used to. The flexibility and freedom permitted by these improved cameras, recorders, lights and film emulsions naturally gave rise to more sound shooting on location and especially more first-hand coverage of events as they happened. The cameraman discovered that by being able to be on the scene and not be restricted by heavy, hard-to-move equipment, he was able to photograph the scene differently from the way he had in the past. He was able to capture those spontaneous occurrences of the moment.”

However, Waddell cautions, “Being new and different in your film approach can be an asset if your innovations are born out of a need for better communication. But no technique you employ should jump out at the audience as something that is ‘new and different.’ If a technique calls attention to itself, it is bad because it will divert the audience’s attention from what you are attempting to say.”

member Linwood

Dunn’s special effects for the enduring sci-fi series Star

Trek in the October

1967 issue.

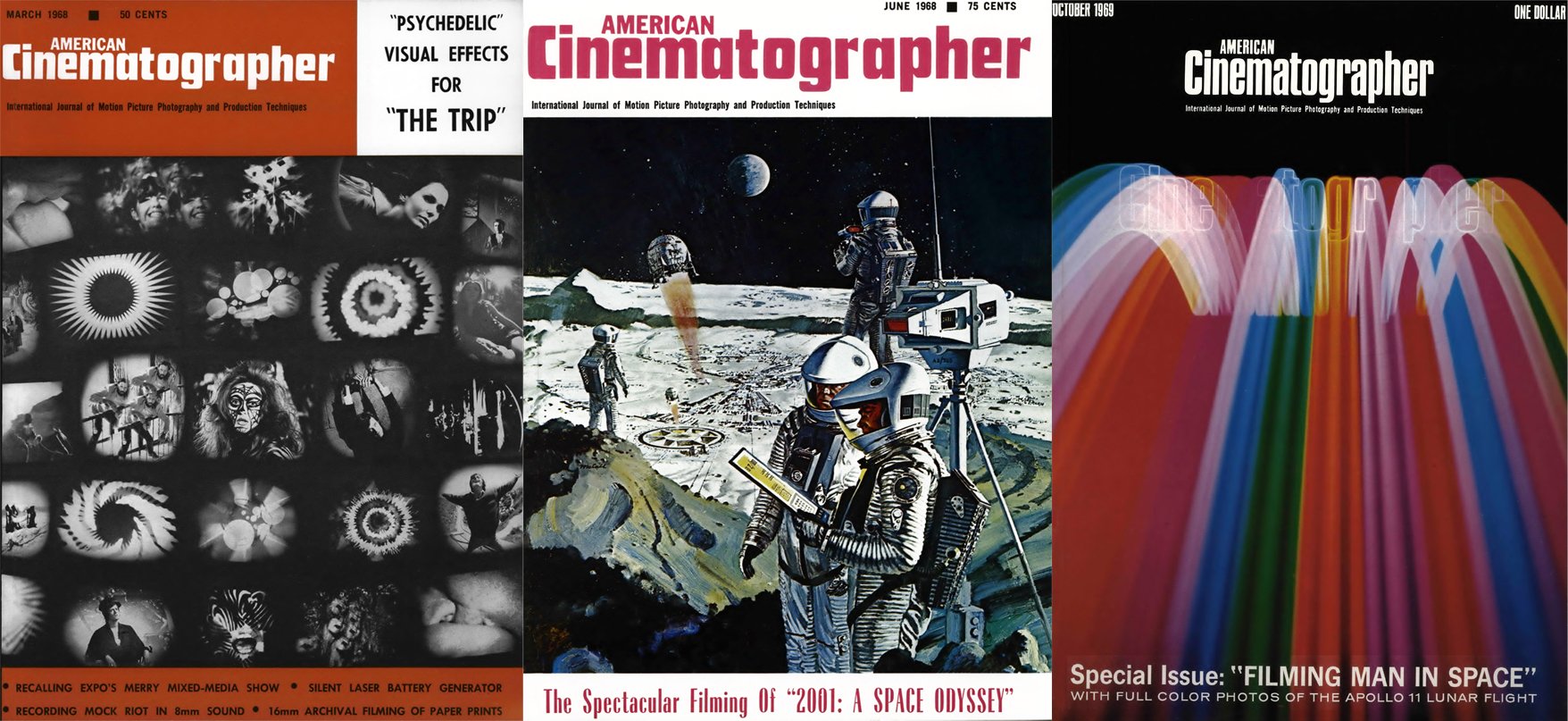

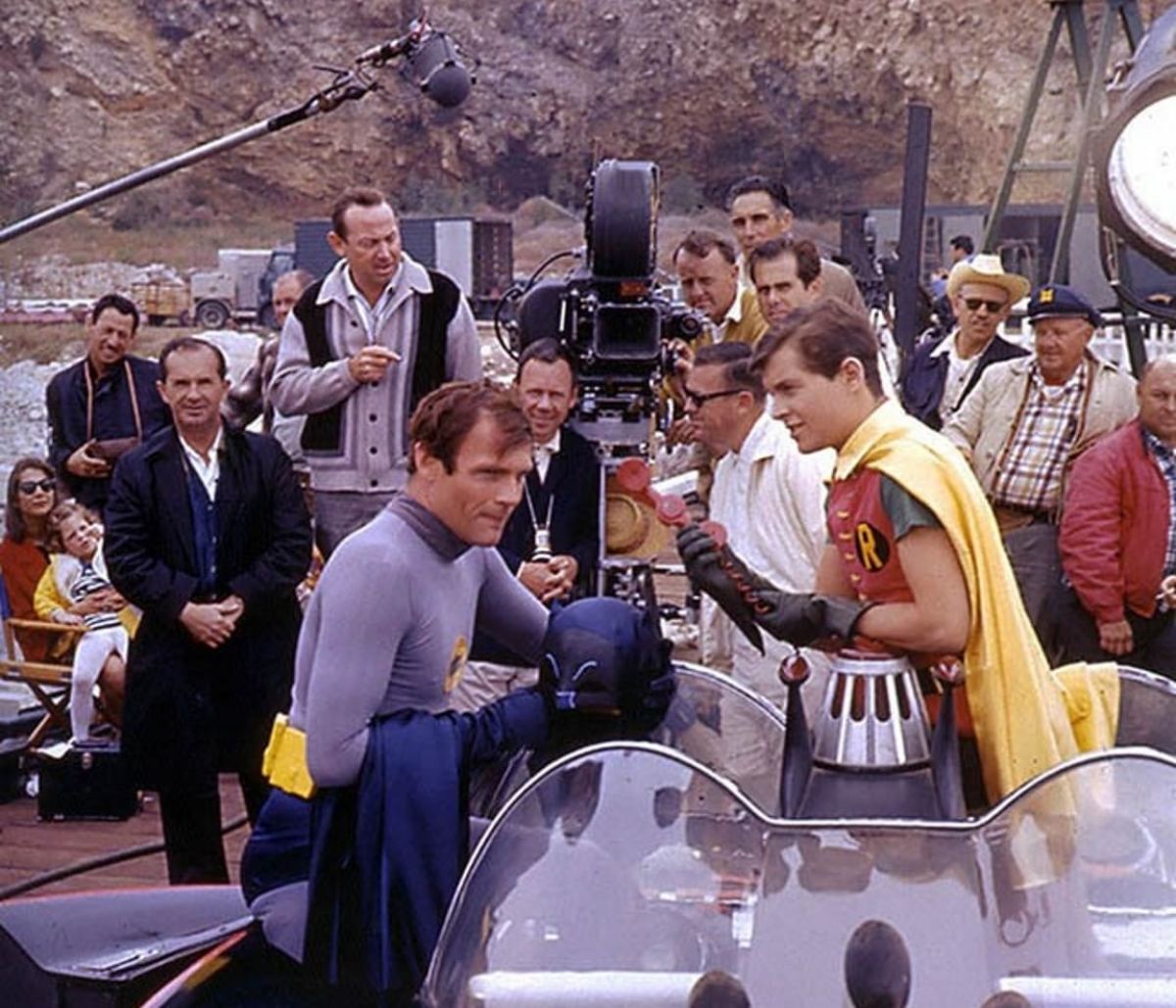

The magazine’s range during the 1960s spanned from popular genre productions like Star Trek (AC Oct. ’67), Batman (AC June ’66) and Planet of the Apes (AC April ’68) to more high-minded world-cinema fare like The Battle of Algiers (AC April ’67), Ryan’s Daughter (AC Aug. ’69) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (covered with three in-depth articles in June 1968). Its pages regularly touted the appearance of new, forward-thinking tools and techniques in articles such as “Mitchell Introduces New 35mm Reflex Camera” (AC June ’60), “Electronic Film Editing” (AC Dec. ’62), “Pixillation — New Technique with Commercial Possibilities” (AC July ’62), “Zoom Lens Technique” (AC Jan. ’63), “ColorTran’s Electronic Dimmer System” and “Function of Dimmers in Set Lighting” (AC July ’63 and Aug. ’64, respectively) and “The Camera of the Future” (a June 1966 article promising the advent of “a compact miniaturized reflex camera that will include highly efficient binary, through-the-lens exposure control”).

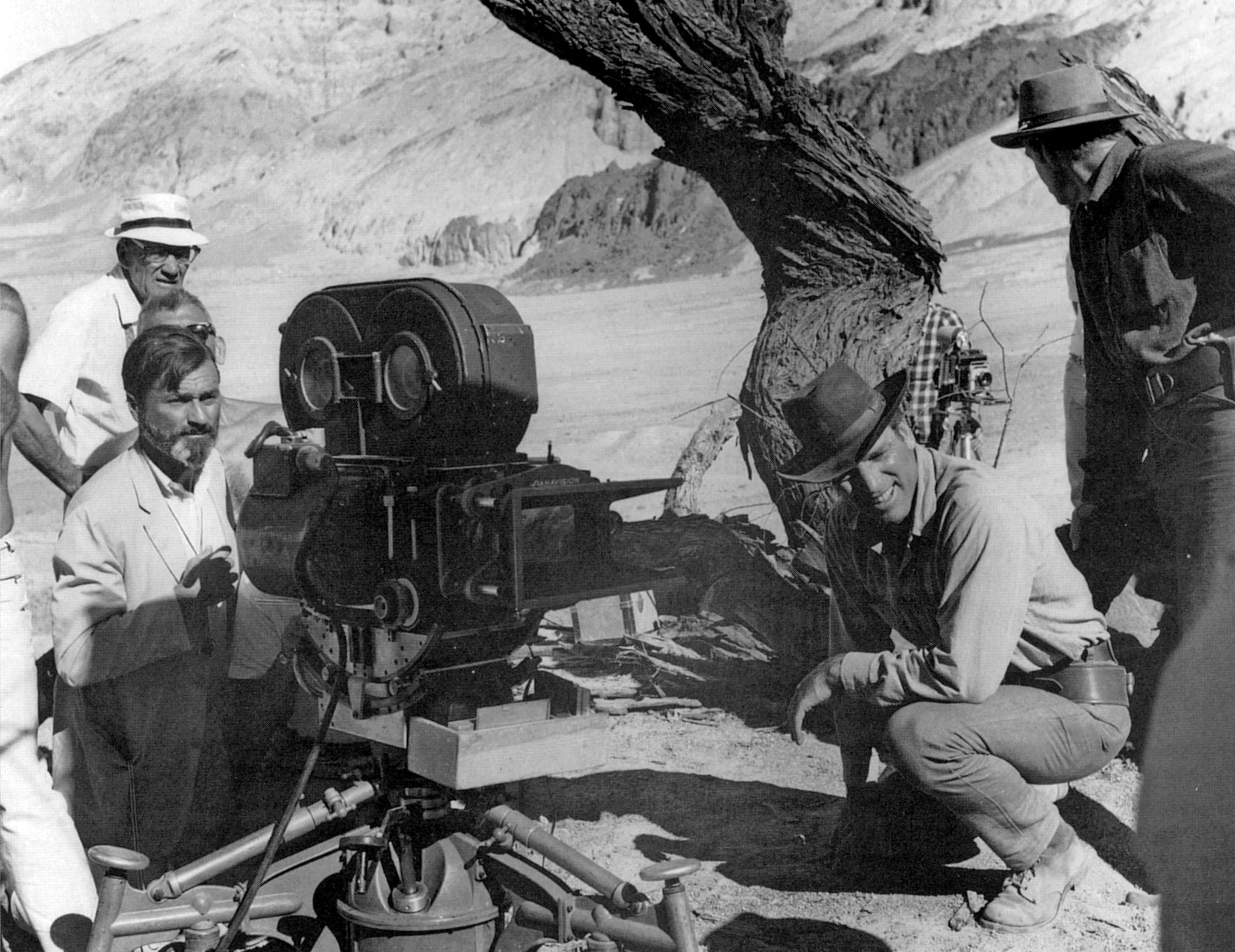

The work of American cinematographers who became iconic ASC members was covered throughout this era, and they had plenty to say via new and exciting methods. Sixties issues of AC offer coverage of movies shot by Burnett Guffey, Conrad L. Hall, Gerald Hirschfeld, Winton C. Hoch, James Wong Howe, Richard H. Kline, Charles B. Lang, Philip Lathrop, Ted McCord, Harry Stradling Sr., Robert Surtees and Haskell Wexler — including Bonnie and Clyde, The Professionals, Hud, The Boston Strangler, Charade, The Cincinnati Kid, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, The Thomas Crown Affair, The Graduate, and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

ASC members were behind some of the decade’s most interesting and innovative films:

The magazine occasionally sought out commentary from top directors as well, scoring interviews with Alfred Hitchcock (AC May ’67) and Stanley Kubrick (AC June ’68), among others.

Other articles serve as time-stamps of the era. The Vietnam War was addressed in the September 1968 issue with a pair of articles — one about the actual war as filmed by U.S. Air Force cameramen, and another about production of the feature The Green Berets. If the war wasn’t surreal enough, the magazine also published a piece titled “Creating the ‘Psychedelic’ Visual Effects for The Trip” (AC March ’68), which details “the skilled application of intricate ‘light show’ and optical technology” to simulate “the far-out hallucinations induced by LSD.”

The magazine’s open-minded approach during the 1960s is possibly best summarized by two paragraphs from that January 1961 article on “The Experimental Film,” which endorse a spirit of adventurous creativity that can still serve to inspire today’s cinematographers:

“The use of the motion-picture camera as a creative instrument is something else again, for this is a skill that cannot be learned through books and lectures. There are only two ways to really learn anything about it: first, by viewing and analyzing outstanding films of all types — and, secondly, by plunging in and actually making films. Because the experimental film places virtually no restrictions upon the creativity of the serious student of cinema, it can function as a valuable, even necessary, training ground for the aspiring cinematographer. Nor is it the novice alone who can benefit from observing and working with this type of film. Many an established cameraman, bogged down in a rut of tried-and-true conventional technique, can infuse new life into his work by allowing his camera to take off on an occasional flight of experimental fancy — on his own time, of course.

“The important point is that one is frankly and openly trying out techniques. The very word ‘experiment’ implies a searching in which failure is, if anything, more likely than success. For this reason, the experimentalist should not be chagrined or even surprised if many of the effects he attempts do not quite come off. On the contrary, in working with film it is often possible to learn more from a failure or near-miss than from an out-and-out success.”

Throughout the 1960s, American Cinematographer paid close attention to the Space Age — specifically, progress by NASA that culminated in the awe-inducing, decade-capping imagery captured by the Apollo 11 astronauts during their moon landing on July 20, 1969.

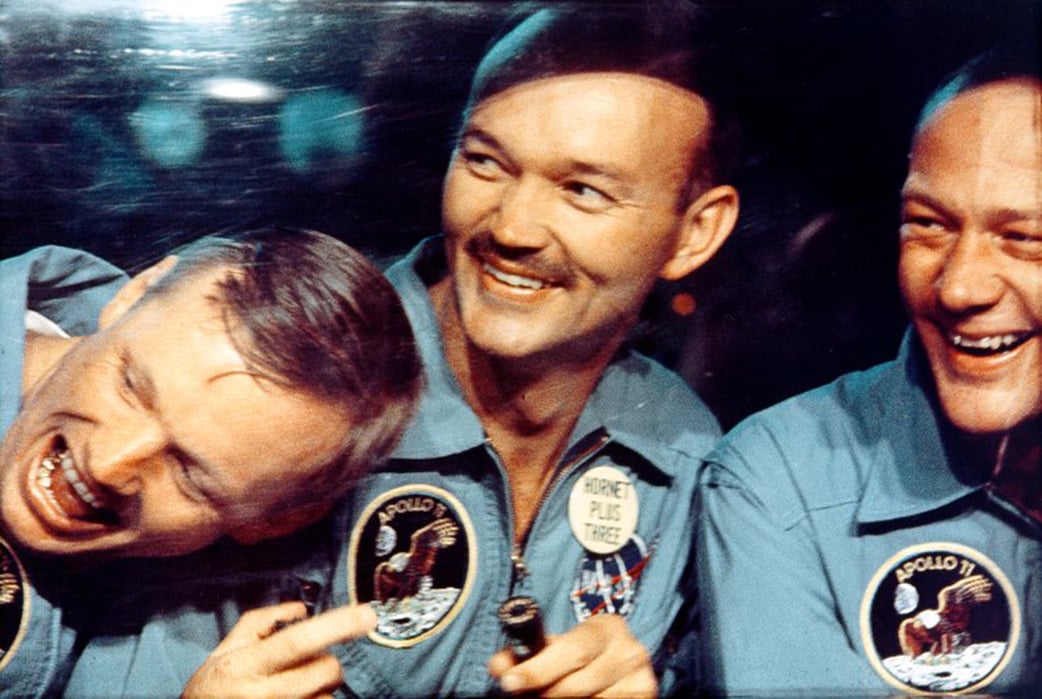

In October of that year, AC honored this achievement by dedicating a special issue to the accomplishments of Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins. The ASC itself went “one small step” further by electing all three astronauts to honorary Society membership — an event chronicled in the November 1969 issue of the magazine.

Earth, the astronauts — Neil

Armstrong, Michael Collins

and Buzz Aldrin — were

made honorary members of

the ASC.

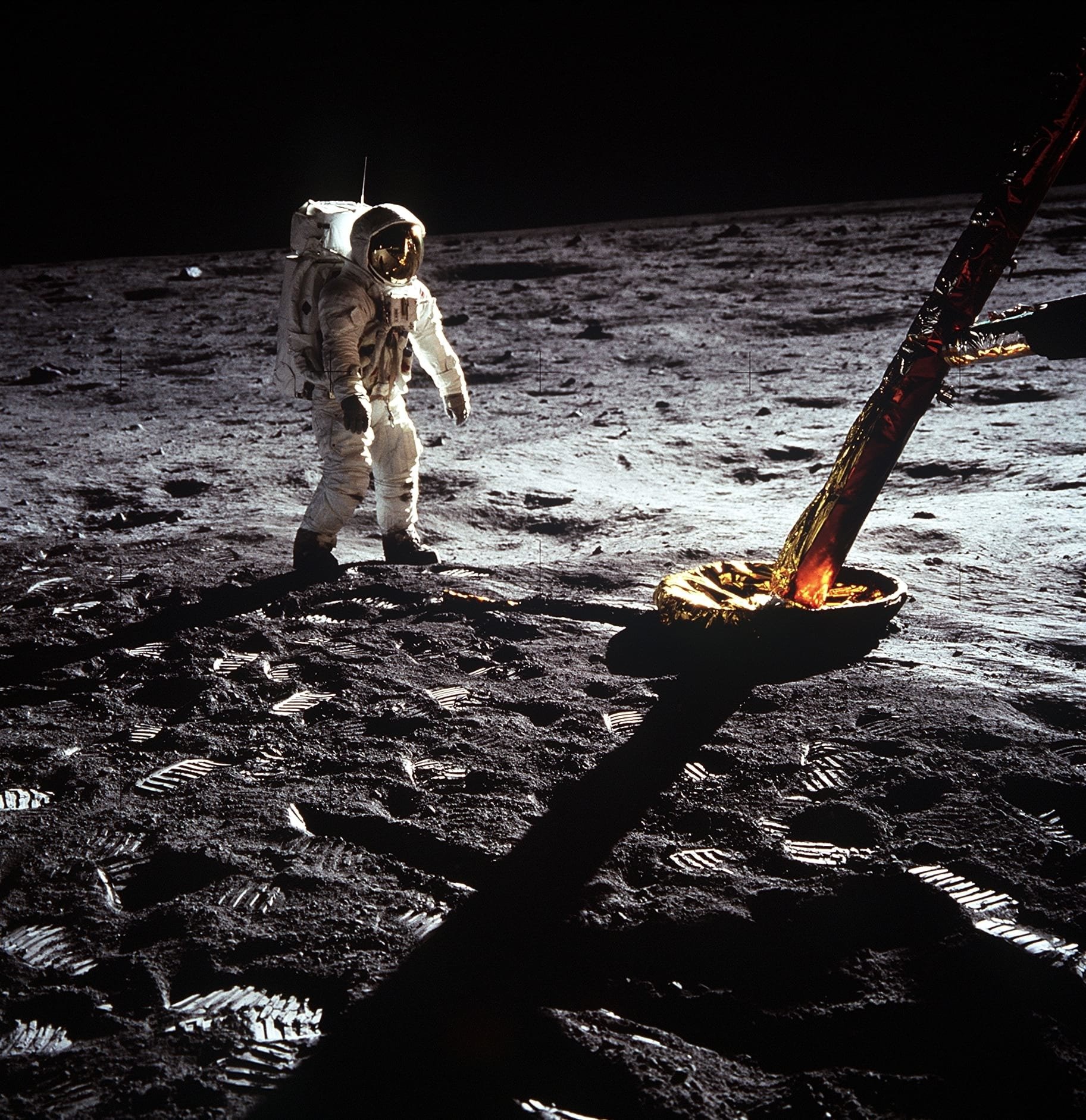

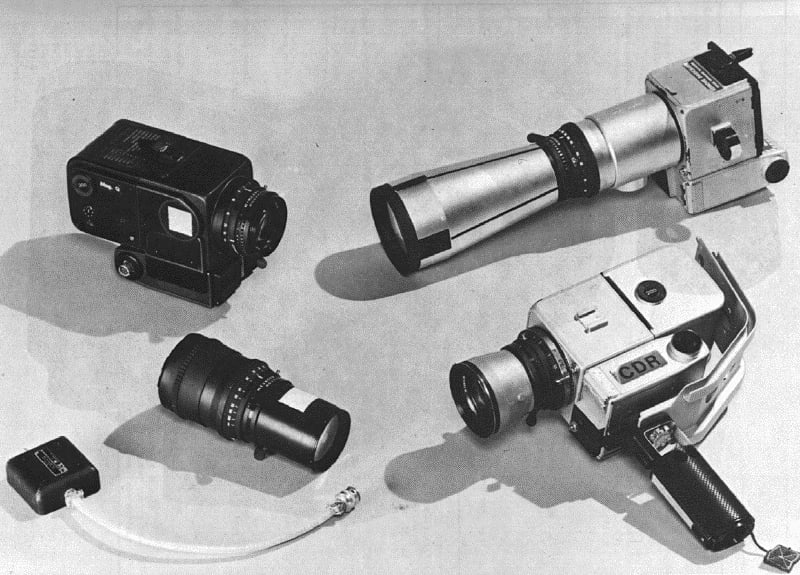

As that announcement proclaimed, “Though not professional photographers, they have given the world a priceless and unique photographic record of an epic journey. They have photographed sights never before personally seen by the eye of Man and are the first to have done so on a celestial body other than Earth itself. Moreover, in operating the specially adapted Hasselblad still cameras and the custom-designed Maurer motion-picture camera, which recorded the Apollo 11 lunar flight and moon landing, they have become pioneers in the use of these exotic camera configurations. Even the estar-based film emulsions which they employed represent a significant advance in the development of sensitized materials.”

Lauding the “high degree of artistry, sensitivity and flair” the astronauts brought to their photography, the magazine added, “It must be remembered, also, that this historic photographic achievement was accomplished under conditions never before encountered by human beings. Moving about in their cumbersome space suits in a gravity only one-sixth that of Earth, preoccupied by the series of technical chores and experiments which they were charged to carry out, they still managed to make these extraordinary pictures.”

In the years leading up to the moon landing, AC reported diligently, and at regular intervals, on “out of this world” cinematography, in articles such as “The Space Age — New Challenge for Cinematography” (AC May ’60), “Films to Train Space Ship Pilots” (AC Aug. ’61), “Role of Cinematography at Cape Canaveral” (AC Nov. ’62), “Space Cameras Ride a Missile” (AC Feb. ’63), “Filming With Surveyor I On the Moon” (AC Aug. ’66), “How Technology from the Moon Advances Earth Photography” (AC Jan. ’67) and “How Cinematography Is Used to Monitor Apollo 4 Moon Shot” (AC Nov. ’67). The magazine even published comments by Ray Bradbury after the renowned sci-fi author addressed the ASC membership (“Ray Bradbury Speaks On ‘Film in the Space Age,’” AC Jan. ’67).

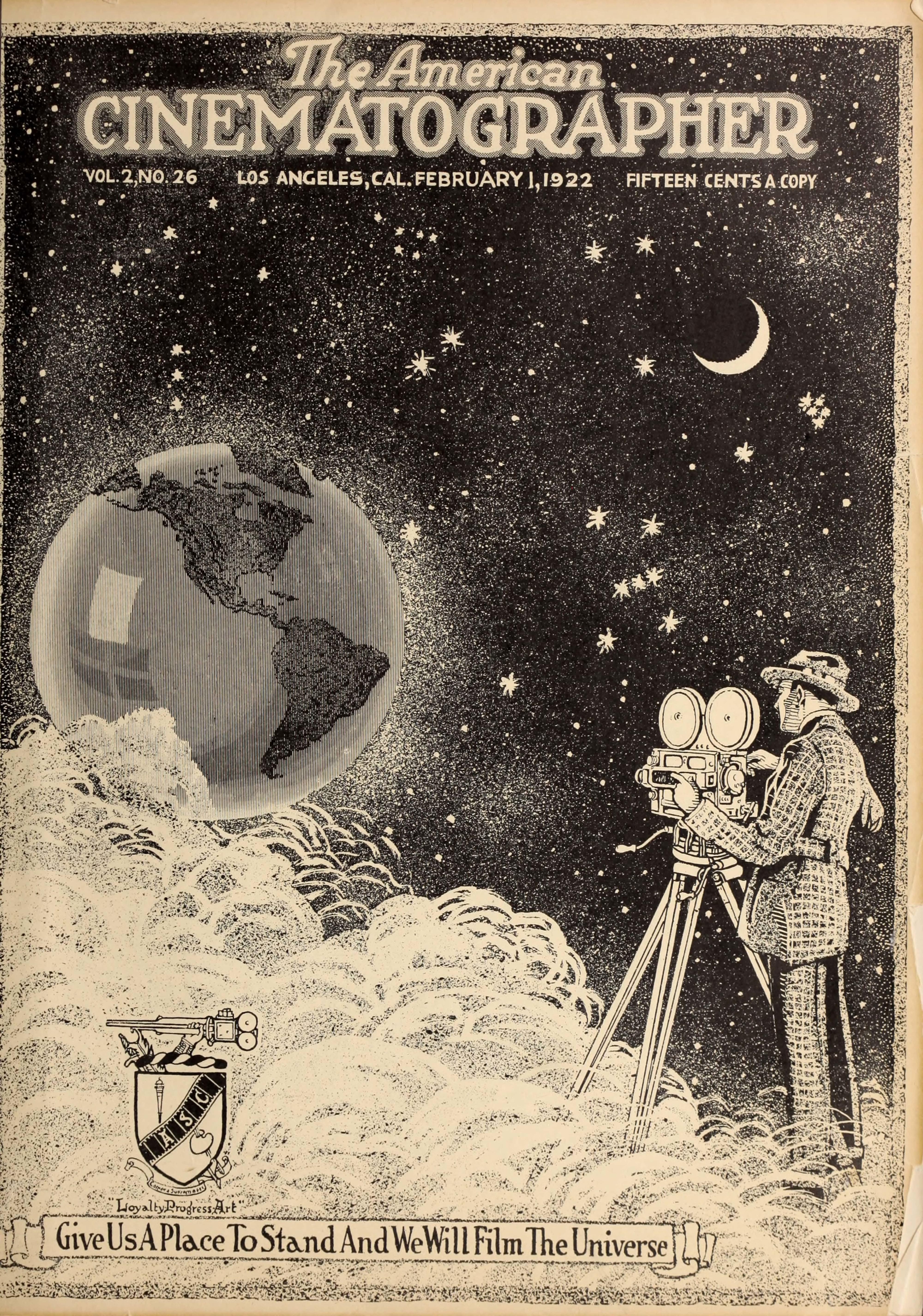

The ASC’s tradition of covering space exploration, via the magazine and its website, continues to this day. Esteemed ASC member James Neihouse, who has trained more than 150 NASA astronauts and 20 Russian cosmonauts to shoot IMAX footage in space, recently wrote an eloquent introduction to our online re-publication of that famous October 1969 issue, noting, “In 1922, decades before the formation of NASA, one of the earliest and most iconic American Cinematographer covers featured an illustration by Lewis W. Physioc, ASC, depicting a cinematographer filming the Earth from an amorphous cloud suspended thousands of miles above the earth with constellations and the moon as the background. The banner at his feet proudly states, ‘Give Us a Place to Stand and We Will Film the Universe.’ Since that time, many ASC members have contributed to hundreds of space-themed motion pictures, both narrative and non-fiction. So it was only fitting that in October of 1969, the magazine would dedicate this issue to the hard work, creativity and commitment of those responsible for bringing the visual story of the Apollo 11 moon landing to the world.”