Robby Müller and Paris, Texas

“The adventure of this film is finding the images for the story.”

This article was originally published in AC, Feb. 1985

By Barbara Scharres

Production photos courtesy of Agnes Godard, AFC — who assisted Müller on this picture.

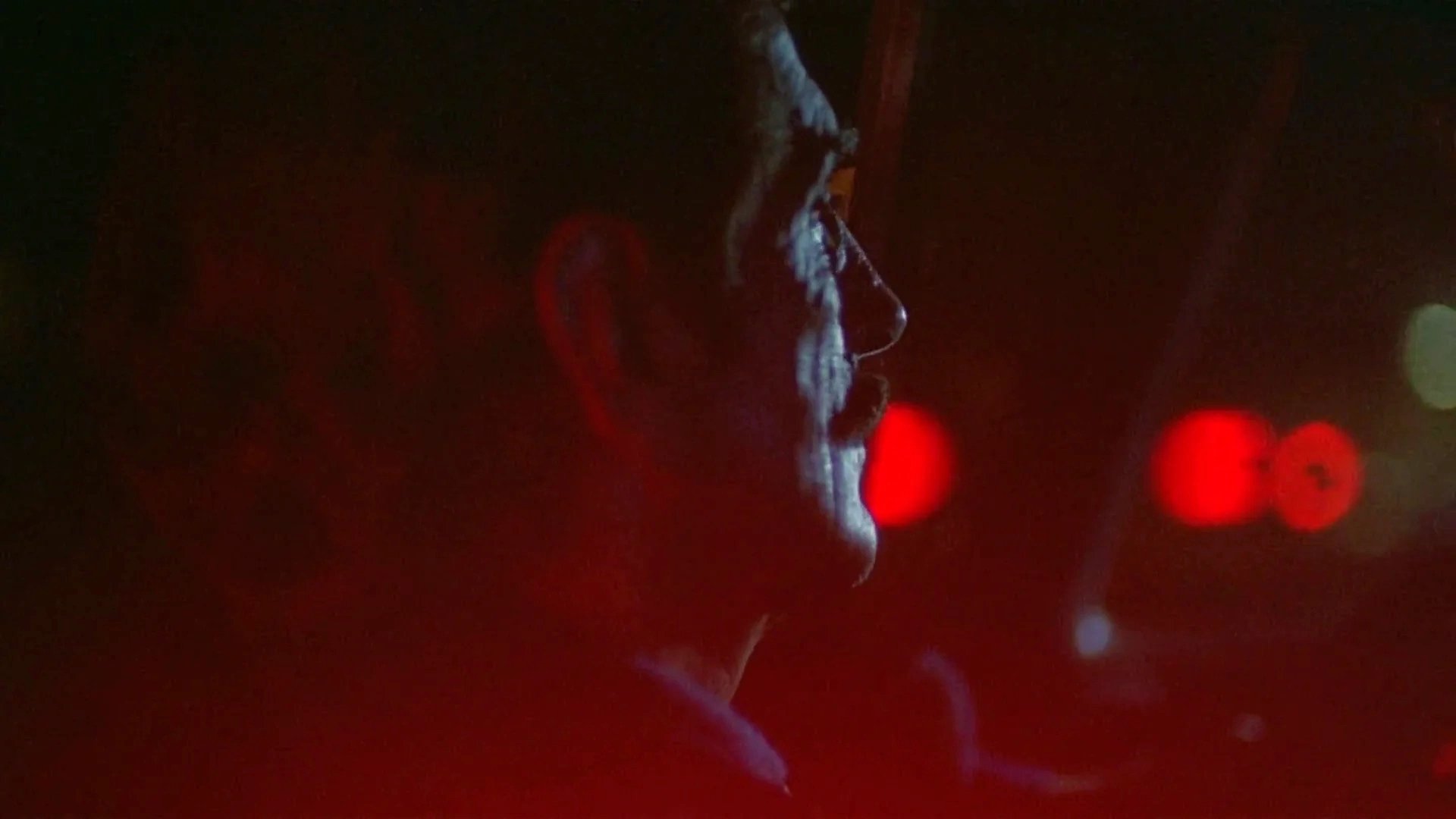

A scruffy man, looking a lot like a human scarecrow, lurches out of the hard, brilliant light of the desert into a tiny bar in a ramshackle adobe building. As he scrambles desperately for something to drink, finally scooping a handful of shaved ice into his mouth, you notice the extreme, cool blackness of the interior, the thin, bright neon of a beer sign and the savage whiteness pouring through the screen door in the background. This doesn’t look like movie-set light; it looks and feels real. With great simplicity the scene registers the uncompromising extremes that eyes can see but that movies often hint at with well-modulated facsimiles rather than reproduce. For the viewer it duplicates that moment of changeover from blazing light to darkness where the vision barely functions, where emerging details are singular and eerie, and where spots of brilliance, like the sunlight through the screen door, almost hurt.

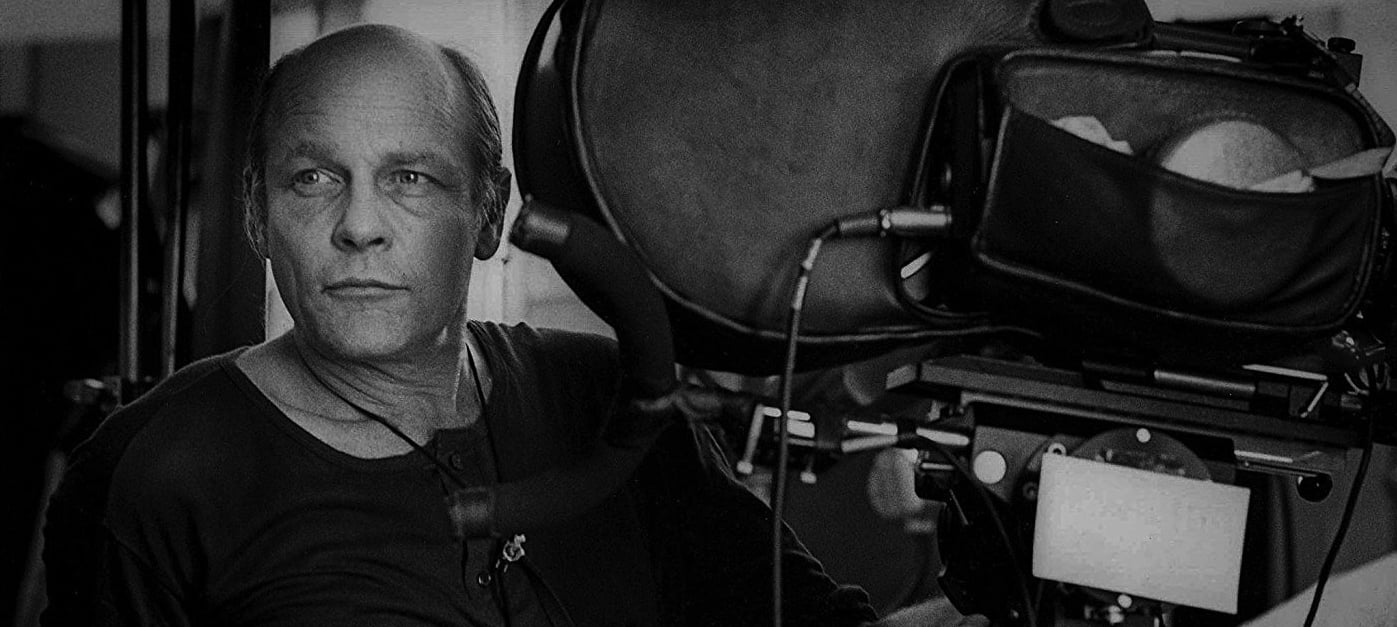

The film is Paris, Texas, directed by Wim Wenders, in which Travis (Harry Dean Stanton), the thirsty man on the verge of collapse, is about to start a journey to re-discover his past. The startling reality of the light is the work of director of photography Robby Müller [NSC, BVK], who believes that the magic of the film image depends upon the viewer believing in the reality of the light.

“Wim and I seem to have the same opinion or feeling about how something should be shot.”

Müller very rarely discusses technical matters. His job is working with light and as far as he’s concerned, that process begins and ends in his head. He’s not interested in talking at length about cameras or film stocks or lighting instruments, and indeed, these things seem to matter to him only in the most rudimentary way. He’s a stubborn proponent of the idea that he does the work and that one way or another the tools will serve his purpose, whatever those tools happen to be, but the simpler the better. He says, “I’m not a technical crazy. It takes a very long time before I get interested in a new camera, because what’s the difference — I have to light the scene anyway, I have to use my own brain and my taste and my personality — that doesn’t change.”

Müller came to the conclusion early in his career that there had to be something more to making an image than having high-tech equipment at your disposal. “So, I brought myself back to looking, really looking and thinking over what it’s all about. And when you strip everything down, it really is a lens, film, a camera and one knob - on and off.” Looking and thinking are essential to the Müller way of working and are the subjects he returns to again and again in discussing photography.

Paris, Texas was the occasion of a reunion for Müller and Wenders, whose long standing working relationship on eight films between 1969 and 1977 includes False Movement, Kings of the Road and The American Friend, all considered to be landmarks of the New German Cinema. They first met while working on a film for a Munich television station on which Müller was, for the first time, director of photography, and Wenders was assistant director while still a student at the Cinema and Television College in Munich. Müller shot Wenders’ exam film, Summer in the City, and from that point onward was his only cameraman until American union difficulties prevented Müller from shooting Hammett at Zoetrope Studios in 1978. Once their partnership was disrupted, clashing schedules kept them apart for another five years, while Müller increasingly worked in both Europe and the United States, most notably shooting The Left-Handed Woman for Peter Handke, The Glass Cell for Hans Geissendorfer, Class Enemy for Peter Stein, Saint Jack and They All Laughed for Peter Bogdanovich, and Repo Man for Alex Cox.

Müller relates that his greatest worry the first day of shooting Paris, Texas was that time and working with other people had changed Wenders and himself enough that they could no longer work together with their former ease. After two days of working the tension dissolved and they again found themselves thinking along the same lines. Müller says, “Wim and I seem to have the same opinion or feeling about how something should be shot. We don’t have to talk about it very much; mostly not at all.”

“You can make something important in the way you construct the image.”

March 1985. A harsh blue sky forms a backdrop to the underside view of a sweeping tangle of highway interchange ramps in the light of mid-day. In the foreground, in a rusted pick-up truck, Travis is telling his younger son Hunter (Hunter Carson), from whom he had been separated for four years, of his plan to go to Houston to search for the boy’s missing mother. As the two talk, reaching a new plateau in their wary relationship, the space of the film frame is carved up by angled concrete that veers off into the distance, giving father and son alike the vulnerable air of children in a landscape made for aliens.

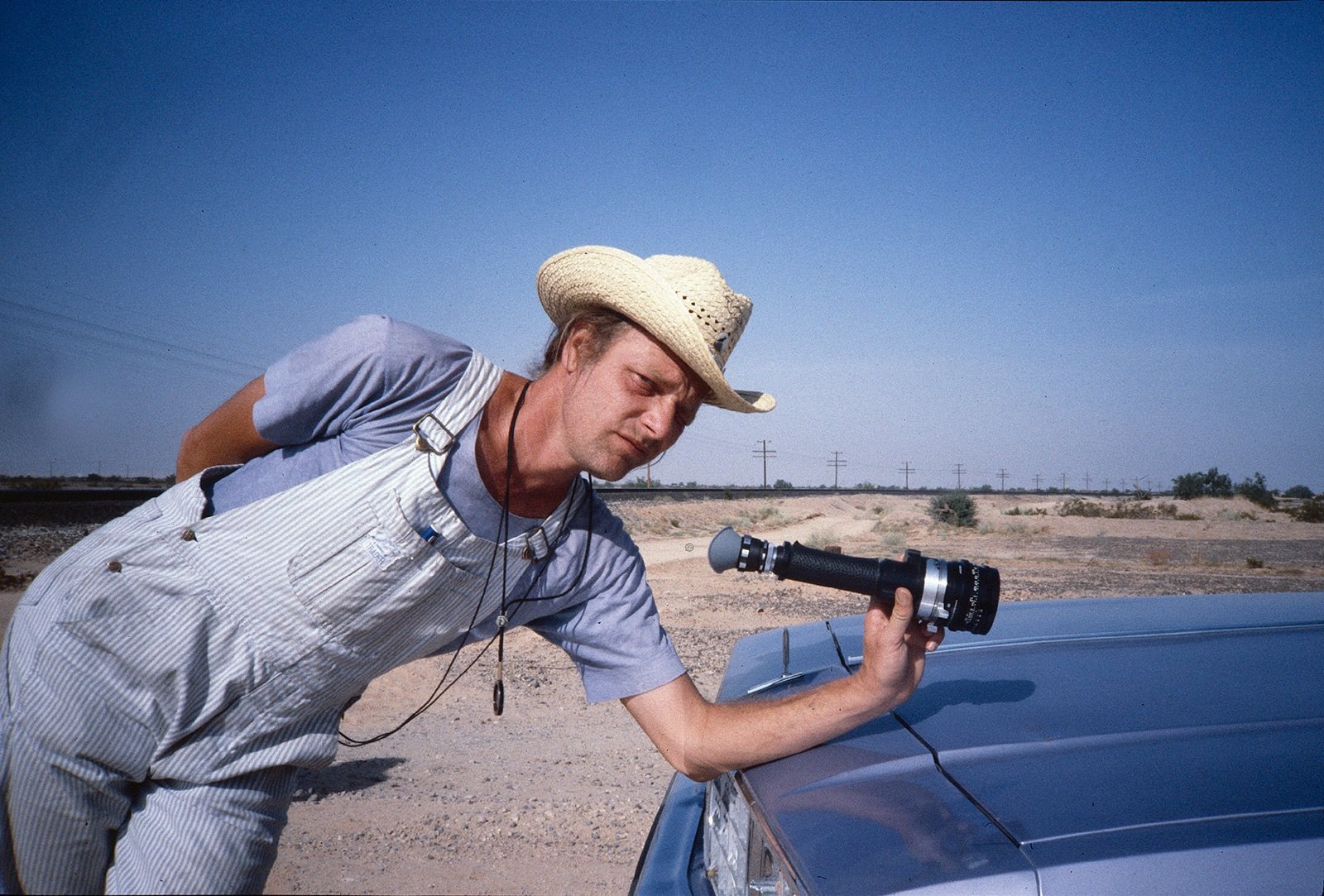

Müller cites his awe, as a European, at the vast strangeness of the western American landscape as a liability that had to be turned to his advantage in shooting Paris, Texas. “At first,” he says, “you just do a double-take — what am I doing? This is too big, too beautiful; it is so exotic, so strong.” He was concerned that the American uniqueness of the locations in downtown Houston, the Texas desert, or on the astonishing network of highways, could overpower the story, and he and Wenders discussed how to avoid what Müller calls “showing off” with locations while not avoiding the striking images the landscape provided.

He says, “What I hate in images is when people find a nice location and they celebrate it too much. I think it’s very bad for the story you’re telling, because what are you filming, the story or the location? I hate seeing films where they make typical, picturesque shots so you can feel that they are proud they found the location and are going to show it off whether you want it or not. That’s where you should have control over the mechanisms at work.” He doesn’t want the audience to be visually led into accepting a film as a kind of travelogue of familiar views, so that someone’s first reaction might be to poke their neighbor and say, “That’s beautiful - have you seen that?”

Müller credits Peter Bogdanovich with teaching him something valuable regarding working with colorful locations when he was shooting Saint Jack. He says, “That was also a very exotic background — Singapore, Asia, extreme colors, extreme heat, rain, the extreme clothing of the people in the street. Of course, in that situation you are very proud when you manage to light things well. Peter taught me about throw-aways: ‘OK, Robby, very nice — throw it away.”

According to Müller, throwing something away means, “Be proud of the lighting but don’t celebrate it and turn it into something extra. The moment you start celebrating what you did you stand still, you are not going one step forward. It becomes a mannerism — there is no development anymore.”

Müller works at striking that balance between throwing something away in the picturesque sense and keeping the spirit of it. One small example of his handling of the problem was in lighting one of the desert motel room locations for Paris, Texas. The almost catatonic Travis has been brought there by his brother Walt (Dean Stockwell), who has come to take him back to Los Angeles after being summoned by a doctor from the Texas border town where Travis was found wandering. In this scene, Travis is oblivious of his surroundings and Walt is distinctly out of his element in this solitary cabin in the middle of nowhere. The room is the archetypal ancient motel room in its dusty, beat-up ambiance, but has a few unique features in its garish red bedspreads and the signs of the zodiac stenciled on the wall over the beds. Müller shot with the room partially in shadow, with the daylight slanting through a window at the foot of the beds. While the more colorful aspects of the room are fully discernible, they do not overtly come to the viewer’s attention.

“Showing off” is what Müller equates with singling out portions of the image in a way that is inconsistent with the story. He says, “What I try to avoid is pointing at something so that I become patronizing to the people who look at the image. I’d rather give the audience the chance to discover it themselves. For me, that’s a very important thing — that you still have things to discover for yourself.” As an example he mentions the scene in which Travis stumbles into the dark bar. “You don’t have to say everything to make yourself clear. I don’t feel the need to see his face that well because I’ve got most of my information anyway. In this specific scene, if I start lighting up the whole bar it loses a lot of its character — it becomes a film set.“

Another result of Müller’s dislike of calling attention to portions of the image in an artificial way is the fact that he and Wenders never work with a zoom lens. He says, “I think that’s an easy way and a lazy way and a way that’s not well thought out, of lifting out something that’s important.” As the more difficult alternative, he says, “You can make something important in the way you construct the image.”

“The images must have power.”

The locations for Paris, Texas were carefully selected by Wenders, who had spent three months traveling around Texas through both cities and rural areas to find the appropriate settings for the story. Houston, Port Arthur, numerous small towns and points between were finally chosen. Müller emphasizes that finding locations has always been integral to the development of the films he has worked on with Wenders, partly because the films are shot in chronological order and because often, the story undergoes change and development as a result of their interaction with the location.

“Everything starts with the finding of the location. We find the locations that fit the story and fit the man or woman who has to move around in that place, so a lot is already given. The same with the light, actually, because you choose a location, whether you’re conscious of it or not, because you have a certain light there.” Since Müller’s preference is always to use natural or available light, he works to preserve and use the light he finds as much as possible without the addition of what he calls “made” light. He says, “I tend to very much respect the light that is already there on the location.”

Shooting a film in chronological order is Müller’s favorite way of working, but a procedure he has found in practice only in the films of Wenders. He finds that for himself, the advantages far outweigh the disadvantages, “There is more of a development in everything. You can invent new things and fit them in the film and you have no continuity problems. You can change the story halfway through without being bothered by an ending that you might have shot already. You really work from A to Z; you can grow in the film. Everybody goes with the story. When you shoot the end of the story, the shooting is finished.”

The script for Paris, Texas was written by American playwright Sam Shepard, but by the time shooting was in progress Shepard was working as an actor in the film Country, making his participation in changes more difficult. The story was sometimes changing and evolving from day to day as Wenders worked with writer L.M. “Kit” Carson on the adaptation, and the ending was not really determined until it was time to shoot it. Müller and Wenders sometimes discussed the logic of various endings as they drove from one location to another.

Rather than considering this kind of uncertainty a problem for his work, Müller feels that he is stimulated by the risk. He expresses a preference for jumping right in and shooting a film rather than for being involved in lengthy pre-production work or working with storyboards, because he thinks that the film really happens when it is actually being made. Müller quotes a line from an unrealized Wenders script to describe their working method for previous films - “The adventure of this film is finding the images for the story.” Since they work without a storyboard, it is entirely possible for immediate impressions on the location to play a large role in shaping the story.

“Because I’m not an American and not living in this country, and because I don’t even know the country that well, every place I go I’m kind of baffled by what I see.”

Shooting in the Southwest, Müller was particularly conscious, as a stranger in unfamiliar surroundings, of trying to wipe away pre-conceptions and let his wonder or worry come to the surface and work for him in approaching an image. He says, “Because I’m not an American and not living in this country, and because I don’t even know the country that well, every place I go I’m kind of baffled by what I see. I choose a point of view that somehow translates how I feel or how I felt the first time I saw something. The impression it makes on me flows into this whole decision making.”

Seeing things through the eyes of an outsider is important to Paris, Texas. Travis, it’s main character, emerges from an alcoholic haze and a four year-long state of amnesiac wandering to rediscover the look of the world and to find himself no less an outsider in his brother’s home in Los Angeles where his seven year-old son Hunter is being brought up by his brother and sister-in-law. He believes his only hope of belonging somewhere is to reunite his violently separated family by taking the boy and finding Jane (Nastassia Kinski), his wife, a hope that will not be realized in the way he imagines. Müller lets his own acute observation determine this newly seen world. His faithful perception of light gives the viewer a sense of recognition that heightens the reality of the action. The interior of an air-conditioned car is filled with odd reflections and the light has the strained look of light coming through heavy glass, emphasizing the enclosure. The warm, verging on cool, light of late afternoon reflecting on the varnished surfaces in a small-town barroom depicts that moment when daytime heat dies and evening cool begins. The shadowed illumination of a large room lit by one bare incandescent bulb hanging from the ceiling conveys an intimacy that has a raw edge to it created by the harshness of the light.

Müller is unaffected by pre-conceived taboos, and dares to compose shots that others might categorically avoid. When Travis scans the periphery of downtown Houston with binoculars, he catches for a moment the sight of an American flag snapping in the wind at the top of the steelwork for a new building. This shot might be a cliché under almost any circumstance, yet, like other views in Paris, Texas that are so indigenously American they could almost parody themselves, Müller brings it off with cool objectivity. There is the impartial quality of real light in the light he captures on film that lets images speak for themselves in the context of the story. He says, “I don’t try to tell my own, separate story with the camera.” Müller’s way of working is based on careful observation and thought to arrive at images that are not pat solutions to narrative problems.

As an example of how he arrives at a solution he describes the filming of a scene for The Left-Handed Woman in which the main character is waiting for a train. “We just sit for a while and observe what it could mean for this woman, what she would see in the state of mind she is in. You can film the arrival of a train in a thousand ways, but mostly it is done so that the train suddenly comes into the shot, or you are filming it from far away, but still you are filming a train. We filmed the grass that is pressed down by the air pressure of the train coming into the station before you see the train. When you take the time you find things like that. You don’t have to do camera acrobatics to make it impressive. Looking around and observing — it is a more quiet way of working. It’s not just knocking off shots.”

He elaborates on this method with, “When you observe it as work you get the impression that nobody is working. I hang around and look at it for a while and slowly find an angle, then try another one. At a certain moment it satisfies me and it happens.” The subjective nature of the decisions he arrives at in finally filming an image makes Müller reluctant to theorize too extensively about how it happens because “very much comes straight out of the belly.” He says, “Of course you have your own little theories, your little place in your head while you’re doing it, but it’s somehow too private to put in words. At a certain moment you come to a solution that is very difficult to theorize about, difficult to defend.”

In discussing what is most important to his way of shooting a film, Müller recalls that while shooting The Left-Handed Woman director Peter Handke said to him, “The images must have power.” Müller says, “You can interpret power as making an image that really hits you in the stomach, that is very strong in the movement inside the frame or the movement with the camera, and you have physical power. But, you can also make a frame in which the power doesn’t come from the surface.”

While this kind of image making requires patience and thought on the part of the cinematographer, it correspondingly demands thoughtful viewing on the part of the audience. He notes, “Nowadays my kind of power is much less used because it involves some risk. If you don’t want to do camera acrobatics to create a powerful image then the other alternative is finding things inside the frame. Very often, on first sight, the image may be boring to the audience because nowadays no image stays on the screen longer than two seconds. It makes consumers out of people and keeps them busy all the time. The eyes never come to rest, and the moment they have to look for themselves, if things are not put on a plate in front of them, they think it’s boring. Not everyone, but in general.”

“It’s the subtleties that are the most difficult things...”

Travis sits in a tiny, near-dark cubicle with an expanse of mirrored glass in front of him. There is a shaded desk lamp on a shelf beneath the glass and a plastic sign that says “poolside” above it. He holds a telephone to his ear. Suddenly, the glass becomes a window and a small room behind it is revealed when a young woman enters, flipping a light switch and flooding the room with light. Her space is like a miniature stage set decorated with a piece of nude statuary and some beach toys and plants to simulate a poolside patio. The woman wears a mini-dress approximation of a nurse’s uniform. The scene is from Travis’ point of view and he sees her clearly. It is not until the woman beings primping in the glass and speaking without making eye contact that the audience, along with Travis, realizes that he is sitting in front of a window of one-way glass; he sees her but she sees only herself in a mirror.

The peep-show location for Paris, Texas is the setting for the crucial reunion between Travis and Jane. The end of the road in this film is the painful confrontation between husband and wife who have not seen each other for four years and who will only meet on either side of the peep-show glass, never seeing each other simultaneously. According to Müller, the problems in shooting these scenes were not great once he achieved the correct light levels to produce the desired effect. Although it had been suggested that he simulate the effect of the one way glass using plain glass, he says he never considered it — that it was actually easier to use the real thing.

When shooting from Travis’s point of view it was necessary for Travis to be dimly visible by the light of the small lamp and by the light spilling through the glass from the other room, while simultaneously “Nurse Bibbs” and eventually Jane, had to be brightly lit in the manner of the themes in the various peep-show rooms. In the final scene between Travis and Jane, shots from Jane’s point of view will show a spot of lamplight burning through the mirror until Jane turns off her ceiling light in order to try to see Travis’s face. At that point the mirror effect reverses and she sees him illuminated by the lamp while he sees his own reflection. Müller says, “It demanded certain light levels — I had to take great care that I didn’t overdo it and go wrong there. It’s the subtleties that are the most difficult things — it’s like a lot of people can play the piano but what makes you a good player is the graduation in volume. It’s not finding the notes in the right order, it’s how you touch them.”

A real complication in shooting these scenes was the fact that they had to be shot quickly and there was no room for trial and error in the lighting. He says, “There was not enough time, not enough money and we only had enough negative to complete the scene and no money to buy more. The last shot was also our last roll.” The last scene between Travis and Jane ends with an arduous and emotional eight-minute single-take monologue by Nastassia Kinski. There was one 1,000’ roll of negative left and no possibility of shooting again at that location. Kinski came through without a flaw, and Müller relates that they had to time the shooting with a period when the jukebox at the raucous bar next door would be off for ten minutes straight, predicted by a crew member stationed there with a walkie-talkie.

“People assume images come from tricks that can be duplicated. By duplicating the technology you get the same images. ‘Just tell me how you did it...’”

On the subject of the technology of his profession Müller takes a stand that may be considered radical in its rejection of mechanical solutions to problems. He says, “When a woman is supposed to be beautiful in a scene very often the system is to put in a filter to soften up the features a bit so she looks younger and more beautiful and so on. That would be my last resort. I always try to solve a problem with light first, just light.“

After Paris, Texas won the Palme D’Or at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival in its world premiere, Müller found that he was increasingly approached by critics and interviewers who wanted an inside story on what they assumed to be the technology involved in shooting the film.

“In Paris, Texas they wanted a hold on how it was done and didn’t even look too closely at the image. They started asking me right away what filters were used. For many interviewers it was a bit frustrating talking to me because no interesting technical details came out of it. I finally said to a man, ‘I’ll make a bet — the first person who can name more than one filter I used gets $1,000.’ Because I didn’t. People assume images come from tricks that can be duplicated. By duplicating the technology you get the same images. ‘Just tell me how you did it. . .’ It was just working with light, that’s all, no filters. It’s not that I’m against it in principle, but in this special film and in lots that I did I found other solutions. I feel that I betray my own profession when I solve problems with what I think are cheap tricks. You can filter or do tricks that blind people — say the filter is so strong you don’t need to light very precisely anymore.”

Müller’s preference for basic equipment and for a philosophical and intellectual approach to work problems leads to his eschewing many recent developments in equipment, particularly the use of a video monitor in conjunction with the camera. “When I get a camera from a camera rental the first thing I do is let them take off all the toys.” Having tried this system on one film he says, “I’m sure it’s sometimes very useful, but I mostly didn’t need it at all and it was only a burden — all those extra cables restricting your movements. What disturbed me very much was that people on the set were not concentrating anymore. They were standing behind the monitor as if it were happening there and not on the set. The whole moment of truth was gone. You could check everything, re-do everything and you have endless discussions. There is a moment when you do a shot, there must be a moment, when you say, ‘OK, we have it,’ and maybe you’re not so sure about it, but sometimes you must put a period there and go on. The video always delayed that moment.”

Working most effectively and enjoyably on a film for Müller also means operating the camera himself. “Doing my own operating is 50 percent of the fun of my whole job, and when I light a scene I think of a special framing and movement.”

Having worked with an operator only once in his life, he concluded that that way of working was not for him due to the inevitable difficulty in achieving the movement and framing he designs for a scene through another person who may conceive of those things quite differently. “Moreover,” he adds, “I don’t like to have too many people around the camera. I can concentrate better when there aren’t too many people involved in this big, black machine. I think it’s better for the actors too. The whole communication is easier with fewer people to deal with — you have an ideal triangle from director, actor, cameraman, back to director.” Following this line of thinking, Müller never works with a second unit, feeling that it is a catastrophe for one cameraman to have to imitate another’s work. He would rather work longer and shoot the entire film himself, choosing his films carefully so that this is possible.

“‘What’s a key light?’”

When Müller was finishing secondary school in his native Holland he thought he would probably go on to the university and study mathematics and physics. Since he began to have sneaking doubts about the mathematics and physics part of the plan, he chose to do his two years of compulsory army service first.

With time to think it over he was increasingly influenced by the fact that none of his friends, all musicians and painters, were going to the university. The catalyst for his new career direction came when he met someone who had attended the Film Academy in Amsterdam and realized that this attracted him. The Academy only owned two cameras, one 16mm Kodak Special and a 35mm that barely worked, yet despite this dearth of equipment Müller specialized in camera because he didn’t think of himself as a writer. Then, for five years, he worked as assistant to Dutch director of photography Gerald Vandenberg, who also had a strong preference for the use of natural light.

Müller says that initially his consistent use of natural and available light was an accident of circumstances. Holland had no real film industry at that time and the few films made there were very low-budget. Often a production could barely afford the rental of a camera let alone have enough money left over for lighting equipment. He says, “I used to work with that light and play with it and wait for certain light because all the things you could do in a big production were not possible. You couldn’t make the light you needed so you had to choose locations because of the light.”

Categories and systems of working, when applied to lighting, are things that Müller feels inhibit people unnecessarily and sometimes prevent creative solutions to problems. He relates his first experience in dealing with studio-trained technicians. “They said, ‘Where do you want this spot?’ and I said, ‘There.’ ‘So this is going to be your key light?’ I really upset them by saying, ‘What’s a key light?’ And they said, ‘Oh, you mean the other one is the key light?’ I said, ‘Call it what you like.’ For me it’s not a standardized thing. When you need a key light it means that you need another light to complete the system, and I never thought about that. I just needed the light that I needed. To give it a name made no sense to me.” Müller finds that one of the advantages of working on independent films is that the technicians are younger, more curious, less formed by rigid ideas of how things should be done and more vitally interested in their work. He considers it a good sign when the gaffer comes to the dailies, and he encourages discussions about lighting among the people he works with.

Müller rejects the idea of “style” as a certain predetermined look that a cameraman applies to a film, and finds that it’s a misconception on the part of some directors that the director of photography is there to provide an attractive wrapping for a film. He reveals that he once upset a director by saying, “Actually, you are responsible for how the film looks,” because the director obviously hadn’t thought of it that way.

On choosing directors he says, “In your career I think you end up working with very special directors. They fit you and you fit the director. More and more you single out who you would like to work with, and when it works out you stay together.” He believes that cameramen should make their choices carefully. “As a camera man you are a kind of sailor. If you really figure out how often you are at home and how often you are working it often turns out that seven months of the year, that’s more than half the year, you are doing your job. It makes perfect sense to me that for those seven months to do something that makes sense for your life. This is the first and very last time you are on this planet.”

Müller’s other feature credits include Breaking the Waves, Down By Law, To Live and Die in LA, Barfly, Korczak and 24 Hour Party People.

He was honored with the Camerimage Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006, and the ASC’s International Award in 2013.

You'll learn much more about his exceptional career here in our memorial tribute.