Scarface: Noir No More

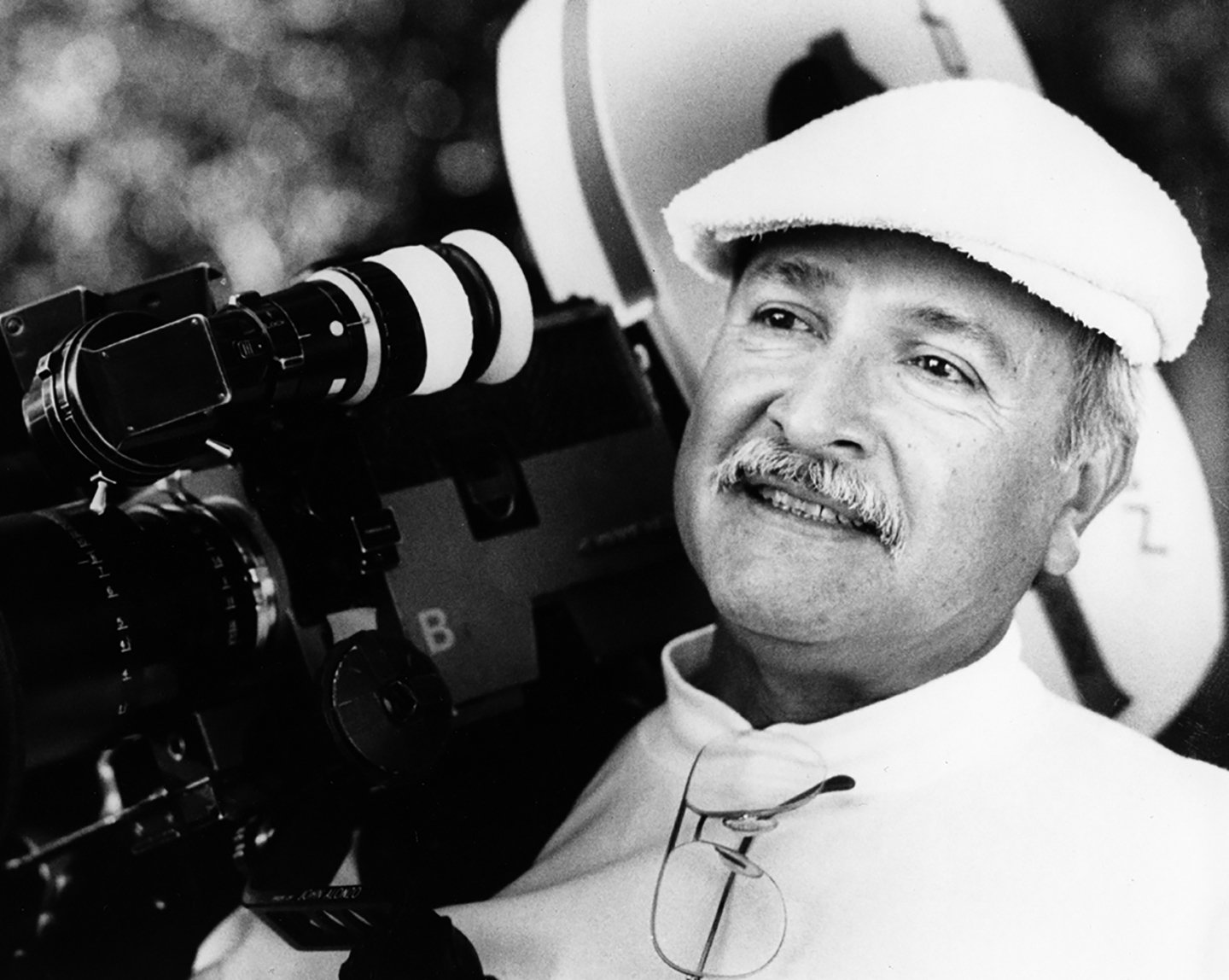

John A. Alonzo, ASC talks about re-teaming with director Brian De Palma for this crime epic, and details Pacino's professionalism.

This article originally appeared in AC Dec. 1983.

Scarface is more than a remake and update of a 50-year-old classic, with cocaine substituted for rumrunning to give it a contemporary theme. On other levels, it is the story of a man who cannot accommodate new wealth — no matter its source — a man who is overwhelmed by his creation.

Visually, the film is a study of contrasts — from the seedy life of the new immigrant to the extravagant opulence of the drug dealer. This is in no small way due to the work of John A. Alonzo, ASC, the director of photography. Alonzo, whose previous work includes this year’s Blue Thunder and Cross Creek, as well as such films as Chinatown, Norma Rae, Lady Sings The Blues, Harold and Maude and Sounder is a cinematographer who resists being typed.

“In the past,” he says, “because cinematographers were under contract to the studios, because directors were under contract to the studios, they would be pigeonholed: ‘This guy does comedy; this cinematographer is good with this director,’ things like that.” As a freelance artist, Alonzo has never accepted an assignment that repeats something he’s done before. “Some people say that’s not entirely true, that Farewell My Lovely is like Chinatown, but I think they were completely different in style, lighting, use of lenses and color.”

“When I first read a script, I get thoroughly involved in the material; I read it for the story content. Then I re-read the material with the director in mind. It’s his concept that determines the look of the picture.”

— John A. Alonzo, ASC

Scarface marks the second time Alonzo has worked with director Brian De Palma, having been director of photography on De Palma’s first Hollywood film, Get To Know Your Rabbit. When asked about the criticism of De Palma as a derivative director who consciously styles his films on the work of others, Alonzo replies, “I don’t think that’s a correct observation of his work. Perhaps because he isn’t a very flamboyant person, or someone who is very visible, the writers can’t put their fingers on it and say, ‘This is who this guy is.’ ”

De Palma has been quoted regarding Scarface that when he read the script, he saw in it the character study he had been looking for as a vehicle for his special visual imagery. Alonzo recalls his first meeting with De Palma to discuss the project thus: “Succinctly, he told me, ‘Look, if it reads dark, it reads film noir; it’s going to be that way. We’re going to contradict it, and let the action happen within the frame. If a violent act is going to occur, the surroundings should be bright, not dark.’ ” According to Alonzo, this was not done for any trick, but to introduce the Latin style, which is bright and colorful. “That was a big image for me,” he relates. “I immediately started thinking that if there’s a murder, if a gun fires, there should be bright lights with great color in the background. That comment by De Palma gave me a direction.”

Alonzo has very definite ideas about the relationship of the director and cinematographer. Telling how he comes to a sense of the visual dimension of a story, he says, “When I first read a script, I get thoroughly involved in the material; I read it for the story content. Then I re-read the material with the director in mind. It’s his concept that determines the look of the picture.” That may be a very different philosophy from other cinematographers, but as he states, “The director is the one who is responsible. They give me a canvas and I paint on it.”

Alonzo also has very definite ideas about the new importance accorded the visual aspect of film. “I think that today, the young, new directors are very aware of the importance of the visual aspect of film. Cinematographers have to be aware that if the visual aspect is calling attention to itself too much, it can be a distraction. As Martin Ritt says, ‘Technology, artistry and style must support and accommodate the story, not the other way around.’ The visuals can take hold too much and take the audience off on a tangent. When that happens, the cinematographer has not done his job.”

The story of Scarface, with its subtle nuances of characterization and storytelling, demanded thorough preparation on the part of all concerned. As Alonzo recalls, “Brian was very articulate about every aspect of the picture. Scarface is a very complicated piece, from a dramatic point of view. Many meetings were held with all department heads to insure that we were all going in the same direction with the film. The value of those meetings were best illustrated in the care and handling of the special effects. There are a tremendous amount of them in Scarface, and they were executed safely and flawlessly, at the same time maintaining authenticity and realism. Brian made certain everyone understood how violent an act would be and for what purpose, what reason.”

In developing a visual style for the film, Alonzo and visual consultant Ferdinando Scarfiotti looked at making things “bigger than life.” As Alonzo sees it;

“It is a story of overwhelming amounts of money, crime and violence. In other words, everything in Tony Montana’s way of life was exaggerated, and that was the visual key to Scarface.”

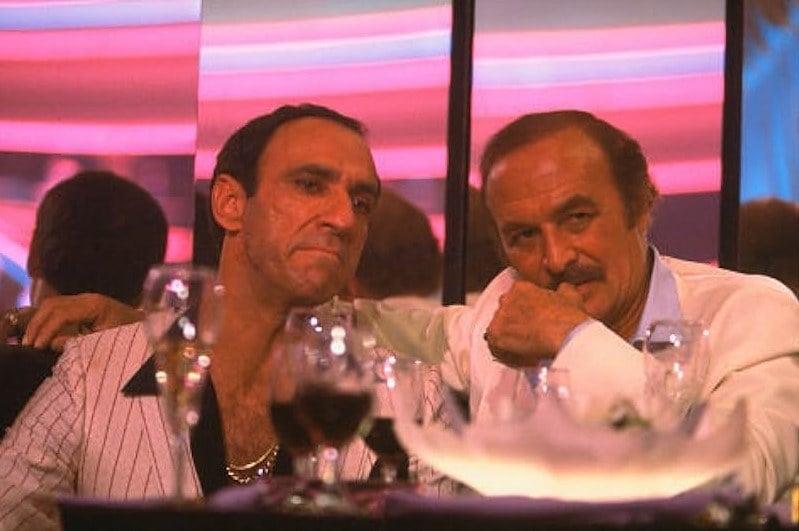

Perhaps the most flamboyant set designed by Scarfiotti — and the one that initially created one of the most difficult shooting problems for Alonzo — was the “Babylon Club.” Scarfiotti designed a circular building, with the set ringed by eight-inch by six-foot mirrors. According to Alonzo, his first reaction upon seeing this way to say, “Oh, my God! Where am I going to put the cameras? I’ll be seeing myself!” However, Scarfiotti had designed the mirrors with gimbals, so they could be turned and twisted. The set allowed Alonzo to give the picture another dimension.

As he recalls: “I could set the mirrors so you could see five reflections of Al Pacino, and simultaneously see him in the foreground, or hold him in the foreground and introduce reflections of other actors in the background. This introduced reflections of the characters in the story. Sometimes an actor would sit in one of the booths, and not even the back of his head would be reflected. On purpose, we would reflect dancers or extras walking around the club, as if to say, ‘There’s nobody here.’ ” Doing all this while using up to three cameras all pointing in the same direction, and each one avoiding seeing the other, became a challenge for Alonzo. “I’d have been in real trouble if I hadn’t figured it out!”

For the major action scenes in the film, the shootouts in the Babylon Club and the final showdown in Tony Montana’s mansion, Alonzo used multiple cameras to get the different camera angles needed by Director De Palma so the scenes could be shot in one take. According to Alonzo, arming the actors with the necessary squibs was a three or four hour job for the effects men, and time is money. “This way, when we reloaded, set up again, using multiple cameras allowed us to get the equivalent of six or seven takes with only two setups.”

One very valuable piece of equipment used in these scenes was the gun-synchronizer invented by effects men Ken Pepiot and Stan Parks. According to Alonzo, “It has always been a problem when you’re shooting 24 frames and someone is shooting a gun. You may or may not catch the flash. The only way you know is, if the operator didn’t see the flash, the camera did. The synchronizer prevents the gun from firing unless the camera shutter is open. It’s a little cumbersome, because now the actor has another wire coming down his leg, and he can’t necessarily fire as fast as he’d like to. It becomes something of a technical problem for the actor, because he has to perform and act in sync with the weapon. For those shots where it was essential to get the flash, to see the gun fire, it was invaluable!” Alonzo believes that use of the synchronizer will allow substantial savings in post-production costs, since the gun flashes will not have to be rotoscoped in. “It costs a fortune to rotoscope! I think they have created a piece of hardware that we can use very well. They deserve an award for it.”

Another technical achievement in the film was Alonzo’s use of the Panacam video camera to get the “surveillance camera” shots used in the various video monitors in the mansion. According to Alonzo, “If you really used surveillance cameras, the quality would be very poor, you wouldn’t have the frame be the exact size you wanted. By using motion picture lenses on the Panacam, using longer lenses, tighter lenses, we could cheat ourselves into a real close-up shot that would look like the surveillance camera had just zoomed in automatically. The toughest thing was for the operator to work it ‘mechanically.’ The tendency for a camera operator is to operate a shot perfectly, with motion and smoothness. Here, they had to respond like a robot, they had to be robots. It was fun: I’m sure the guy operating the camera was saying to himself, ‘Wait a minute! It’s against my nature to do that!’ ”

Other sets presented other photographic difficulties. Alonzo remembers a real “stretch” happened in shooting at the mansion in Santa Barbara. “It had enormous windows! It was a private home, we couldn’t put nails in the wall, install shades. That became a problem because there are seven or eight characters in that scene, in front of the enormous windows. I couldn’t shoot it as an interior scene it had to be done as an exterior. The light would change from high to low, and we had to make it look all the same. That was where the [Eastman] high-speed 5273 film came in very handy. When the light was low outside, we could continue to shoot and make those windows look as bright as they did earlier in the day.”

To Alonzo, the biggest “stretch” photographically was shooting in the office set designed by Scarfiotti. “I called it ‘The Black Office’ — black on black in black! I found I had to pour a tremendous amount of light there, just to get an image! I had to disregard the meters! I had 1,000 foot-candles thrown on the wall, and the meter would say it’s overexposed, but I knew it wasn’t. I had to trust that it was going to be all right. I also had to keep actors away from the hotly-lit areas. ‘The Black Office’ was definitely the toughest set.”

Working with Pacino was one of Alonzo’s most pleasurable experiences during the production. “The word ‘professional’ is to me an overused term, but with Al Pacino, you can’t over-use it.”

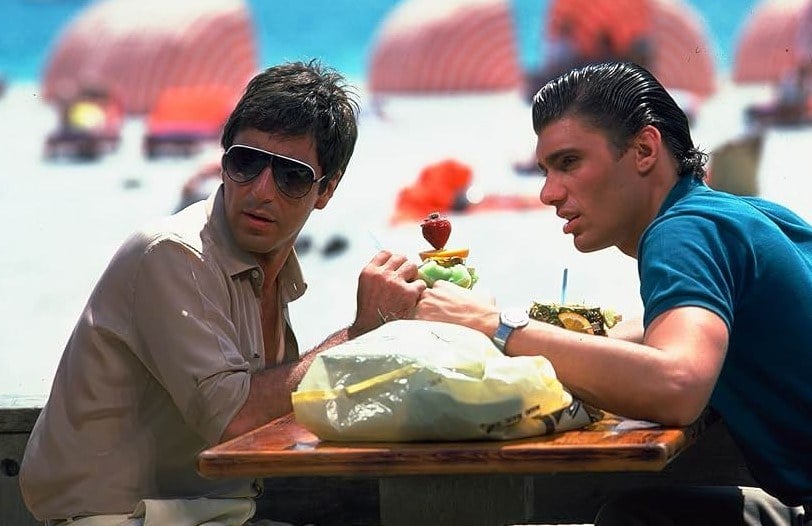

Pacino’s use of his Cuban accent at all times, both on and off-set, became legendary during the production. As Alonzo remembers, “When I first met him, we hadn’t even started production, and he was using the accent. I spoke Spanish to him and asked if it was okay. His response was ‘Please! The more Spanish I hear, the better I’ll feel.’ That, to me, is a prepared actor.”

Pacino’s method of working with the actors on the production also brings praise from Alonzo. “There was his relationship with Steven Bauer, who is going to be well-known as a result of the film. Al associated with Steven on- and off-set because they were supposed to be buddies in the picture. His relationship with other members of the cast with whom Tony Montana was supposed to be friendly was very warm. But actors playing roles whom Al wasn’t supposed to like in the story were kept at a distance. He was respectful to them, but stayed away from them, to maintain the performance.”

While Alonzo was working on postproduction of the film, he commented on his overall feeling regarding the film: “I saw the picture silently the other day, and it riveted me! To the point that I was distracted as I was timing it. For me, if a picture can do that with sound, it works. The choreography, the photography, the direction, the performances, all work. I knew what they were saying but I also wanted to hear it. I’ve worked on pictures where I have to wait until the effects are in, the dialogue’s in, the music’s in, to really make a judgment. Those are painful, because you’re saying, “Oh my god, it needs music! For me, it was a tough but rewarding experience. The film also makes a statement against drugs, which I think is important and timely.”