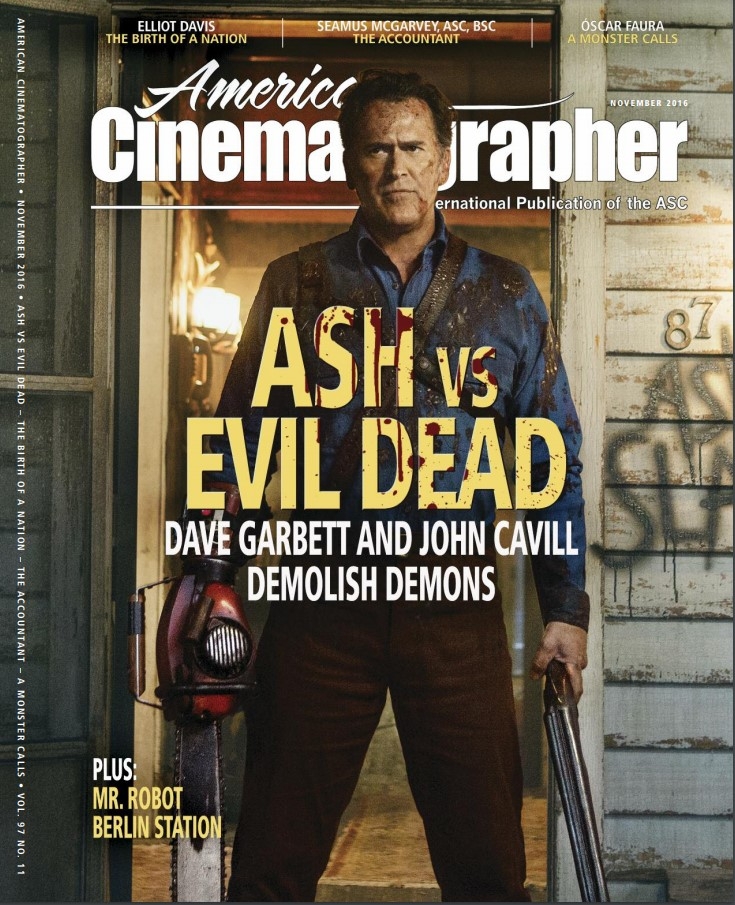

Return of the King: Ash vs. Evil Dead

Cinematographers Dave Garbett and John Cavill help lend stylized realism to this horror-comedy series.

By Simon Gray

Once upon a time, in a cabin in the woods, a group of college students awoke an ancient evil that continues to run rampant through a now 35-year-old horror franchise. Created by Sam Raimi, the Evil Dead films — The Evil Dead (1981), Evil Dead II (1987) and Army of Darkness (1992) — were part scares, part comedy and all blood-and-guts, and they made an icon of actor Bruce Campbell, whose performance as the chainsaw-wielding antihero Ash Williams left fans clamoring for more. That wish was granted when, in 2015, the television network Starz debuted the series Ash vs Evil Dead, which began airing its second season in October.

The series rejoins Ash decades after his last encounter with demon-possessed Deadites. Having traded his gore-soaked chainsaw for a set of false teeth, Ash spends his days as an incompetent clerk at the Value Stop, then squeezes into a girdle before trying to impress the female patrons of late-night bars. In a drug-addled attempt to win over one of those women, Ash reads from the Necronomicon Ex-Mortis, a.k.a. the Book of the Dead, thereby reawakening the ancient evil and leaving himself no choice but to charge back into battle against the hordes of frenzied Deadites and their demonic masters.

Cinematographers Dave Garbett and John Cavill shared the 10 episodes of Season One; for Season Two, Garbett shot seven episodes with Kevin Riley serving as director of photography for three. The series is produced in Auckland, New Zealand, and principal photography for the first season commenced in spring of 2015, with the cinematographers sharing a camera package that included two Arri Alexa XTs and a Sony CineAlta PMW-F55; all cameras were rated at 800 ISO.“The different look of the F55 made things a bit tricky in the timing,” Garbett notes, “but it’s a lot of camera in a lightweight package, making it perfect for Movi shots and when we wanted to just throw the camera around.”

Season One’s first episode — titled “El Jefe” — was recorded in ArriRaw, after which the workflow switched over to Apple ProRes 4:4:4:4 XQ, 2048x1152. Season two continued with ProRes 4:4:4:4 XQ but upped the resolution to 3840x2160. With the exception of “El Jefe,” every episode has been color-graded at Auckland-based Digipost, where Gerard Ward works with FilmLight’s Baselight Two, “utilizing the latest gen-four software,” Garbett says. “Gerard Ward was the colorist for both seasons after episode one of season one. Gerard must often fly solo through the final grade, as we’re usually on other projects when the episodes are finished. I try to at least have a conversation with him prior. He has done a great job using his own judgment — based on original LUTs — in polishing the series.”

“On-set timing from the cameras’ Log C feed was done with Pomfort’s LiveGrade and Fujifilm IS-minis,” outlines digital-imaging technician Christian Gower. “The resulting LUTs were passed all the way down the post pipeline, so dailies and editorial cuts matched exactly what Dave, John and Kevin had created on-set.”

For the first season, the cinematographers worked with a Leica Summilux-C lens package, carrying 18mm, 25mm, 35mm, 50mm, 75mm and 100mm (all T1.4) focal lengths. Garbett recalls, “Episode one featured a lot of torchlight, and I had found during testing that the Leicas had interesting flare characteristics — a lovely blue tone evident through concentric circles. They’re also fast, beautifully made and very compact. [We combined] these with Angenieux Optimo 15-40mm [T2.6] and 24-290mm [T2.8] zoom lenses.”

lighting inside Ash’s bedroom for a season-two episode.

Season Two’s camera and lens package changed to comprise Arri Amira and Alexa Minicameras and Panavision Primo Primes, as well as 17.5-75mm (T2.3), 19-90mm (T2.8) and 24-275mm (T2.8) Primo Zooms.“I had been missing the Primos,” Garbett acknowledges. “Those lenses have an interesting ‘something’ that is hard to intellectualize. It was also easier to obtain two full kits, from a 14.5mm up to a 150mm, with every step in between.” The production also used a small set of Ultra Speeds — 24mm, 35mm and 50mm — for lightweight work on rigs such as the Movi M15.

“The camera kit was provided by Paul Lake and his team at Panavision [New Zealand],” Garbett says. “They were hugely supportive of me and very accommodating of my copious requests during both seasons, and in particular during the testing phases.”

Raimi directed the first episode, establishing many of the series’ stylistic cornerstones. “It was Sam’s idea to use kinetic lighting to inject energy into a shot whenever the Evil Force is present,” notes Garbett. “When police detective Amanda Fisher [Jill Marie Jones] and her partner investigate a reported disturbance in a country house, they slowly move through the dark, foreboding house to an upstairs room, where they encounter a [young woman] they mistake as a victim. There are hard shadows throughout the room, maintaining anticipation and trepidation. Then, when the Deadite possessing the girl reveals itself to the detectives, a wind comes from nowhere and whips the curtains, Venetian blinds and plastic furniture-coverings helter-skelter. One of the detectives drops a [flashlight] that spins for much longer than it should, throwing moving shadows across the room as bulbs flicker and lightning flashes. A sequence that started as quietly ominous is immediately energized into something quite crazy. We used this technique throughout the series to great dramatic effect.”

This lighting motif is complemented with aggressively mobile camerawork — in particular the wide-angle, high-speed Evil Force point-of-view shots — that will look familiar to fans of the Evil Dead films. On those features, Raimi and his collaborators achieved the effect with several well-documented DIY solutions. While Cavill and Garbett had more modern technology at their disposal, they nevertheless embraced the spirit of Raimi’s earlier methods. “There was no particular rule [to how the effect was achieved],” says Garbett.“It just had to feel ‘Evil Force POV.’”

For a scene in which Ash’s boss, Mr. Roper (Damien Garvey), is possessed outside the Value Stop, Garbett used several techniques to send the camera careening over, under and through cars in the location’s large parking lot. Moving shots underneath parked vehicles were achieved with the F55 mounted on a remote-controlled car, while a more elaborate shot hurtling across the lot, up and over shopping carts and into a close-up of the screaming Garvey was done with the F55 on the Movi mounted via a quick-release mechanism to a Technocrane; the arm brought the camera low over the ground and up over the carts before the operator detached and ran with the Movi to complete the shot.

Each subsequent director brought a slightly different approach, Garbett explains. “Rick Jacobson is a big fan of having the camera on the shoulder. He likes to shoot at a quick pace, with a lot of freedom; this is particularly reflected in action-oriented episodes that have a lot of cuts and high visual energy. Tony Tilse and Mark Beesley liked using the 30' Technocrane in Season One and the 23' Scorpio throughout Season Two.The one thing everyone had in common is the desire to keep the camera moving. The Technocrane and Scorpio were run expertly by key grip Kayne Asher.

“The main idea John and I had for the camerawork was to always have some form of movement, a background tremor or resonance that maintains a constant visual tension,” Garbett continues. “We also used moments of emphasis and punctuation. For example, when someone runs into frame from around a corner or enters a room, there’s a quick push-in to a close-up.”

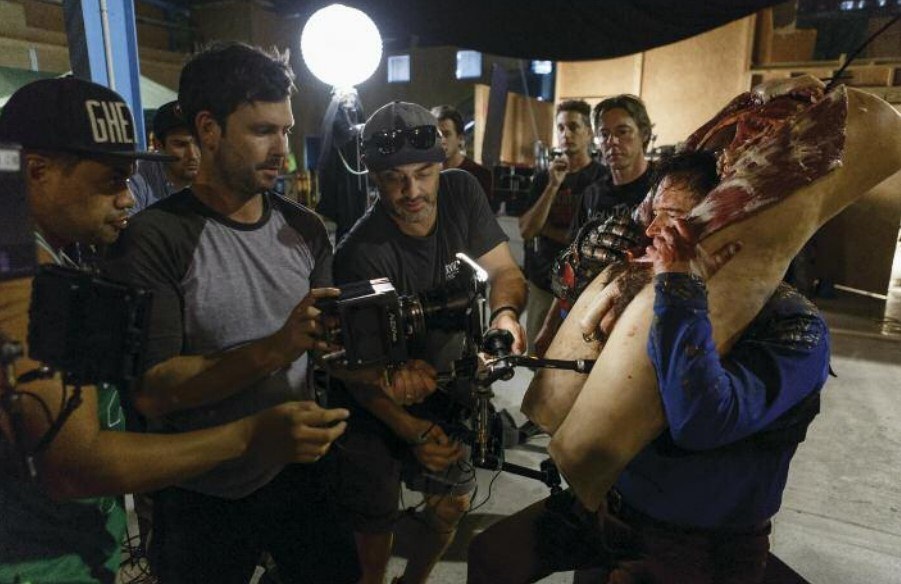

Ash vs Evil Dead has achieved many of its imaginatively gory effects in camera, but the vagaries of a television schedule meant there was little time for testing. “The special-effects and prosthetic departments regularly sent through videos showing us what they were working on, but we often didn’t see the final prosthetic or effect until the day it was to be shot,” says Garbett. Laughing, he adds, “I relied on a combination of previous experience and keeping my fingers crossed!”

Cavill notes, “It was instantly apparent if the effect had succeeded or not, and we had an amazing special effects and prosthetic team that could make any necessary adjustments on the spot. It’s such a good way to work, for crew and cast. Even if the effect itself is completely absurd, achieving it in camera with Bruce and the others really reacting to being hit with gallons of fake blood, bits of gore and heaven knows what else was always gold and very funny — pretty much what the Evil Dead franchise is about.”

“We didn’t over-stylize the visuals, because the subject matter is already so outrageous and insane,” explains Garbett. “The world had to be visually convincing. No matter how insane things get, it should feel grounded, as if these things could possibly be happening just next door.”

Production designer Nick Bassettagrees. “Designing a show with a heavy use of prosthetic, demonic creatures, wirework and hyper-violent action, it was important to keep the sets naturalistic,” he says. “Ash vs Evil Dead is horror, but it is also a comedy, so a lot of effort was put into making the sets as believable as possible while maintaining a slightly whimsical comedic tone. They were designed so that one establishing shot told you everything you needed to know about the space and who inhabited it. Our scenic team did a great job of surface texturing and aging. The attention to detail is a credit to all departments.”

The sets also had to accommodate the show’s bouts of dismemberment and skewering. “They had to come apart for camera and stunt access,” Bassett notes. “In Ash’s trailer, there were wire-rig points and breakaway cabinets and windows, while other sets had soft floors and flyable ceiling pieces. We also had to consider the many gallons of blood that get dumped on the sets. Everything has to be sealed up so the sets don’t turn red over the course of the shoot.

Cavill and Garbett worked with Bassett and the art department to pre-light each set with domestic practicals, including tungsten, fluorescent and LED sources, embracing the “flaws” of each. “We could walk onto a set with the base exposure pretty much in the right place,” explains Garbett. Bassett adds, “The sets were ‘plug-and-play’ — 90 percent lit by practicals. We didn’t overthink the color temperatures, so there is a great mix of light that gives a kind of 1980s look, especially with atmosphere layered in. Prior to Ash vs Evil Dead I had worked on a succession of shows set before the advent of electricity, so the chance to use neon and fluorescent lighting was really exciting, and a lot of effort was put into choosing and building our own practicals.”

Ex-Mortis. Right: The crew captures a shot

of a Demon Spawn attacking Ruby.

The cinematographers tended to maintain a shooting stop of T2.8, and on sets where space was at a premium, the actors were typically keyed by either 650- watt lamps bounced off of calico sheets, LiteGear LiteMat 1 LED units or — most commonly — China balls. For broader soft key lights, the crew turned to 5Ks or Source Fours again bounced off thick calico sheets; they also used this combination as fill-in situations when 20Ks were employed to create sunlight or strong moonlight.

Beyond Ash himself, the character’s 1973 Oldsmobile Delta 88 has become an icon of the franchise. At the beginning of season one’s second episode, “Bait,” the spacious ride plays host to a freewheeling fight scene between Ash, Pablo (Ray Santiago) and the Deadite-possessed Mr. Roper, even as the car tows Ash’s Airstream trailer down a country road. For background plates as well as the location exteriors of the car, the production chose a length of road almost a mile long, lined on one side with 23 sodium-vapor streetlights. “We changed those to mercury lights that emitted a cool white light,” Cavill notes, “and we shot our backgrounds specific to the angles we were going to be shooting in the car on the rear-screen set: out both sides, and from the front looking through the back window at the trailer.”

At the speed the car and trailer were traveling, Cavill tested and found he would need to create the effect of a streetlight moving across the vehicles every six seconds to match the lighting on the backgrounds. So, onstage, Cavill rigged three 6' Chroma-Q Color Force 72 LED battens in a shallow U shape lengthwise over the car,with a slight bias to the driver’s side. Another Color Force 72 provided an unmotivated “amber/sodium traveling light from the passenger side,” recalls Cavill.“On location there were no streetlights on that side. There was nothing but paddocks, but I occasionally needed something between the streetlights on the fill side, and the amber light was a good fit.”

To further help illuminate the car’s interior when there were no streetlights, the cinematographer adds, “I pushed a bit of a cold 1⁄2 CTB, ambient base light into the car, using a T12 through a heavily baffled 12-by-12 Full Silk to create a sourceless night-light; I ran cutters through it occasionally to match the ‘sim trav’ feel. I also used a thin layer of atmosphere through fans across the car, which I believe helped make the backgrounds more credible. I like to use atmosphere on set. It’s moody and it carries the light; I also like the way it reaches into the blacks — it’s almost like free lighting.”

Testing had previously revealed that the 16'x9' rear-projection screens used onstage — which employed 15K and 20K Christie projectors — did not offer a high level of output, so considerable attention had to be paid to eliminating spill onto the screens. “The screens were giving us a base of T2.0 for day exteriors, but for night it was more like T1.0 at 800 ASA,” notes Cavill. “I shot the night [footage] at 1,280 ASA. The LEDs put out a lot of light, but it sprays everywhere. It was an elaborate process, eliminating all that spill with deep, baffled snoots on the lamps; blacking out every surface of the car that wasn’t seen [on camera]; and blacking out the studio from the camera [and] back.”

A Christie 20K projector was mounted from above on a 45' JLG knuckle boom and aimed straight down into a 25'x18' screen positioned over the car in order to create reflections on the front windshield. “We had shot plates looking up and forward at the mercury streetlights so that back in the studio, shooting through the front of Ash’s Oldsmobile, we could play the ‘reflections’ of the streetlights passing over the windscreen,” details Cavill. “It was a finicky undertaking because the Delta is an old car with a lot of curves. The windscreen itself has quite a pronounced curve as it comes into the pillar; it acted as a convex mirror, which meant the reflection screen ended up having to be lowered until it was virtually touching the car.”

Garbett gives due credit to “our fantastic second-unit cinematographer, Andrew McGeorge, and his excellent crew. They did an amazing job over both seasons supporting us, shooting many incredible stunts, action, Evil Force POVs, and often shooting entire sequences.”

In the Season One episode “Fire in the Hole” — shot by Cavill and directed by Michael Hurst — Ash and Amanda fall foul of militia survivalists who believe their friend Lem (Peter Feeney) is the victim of government chemical testing and that the duo are agents. Of course, Lem is in fact a demonically possessed Deadite, and the handcuffed Ash and Amanda are the survivalists’ best hope at dispatching the demon. Not understanding any of this, the survivalists throw the pair into their bunker.

“Michael embraced the idea that the survivalists would have emergency lighting — sodium-vapor-colored practicals set into bulkhead fixtures in the set,” says Cavill.“It gave great justification for keeping [the set] dark and moody.” The cinematographer brought out background details with ambient light created by several 5Ks gelled with 1⁄2 CTB and 1⁄2 Plus Green. “The set did not have a complete ceiling, so I bounced the lamps off the industrial-foil lining on the ceiling of our converted-warehouse studio,” recalls Cavill.

Moving downward through the labyrinthine bunker, Ash and Amanda reach the bottom level only to find the possessed Lem waiting for them. A fight to the death ensues, and Lem attempts to burn the handcuffed pair by spitting fuel ignited by flares taken from the survivalists’ stockpile. Cavill details, “An overhead industrial fluorescent supplied by the art department, gelled with Chrome Orange and 1⁄4 Plus Green, gave a sodium-vapor ambience, and the key lights were practical flares specially made for us. Each flare was timed to burn for 30 seconds and generated a great magenta light — we went through more than 40 of them. It was a great system; once we had set the ambience and created some highlights with more sodium bulkheads in the deep background, all we had to do was light a flare and call action!”

Season One of Ash vs Evil Dead reaches its climax when Ash finds himself back where it all began, at the foreboding cabin in the remote northern Michigan woods. “The cabin and the woods [are the setting for] the last three episodes of season one, so we decided the best approach was to build everything, rather than go to location,” says Bassett. “The woods and cabin exterior were constructed in an old equestrian center, a large space approximately 144 feet by 260 feet, with the major advantage of having a dirt floor, which allowed us to dig and shape the terrain. We built three and a half sides of the cabin, with a partial interior; the tool shed; and the forest, which was made up of 120 trees and many, many trailer-loads of ground cover and windfall that our greens department set up in record time.” The interior of the cabin and its cellar were constructed on other stages.

Appropriately for the genre, Ash arrives at the cabin as the daylight wanes. Gaffer Tony Blackwood explains, “A 20K with Full CTS on a boom lift provided our sun [source], playing over and to either side of the cabin and casting a single shadow, suggesting the cabin itself is an ominous entity. We then positioned T12s with Full CTS to rake through the trees.”

Sourceless night-light in the woods was provided by a combination of 10 T12s and 20 5Ks, positioned on two gantries that ran parallel down each side of the equestrian center. The lamps were skimmed across 12 20'x20' squares of bleached-cotton bounces, six on each side, that were held into the pitched ceiling by wires. “Not a lot of level was required from this soft source,” Blackwood continues. “We often only used one side of the bounces to get some subtle direction. Having the large surface area of bounced light gives lovely reflections on the actors’ skin.”

The actors were often keyed by “a 10-by-10-foot sheet of calico suspended on a T-bar and hit with 5Ks or T12s, depending on the level we were after,” says Blackwood. “The sides were flagged to control [the bounce]. They were called ‘white sticks,’ with ‘black sticks’ being the negative-fill version. It’s a dead-simple, basic tool that worked very effectively.”

“The infamous cabin was an important set to get right for the fans,” Bassett stresses. “It was a direct replica of the Evil Dead II set, with every prop and furnishing lovingly re-created. Bruce Campbell got totally nostalgic walking into the space. It was a great way to end the first season, in the very space where it all began 30-plus years ago.”

- 1.78:1

- Digital Capture

- Arri Alexa XT, Mini, Amira; Sony CineAlta PMW-F55

- Leica Summilux-C; Panavision Primo, Ultra Speed