The Return of the Living Dead: A Comic Strip

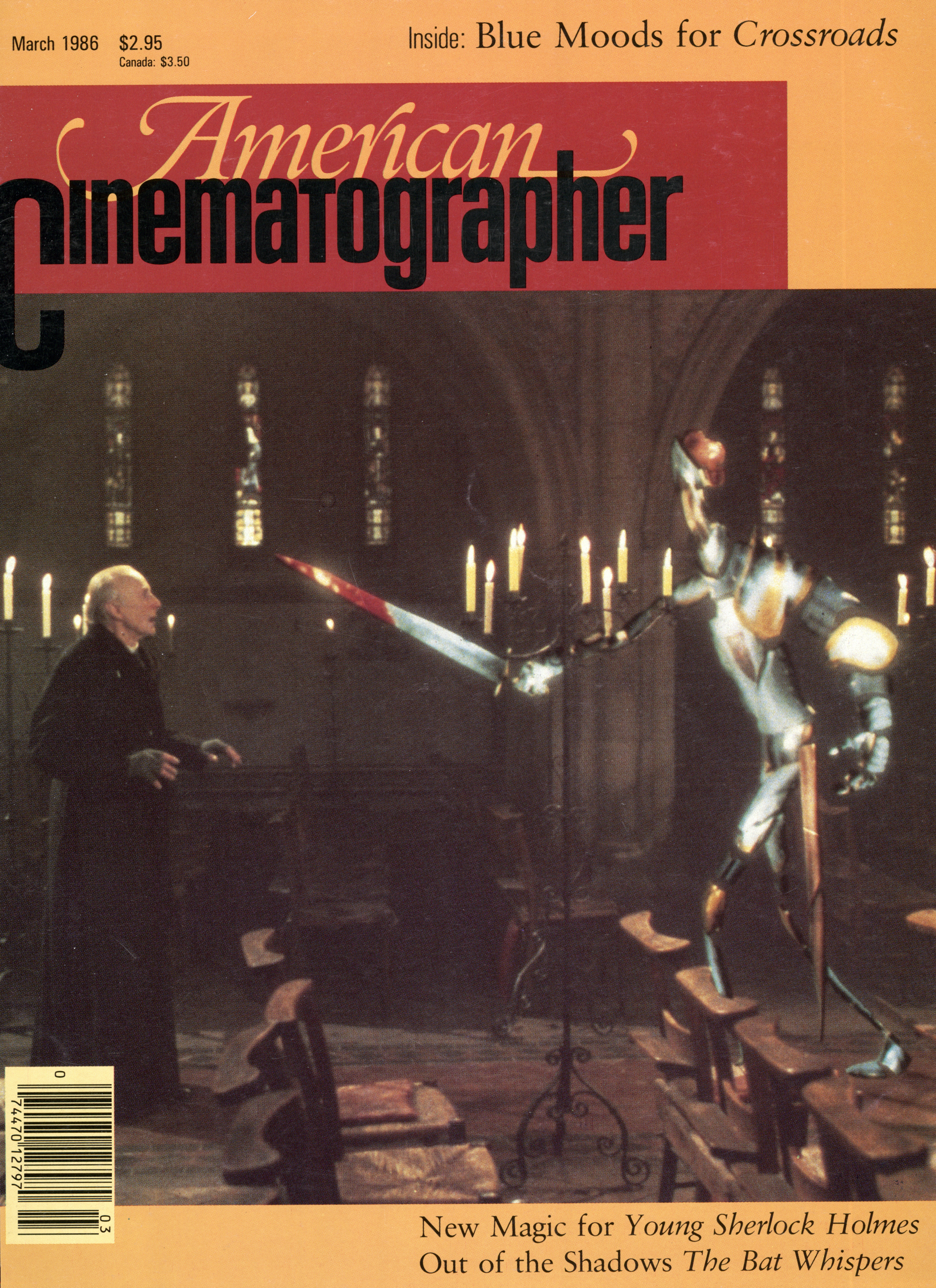

Writer-director Dan O’Bannon, production designer Bill Stout and director of photography Jules Brenner bring the spirit of 1950s horror comics to the big screen.

Photos by Rory Flynn

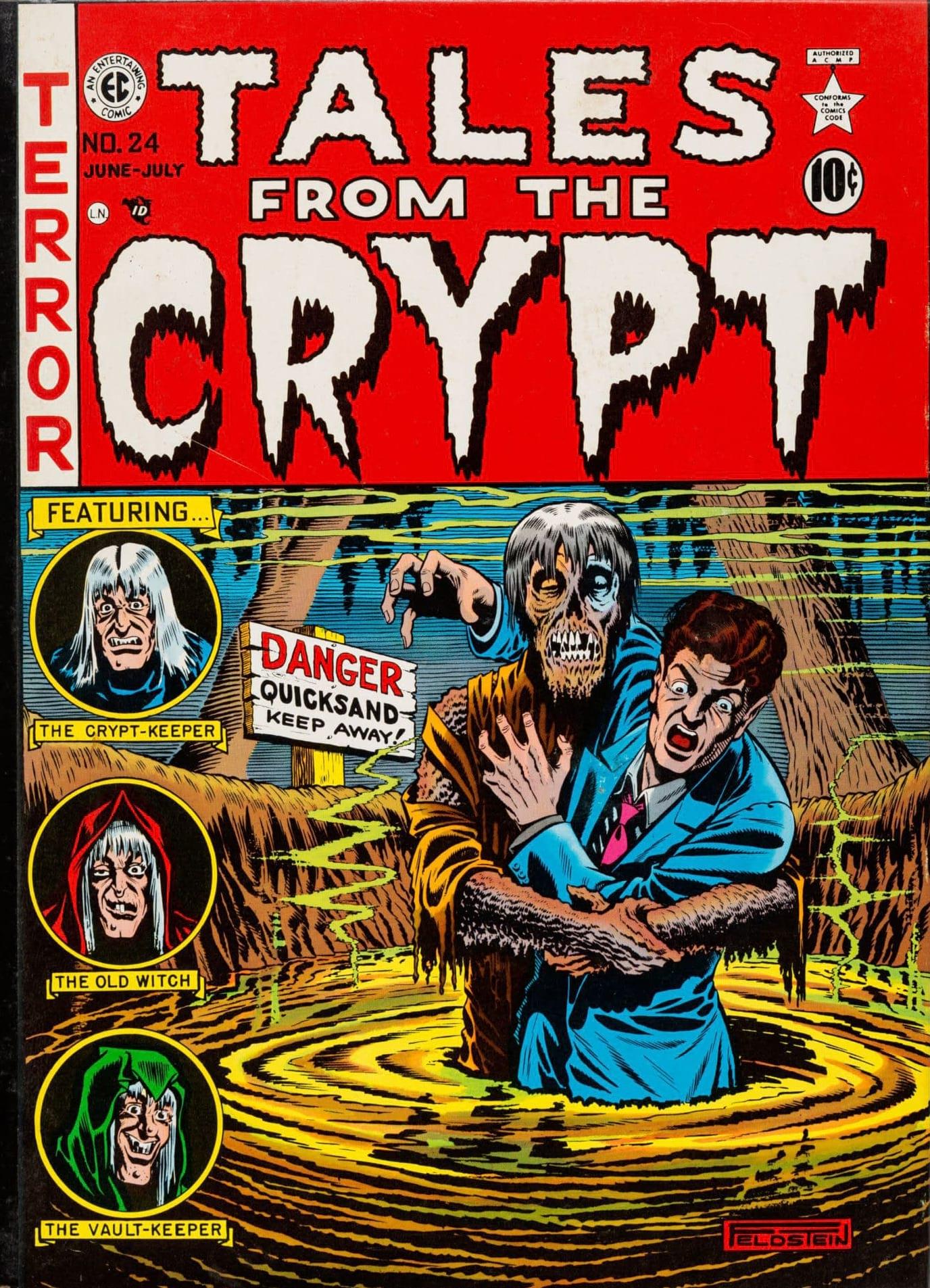

The year 1950 heralded the advent of three cartoon magazines under the Entertainment Comics masthead that would forever change the faces of terror: Tales From The Crypt, The Vault Of Horror, and The Haunt Of Fear. These “comics” specialized in the depiction of hideous cadavers emerging from their graves in the dead of night to exact terrible revenge upon the living. In addition to the creation of a pervasive mood of horror, the EC Comics had developed a highly cinematic style of storytelling, with dramatic framing, high angles, eerie lighting effects, shock cuts and zooms.

In the grand tradition of EC Comics, the action of The Return Of The Living Dead, writer-director Dan O’Bannon’s funny “sequel” to George A. Romero’s seminal 1968 zombie film Night Of The Living Dead, follows the misadventures of a group of teenagers as they attempt to escape from a cemetery where the dead have risen from their graves.

O’Bannon’s script is filled with twists and variations on the rules Romero and his imitators have established governing the behavior of the living dead in film. The walking corpses of O’Bannon’s grimly comic scenario, unlike Romero’s, are virtually unstoppable — they cannot be killed, and their resurrection is due entirely to the introduction of a man-made chemical, Trioxin, into the cemetery soil. The film’s protagonists aren’t ordinary, run-of-the-mill teenagers, but punk rockers, a logical choice since this group is underused in film, and its members surround themselves with death imagery. O’Bannon’s continuous reversals of audience expectation may result in Return Of The Living Dead being long remembered as the first revisionist zombie film.

The film marks O’Bannon’s debut as a director, though he is known as the screenwriter of Alien, Blue Thunder, Lifeforce, and the upcoming remake of Invaders From Mars. It should come as no surprise that he is a confirmed EC Comics fanatic. Nor will many be shocked to learn that his production designer, Bill Stout, is also an avid EC devotee and comic artist of some repute, or that cinematographer Jules Brenner was director of photography on the television terror film, Salem’s Lot. The similarities and differences in style among O’Bannon, Stout and Brenner resulted in a unique collaboration, a highly unusual blend of fantasy and reality which can only be described as “comic book.”

“I don’t recall any moment when I actually decided I’m going to make this movie like a comic book... but I just couldn’t keep Tales From The Crypt out of my head.”

— writer-director Dan O’Bannon

“I don’t recall any moment when I actually decided I’m going to make this movie like a comic book,” said O’Bannon. “I don’t recall any moment when anybody even discussed that, but I just couldn’t keep Tales From The Crypt out of my head. My production designer, Bill Stout, is also intimately familiar with those old horror comics. Between the two of us, we couldn’t resist. It came out not as a conscious decision, never a moment when I said, ‘Let’s set this shot up like a comic book,’ but more like an instinct.”

“The Return Of The Living Dead was just a natural project to bring alive the EC influence,” added Stout. “Since EC Comics were an interest of both mine and Dan’s, we thought it was time to let everyone in on the joke, let them see what an EC Comic would look like on the screen. The black-humored glee, the enthusiasm for horror that those comics had was something that Dan wanted to get into the film.”

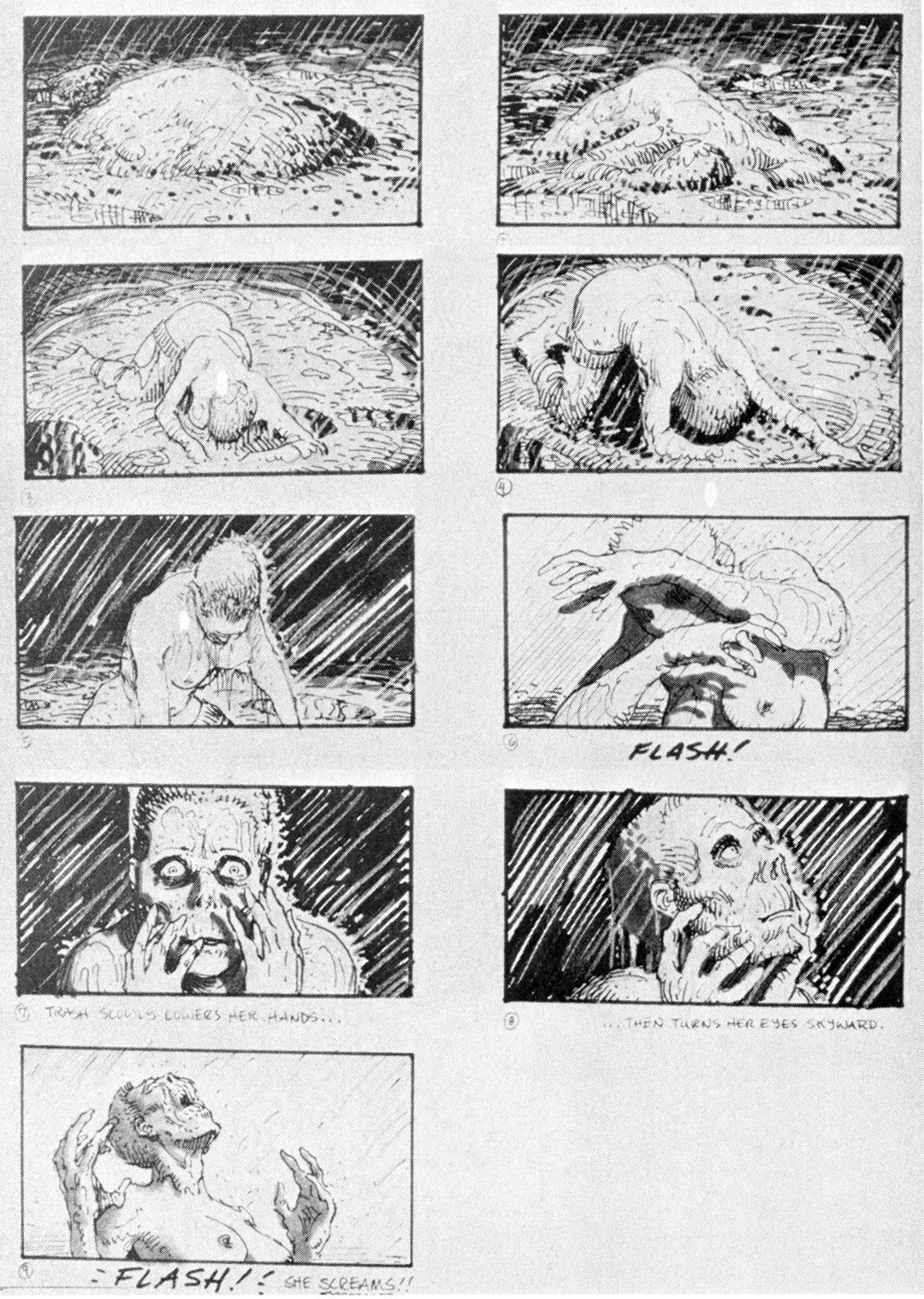

Stout’s own enthusiasm for horror films was put to the test as he worked 16 to 18 hours per day, seven days a week for nearly five months designing virtually every set, costume, prop and effect for Living Dead. “Basically, as production designer, I was responsible for everything but the actors and the sound,” he said. “The production designer works as the director’s eyes, so this film is Dan’s vision as visualized by me. Fortunately, Dan and I were right in sync from the start, so it never became a matter of my sacrificing any particular vision of my own to get what Dan wanted.” Stout found that his extensive comics background made turning out hundreds of storyboards, costume designs, corpse effect concepts and set designs much easier.

“In doing comics, you have to do a lot of drawing real fast, which is a lot like doing movies on paper. It’s not a very large step to go from doing comics to doing storyboards, and if the sets haven’t already been designed and built, you become the production designer too, because you’ve got to put the characters in your storyboards into a realistic setting.”

“When you start off with the notion that you’re going to show people rising out of their graves and eating brains, you’ve got to realize from the start that it’s comic book material.”

— cinematographer Jules Brenner

Because cinematographer Jules Brenner loved the look of Stout’s production paintings, he made an effort to translate their atmospheric quality to film. The two men shared a willingness to collaborate, which resulted in the frequent exchange of ideas as each looked over the other’s shoulder. This intense working relationship is undoubtedly responsible for the fine balance Brenner was able to achieve between Stout’s cartoon style and his own more naturalistic tone. Brenner, who is not a fan of the EC comics, allowed himself to be guided by Stout’s illustrations, while still imposing his own style of motivated lighting and realistic composition, which added a harsh edge of truth to the fantastic events he photographed.

“When you start off with the notion that you’re going to show people rising out of their graves and eating brains,” said Brenner, “you’ve got to realize from the start that it’s comic book material, and you can do almost nothing photographically and it’ll come off that way. Though certain things were exaggerated, most of the film was shot within the constraints of reality at all times. I didn’t do anything lighting-wise that would be unnatural. My lighting and my general approach have a great deal to do with what I observe in nature. I try to find ways to light things and people which will enhance the texture and the mood of the situation, but it’s always motivated within reality.”

Brenner, Stout and O’Bannon shared a dream that they could produce a film that looked like it cost $10 million, even though the budget was many millions less. Despite numerous setbacks and the near disasters that occurred almost on a daily basis during Return Of The Living Dead's eventful six-week shooting schedule, the creative team was grimly determined to make their dream come true. There were two major factors O’Bannon and his crew had to contend with, one of which was entirely unexpected and almost forced the production to shut down entirely. Two weeks before cameras were due to roll, the company that had contracted to build the sets and all of the mechanical makeup effects went bankrupt, leaving many sets and props unfinished. While Stout and his crew feverishly rushed to complete numerous unfinished sets during the day, and another crew was hired to continue the set building throughout the night, makeup maestros Kenny Myers and Tony Gardner were brought in to complete the elaborate special effects puppets. Meanwhile, the crew continued shooting, utilizing the few standing sets and finished effects pieces.

The other factor which slowed production was that even discounting the large amount of makeups required, the film relied heavily on many other kinds of special effects, including rain, fire, smoke, and people rising out of graves.

“The number of consistent special effects prolonged the shoot,” observed Brenner. “We were constantly confronted with effects of all kinds, and the production was in their power. You can’t rush effects, because you’re trying to create an illusion. I tried to reach a certain level of believability in every case, and it’s costly in time to do that. The problem is very familiar to anyone who works in film — there’s never enough time. The film would’ve been a piece of cake, but because of all the special effects, we really could’ve used another two weeks. Time ran out almost on a daily basis.”

Time also seemed to run out even from the earliest days of filming. The first two weeks of production consisted of rainy night shoots in a cemetery set, part of which was located in downtown Los Angeles. The other part was located in a Sylmar, California, olive grove. The fact that the tombstones and vaults were in one location, and the exterior gate and surrounding wall in another, created numerous photographic challenges for Brenner. There were discrepancies between the two which Brenner managed to eliminate in a subtle and effective manner. “I noticed that when we saw the city in the background of the downtown exterior set, there were yellow lights,” said Brenner. “I suggested that we use that idea, and have yellow light present in the cemetery, which became a nice visual element, bathing the punkers eerily before the horror began.”

The rain, however, proved to be the most consistent difficulty O’Bannon and Brenner had to cope with. Unfortunately, the rain was an essential ingredient of the scenario, moving the story forward by transmitting the dread Trioxin chemical into the cemetery soil.

“I should have used fog,” O’Bannon said in retrospect, “but I had it in my head that I didn’t want to be another person copying Ridley Scott, so I was grandly determined not to use a lot of fog effects. There were many times on the set that I wished I was shooting My Dinner With Andre. It was like a nightmare. I cursed myself for putting rain in the movie from the first night I had a rain shoot, when I realized how awkward the rain machines were, and how they had to be dispersed over half a block or more. Also, it doesn’t look like rain until you fine-tune the positions, and the rain has to be backlit or you don’t see it at all. Every time you move the camera position, the rain set-up doesn’t look good anymore.”

“We actually bit off more than we could chew with the rain,” added Brenner. “We had very wide shots downtown and limited rain equipment, certainly not enough for the scope of the shots, but we did the best with what we had. These were sequences that Dan felt very strongly about, and he had definite images in mind.”

Shooting in the rain created further complications in the olive grove Stout had transformed into a Southern Gothic cemetery. The ground of the olive grove was bare dirt, on which the crew planted grass seed which was watered every day during the two weeks prior to shooting. A very tense situation arose when Stout realized that the rain had made a false hill very slippery, and the crew was ready to begin shooting a sequence where ghouls were to rise out of the hill.

“The false hill was covered with mud and fake and real grass to disguise the trap doors the actors would climb out of for the shot,” recalled Stout. “I got very worried when I noticed that the hill was very slick, and I felt that in the night and the rain we had the potential for a real disaster. I staggered all the trapdoors so that each of the actors would have a clear path, even though they appeared randomly placed. Then we devised a system where the zombies would come out in three waves. Before the shoot, I gave a pep talk to the extras, reminding them that they were in a dangerous situation, and I also convinced Dan that a lot of the corpses should crawl out rather than walk out of the hill. We pulled that shot off in one take, and I was very relieved.”

Though the rain effects were difficult to achieve, the film benefitted greatly from their inclusion, which allowed O’Bannon, Stout and Brenner an opportunity to have some fun with a highly cinematic ant hill shot showing how the Trioxin chemical in the rainwater permeated the cemetery soil and the coffins of the dead. The anthill “set” was a box about 4’ wide, built by Stout from his storyboards, and provided a twofold challenge to Brenner, in that his camera had absolutely no leeway to the right or left — a slight pan in either direction would have revealed the edges of the “set” — and the camera had to drop down in sync with the flow of the water trickling into the coffin.

“What l filmed is a shadow of what I saw in my head,” O’Bannon commented. “It’s so diagrammatic and comic bookish, because in a comic book the artists don’t have to draw everything as seen in real life. They are free to take liberties to communicate their stories.” In utilizing this comic book sensibility, O’Bannon was able to anthropomorphize certain objects, like the Trioxin chemical. “I enjoy making inanimate things into characters. I saw the chemical as a character in the film, so I let it act. Its motive, of course, was to get out and get on as many different corpses as it could. Whenever that chemical started floating around, I followed it.” Since many of the corpse characters were either puppets or mechanical make-ups, this ability to instill objects with personality added another dimension to the film’s antagonists.

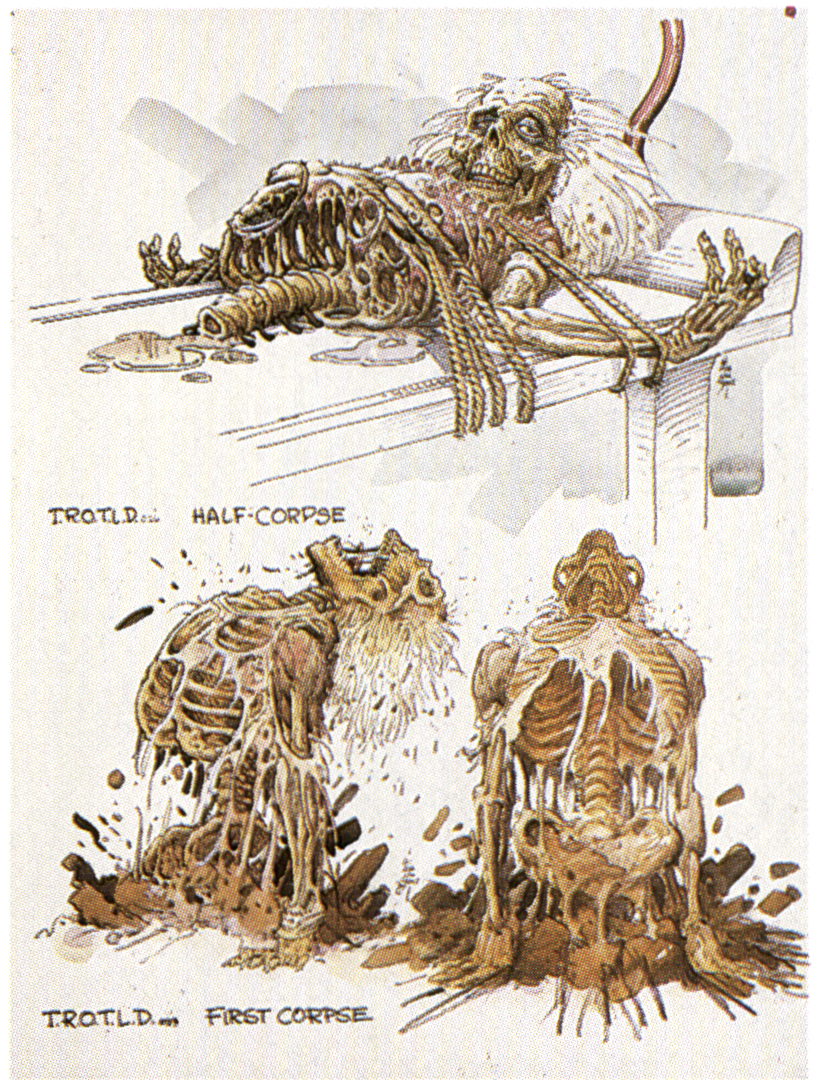

Return Of The Living Dead's primary revitalized villains, the half-corpse, so named because its lower body is hacked off when it attacks the punk heroes in the mortuary, and the Tar Man, a decaying cadaver, required special and often quite elaborate photographic treatment in order to suspend audience disbelief. It was O’Bannon’s intention that both characters appear highly surrealistic and cartoony, in keeping with the comic book tone of the film.

“When Ghastly Graham Ingels would draw corpses coming out of the grave for EC Comics,” O’Bannon recalled, “they all had a particularly limp quality with lots of black shreds hanging off them, and they wobbled on their feet. That’s where the Tar Man came from.” Though Tar Man’s head was redesigned and rebuilt by Kenny Myers to conform more closely to Bill Stout’s illustrations and to include cable-controlled movement for greater expressiveness, Myers and his crew had no time to redo the entire suit, which had been crudely assembled and could not withstand a close-up. Fortunately, within the suit was Allan Trautman, an actor and mime who had the ability to move as if his bones weren’t connected, who breathed life into the character.

“The Tar Man was marvelous,” says Brenner, whose cinematography managed to hide the flaws in the suit, while bringing out the comic aspects of the drippy corpse. “One of the problems with that particular piece was that certain parts of the suit, like the ribcage, didn’t look too realistic to the eye. In certain instances, I lit it in such a way that it would fall off into a darker range so that you wouldn’t see it on film.”

Conversely, in the case of the half-corpse puppet, built by 20-year-old Tony Gardner, the work was so fine that Brenner found he could photograph it in any degree of close-up and it would appear believable. Since the corpse was tied to a gurney for most of the film, all of its wires and cables were hidden underneath, along with the puppeteers who operated the mechanics. Problems arose in photographing the half-corpse because Brenner wanted to be able to show as much empty space under the gurney as possible.

“I made the film for a rowdy Friday night when you go expecting to have a good time and yell and scream.”

— Dan O’Bannon

“We had not prepared for the problem of hiding the puppeteers from the side,” said Brenner. “We could’ve thrown anything over the gurney to hide them, but it wouldn’t have looked right. We had to come up with something that was readily available, but which wouldn’t cheapen the effect. As I recall, we used a stainless steel tray which looked like the stainless steel of the gurney, and I added some pipes and hoses to cover the areas where the puppeteers still showed through. I would not block off the whole area, however, because I wanted to show as much empty space underneath the gurney as possible. I wanted to make the puppet look impossible. Visually, you have to prove that there’s no way to do it. One of the shots I loved in this sequence was a low-angle of the half-corpse on the table, with the end of her spine closest to the camera. It was my idea to have a little fluid just under the end of her spine to simulate oozing spinal fluid. You have to have a taste for these things, but I felt it helped the illusion. Sometimes the movement of her spine was perfectly coordinated with what she was saying and her efforts to lift off the table. Her spine would tighten and move a little bit, drawing a trail of spinal fluid, and I highlighted that with a light so it was very prominent. I just loved her. The puppet was exquisite. When you get something that is so finely designed, you don’t have to hide anything, you want to show it to advantage, and we were able to.”

Brenner was also allowed to show some fine camerawork to advantage throughout Return Of The Living Dead, a fact he attributes to the particular demands of the horror genre. “I like horror films very much,” he said. “A cameraman always looks for opportunities to use the most dramatic aspects of the medium, and certainly horror allows you to get very dramatic in lighting and composition. This film was very attractive to me right away.” Among the opportunities, O’Bannon and Brenner seized upon was the use of subjective camera shots throughout the course of the film.

This technique was applied to great effect in a scene in the chapel where one of the heroes, played by Thom Mathews, becomes one of the undead, much to his girlfriend’s chagrin, and a cat-and-mouse game ensues across the pews. “That was fun,” Brenner remarked. “I operated the camera for this sequence. I first became the girl’s POV on Thom, and then his POV on her. The actors were looking directly into my camera, and I became the other actor. I had to think like that actor at that moment, and, of course, emulate what they did. I carried the scene as far as I could. When the girl threw something at Thom, I actually had her stand behind me and throw the object into the frame at him. These things are kind of challenging and fun to do. It really gets such a strong identification going, and it really helps the pace of the film. The pace was great at that moment.”

Since the release of Return Of The Living Dead in August 1985, the public and critical response to the film has been enthusiastic, and both Stout and Brenner have been singled out for their contributions, while O’Bannon’s directorial debut has received praise for its black comic style. O’Bannon feels that the macabre humor of the film is responsible for its appeal, and is quick to point out that his specialty “is being funny and not funny at the same time. I was born with a simultaneously jolly and bleak outlook on life, and I can see things from two perspectives at the same time. I can see things as simultaneously tragic and comic, and that’s why I had fun doing this picture.”

O’Bannon also wanted audiences to have fun with his film. “It’s a talk-back picture,” he said. “I made the film for a rowdy Friday night when you go expecting to have a good time and yell and scream. It’s sort of addicting, though. For my next picture, I hope to do something low-key which demands a quieter house, and I don’t know if I can stand sitting through it with an audience that doesn’t yell and talk back. It’s such an electrifying jolt of positive feedback.”

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.