Returning the Gaze: Nina Menkes

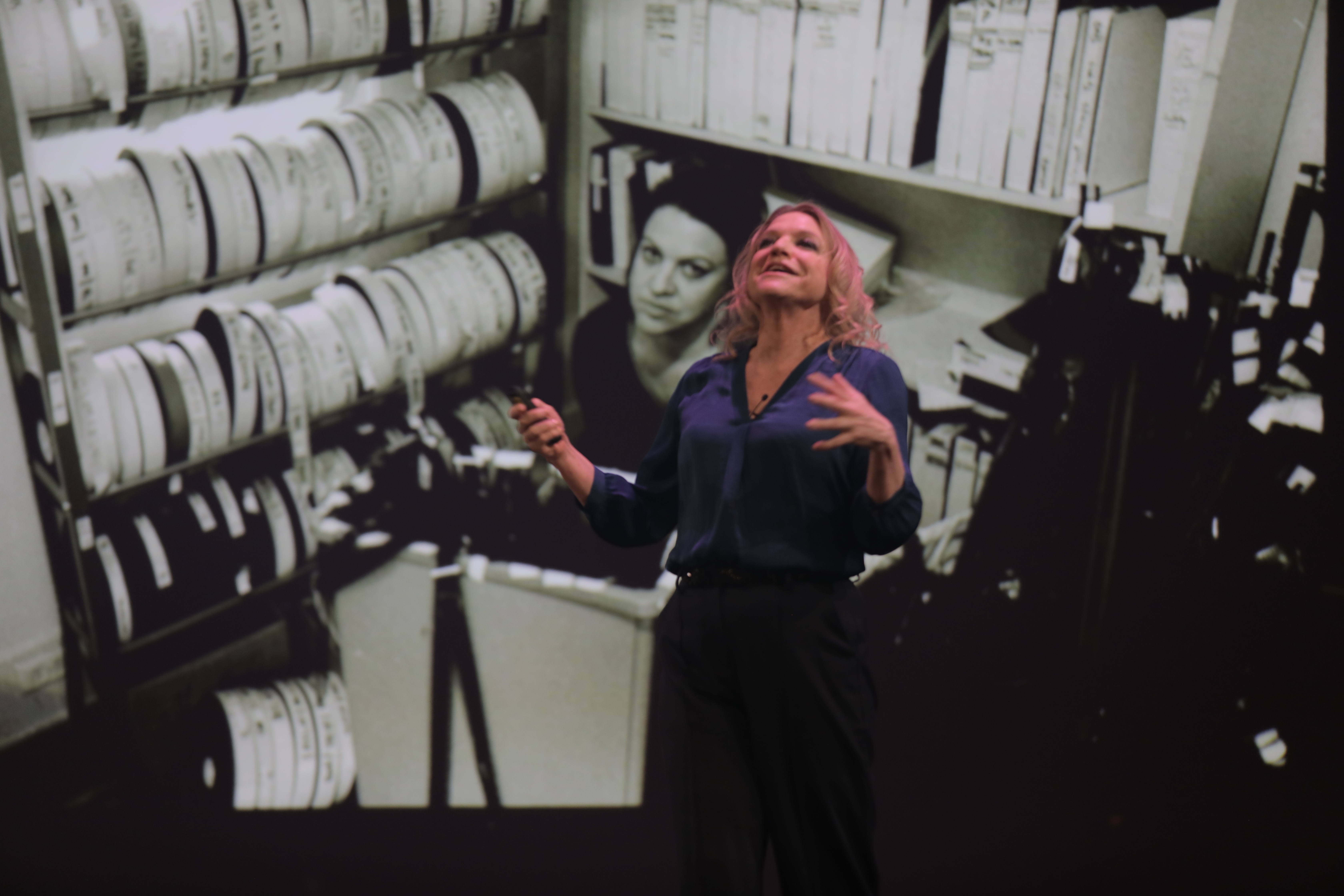

Award-winning director-cinematographer Nina Menkes releases a collection of past work and critiques the male gaze with a new documentary.

Nina Menkes has made a long career — 40 years and counting — of not only making films, but deconstructing them through a radically feminist perspective on cinema, starting with her inversion of the Campbellian hero myth in The Great Sadness of Zohara (1983), and carried through her seven subsequent features, including the convention-shattering documentary Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power (2022).

“Through the lens is how I enter these other

spaces and other levels of reality, where it’s

possible for me to articulate the truth of what

I feel or see in front of me.”

As a filmmaker, Menkes challenges her audience with a languid approach to camerawork and editing, long bouts of silence, dense layers of sound, and alienated protagonists (often portrayed by her sister, Tinka Menkes). Together, these challenges reap the reward of total immersion in a liminal state that, for the most part, possesses all the outward appearances of reality, but girded by existential drama and dream logic.

“My films are not very interested in so-called real life, normal life — they’re interested in the secret, veiled layers of life, and lifting that veil,” Menkes tells AC on the occasion of Arbelos’ release of Cinematic Sorceress: The Films of Nina Menkes, a two-disc Blu-ray set featuring new transfers of Menkes’ narrative work, including 2K restorations of The Great Sadness of Zohara and Magdalena Viraga (1986), 4K restorations of Queen of Diamonds (1991), The Bloody Child (1996), and a remaster of Phantom Love (2007). The collection also includes 2012’s Dissolution. For those not already familiar with Menkes’ oeuvre, Cinematic Sorceress — with its bonus essays, trailers, videos, and commentaries — is a comprehensive introduction to a great American film artist.

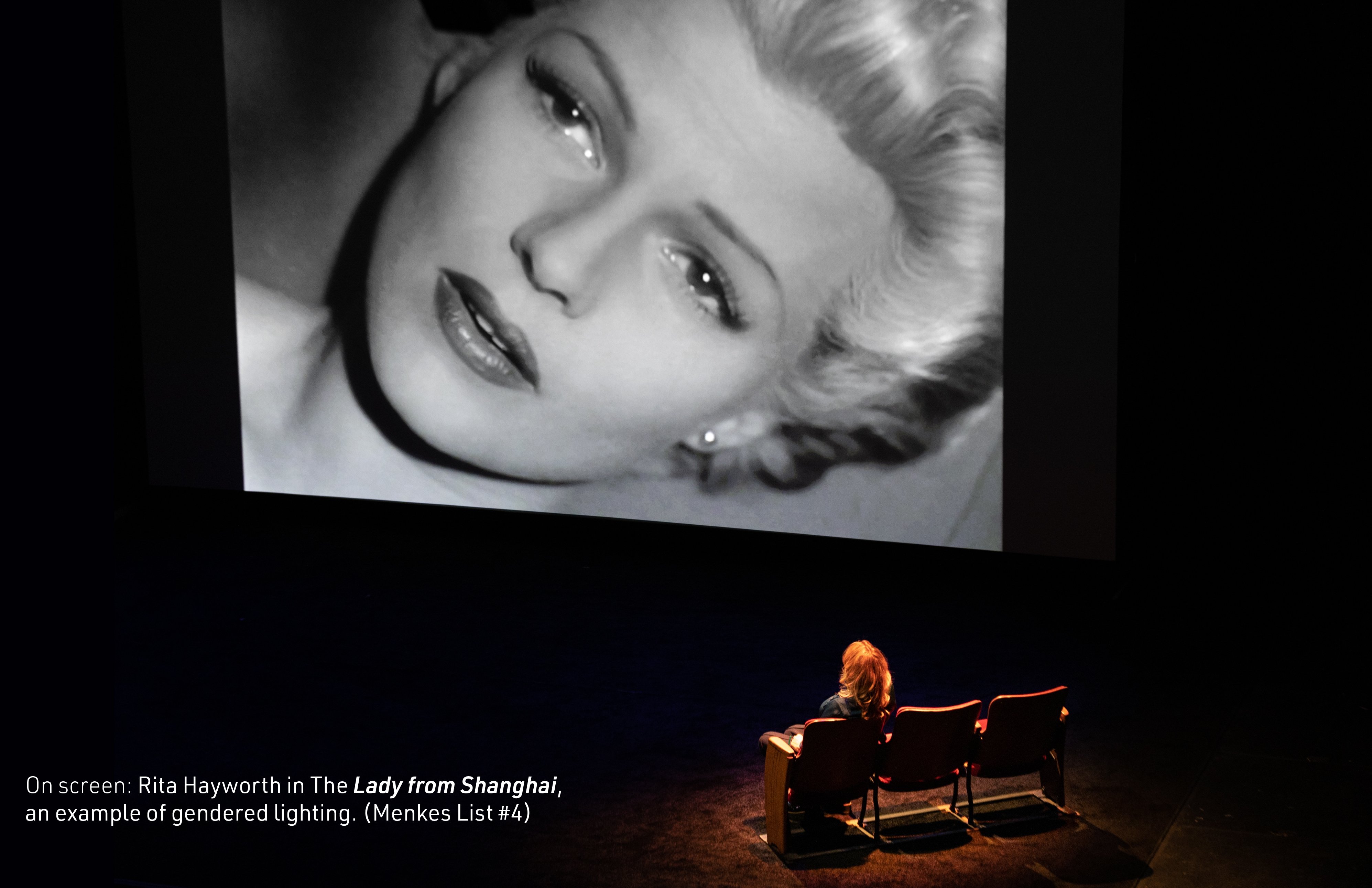

With Brainwashed (photographed in part by Shana Hagan, ASC), Menkes brings her activism into focus through an illustrated talk that deciphers the coded visual language used to objectify women in movies and television. “Of course, in film we’re dealing with fantasy to a certain extent,” she concedes. “But in terms of the sexual difference between subject and object, whose fantasy are we dealing with?”

American Cinematographer: If someone were to ask you what kinds of films you make, how would you respond?

Nina Menkes: For me, filmmaking from day one has been a vocation, and I use that word in the religious sense, in that it’s a way for me to access my own truth.

Is that why you tend shoot your own films as well?

On Phantom Love and Dissolution, I worked with a director of photography [Christopher Soos and Itay Marom, respectively] who was really handling the technical side and the lighting. But even with the films where someone else was in the DoP position, I still always operate, because I realized very early on that when I look through the lens, I have the ability to feel the truth of what I’m seeing, but if someone else is operating and I’m just directing, it’s impossible for me to conjure that feeling. Through the lens is how I enter these other spaces and other levels of reality, where it’s possible for me to articulate the truth of what I feel or see in front of me.

How so?

For example, The Great Sadness of Zohara was designed to follow the arc of the hero’s journey that Joseph Campbell found in myths and fairy tales all around the world. It’s usually a male hero who leaves home and goes into foreign lands, slays dragons, takes the princess or the treasure, goes home, and is crowned king. As a young person at the UCLA Film School, I also wanted to do that story, but with a girl, so my sister Tinka and I went on this voyage to Morocco and Israel: we carried our own equipment and film stock, we stayed with family and at two-dollar hotels, we took buses everywhere. We had no money. We weren’t just filming the story of a hero’s quest, we were actually on the quest ourselves.

The film traces the solitary, mystical journey of a Jewish girl who leaves Jerusalem for Arab lands. After this arduous journey, she’s supposed to go back to Jerusalem to a victorious homecoming. It was just Tinka and me with the 16mm camera on my shoulder, and I walked around Jerusalem with her all day looking for victorious shots, like Tinka’s head and the Dome of the Rock, or something. But when I looked through the lens, I couldn’t roll the camera, and I didn’t know why. So we went back to my great aunt’s apartment, and I went to sleep. The next morning, I realized the end is not victorious.

Later, I read an article that really touched me — I can’t remember the author, but it was a woman who was writing about women’s quest fiction — about how often when the heroine goes on a difficult quest and returns home, her labors are unrecognized, and she re-accommodates to her secondary status. That completely blew my mind, because I was just trying to copy The Hero With A Thousand Faces, but I saw something else.

How did you come to filmmaking as a way of accessing your truth?

I was interested in still photography as a teenager, and then I started working at a Spanish language TV station in San Francisco, where they had me operating a camera. It was just a news camera, but it felt natural to me. I went to UC Berkeley, and then I applied to the UCLA Film School. When I got in, it felt like I’d come home.

Tell me about your journey to finding your voice, and finding the kinds of films that you wanted to make along the way.

I didn’t always know that I was a filmmaker. I didn’t look at other films and say, “I want to do that.” When I was growing up, there was no Internet and there weren’t even video stores, so I didn’t have that much exposure to media. Plus, my mother was anti-tv — we didn’t have one — which is probably lucky.

The very first film I made was at UCLA, [an assignment called] called “Project One.” This is my first semester. We shot non-sync on Super 8, and the school had these machines where the Super 8 picture could sync up with a 16mm magnetic soundtrack. Tinka had recently been very ill, so for my Project One I had the idea to make a film about two sisters — her and me, and her illness — but at first, I struggled with the conceptualization of it. I was having lunch with a friend, and I told him “On the one hand, I want it to be Neorealist, but on the other, I want it to be surreal.” This friend, I don’t remember his name, but I’ll never forget what he said: “Why don’t you do both?”

My mother had this very beautiful, magical apartment in Berkeley, and Tinka was at home because she was around 16 at the time. I planned for two actresses to be in this film — one was supposed to play me, but the one who was going to play my sister didn’t show up. I asked Tinka if she wanted to play herself. She said, “No, that’s bad karma.” So she played me, and the other girl played the sick one.

Tinka has played the lead in many of your films. Is she always playing a version of you?

Those characters are completely different from me as a person in real life, but also my films are not very interested in so-called real life. They’re interested in the secret, veiled layers of life, and lifting that veil. So, Tinka’s characters are definitely not me, but she’s not Tinka either. She’s an archetypal figure — you might call it the enraged, wounded feminine or something like that. She’s the shadow side of these cinematic babes that we’ve had shoved down our throats for years, and her character is saying “No, thank you” to all of that.

Back when I started to make films, people weren’t really talking about these issues — not widely — and yet Tinka’s character stood for that from very early on. In 1986, I showed Magdalena Viraga at UCLA with a bunch of other film students in attendance, and this 18 or 19 year-old boy, an undergrad, he stood up and said, “This is the most violent film I’ve ever seen. You do things that even Brian DePalma doesn’t do.” That’s another comment I’ll never forget, because there’s one moment where someone gets stabbed. But more violent than DePalma? More like, it was violent to his worldview, to his understanding of cinema, to the way he wanted to see women on the screen. Tinka is this figure of resistance against and rage at the meaning of women in cinema.

Your films are distinctly visual, but with a distinct and textured sound component. What’s your process for bringing these two elements together?

It was a process of discovery. When I started putting sound to the picture, my approach was to create a whole world in the sound, but for The Great Sadness of Zohara, I had absolutely no idea what to do, so I started playing. We had editing rooms at UCLA, and I spent an entire quarter sitting there for hours, trying different sounds. I told one of the teachers, “I feel like I haven’t gotten anything done, because I haven’t found a single sound that works.” And he very wisely said, “You’ve eliminated the things that don’t work.” And not long after that, I found something that did work. Once I understood the concept, I started building sounds for every single shot.

How did your technique evolve as you continued to make films?

It got faster. My basic approach — the way I use sound to bring out hidden layers of reality — hasn’t really changed. There’s a delicate balance between picture and sound. They have to work together to make meaning.

You say in Brainwashed that all of your films have been “centrally concerned with expressing the abject feminine and the wound that is carried deep inside.” How long have you felt this way about your work?

I got more and more angry with the lack of opportunities for women filmmakers. I made The Great Sadness of Zohara and it won a special jury prize at the 1984 San Francisco International Film Festival. We showed it at UCLA, and everyone thought it was incredible, but nobody else seemed to care. Then I made Magdalena Viraga also at UCLA, and that film won a Los Angeles Critics Award. It went to Toronto and 40 festivals all around the world, but I couldn’t get arrested in Hollywood. I wasn’t what they were looking for. This was in the late 1980s, so the alienation of that central figure in my films only intensified. It’s a deeper inner condition in the films, but it was certainly impacted by my experience in Hollywood. I used to think, “Well, my films are kind of experimental.” But isn’t David Lynch experimental? I’m not more experimental than that, unless you consider it experimental to not have naked women in your film, and part of my problem is that I refuse to do that.

Is that what you meant, when you say in the documentary that “as a filmmaker and a woman, you found yourself drowning in this vortex of visual language from which it was very difficult to escape?”

I was drowning in it in the sense of its impact on me psychologically. There’s almost no woman who hasn’t felt that terrible thing where your sexuality — which should be an embodied part of your subjecthood — is split off into this “object zone,” and it’s a terrible feeling. But instead of acknowledging that it’s a terrible thing, it’s glorified and glamorized in our media. It’s confusing, especially for teenage girls. They’re depressed, they have body dysmorphia, eating disorders, they want to kill themselves.

In your documentary, you refer to film Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” where she writes about how the pleasure of looking and the effects of cinema are very much intertwined, which reminded me of an article from AC November 1934, by Karl Struss, ASC, who writes that “in modern days, dramatic cinematography must strive to convey an impression, not alone of actuality, but of perfected actuality. Our aim is to show players in settings not merely as they are, but as the audience would like to see them.”

That would be the opposite of what I do, which is showing the audience something it doesn’t want to see. This thing of “making it pretty,” especially when it comes to women, and the way they’re made pretty on screen is very insidious, actually. I was speaking to editor Nancy Richardson, and she told me that [the name of the visual effects company] Lola is now used as a verb to make women look younger and thinner. Actresses have it in their contracts for 25, 100 hours of “Lola.” Of course, in film we’re dealing with fantasy to a certain extent, but in terms of the sexual difference between subject and object, whose fantasy are we dealing with?

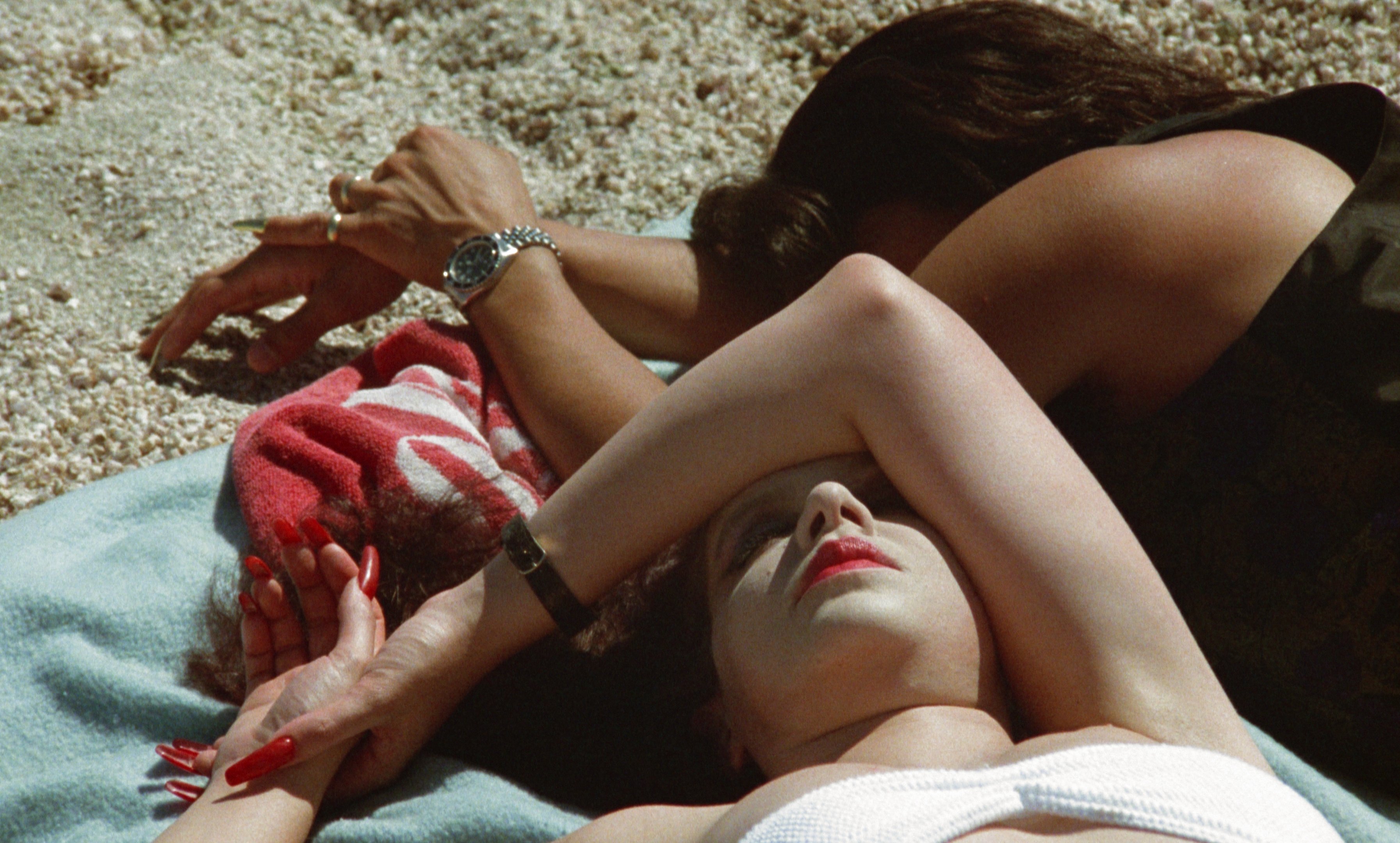

In the documentary, you look at the ways shot design perpetuates male dominant positions of power, and how these designs are repeated throughout most of film’s relatively short history as an art form. How did you start to break these design elements down? And what was the process of drawing your conclusions? Are the answers out there, hidden in plain sight?

They’re hidden in plain sight. It’s almost like a law. We have maybe 200 examples in the film, but we could easily have made a five hour film with 600 examples. If you’re paying attention, you realize how systemic it is.

It seems like this is something that artists and audiences have struggled with since long before the advent of cinema. In 1972’s Ways of Seeing, art critic John Berger applies the concept of the male gaze to classical painting and uses Manet’s 1863 painting Luncheon on the Grass as one example, but it no doubt goes back all the way to the Renaissance and beyond. How do you reckon with this?

It’s an old story. But in the United States, women are not an oppressed minority, we’re an oppressed majority. How is it possible that we go along with this shit? I don’t know why it’s so hard to throw off that yoke, but the wound goes deep.

Berger and Mulvey were reckoning with a different media ecosystem than than we have now. It’s much more aggressive and pervasive. Again, how do filmmakers cope with with this? To bring it back around to your documentary, does it require a total re-conception of our visual language, as director Charlyne Yi suggests, or the destruction of pleasure, as Mulvey suggests?

“Pleasure for whom?” That’s the key question. Pleasure for him. It’s time to not only serve the pleasure of the heterosexual male. That’s one form of pleasure. The last thing I want to do is be prescriptive and say you can’t shoot a certain way. Just be aware, because it’s a question of dosage. If you get a whiff of some toxic chemical for two seconds as you’re walking down the street, you’re not going to die, but if you lived next to a toxic waste factory for 25 years, you’re probably going to get cancer.

Mulvey writes about “new developments and film technology” in the 1970s — meaning 16mm — that allowed film to be not just a capitalist product, but something artisanal. And if the status quo is to perpetuate these stereotypes of patriarchal visual language, what’s it going to take for cinema to truly compete with the dominant position, now that almost everybody’s got a digital camera in their pocket?

It’s going to be very difficult. One of my friends selects short films for Sundance — he’s been doing it for years — and he told me that before everyone had a smart phone and editing software, they would get maybe 300 shorts per year and select maybe 15 or 20. Now, they get 3000 submissions a year, but still only choose maybe 20. So the fact that everyone has access doesn’t mean that really unusual, exceptional work is getting made, because most of it is just imitating what’s already out there.

As Eliza Hittman so succinctly says in my film, the male gaze is not just behind the camera, it’s who decides what gets seen, who’s in charge of distribution, and if you get distribution, how much money is put into advertising? Statistics show that films directed by women routinely get a fraction of the advertising budget that films directed by men do. It perpetuates itself. But if I can be optimistic, I would say the success of Brainwashed has been heartening.

At the end of your Brainwashed, you talk about shifting the audience’s understanding of the subject-object relationship away from an objective attachment to women. Can you elaborate on this?

It’s really about claiming your own perception of yourself and the world. The editor of Brainwashed, Cecily Rhett, has a 13 year-old daughter who dresses up and asks her mom, “How do I look?” She’s trying to train her daughter to ask herself instead, “How do I feel?” It’s just so deeply ingrained in us that as as women, how we look is in the first position. What I try to do with my work is to find the truth of what I’m looking at. How does the character feel, and what kind of shot expresses the truth of that feeling? And that’s just a very different approach.

Visit Nina Menkes' personal site here.