Saltburn: Weaving a Web of Obsession

Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF and writer-director Emerald Fennell’s Gothic drama explores the dark corners of an aristocratic estate, where a strange loner goes on holiday.

Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF says “gorgeous” was writer-director Emerald Fennell ’s favorite word during the filming of Saltburn. Gorgeous, but with a twist. “Emerald loves things that are gorgeous and ugly at the same time,” Sandgren says. Fennell corroborates: “Everything had to have a bit of roughness, a bit of ugliness. Part of something being perfect for this film meant that it was not completely perfect.”

Setting the Obscene

Saltburn, a darkly comedic Gothic drama, is set in the U.K. of the early 2000s. The story follows lonely Oxford student Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) as he befriends Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi), a charismatic, upper-crust classmate. Felix invites Oliver to spend a summer at his sprawling estate with his impossibly wealthy, aristocratic family (mum and dad are played by Rosamund Pike and Richard E. Grant). From there, the film takes a wicked turn, weaving a web of obsession, privilege, sex, lies and taboos.

The filmmakers set out to ensnare the viewer with stunning imagery. “Because it’s beautiful,” Sandgren says, “the viewer becomes intrigued, but then sees things that are really quite disturbing.” Juxtaposing the beautiful with the grotesque, and the beguiling with the appalling, was essential to developing the look of the film. “We wanted to create this internal struggle, where you like what you see but you also don’t like it, or maybe you feel bad for liking it,” Sandgren says.

“They’re similar in that way to old-school horror movies and early Hitchcock films, which were also important references.”

— Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF

Fennell, an actor-turned-writer-director whose directorial debut, Promising Young Woman, earned her an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay in 2021, brought Sandgren a vast catalogue of images to help visualize the feeling of Saltburn. Sandgren had Fennell break down the film’s tone into a series of evocative words and phrases, and then developed a series of collages for its many setups and moods. Sandgren pulled film stills from A Room with a View (for sunny exteriors on the mansion’s grounds) and In the Mood for Love (for moody night interiors), as well as paintings by 18th-century British artist Thomas Gainsborough. Baroque paintings by artists like Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi also became major touchstones. “They are often quite obscene in their themes, and the lighting is often overly dramatic compared to reality,” Sandgren says. “They’re similar in that way to old-school horror movies and early Hitchcock films, which were also important references.”

Framing an Artificial World

The film was shot primarily in Radcliffe Square at Oxford and at Drayton House in Lowick, Northamptonshire, England, a palatial 14th-century estate that functioned as the titular Saltburn. The camera language the filmmakers developed was, like the film’s themes, one of juxtapositions that often verged on extremes. “We really told the story in single, big wide shots, or by cutting into tight close-ups, where we’d often go really tight,” Sandgren says.

The filmmakers used close shots of characters and objects to underscore themes of sexuality and desire. To capture Fennell’s vision of moments that were “ugly and sexy at the same time,” Sandgren notes, he shot “close to the skin so you could see sweat, armpits, body hair.” The director adds, “We needed to be able to see pores, skin texture, blood, fluids and sweat — not just artful, slithering sweat, but real, beading sweat. It’s a very visceral film. We wanted to be able to see taste buds on people’s tongues. We kept thinking [that] if you’re living in a very stylized, beautiful and artificial world, which is the world of the aristocracy — and I guess, the world of filmmaking, too — and you’re dealing with sex and desire, [then] what you crave are things that feel human inside those worlds.”

Watching From Afar

Throughout Saltburn, the viewer is often aligned with the characters’ voyeurism, through angles that peek through doors or observe others from a distance. “There’s a sense of ‘peeping’ throughout the film — of peeping inside something, opening a window and looking in,” says Fennell. “We used those motifs again and again — showing characters through windows and revealing people in mirrors, or behind or through things.” To create the voyeuristic experience, Sandgren relied upon wide shots as much as he did very tight close-ups. In one scene, for instance, as Felix makes out with a girl in his dorm room it’s slowly revealed that Oliver is watching menacingly from outside the window. “We track to them, and then between them, we see Oliver in the window, [and] we just see the little bit of fire from his cigarette,” Sandgren describes. “It’s kind of a ‘cowboy’ — not even a mid-shot, but a wider shot. Emerald loved those wider compositions where you can see the whole environment.”

“Emerald wanted it to feel like we were looking into a dollhouse or an old-school TV and watching the characters inside.”

Long tableau shots pervade the film. One of the most memorable finds Oliver lying atop a fresh grave on the Saltburn property. The shot begins as a moment of mourning, but slowly becomes something disturbing. “It’s just one really long shot that’s held for about three-and-a-half minutes,” Sandgren explains. “At first, it’s kind of beautiful to keep a distance and be respectful to the character and not go in too tight. You’re not in his eyeline, so theoretically you can keep standing and watching.” This approach, the cinematographer notes, helps drop audiences into a realistic vantage point from which one might actually observe such a scene: “Would an onlooker really be standing in the mid-shot? No, you wouldn’t.”

Camera, Format and Lenses

Sandgren filmed with the Panavision Panaflex Millennium XL2 in the Super 35 format, and notes that shooting the movie digitally was never a consideration. Fennell explains, “We wanted that added texture, and in post, we interfered as little as possible with the grain. We didn’t mind if there was a little hair or sparkle. Why shoot on film and then make it feel less [like] film?” Sandgren reports that he used Kodak Vision3 50D 5203 film negative for sunny exteriors, 250D 5207 for day interiors, 200T 5213 for misty days and 500T 5219 for nights.

Having tested a number of different aspect ratios during prep, Sandgren decided that the interior compositions he and Fennell were after ultimately warranted the use of a near-square format. They therefore made the atypical decision to capture Saltburn in 1.33:1. “Emerald wanted it to feel like we were looking into a dollhouse or an old-school TV and watching the characters inside,” Sandgren says.

The rooms in the Saltburn estate are themselves square and tall, so shooting 1.33:1 facilitated fuller views inside. Says Fennell, “In a house like that, the ceilings are frescoed, the floor has marquetry detail, every light switch is ornate … there would be so much we’d be missing if we used an aspect ratio that cut those off.” Sandgren notes that their motivations were also art-historical: “On the walls of the Saltburn estate are portraits of ancestors going back hundreds of years that are composed in formal framings. So, for me, it made sense that these characters should be portrayed in the same way. We quickly realized that if we shot in a square format, the close-ups would be very singular and portrait-like.”

Sandgren shot Saltburn with Panavision’s Primo spherical lenses. He had worked with them previously on The Nutcracker and the Four Realms, and loved the overall effect they gave. “We tested many lenses, but I went with the Primos because I remembered the richness I felt they brought to Nutcracker,” he notes. The cinematographer describes the Primos as “sharp, but more contrasty. They have more depth, a sort of mushiness, or thickness.” He also likes the lens flares they create: “They have these red circles that are really beautiful.”

Lighting the Property

Saltburn’s lighting strategy is also one of contrasts, ranging from very natural and minimal to theatrical and bold. The vast majority of the scenes in which Oliver, Felix and members of Felix’s family lounge around Saltburn’s extensive grounds during the day were shot with natural light only. “We wanted the exterior summer days to feel really hot and romantic, and to provide contrast with the nights, which had a haunted vibe,” Sandgren says. “The visual arc of the film climaxes in a sort of vampire-esque tone, where silent horror films served as inspiration. Throughout the film, gaffer Ian Sinfield and I experimented with different techniques to light the scenes in an expressionistic way.”

In some instances, only practicals were necessary. For a large-scale dinner-party scene set in a dining room, where the Catton family’s guests are seated across a lengthy table, Sandgren primarily used candlelight for illumination. The flickering candles, fitted in candelabras and votives, give the scene an elegant, yet disquieting chiaroscuro effect, with darkness shrouding the edges of the frame. After dinner, the party retires to a room of sofas for karaoke. Here again, Sandgren opted for a minimalist approach — mostly using the dim glow of a flat-screen TV and a roaring fire in the room’s fireplace to light the scene. “The fire was incredibly big if you look at it, but the goal was to be expressive, like the Baroque painters,” Sandgren says. “We had to protect the fireplace properly so we could crank the propane flames up to the exposure we needed, but it really worked well.”

“One of the beauties of celluloid is that it can really take care of the shadows.”

In general, Sandgren wasn’t afraid of underexposing a bit. “I rated [each stock] 2/3 of a stop over to keep the shadows rich and the grain finer,” he says. “One of the beauties of celluloid is that it can really take care of the shadows.” Shooting on film, he opines, helps capture colors with more nuance. He also likes to stay away from completely clean color balance in regard to lighting, favoring more overt color contrast.

He cites a scene in the bathroom when Oliver is talking intimately with Felix’s sister, Venetia (Alison Oliver). “We used a warm key light to create a warm atmosphere, but without a cooler fill it would have looked really monochrome,” he notes. “Having a very warm light [with] a really cold light as a fill helps the perception of depth and color for the viewer, so you see both their eyes and skin tones. The whole image just somehow looks rich and white-balanced, even though it’s full of color.”

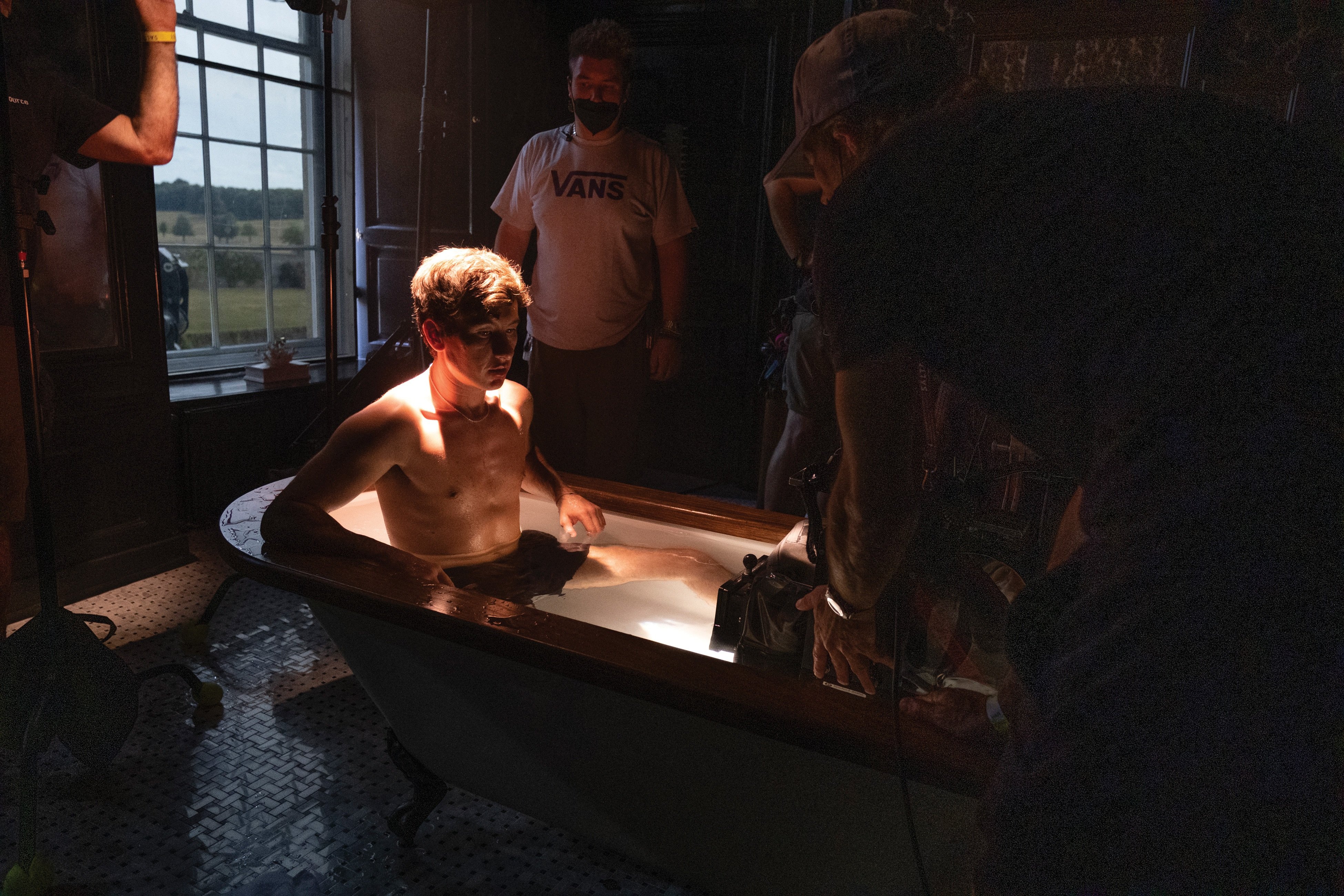

While staying at Saltburn, Oliver shares a bathroom with Felix, and it becomes the site of much intrigue. In one scene, Oliver, peeping through a crack in his bedroom door, watches Felix in the tub. The latter is bathed in golden light, his skin reflective and wet. Sandgren notes that this lighting was intended, in part, to affect a heightened reality. From a practical standpoint, the setup insinuates that there’s a warm light installed above the bath, but it also suggests that, from Oliver’s point of view, Felix is an object of desire who’s in a spotlight of sorts.

“With this method, we got a more stylized night-interior look.”

“We had a PAR can with a super-spot lens over the bathtub, because those fixtures give a really nice, hot projection,” Sandgren recalls. “We lit him quite hard to evoke a sensuality, with his skin shiny and his face, hair and neck visibly covered in sweat. Felix’s skin popped brightly and [the light] bounced off his body, to illuminate Oliver’s face as he’s secretly watching Felix from a crack in a doorway.”

Sandgren shot the scene day-for-night on 5219 stock — periodically applying ND 2.4 gels to the windows, with M90 HMIs serving as moonlight that shined through them. These insert hard gels reduced the intensity of the incoming light, which, as seen by the tungsten-balanced film stock, became a deep blue. “With this method,” he says, “we got a more stylized night-interior look, which we appreciated, but it also gave us the opportunity to plan scenes in any order, by shooting most interiors in daytime.” Sandgren then placed Vortex LEDs in the bathroom to add some blue fill and red light.

A Lonely Dance

For many of the shots of Oliver at Oxford, the filmmakers wanted to pointedly portray the character as lonely and isolated. “We created a lot of obstacles for him,” Sandgren describes. “We would show him behind fences or behind glass with bars in it. There’s a scene where he’s in his room at school and there’s a window between him and Felix’s group of friends — it almost looks like he’s in a prison.”

The barriers between Oliver and what he desires steadily dissipate throughout the film. This culminates in the final scene, when these obstacles have disappeared completely, and he dances through the rooms of Saltburn fully naked. Filming the dramatic dance, which traverses a number of rooms in the mansion, was uniquely tricky. “Obviously, we had to light every room,” Fennell says, “but we couldn’t have any of the rigging visible, so everything had to be carefully hidden.” Getting the timing right was difficult as well, especially because the dance was choreographed but meant to feel off-the-cuff. “We had to make sure we weren’t moving too fast for the music, and though we could rehearse it, we couldn’t really rehearse [with the actor] naked,” Sandgren says. Fennell adds that it was essential to give Keoghan room in order for the routine to look natural. “It’s like the dance that everyone [does] alone around the house … it was all about keeping that perfect distance with the camera,” the director says.

Working with a skeleton crew, the filmmakers shot the scene as a oner without sound, using Steadicam. Ossie McLean — one of Sandgren’s collaborators on the James Bond film No Time to Die (AC April ’20) — operated the camera. It was one of the film’s few uses of Steadicam. (“We used it for ‘walking-through-the-castle’ kind of shots, but otherwise, we mainly used dolly,” the cinematographer notes.) Getting the shot took careful orchestration and a number of tries. “At around the seventh or eighth take, we got it technically perfect, but the shot was still lacking some of the messy joy we wanted,” Fennell says.

The filmmakers kept going until they felt they achieved that little touch of imperfection and ugliness they were after throughout the film — which happened around take 11. “When we got it, it was an incredible relief, because this scene needed to feel really good,” Sandgren says. “It symbolizes Oliver’s character. Here, we see that he needs no one else. He’s just on his own, enjoying his obsession.”

The director and cinematographer were later interviewed by Michael Goi, ASC, ISC for this episode of ASC Clubhouse Conversations: