Rehired Gun: No Time to Die

Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF shoots 007 for director Cary Joji Fukunaga.

Unit photography by Nicola Dove, SMPSP. Additional images by Jack Mealing, courtesy of Danjaq, LLC AND MGM.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the April 2020 edition of AC and is re-presented here to coincide with the film’s theatrical release, which was postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Just when he thought he was out, they pulled him back in. As No Time to Die opens, James Bond, Agent 007 (Daniel Craig), is soaking up the sun. Following events depicted in Spectre (shot by Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC; AC Nov. ‘15), the superspy has retired from British intelligence and settled in Jamaica for some much-needed recuperation. It seems like an idyllic epilogue to a career marked by violence and tragedy, but another chapter begins when a CIA pal, Felix Leiter (Jeffrey Wright), pays a visit and recruits him to rescue a kidnapped scientist. Unexpected perils mount as the mission leads Bond to a mysterious villain (Rami Malek) armed with dangerous new technology.

This 25th Bond extravaganza was directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga, the series’ first American helmer, and shot by Oscar-winning cinematographer Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF. Fukunaga reached out to Sandgren shortly after boarding the project. “I’d seen a few of Linus’ films, but it was his visceral work on First Man [AC Nov. ‘18] that made me think he’d be perfect for Bond,” Fukunaga says. “I liked how he pulled off a mixture of highly technical cinematography and simple but elegant lighting approaches to night exteriors and interiors.”

“In that first discussion with Cary, I realized we have a similar attitude toward filmmaking,” says Sandgren, speaking to AC from EFilm in Hollywood, where he is grading No Time to Die with supervising digital colorist Matt Wallach. “Watching Cary’s work, from [features] Sin Nombre, Beasts of No Nation and Jane Eyre [AC April ‘11] to [TV series] True Detective and Maniac, you see a confident filmmaker who isn’t afraid of anything. He takes projects as far as he possibly can, and I love that. He wanted Bond 25 to be an epic cinematic journey, both adventurous and emotional, that would make audiences close their eyes in fear, laugh and cry. To me, that is exactly what a Bond movie should be. And based on Cary’s previous projects, I felt he was going to go all the way and [take the franchise] in an exciting direction.”

Sandgren was invited to London, where he met with Fukunaga and producers Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli, who welcomed him onto the project. “I was very excited for the opportunity,” says the cinematographer. “Bond was definitely a different challenge from my other projects. The Bond films inspired me as a teen to make shorts on Super 8 film and eventually become a cinematographer.”

While recent Bond movies could be characterized as somber and gritty, Sandgren notes that he appreciated Fukunaga’s desire to steer No Time to Die toward raw, intimate storytelling, while being “faithful to the heart of the Bond genre.” The team would ultimately incorporate the kind of grand, global escapade — or “classic romantic adventure,” the cinematographer says — as seen in the franchise’s earlier chapters while telling a human tale. “We love the old Bond movies, and we all worked in that vein, but this was also going to be, as Cary emphasized, an emotional story, which gave us a wide range of human feeling to work with. We have a lot of very physical, realistic action, but it’s not cynical — it’s exciting. The story is also full of humor. To me, the cinematography of a film is like the music in a film; it’s there to express a feeling, and ideally, you should be able to understand the emotions from just the images. And the more emotional layers a film has, the more expressive you can be.”

Still photographs and mood boards were a chief way that Fukunaga, Sandgren, gaffer David Sinfield and production designer Mark Tildesley shared ideas. “We worked to create great variety in the lighting and the colors of scenes to create a palette that was as rich as possible,” says Sandgren. “I also always try to find metaphorical inspiration for the lighting from the various themes in the story or from the characters themselves.”

But Fukunaga also sought consistency. “The bigger questions were around how to give each of the film’s expansive locations a unique look while making it feel like the same film,” Fukunaga says. “It was about finding that balance.” The filmmakers certainly wanted to emphasize the contrast between the warmth of Jamaica and Italy, and the cold, nearly monochromatic feel of Norway and of such institutional interiors as the chamber where former Spectre head Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Christoph Waltz) speaks with Bond.

The production was captured on a combination of 35mm and 65mm film negative. The filmmakers wanted smooth transitions between the two gauges, so entire sequences were designed for one format or the other, with no intercutting. The extended pre-credit sequence (shot in Norway), in which Safin hunts down victims on a frozen lake, will play in Imax in theaters that are so equipped, and then the first scene following the credits is anamorphic widescreen. Other Imax sequences include a car chase in ancient Matera, Italy, and an action scene in Cuba involving Bond and Nomi (Lashana Lynch) — a fellow double-0 agent with elite skills, who’s promised to give the super spy a run for his money.

The production was shot mainly on Kodak Vision3 500T 5219, though Vision3 250D 5207 and 50D 5203 were employed as well, the latter specifically for 35mm-captured day exteriors. The crew shot 1,007 rolls of 35mm — and more than 1.7 million feet of 35mm and 65mm total.

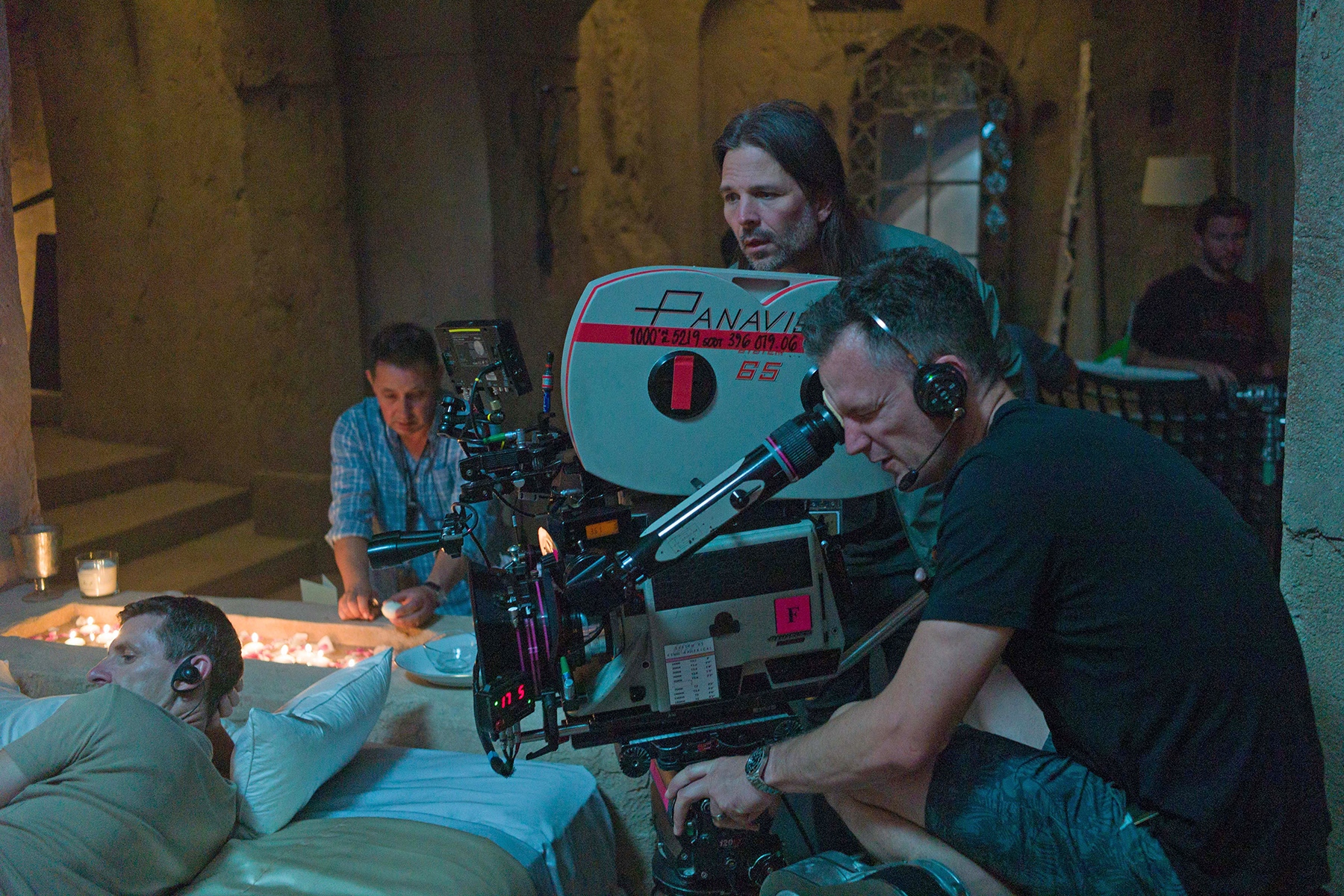

The majority of the picture was captured in anamorphic 35mm — which Sandgren regards as “the classic Bond format” — with Panavision’s Panaflex Millennium XL2.

Scenic action sequences, though, were captured in large format. “Five-perf and 15-perf 65mm look spectacular projected,” says Fukunaga, recalling the filmmakers’ initial large-format tests. “Some of the images just leapt off the screen.” The filmmakers used Imax MSM 9802 and Mark IV cameras for these scenes, with System 65 units employed for intimate dialogue because, says Sandgren, “Imax cameras are just a bit too loud.” When the System 65 units were unavailable toward the end of production, the filmmakers turned to the 65mm Arriflex 765 — which was more often used by the production’s 2nd unit for dialogue within Imax sequences.

When shooting Imax, the camera team framed for both 1.43:1 and 1.9:1 — owing to differences in Imax venues’ projection systems. Five-perf was usually tiled for 1.43:1, according to Sandgren. “Framing for 1.43 while protecting for 2:40 is not as challenging as you might think,” Sandgren notes. “It can be a lot of work to make sure the sets are covered in all formats, but regarding the composition, the 2:40:1 aspect ratio in the center of the image will still be where your eyes are looking when the movie is projected in Imax. The additional top and bottom of the Imax frame is really the periphery; it’s used for atmosphere and to [further] immerse the audience in the movie.

“The story required us to use Imax cameras in very challenging conditions,” he adds, “including temperatures below zero, in air, on cables, underwater, and in heavy-action vehicle stunts, and the cameras really performed [beyond] our expectations.”

Imax supplied the Hasselblad lenses for its cameras, and Dan Sasaki, Panavision’s senior vice president of optical engineering and an ASC associate member, developed custom high-speed close-focus Panavision lenses with an Imax mount for 15-perf in 40mm (T2.6), 50mm (T2), 80mm (T1.9) and 300mm (T4) focal lengths, as well as a 460-1,430mm (T8) zoom. The Imax Hasselblad lenses were 40mm (T4), 50mm (T2.8), 60mm (T3.5), 80mm (T2), 110mm (T2), 150mm (T2.8) and 350mm (T4). Panavision Sphero 65 lenses were paired with the Panaflex System 65.

After much testing, Sandgren chose Panavision G Series Anamorphic Primes for the Panaflex Millennium XL2 — a strategy inspired by E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (shot by Allen Daviau, ASC). “I was looking to re-create the red-circle lens flares Allen got on those beautiful old spherical lenses,” says Sandgren. “I wanted a lens that would be a workhorse but also have beautiful flares that weren’t overly dramatic. I have mostly used the C Series, which I love and which have a lot of attitude, and the Primo Anamorphic Primes, which were nearly perfect for us but too heavy. I wanted lenses with a sharp look that are lightweight and fast, with interesting impressionistic characteristics.

Dan Sasaki helped us experiment to find the E.T. look by modifying the T Series with built-in IR filters and various coatings, which looked quite interesting but still wasn’t exactly what I was looking for.”

Sandgren even reached out to Steven Shaw, ASC, E.T.’s 1st AC, who recalled shooting with an uncoated Panavision spherical lens.

It was 1st AC Jorge Sánchez who suggested using the G Series. “We shot some tests, and wow, how they performed!” says Sandgren. “They’re fast and sharp, and I learned to love them more than the Cs. They’re beautiful and gentle but with lively, soft flares.”

For his part, Fukunaga says, “I love Panavision anamorphics. I’d had more experience with the C and E series, so I was interested to see how the G Series performed in the variety of dark and light sets we had.”

Go-to focal lengths were 80mm for the Imax cameras, 50mm for the System 65, and 40mm for the XL2. Referring to the latter, Sandgren notes, “A 40mm lens is probably most true to reality when it comes to how the depth in the space falls off. When shooting spherical 35mm, I often find a 40mm too tight to see the width of a set, but with anamorphic, it accommodates for that and also enables you to move in for a close-up.”

He also shot interiors at T2.8 on both camera formats, stopping down to T5.6 or T8 for day exteriors. “The G Series performs so well at T2.8, whereas other anamorphic lenses might not,” Sandgren observes. “I like it when practical lights such as neon signs, car headlights and fluorescent tubes expose naturalistically, and I find T2.8 provides the most appropriate exposure on 5219.”

Sandgren worked with Tildesley and Sinfield to integrate practical lights representative of the respective locales. “Linus and Dave would ‘audition’ different color-temperature combinations and show them to me,” Fukunaga says. “From there, we started to find a palette we consistently gravitated toward. It was as if the film itself was dictating the color, and Linus and I were just homing in on it as we went forward.”

Having scenes in Jamaica and Cuba, where Bond crosses paths with Nomi, required visually differentiating the neighboring islands. Sandgren explains, “Jamaica is romantic in the film — Bond’s retirement home is on the water, situated next to an exotic, rural city. Santiago de Cuba, meanwhile, is an old city full of history that hasn’t changed much in 50 years. ”

The production shot scenes set in both locales in Jamaica, with Port Antonio in Portland Parish standing in for parts of Cuba. In addition, Tildesley, who scouted the latter, spearheaded the building of a Santiago de Cuba street on the Pinewood Studios backlot for the Imax night sequence in which Nomi, on a mission, causes an explosion that lights up the neoclassical buildings.

“In Cuba, you often see neon and harsh fluorescent lighting in some of the bars,” Tildesley notes. Sandgren worked closely with Tildesley’s art department and set decorator Véronique Melery to figure out appropriate practical sources with interesting color combinations for each scene. The cinematographer recalls, “We actually manufactured many practical lights ourselves that were creatively integrated into sets — for example, a shimmering wall, and fluorescent-looking fixtures that could work underwater.”

The Cuba sequence required A-camera/Steadicam operator Jason Ewart and B-camera/Steadicam operator, Ossie McLean, to handhold the Imax cameras. “Those cameras are a lot heavier and quite awkward to operate,” Ewart says. “They weren’t designed for action sequences. We did quite a lot of handheld with them, which was challenging, to say the least. Their size and weight took a lot of getting used to, and it was physically demanding to follow these fast-paced fight and action scenes.”

Camera moves called for varying degrees of planning, Fukunaga says. “Some moves were thought about ahead of time,” he adds, “certainly for action scenes and scenes that needed previs, but for the most part, the actors, Linus and I would [map] out the camera positions once the blocking had been set.”

“Sometimes a simple, intimate, handheld shot was much better than a dramatic crane shot,” Sandgren adds. “The range in this film is as wide as it can be!” One notable crane shot featured in a scene where Bond, showing up at a Spectre party in a dark ballroom, is revealed by a spotlight to be surrounded by unfriendly figures. The first portion of the scene was covered on Steadicam and dolly as Bond moves about, and then a high-angle setup revealed the sea of opposition he faces.

Sandgren describes the desired tone of this sequence as “sinister menace and claustrophobic paranoia, a bit in the spirit of Hitchcock.” The lighting reflects that mood with 2.5K HMI Ivanhoe spotlights washing across the faces of Bond and CIA agent Paloma (Ana de Armas), adding to the drama. The crew used 5K Fresnels dimmed to 40 percent, motivated by the room’s tungsten practicals, along with an array of Arri SkyPanels — S60s in lightboxes rigged on electric motors from the roof, S360s with Chimeras, and S60s bouncing off bleached muslin on the floor to provide fill.

“My lighting crew was dressed by [Suttirat Anne Larlarb’s] costume department to operate the spotlights on camera,” Sinfield recalls. “We had many cues for interactive lighting from our various sources built by desk operator Adam Baker with the GrandMA2 console, and I controlled them via iPad or iPod Touch.” This manual operation allowed him to organically respond to the action as opposed to relying on pre-set timings.

The special-effects team added an atmospheric effect that figures into the story. “It worked great with our lighting concept,” the gaffer says. “Linus and I worked together and added new ideas to every scene. Collaborating with him is a never-ending journey; his ideas make you think on your feet, but they are fantastic, and he is open to your input.”

“David Sinfield is a brilliant gaffer — full of creative ideas, always positive, and exceptionally prepared and competent,” says Sandgren. “He runs an amazing crew — [and] at one point during production he had more than 1,000 SkyPanels rigged in overhead lightboxes, eight 100K SoftSuns, and a 200K SoftSun rigged on different soundstages at Pinewood.”

The main unit usually ran one camera, but seated-dialogue scenes were covered by two. (The B camera was initially operated by Oliver Loncraine, but when he left to serve as cinematographer on another project, Ossie McLean stepped in.) “Cary likes to tell the story efficiently, with as few cuts as possible,” Sandgren notes. “Also, we both love a curious camera. We often worked out blockings where the camera is almost its own character, observing the intimacy of the characters as it explores the scope of the sets. That could include a 360-degree turn, so mostly we shot in single-camera style, having the second camera leapfrog to the next setup.” On heavy action sequences, however, the crew ran up to five cameras.

The production’s 2nd unit — led by director-cinematographer Alexander Witt, ASC, ACC — was just as big as the main unit, and logistics prevented them from occupying the same location at the same time. In the case of the Matera car chase, Witt’s team traveled to Italy first to shoot the wider vehicle stunts, including helicopter footage, before the 1st unit came in to shoot the majority of the scenes, including vehicle stunts with Craig and Léa Seydoux (playing Madeleine Swann).

The stunt cars in the film were all built or modified by special effects and action-vehicle supervisor Chris Corbould and his team. “They built eight stunt DB5s with roll cages,” says Sandgren. “The bodies were custom-built by Aston Martin in carbon fiber, and the chassis had been fitted with fixed pick points to hold camera rigs. Thanks to Corbould’s team and to the innovative mind of my key grip, David Appleby, we were able to quickly mount the heavy Imax cameras anywhere on the car. We also had custom rigs on motorcycles that could handle Imax cameras affixed to their front and rear.”

In the sequence, Bond drives the armed Aston Martin DB5 introduced in the 1964 installment, Goldfinger. As Bond and Swann are pursued through the narrow streets by an enemy motorcycle and sedan, 007 accuses Swann of betraying him. Craig did as much of his own driving as was determined to be safe; otherwise, the stunt team had a driver in a pod atop the car steering the vehicle.

“Daniel is a very good driver and could do stunts on his own,” says Olivier Schneider, supervising stunt coordinator. “He spent time with [stunt coordinator] Lee Morrison rehearsing parts of the chase. He had to manage the presence of the camera while focusing on his lines and his acting, as well as safety. It was a lot of pressure.”

A few tighter car interiors throughout the film were shot at Pinewood on an LED stage provided by Creative Technology Group. “We set up a virtual world at Pinewood,” Sandgren says, “where we built a 3⁄4 fixed cylinder of LED Black Pearl screens from CT Group, with a pixel pitch of 2.8mm. The cylinder diameter was 30 feet, and there was a movable screen covering the top. This was the same type of concept we used on First Man.”

The car was surrounded by screens projecting moving-background footage that had been taken on location by a vehicle rigged with eight digital cameras capturing various angles from Bond’s point of view. “That way the car was covered with realistic lighting and reflections, and we would just add some ambiance with SkyPanels and sunlight from a Mole Richardson 5K PAR on a [Chapman/Leonard] Hydrascope crane,” Sandgren says.

A climactic moment in Matera has Bond grabbing a motorcycle, riding up a steep facade protruding from an ancient wall, and launching himself onto a street level above, where he drops 12' and lands as a procession leaves a nearby church. Morrison oversaw the carefully rehearsed stunt, which was performed by Paul Edmondson and shot by the 2nd unit in four takes.

Such scenes were designed during prep, which stretched from November 2018 until the 122 days of principal photography began the following March. “Linus would always share ideas with you to see what you could bring,” Schneider says. Throughout the shoot, Sandgren and Sinfield communicated daily with Witt and 2nd-unit gaffer Toby Tyler Jr. to ensure consistency in all footage.

Perhaps the biggest-scale nod to the franchise’s storied past is a gigantic underground set. The set might bring to mind production designer Ken Adam’s creation of Blofeld’s base inside a volcano in You Only Live Twice (shot by Freddie Young, BSC) and Spectre’s colorful garb in that film. Tildesley and his team built the set in the massive tank at Pinewood’s 007 Stage.

“We had Ken’s book [Ken Adam: The Art of Production Design] firmly opened on our desk throughout the whole process,” Tildesley says. “As this is Daniel’s last film in the franchise and the 25th Bond film, we thought hard about how to evoke some of the best bits and pieces from the previous films.”

sticks.

Dozens of tall light sticks standing in the water both serve the plot and provide ambiance in the cavernous set. “I asked my practical team to find some 4-inch-diameter tubes between 6 and 8 feet tall that we could use as light sticks in the water to replicate Mark Tildesley’s design,” Sinfield explains. “After lots of R&D, I decided on a design, and Cary, Linus and Mark all liked it. We ended up making about 50 6-foot-tall, freestanding light sticks filled with 5 meters of LiteGear LiteRibbon that we controlled from the lighting desk via wireless DMX. They gave an amazing amount of soft light that we could easily control.”

Sandgren adds, “I thought the concept art of this set was really exciting and I was intrigued to try to light the entire massive set with these 50-something light sticks. At the end of the set there was also an elevated lab, which was a bright source of light, featuring a transparent wall illuminated by 40 8-foot-by-2-foot LiteGear LiteTiles [placed behind it]. In the ceiling of the set, we had made a 20-foot circle with functioning doors that would [ostensibly open to the above-ground surface], and it had to be lit to produce daylight washing down as the doors opened. Tildesley had designed the set to its maximum, and it barely fit into the 007 Stage at Pinewood — giving us about 5 feet of space to fit lights above the circle. We arranged four 100,000-watt SoftSuns above the circle that we shot inward to bounce off an Ultrabounce. The SoftSuns are fully dimmable, so we brought the 400,000 watts worth of light up as the doors opened, creating the effect that bright daylight was spilling down into the set. We shot this at T2.8 on 500T.”

Working on a Bond film, and in particular, this landmark entry, inspired the entire crew to give their best. That sense of teamwork suffused the production, and Fukunaga certainly felt it with Sandgren. “Linus is one of the most supportive collaborators you could find,” the director says. “Inevitably, time and budget constraints weigh down on creative choices, and when I was at the point of bending to compromise, Linus would stand up with his persuasive smile and his laser focus on the end result, and say, ‘Well, you could do it the right way or you could do it the wrong way.’”

The cinematographer later discussed his work in the picture as part of our ASC Clubhouse Conversations series, interviewed by Natasha Braier, ASC, ADF: