Royal Rumble - Godzilla: King of the Monsters

Mothra, Rodan and King Ghidorah join this kaiju melee directed by Michael Dougherty and shot by Lawrence Sher, ASC.

Mothra, Rodan and King Ghidorah join this kaiju melee directed by Michael Dougherty and shot by Lawrence Sher, ASC.

Unit photography by Daniel C. McFadden and Wallace Michael Chrouch. All images courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures.

He’s back, he’s angry, and he’s got company.

In Godzilla: King of the Monsters, human actions trigger the reappearance of the titular “Titan,” who was last seen returning to the sea after saving San Francisco. But other legendary monsters also have been roused — the insect-like Mothra, the pteranodon Rodan, and the three-headed dragon King Ghidorah — each of whom is devastatingly powerful. As these behemoths vie for supremacy, the human world becomes collateral damage.

The Monarch organization, which has long tracked the beasts, hopes to contain the threat. Dr. Emma Russell (Vera Farmiga) has developed technology to communicate with — and potentially control — the Titans. While she seeks a peaceful resolution, her ex-husband, Dr. Mark Russell (Kyle Chandler), has personal reasons for a more hawkish approach. First, though, he must rescue Emma and their teenage daughter Madison (Millie Bobby Brown) from a shady group with its own agenda.

Director Michael Dougherty describes himself as a lifelong fan of the franchise, and he relished the opportunity to make what he calls his “dream Godzilla movie.” Though King of the Monsters continues the story from 2014’s Godzilla — directed by Gareth Edwards and shot by Seamus McGarvey, ASC, BSC (AC June ’14) — Dougherty strove to give audiences something different. “We had to up our game,” says Dougherty, who co-wrote the script with Zach Shields. “One of the rules of sequels is to go a bit bigger and bolder with each chapter. Thankfully we have four giant monsters, so it was easy to go bigger.”

King of the Monsters marks the first collaboration between Dougherty and cinematographer Lawrence Sher, ASC. Sher came to the project following his directorial debut, the feature comedy Father Figures. “That was an incredible experience that I enjoyed immensely,” Sher says. “Directing made me feel inspired again to shoot — and to shoot something challenging and different then I had done before.”

Specifically, Sher was looking to dive into blockbuster action after having built a cinematography résumé that was dominated by comedies such as The Hangover and its two sequels. He knew that making the transition might take some convincing, but working in his favor was the additional photography he did on the 2014 Godzilla. “That was a good experience, and it dipped my feet into that world,” Sher reflects. “Perhaps it also allowed [producer] Mary Parent to see that I could shoot this movie. Most cinematographers believe they can do any genre, but on a big sci-fi action movie, it’s tricky to get people to take a chance on someone who hasn’t shot one before and isn’t the obvious choice.”

Sher quickly won over Dougherty. “He came in with a look book of frames from films — some sci-fi, some not — that he felt captured what this movie could look like,” the director recalls. “I had already collected some of the same ones. It was one of those eerie moments of synchronicity, when you feel a connection right away. We spoke the same visual language, and I knew we would see eye to eye.”

Blade Runner (AC June ’82) was a prominent reference. “That’s a gorgeous science-fiction film, never surpassed in terms of aesthetics,” the director says. Alien (AC Aug. ’79) was also an influence, as were its sequels Aliens and Alien3 (AC Dec. ’92). “There is a moody and grounded quality in those films that we wanted to bring back,” Dougherty continues. “Those filmmakers weren’t afraid of shadows and grain. I miss the atmospherics and texture of those films. As we start to embrace digital, I worry the image is getting too clean and perfect all the time, which takes away from the tension you can build with darkness and shadow and splashes of light.”

The filmmakers also carried forward visual elements from the previous Godzilla. “We liked how [Edwards and his collaborators] created a universe that felt real and kept the movie on ground level as much as possible,” Sher notes. “We wanted to carry on that tradition and make the audience feel it’s participating in the movie, and to convey how unbelievable it would be to live in a world with these monsters. We also wanted to introduce more dynamic color, and we found inspiration in science-fiction movies of the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s that had a very real and dirty look. We had atmosphere in nearly every set.”

Despite Dougherty’s concerns regarding overly crisp images, the filmmakers opted to shoot digitally. They considered Arri’s Alexa XT Studio camera, but Sher believed the greater resolution of the large-format Alexa 65 system would better serve the big-scale, effects-heavy movie, which was destined for IMAX screens. The producers agreed.

In keeping with the last Godzilla — as well as Kong: Skull Island, which exists in the same onscreen universe and shot by Larry Fong, ASC — the production elected to work primarily with anamorphic lenses, though the filmmakers recognized that certain visual-effects shots would benefit from being shot with spherical lenses. “Mike and I love the anamorphic look in Alien and Close Encounters of the Third Kind [AC Jan.’78], and we wanted the feel of [anamorphic’s] dirty imperfections,” Sher explains. “We would go spherical to use more of the sensor for visual-effects shots that we knew we would have to reposition, or extend at the top or bottom, and to have a little less anamorphic distortion. The Alexa 65 gave us more image resolution, and when we went spherical it gave us even more image quality.”

The lens package included Panavision C Series, E Series, G Series and T Series anamorphic primes, as well as a 150mm anamorphic Macro Auto Panatar. For certain long-lens shots the crew also carried Nikon Nikkor 300mm and 400mm spherical primes with rear anamorphic adapters; once or twice, Sher estimates, the 300mm was also paired with a 1.4x extender. “We stuck mostly with primes for 90 to 95 percent of the movie,” Sher notes. “Philosophically, we were trying to be close to the actors to keep an intimate and ‘immediate’ relationship. The C 60mm became a much-used lens for us because it had a close-focus of 19 inches, which made it useful for extreme close-ups and handheld [shots].” He adds that the C Series 40mm was another workhorse lens.

The crew always ran two cameras — A camera was operated by Christopher TJ McGuire, and B was operated by Thomas Lappin — with a third camera added approximately a quarter of the time; Panavision ATZ 70-200mm (T3.5) and ALZ10 42-425mm (T4.5) anamorphic zooms came into play on C camera for select day exteriors. For spherical shooting, the crew used a set of Panavision Primo 70s ranging from 14mm to 80mm. In all cases, the filmmakers framed for a 2.39:1 aspect ratio.

Sher would often shoot at T2.8, and to arrive at that in big night exteriors, he would sometimes raise the camera’s exposure index to 1,600 or 2,000, as in a sequence in which monsters clash at Boston’s Fenway Park. The production built a replica of part of the stadium’s famous “Green Monster” left-field wall and surrounded it with bluescreen, then re-created the rest of the environment with plates and CGI set extensions.

“When we knew we needed more depth of field for the creatures, we would bump up to T4 or T5.6,” Sher adds. “We didn’t want a lot of mushiness in the background — in the large format, that can make it feel strained. What might otherwise look out of focus and beautiful at T1.4 or T2 might make the creatures look less real because of their size and proximity to the lens.”

For Steadicam moves in close quarters — such as those in an Osprey military-aircraft interior set and a submarine interior set — the filmmakers would sometimes switch to Arri’s Alexa Mini camera. “We also had various security-camera and body-camera shots, for which we used Sony a7 cameras and actual police body cameras,” adds DIT Nicholas Kay. “They all shoot 30 fps, so we had to convert the footage.”

Principal photography spanned June to late September 2017 and took place in and around Atlanta, Ga., with sets constructed at Blackhall Studios and at an OFS Optics warehouse facility that has been retrofitted for production.

Most scenes required a tremendous amount of interactive light to suggest the atomic bioluminescence of the Titans, each of which emits its own distinguishing palette: blue for Godzilla, red for Rodan, yellow for King Ghidorah, and a mix of pastel yellow and blue for Mothra. The colors were CG-animated as part of the creatures, but also needed to play on the live-action human characters and the physical environments.

In an early scene, for example, Emma and Madison are at a research station that Monarch has established in a Chinese mountain temple to monitor Mothra’s cordoned-off cocoon. Production designer Scott Chambliss’ team built a huge set, in Blackhall Studios’ Stage 9, that encompassed a control room, a decontamination chamber, and a footbridge to a circular walkway from which the cryptozoologists look in on the cocoon; the rest of the environment was created with the aid of a 425' bluescreen that ran along the perimeter. As Mothra hatches, her colors burst forth, varying with her mood. Monarch’s electric-shock jabs anger the Titan and push her light emission into hotter reds and yellows. Emma uses her device to calm the creature, whose color display shifts into a slower-moving kaleidoscope of cooler hues.

The production would roll through the entire five-minute sequence, with the moving and changing lights controlled by console programmer Elton James and gaffer Dan Cornwall on an expanded High End Systems Hog 4 lighting console. The bioluminescence was created with video content that was fed into a series of Roe Visual’s Hybrid LED panels that were arrayed out to 30'x8' and positioned on Pettibone telehandlers on opposite sides of the room.

The bioluminescent video content here and elsewhere throughout the movie was sourced from images of railroad worms, comb jellies, fireflies and the aurora borealis. The panels were often suspended on cranes and could be fed video of the monsters — sometimes sourced from previs, and at other times with images of previous iterations of the monsters that James found online — to help with the actors’ eyelines and performances, in addition to directly illuminating the actors and working in concert with a scene’s “movie” lights.

“A fireball across that screen will give you a great exploding fire source,” Cornwall notes. “We used the panels for lighting when driving in vehicles, flying in aircraft, and for monsters coming at actors. And Elton could map any fixture so that when the light from the video ran across that [portion of the] map, it would illuminate [the fixture accordingly].”

“If it wasn’t the bioluminescent effect of monsters, it was flickering lights or emergency beacons that we were creating,” Sher adds. “We needed to have interactive lighting to represent storms — most of the movie takes place in storms — as well as the monsters fighting.”

James’ mapping would guide the color and intensity of, among other fixtures, Arri SkyPanel S60-Cs rigged on condors as well as Martin Atomic 3000 LED units that provided a strobe effect. The live sequencing of such lighting cues could be recorded and reused for subsequent takes; according to Cornwall, the movie required more than 12,000 cues, whereas an average blockbuster might need 500.

Around Mothra’s cocoon, 35 hanging Kino Flo Image 87s and the same number on the floor were directed at the bluescreen, while Sourcemaker RGBH LED Blankets keyed the actors. A dozen Digital Sputnik LED units provided light that represented a decontamination process, while GLP Impression X4 and X4 Ls contributed to Mothra’s colorations and to red emergency lighting. For a shot in which Madison reaches out to touch Mothra while the creature is in its larval form, light from the monster’s head was created by a Chimera Pancake Lantern outfitted with pulsating, color-changing Sourcemaker LED Ribbon, which set-lighting technician Kyle Morgan directed on an extension pole toward Brown.

Interactive lighting was also employed for a scene set in a Monarch ocean base, from which Godzilla’s movements are tracked through a huge underwater window. The observers see the monster approaching — his bioluminescence serves as a beacon in the murky waters — but are unsure whether he comes as friend or foe. When the monster arrives, he generates a massive amount of light as part of a display of intimidation.

This set was built at the OFS warehouse, and much of the room was lit by computer monitors, accent lights and architectural fixtures; Sher credits fixtures foreman Phillip Abeyta with rigging the many dimmable practicals. The crew also tucked LED fixtures and ribbon where they could, and they kept movie lights off the ground to enable shooting in 360 degrees. The scene opens with McGuire’s 40-second Steadicam shot, which brings the scientists into their positions in the space.

During preproduction, Company 3 senior colorist and ASC associate member Jill Bogdanowicz came to Atlanta to help create the show LUT and make sure everyone was on the same page. As Sher wouldn’t be around for all of post, he was comforted to have Bogdanowicz step aboard early on; the duo had worked together on four previous features. Plus, Bogdanowicz was particularly well-versed in the filmmakers’ Blade Runner reference, having worked on that film’s digital restoration.

On set, Sher collaborated with DIT Kay on a first-pass grade, using the show LUT as a base. They worked on Barco RHDM-2301 monitors set to P3 color space and calibrated to match the Barco cinema projectors used by EFilm dailies colorist Ben Estrada. Sher used the eVue platform from EC3, the dailies unit for EFilm and Company 3, to evaluate dailies.

Bogdanowicz performed the final grade at Company 3 in Santa Monica, with Dougherty sometimes in the room and sometimes participating remotely. Four weeks were spent on the 2D theatrical version, working with EXR files in Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve 15 running on Linux hardware. Bogdanowicz added grain to further realize the filmmaker’s desired look.

She says the monsters’ colors were among the grade’s top priorities. “They all have subtle skin colors, and they’re in a lot of different environments, such as Antarctica with the cold, blue ice. And then there’s fire and explosions and a lot of atmosphere, so we made sure their skin colors stayed consistent and worked well within those environments. We also tweaked the visual effects as they came in, to make sure they flowed together.”

Throughout the grade, Sher chimed in remotely as time permitted from Company 3’s facility in New York; he was in the Big Apple shooting Joker, the Batman villain’s standalone feature helmed by Hangover director Todd Phillips. Slated for release later this year and coming on the heels of Godzilla: King of the Monsters, Joker promises to be another bold statement about the breadth of Sher’s abilities. “King of the Monsters was a great opportunity for me to put my stamp on a big science-fiction movie,” the cinematographer reflects. “It’s been a really good stretch for me to go deeper into cinematography and work on getting better at what I do.”

Jazz Improvisation

Throughout production on Godzilla: King of the Monsters, the camera was often placed on a Technocrane under the care of A dolly grip Alan “Moose” Shultz and Technocrane operator Jason Talbert. “We played jazz,” cinematographer Lawrence Sher, ASC describes. “We would run the scene complete from top to bottom without rehearsals or marks. I communicated with them on HME headsets, and we would just watch the actors and improvise moves in real time, creating dozens of individual shots that ended up in the movie — small camera moves, huge wraparounds, big reveals, and push-ins into close-ups. Then we’d do another full take and try an entirely different series of camera moves, making close-ups and push-ins to other people in the scene, capturing new pieces of coverage. Because of the skills of those two, and of 1st AC Gregory Irwin on focus, we were allowed the freedom to constantly move the camera and not ever feel like the technical was compromising the creative.

“We did this for many scenes in the movie, whether on a 50-foot Techno, 30-foot Techno, or traditional dolly track on dance floor,” Sher continues. “It was like being able to do Steadicam or even handheld masters, but on a Technocrane. Our Libra tech, Aaron York, recommended using this HH attachment that allowed the Libra controls to be placed on a shoulder and operated like a handheld camera. That gave us the ability to combine the feel of handheld and even high-frequency camera shake with the precision and mobility of a crane in ways that an operator [with a camera] on the shoulder or sled couldn’t do — things like super-low-mode and rising to 20 feet, or craning over the seats on the control deck of our huge stealth-bomber set [see below], or fire or other obstacles on the ground.”

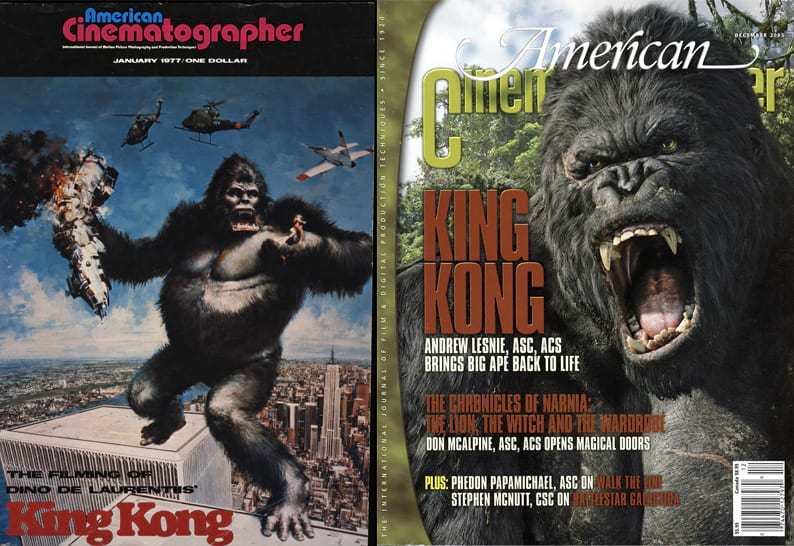

Legendary's Godzilla will next been seen on the big screen when he faces off against the aforementioned King of Skull Island in Godzilla vs. Kong (coming in 2020). Before then, take a look back at some of Kong's biggest moments from the past in AC Jan. ’77 and AC Dec. ’05.

[Left] Peter Jackson's King Kong (2005), shot by Andrew Lesnie, ASC, ACS.