Roma: Memories of Mexico

Alfonso Cuarón re-creates 1970s Mexico City for his highly personal, black-and-white, large-format feature.

Unit photography by Carlos Somonte. Additional photography by Javier Enríquez. All images courtesy of Netflix.

Roma is Alfonso Cuarón’s most autobiographical movie to date. The director behind the ambitious thrillers Children of Men and Gravity has turned inward for his latest film, which is drawn largely from characters and events from his childhood years in Mexico City’s Colonia Roma neighborhood. It is also the first feature he has shot on his own.

The movie screened at the Venice Film Festival — where it won the Golden Lion — followed by Telluride and Toronto. It was also awarded the Bronze Frog at last year’s Camerimage International Film Festival. Roma’s debut on Netflix was preceded by a theatrical release.

The story, set in 1970-’71, focuses on Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio), a nanny who, along with best friend Adela (Nancy García), works for a middle-class family on the verge of a difficult transition. Father Antonio (Fernando Grediaga), a doctor, is leaving mother Sofía (Marina de Tavira) for his mistress, but as far as their four children know, their dad is simply away on an extended business trip.

Cleo’s romantic situation comes to parallel that of Sofía, to whom she provides unwavering support. When Cleo becomes pregnant, boyfriend Fermín (Jorge Antonio Guerrero) skips out to focus on mysterious martial-arts training in a remote village. While preparing for impending motherhood, Cleo unwittingly finds herself in the middle of what is now known as the Corpus Christi massacre, in which students marching for democratic reforms encounter a fierce paramilitary group.

“That’s when Chivo said, ‘Stop fooling around. You should do it.’”

Cuarón did not set out to be his own director of photography, having begun preproduction with longtime collaborator Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, ASC, AMC. “It boiled down to time,” Cuarón explains by phone from a family trip in Italy. “I was going to have a long prep, shooting schedule and DI process. Then I decided to give us even more prep time, and we realized we also would need more shooting time. Chivo said, ‘This is not going to work for me anymore, because I have other commitments.’ So, we had a discussion about him starting the shoot and I’d find someone to do the rest, but we realized that [wouldn’t be] best. I wanted one eye all the way through.”

He talked to several other cinematographers, but didn’t end up using them, and he concluded that on a movie tracing his roots, it was important that he speak his native language of Spanish on the set. “That’s when Chivo said, ‘Stop fooling around. You should do it,’” Cuarón recalls. “I realized it was necessary for the process, because it was such intimate stuff I was doing — bringing images from my own memory.”

Cuarón was no stranger to the job, having spent more time as cinematographer than director in film school and early TV projects, such as the 1980s horror anthology series Hora Marcada (to which Lubezki contributed his talents as well). He has also performed additional shooting on some of his recent features.

He spent about six months in hard prep, knowing from the start that he wanted his movie to be in black-and-white. He and Lubezki, who shot Gravity largely on Arri’s Alexa Classic, tested various film and digital cameras, narrowing their options to Arri’s Alexa XT B+W — which has a modified monochromatic sensor — or shooting in color on Arri’s Alexa 65 and then desaturating in post.

“I wanted a digital black-and-white,” Cuarón elaborates. “I wanted a film shot today in black-and-white, and looking into the past. I would refrain from that classic, stylized look with long shadows and high contrast, and go into a more naturalistic black-and-white. I didn’t want to try to hide digital in a ‘cinematic’ look, but rather explore a digital look and embrace the present. Each media — celluloid and digital — has its own language and its pros and cons, but I wanted to explore the amazing dynamic range of the digital form.”

Lubezki ultimately pushed him toward the Alexa 65. “I was skeptical about the large format, but the 65’s dynamic range was unbeatable,” Cuarón says. “And as we did tests, I realized this movie is honoring real-time and space, and here we would have a larger scope in which the characters could flow. I wanted to shoot very wide, and balance foreground and background with each informing the other. The characters are a part of society, and society is made up of individuals.”

“I didn’t want to have even the notion of color in the process, including location-scouting and casting. Everybody was required to deliver their files in black-and-white.”

He shot at 6560x3100 resolution in Open Gate mode at 24 fps, capturing to 2TB Codex SXR Capture Drives. The movie is presented in the 2.39:1 aspect ratio, and Cuarón usually framed to allow for an extra 4 percent of space to be able to further stabilize the image. Ernesto Joven handled DIT duties.

The production borrowed Lubezki’s show LUT from Birdman (AC Dec. ’14) and The Revenant (AC Jan. ’16), both of which the director of photography shot for Alejandro G. Iñárritu. “This allowed us to target and key red, green and blue values to control and manipulate parts of the image,” says Technicolor senior finishing producer Michael Dillon.

“That was part of Chivo’s [contribution],” Cuarón adds. “In color, you take advantage of the whole dynamic range. Chivo’s LUT allows some contrast and the color tends to be desaturated, [yielding what] I would [call] a ‘melancholic naturalism’ — but in black-and-white, and adding a bit of contrast, I would characterize it as a ‘soft naturalism.’”

Both Lubezki’s original LUT and the modified LUT for Roma were authored by ASC associate member and Technicolor vice president of imaging research and development Joshua Pines, who notes, “The source timeline was OpenEXR linear files in Arri wide-gamut color space. A linear-to-log (Log C) transform was applied on input to the color corrector. Creative grading was done in this log space. Color information was available, which could assist with keying for color correction and visual effects. A custom final-output rendering transform provided an overall creative look for the movie, in addition to desaturating the image to black-and-white.”

On each side of the screen, they placed an additional smaller panel playing a fraction of the movie frame to wrap the light a bit more. These panels were erased in post. “We were fighting with concert venues to get enough LED panels for that day,” Cuarón recalls.

Although originating in color, Cuarón insisted on looking at only monochromatic images unless absolutely necessary. “I didn’t want to have even the notion of color in the process, including location-scouting and casting,” he says. “Everybody was required to deliver their files in black-and-white.”

Cuarón paired the camera with Arri Prime 65 lenses, which he calls “fantastic.” He adds, “The downside was that I wouldn’t reach the sweet spot of the lens until T4.5 to T5.6. Before that, they would be soft and break up a little bit, and edges would be more noticeable. Because of the format, the edges tend to distort when you work with lenses as wide as ours. For more than 10 years I’ve been working in spherical 35mm [format], and only with 18mm and 21mm [lenses], and here with the Alexa 65, we worked with the roughly equivalent 35mm and 50mm.”

Cuarón eschewed lens filters other than NDs. “For interiors and big spaces, I decided not to use any smoke or equivalents,” he adds. “That creates a beautiful diffusion for the background, but I refused to use it unless it was absolutely justified, as I wanted a very sharp and grainless look.”

Shooting spanned early fall of 2016 to the following spring, encompassing more than 110 days of principal photography.

Capturing in color also allowed the production to work with greenscreens, as in a scene in which Cleo crosses an avenue after a family night out at the movies, when the kids think they spot their father and his girlfriend. The production made every effort to shoot on the locations where events actually transpired, but in this case the actual street had changed so much since the 1970s that Cuarón had production designer Eugenio Caballero construct an enormous six-block-long set in an industrial space.

“We had to be careful of the contrast of different colors — which look great to the naked eye, but when translated in [gray] tones were a single one-tone block.”

Working from photos of the era, the art department painstakingly re-created period-accurate details, right down to the goods for sale in dress and camera shops. Gaffer Javier Enríquez and his team lit the stores with various practicals amplified by diffused LiteTile+ Plus 8 foldable LED fixtures, as well as 5K tungsten lights and 10K Fresnels. “The diffusion we could get from the equipment rental houses [was] not thick enough to diffuse these fixtures, so I went to look for a regular fabric,” Enríquez notes. “After I found the appropriate fabric, it was sewn [to] the measurements we needed. In addition to these, [we also used] regular gray fabrics, which were bought locally, to create volume and direction to the light.”

A 20'x20' cube constructed with diffusion frames housed three 18K Fresnels and was hung from a crane over the intersection, surrounded by bounces to simulate the light from the cinema marquee. They also placed 18Ks on rooftops. “We used all the 18Ks in Mexico,” Cuarón quips. Greenscreen was placed at one end of the strip for CG street extension.

“I thought, ‘My God, we’re doing a movie like in the 1950s,’ with a huge camera and a lot of light.”

Cuarón’s actual childhood house had also changed too much to be used — so, relying on family photos, the production re-created it using a similar house that was scheduled for demolition, which allowed Caballero to construct a wild-walled set within the residence. The art department decorated the location with whatever original furniture and personal items Cuarón could procure from his family. The filmmakers occasionally ‘cheated’ colors in the set design and costume designer Anna Terrazas’ period clothing, depending on how they registered in black-and-white.

“A certain range of reds and blues would go dark quickly,” Cuarón notes. “Sometimes it was about translating a color separately. For instance, I wanted all the tiles in the house to be the original colors. The original floor tiles were yellowish but they were translating too bright, so we wound up using a greenish color. I felt uncomfortable seeing a color that was not right at first, but it translated beautifully into black-and-white. Also, we had to be careful of the contrast of different colors — which look great to the naked eye, but when translated in [gray] tones were a single one-tone block.”

Equipment got tied up at customs, so Cuarón didn’t have time to test the Alexa 65 in the family home, the movie’s main location. By the time they got rolling, he was surprised by how much lighting was required to shoot at T5.6. “I thought, ‘My God, we’re doing a movie like in the 1950s,’ with a huge camera and a lot of light,” Cuarón says. “Also, I didn’t want long, stylized shafts of light. I wanted naturalistic soft-light sources, but we were shooting very wide, seeing the extension of the house from one corner of the house — seeing everything. It took a lot of light with bounces and diffusions to go through the windows and get enough exposure deep into the rooms.”

Since movie lights were hard to hide, Enríquez’s staff relied on Arrimax 18s outside windows as a daylight source. Additionally, they rigged on the roof an 8'x6' mirror that reflected sunlight down through a skylight, sometimes through muslin. This would be amplified by a custom-made version of a space light — also on the roof — comprised of a metal-framed cylinder containing three Arri M90s pointing up at bounce material.

For night interiors, the production used practicals including a chandelier containing a 1K bulb that could be raised and lowered above the staircase, with LiteTile+ Plus 8 wrapped high around the wall for fill. Enríquez also hung a 20K in a cylinder that was blacked-out except for its diffused bottom, with skirting further directing the light downward. Enríquez notes that the bottom was diffused with “three layers of diffusion. One was white fabric, bought locally, and the other two were Chimera Full.” If any lights appeared in frame, they were erased in post.

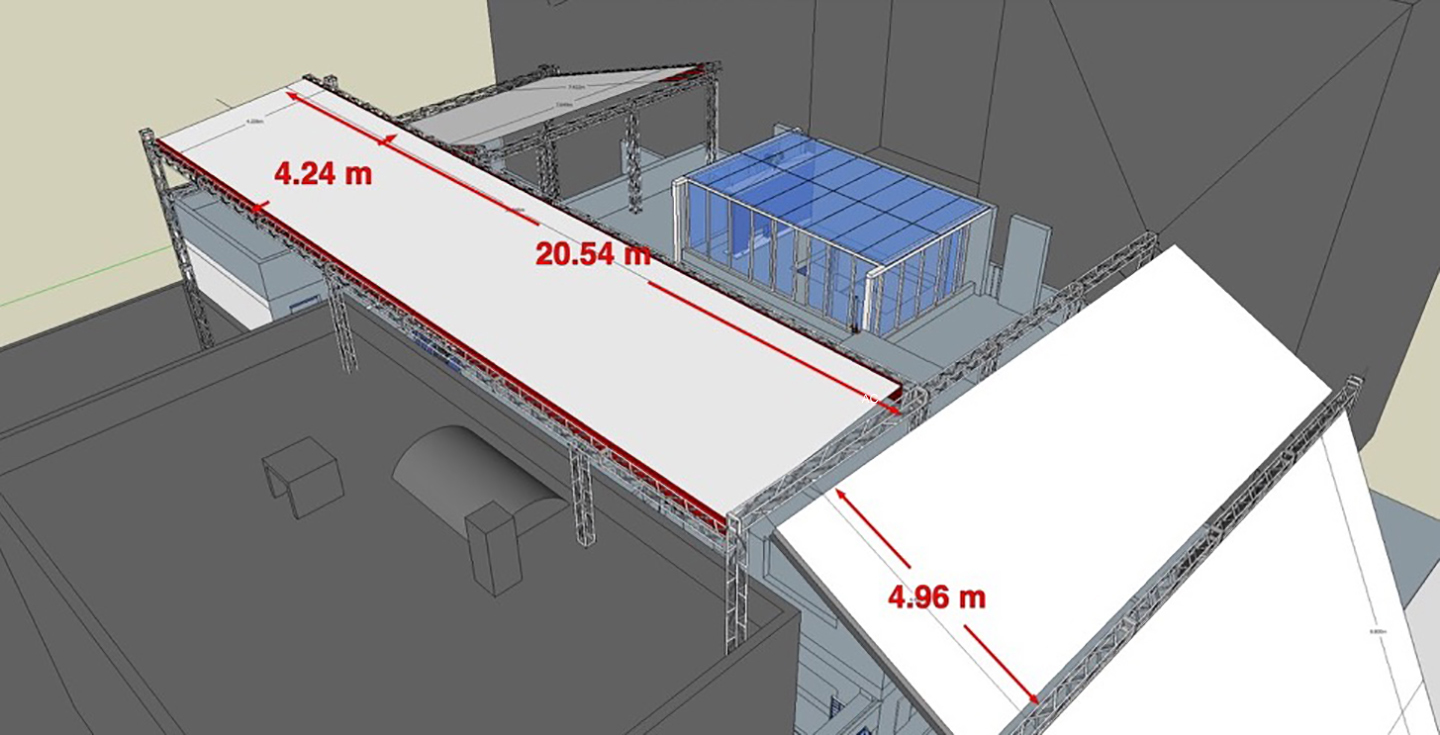

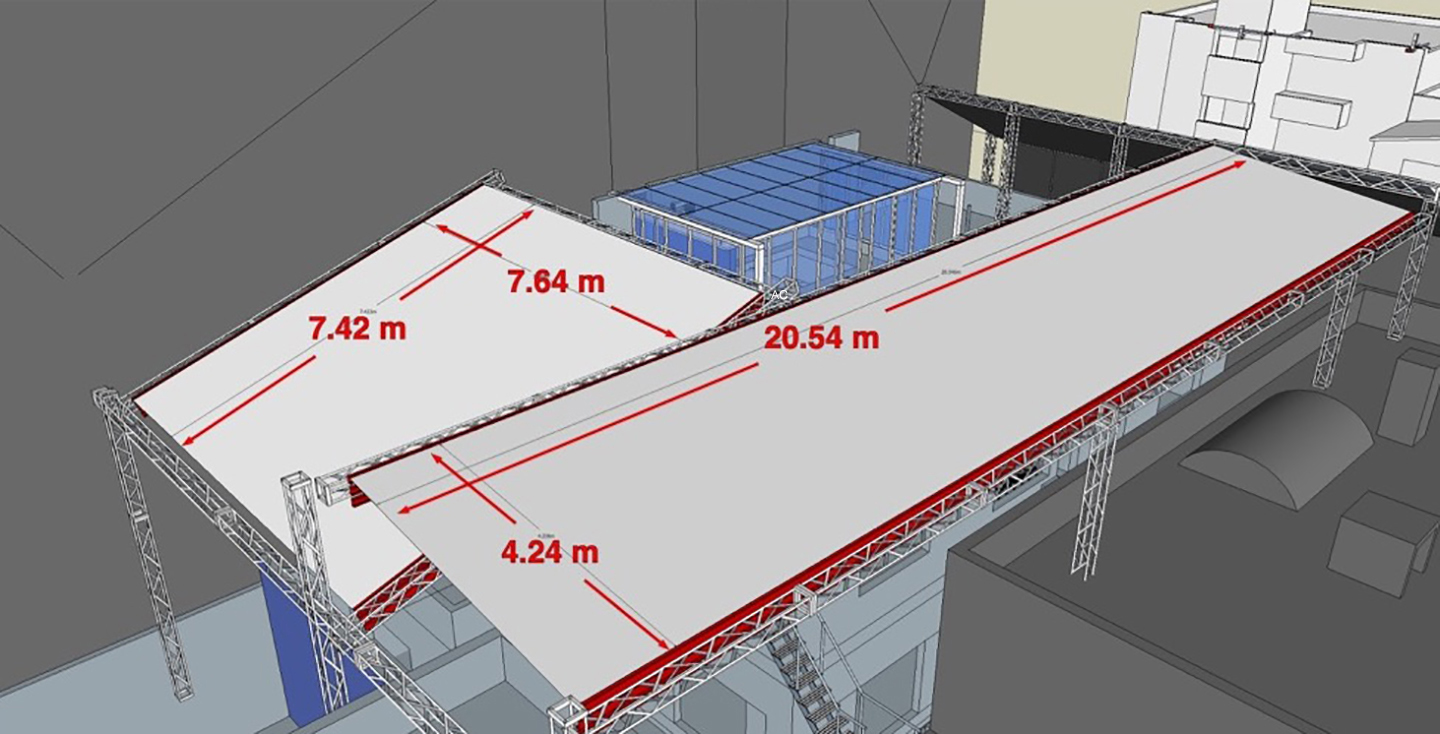

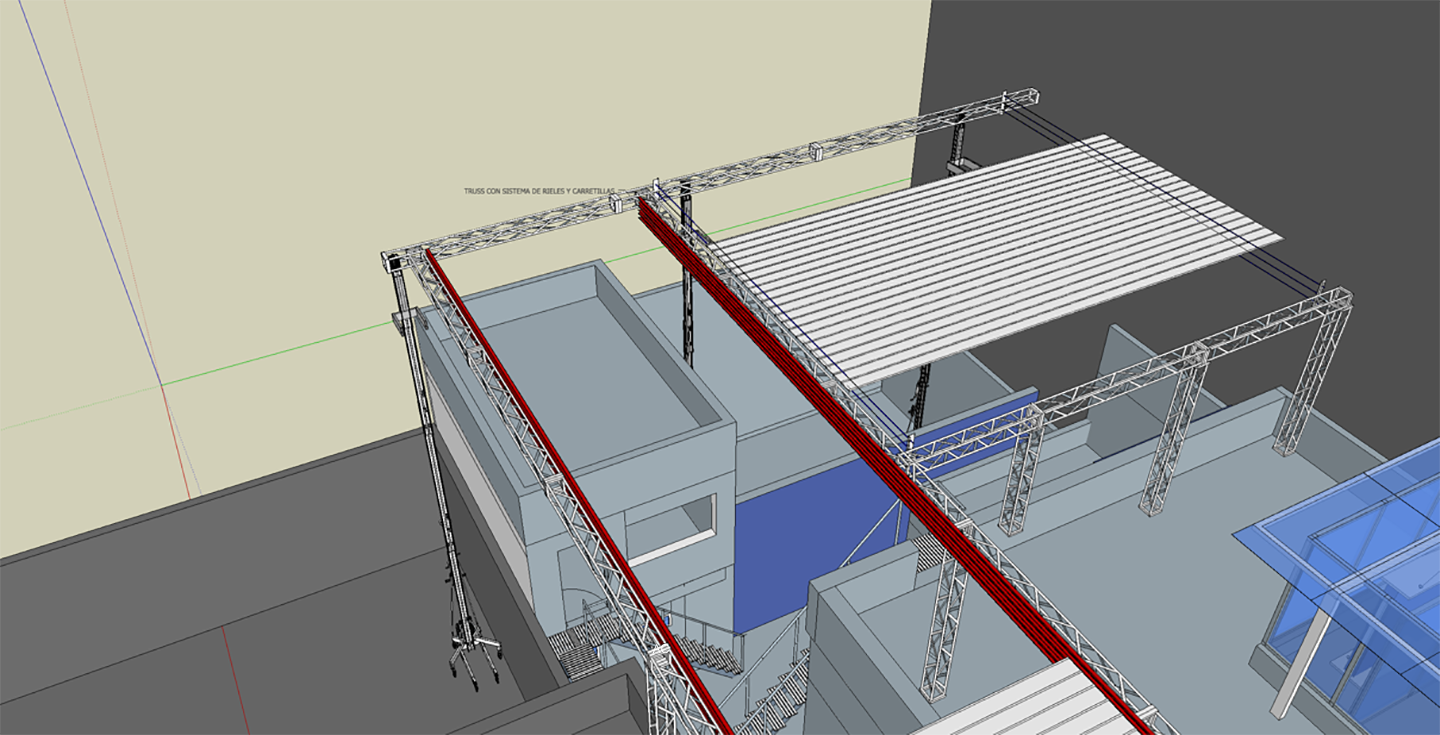

A massive mechanized rail system was built over the top of the house that enabled a curtain-like extension of black fabric for contrast and day-for-night shots, as well as three layers of soft diffusion — comprising the same material as had been employed with the aforementioned cylinder-housed 20K — for varying amounts of sunlight. Three sides of the building were covered this way, with the largest extension measuring 67'x14'. “After my first meeting with Alfonso, and understanding what he wanted to do, I started designing [a way to make this possible], and I came up with this mechanized rail system,” Enríquez notes, “It took about one month of prep designing and [constructing] it with my technicians.”

“It was a location that worked like a studio.”

“A couple of times we wanted the light to change within the shot, which we could do by sliding [one of the fabrics],” Cuarón says. “It was a location that worked like a studio.”

The exterior of the house, Cuarón relates, “was shot across the street from the original house, because that house had the same configuration as our interior set, [with the] patio on the left and the house on the right — [which was] the mirror image of the original house.” In addition, he says, “this way we would face south when photographing it, and the sun would, at the right hour, backlight the ground glass of the gate.”

Galo Olivares operated the A camera, while Cuarón was responsible for the actors, for setting the camera angles and movements, for the look, and for controlling the aperture. Cuarón stood by his calibrated Flanders Scientific CM250 monitor when they were rolling. “Galo is a DoP in his own right, and a great camera operator,” the director says. “It was a privilege to have a young, fresh eye near me. Sometimes he would look at me and say, ‘Are you sure you don’t want a negative fill?’ And I would say, ‘You’re right — negative fill.’”

The B camera, operated by Alejandro Chávez, only occasionally came into play. One such sequence involved a picnic in which the adults show their proclivity for recklessly firing guns. Within this is a sequence in which children, including a boy costumed as an astronaut, and dogs run through a pondy forest. Using the two cameras — one on a Technocrane and the other on a tripod — ensured “being able to have the sunlight in the perfect position for the two shots,” Cuarón says, “and also the perfect continuity” when cutting between the two angles.

“Sometimes you are tempted with amazing angles, but you know you have to do only the one that is right.”

The single-camera approach gives the movie a consistent perspective, one in which the camera is unobtrusive — Cuarón characterizes it as “objective” — and usually on a dolly, sometimes with a Scorpio Stabilized Head or Libra remote head. There are no handheld or Steadicam shots, as those, the director says, “would change the language we were after.” Cranes were sometimes employed, but as with the dolly, there were no moves in and out — only panning and tracking.

The Corpus Christi massacre was the project’s most logistically complicated sequence. Cuarón, of course, elected to shoot it at the very intersection where the tragedy unfolded. Hundreds of extras, stunt performers and period cars were brought in following extensive rehearsals on a football field. The production had initially requested that the location — which is currently a busy part of town — be shut down for three days, though they left after only two, believing they had caused enough disruption.

On-hand city officials were reportedly surprised when they saw that the sequence’s most expansive shot was captured by only one camera from behind a second-floor window. In the scene, Sofía’s mother, Teresa (Verónica García), brings the pregnant Cleo to a furniture store to buy a crib, just as the mayhem begins outside. Shop patrons rush to the window and the camera pans from them to reveal protesters and paramilitary forces clashing on the street below.

“Sometimes you are tempted with amazing angles, but you know you have to do only the one that is right,” Cuarón explains. “Part of our approach was to extend every shot through to its natural consequence, and not do long shots just for the ‘Olympics’ of it. I decided to cut from that shot before it calls attention to itself.”

In the store location, the crew placed about 60 Kino Flo tubes in the existing fluorescent fixtures, and also took advantage of the light from practical lamps ostensibly being sold in the store.

“We needed a lot of light to get the necessary interior exposure while being able to see outside without overexposing,” Enríquez notes. “Also, behind the windows we hid Maxi-Brutes to create a sense of sunlight entering the store. That was one of the few scenes in which we used direct light, since it was a day interior with windows in the shot, and it added a dramatic element. Outside, we used mirrors of different shapes to cast a strong light on some background actors, such as police officers and running students.”

The crew shot at a time of day in which the sun through the back windows provided ambience as well as a hard backlight on the characters as they enter the store. When they captured the crowds on the other side, however, the building blocked the sun, providing a less contrasty look below.

With the camera panning from the interior of the store to the window, Cuarón had to be particularly nimble in manipulating the aperture. “As we go to the window, we went down three stops, and then three stops up as we go [back] inside,” he says. “I tried to do it as subtly as possible. It was a constant in our longer shots: When the sun appears, make big stop changes.”

Cuarón was heavily involved in the final-grade process, and worked in Hollywood with Technicolor supervising finishing artist and ASC associate member Steven J. Scott. According to Cuarón, the sessions comprised 576 hours of color correction and 397 hours of additional color support, for a total of 973 hours of sessions spread over six months. Scott, a longtime collaborator, had been involved in the discussion of the look since the camera-testing phase with Lubezki. Finishing was performed in 4K with 16-bit open float linearized Log C EXR files, using Autodesk Lustre/Flame 2019 Connected Colour Workflow software on Lenovo ThinkStation P920 machines.

The display LUT converted the full-color image to black-and-white. Having the color information available throughout the finishing process allowed for greater control in manipulating elements of the image. “If Alfonso had shot in black-and-white,” Scott explains, “and if you had somebody wearing a pink sweater against a light-blue sky that matched the tonal range of that pink sweater, we would have had two similar shades of gray and wouldn’t have been able to isolate either one. But with the color intact, I could use all of the color range in my Lustre, which meant I could isolate and manipulate that pink without affecting the sky. Although you don’t see the color, it gave us a much broader range of options in terms of what we could isolate and manipulate. For practical reasons, Alfonso’s decision to shoot in color was brilliant.”

Scott also used Flame to deal with tricky lighting situations. He analyzed and created luminance curves that would read light-level fluctuations, and then used those curves in Lustre to organically and automatically compensate with brightening corrections when a shot flickered dark. This came in handy for the beach, forest-fire and cinema-interior scenes where there were extreme lighting fluctuations. “That was the biggest innovation for me,” Scott relates. “Alfonso inspires me to think expansively because of the unique demands of the beautiful images he captures. He always keeps me on my toes in the best possible way.”

Standard dynamic range (SDR) and then extended dynamic range (EDR) passes were completed separately, with Cuarón finishing them differently to take advantage of the unique characteristics of each. “I want to look into the shadows and see everything I possibly can,” Scott says. “That’s the great thing about EDR, and the Dolby Vision [projection system] in particular. Because the low- and high-end information is not visible with SDR, if you put black on the screen, it’s going to appear dark gray. But if you put black on an EDR screen, it’s an absolute, beautiful black. There can be a lot of layered information in that range from SDR black — [or] gray — to absolute EDR black, and we tried to reveal as much of that detail as possible in the EDR pass. We had the same goal for the high end — to show details in the clouds, sky and even the sun that SDR couldn’t begin to approach.”

children, however, Cleo must go back as a couple of the kids go in over their heads in the choppy waves. Although she can’t swim, she wastes no time braving the surf to

try to get to them. The camera tracks with her along the beach, from sun to shade to sun again, following her right into the water.

Cuarón reports that delivering a single IMF master file to Netflix that contained the HDR master along with the SDR “trim pass” metadata wouldn't reproduce or stream the SDR image as it was originally conceived during the finishing process. Therefore, for the first time, two separate IMF files were delivered to Netflix. Cuarón notes, “This was very different from the standard Netflix delivery of only one IMF file that included the HDR pass along with SDR trim metadata. The Roma package included both an HDR file, as well as a separate and distinct SDR file. This allowed us to take full advantage of all of the original Lustre tools to time both the HDR and the SDR separately.” The first IMF master served HDR clients, the color grade for which was based on the DCI XYZ master, but was extensively adjusted in Lustre to optimize it for HDR. The second IMF master served the SDR clients, the color grade for which was also based on the DCI XYZ master, “but it was carefully adjusted by Steve Scott using all of the Lustre tools originally available in the SDR color-grade suite, and not just the more limited SDR trim tools available with the Dolby Vision toolset,” Cuarón offers.

On his choice to shoot as well as direct, Cuarón confirms that he would do it again. “In a second,” he says. “I think I will drift back and forth, because I also enjoy the collaboration with cinematographers I admire. I like learning from them. Talking about not only their technical approach but also their conceptual approach is so much fun. I started as a cinematographer, and, after all these years, to take it from the beginning all the way to postproduction was just a joy.”

Cuarón earned an ASC Award nomination for his outstanding camerawork and took home the Academy Award for Best Cinematography.